- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Gender and Migration in 21st Century Europe

About this book

Providing interdisciplinary and empirically grounded insights into the issues surrounding gender and migration into and within Europe, this work presents a comprehensive and critical overview of the historical, legal, policy and cultural framework underpinning different types of European migration. Analysing the impact of migration on women's careers, the impact of migration on family life and gender perspectives on forced migration, the authors also examine the consequences of EU enlargement for women's migration opportunities and practices, as well as the impact of new regulatory mechanisms at EU level in addressing issues of forced migration and cross-national family breakdown. Recent interdisciplinary research also offers a new insight into the issue of skilled migration and the gendering of previously male-dominated sectors of the labour market.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gender and Migration in 21st Century Europe by Samantha Currie, Helen Stalford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & International Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Gender, Migration and Managing Family Life

Chapter 1

The Effect of Family Migration on Union Dissolution in Britain

Paul J. Boyle, Thomas J. Cooke, Vernon Gayle and Clara H. Mulder

The negative influence of ‘family migration’1 on women has been well documented. Beginning in the 1970s, with work influenced by neoclassical economic perspectives, it was shown that women are less likely to be employed, earn lower wages and work shorter hours than otherwise equivalent women following long distance, intra-national moves with the family (Sandell 1977; Mincer 1978; Spitze 1984; Morrison and Lichter 1988). Explanations for this were derived from human capital theory, with the expectation that families move to improve overall household circumstances. Although a gender-neutral theory it was found consistently that women’s careers were less likely to benefit from such mobility while men tended to gain, with the expectation that such gains would offset the losses made by women in the medium- or even short-term. Hence, women were commonly referred to as ‘tied migrants’ or ‘trailing spouses’ in this literature.

In the 1990s and 2000s researchers have returned to this topic to explore whether, some decades later, women continue to ‘suffer’ from family migration. Given that women are now more likely to have higher qualifications, to be working, and to have career-focused jobs, it raises the question of whether they remain less likely to benefit from family moves. Perhaps surprisingly, the overwhelming consensus in the more recent literature is that women’s labour market position continues to suffer from family migration and this finding is consistent in a range of national contexts including the UK, the US and the Netherlands (Smits 1999; Boyle, Cooke et al. 2001). As a consequence, many have moved beyond relatively crude human capital approaches arguing for a more nuanced approach which recognizes the influence of gender roles and family resources (e.g. Shihadeh 1991; Bielby and Bielby 1992; Halfacree 1995; Jurges 1998; Bailey and Boyle 2004; Jurges 2006; Cooke 2008; Cooke 2009). For example, Boyle, Cooke et al. (1999) showed that women are more likely to be unemployed or economically inactive following long-distance family migration even in those cases when the women had a higher status occupation than their partner and these results do not appear to be explained by decisions related to child-bearing (Cooke 2001; Boyle, Cooke et al. 2003).

There has also been a growing recognition that longitudinal methods are required to tease out the complex relationship between life course events, mobility, and labour market outcomes. Panel data analysis comparing the UK and the US shows that the effects of moving as a couple on women’s wages appears to be nearly as great as that of giving birth (Cooke, Boyle et al. 2009) and certainly has a long-term impact. Longitudinal analysis also shows that the negative effects of family migration on women’s employment status are not purely a result of the selection of previously unemployed women into family migration (Boyle, Feng et al. 2009).

Overall, then, many of the results to date do not seem to accord with a simple gender-neutral human capital model and point to more deep-rooted gendered social structures as reflected in traditional gender roles. One consequence of such gender inequity within the family is that it could lead to tension between partners, raising the question of whether family migration may have an influence on couple separation. This was recognized as a possibility early on in the family migration literature. Mincer (1978) argued from an economic perspective that the ‘utility’ from remaining married can be affected by (im)mobility if individuals are forced into ‘tied migration’ or, alternatively, become ‘tied stayers’. If the personal loss to moving, or staying, exceeds the gains from marriage, then dissolution may occur and he did indeed show that marriage breakdown was more common in the 12 months bracketing a long distance move than in years that involved no migration (Mincer 1978: 769). Unfortunately, that approach did not distinguish between moves that stimulated separation and moves which were caused by separation. Here we explore this question using longitudinal panel data which allow us to sequence moving and separation events to get closer to a causal explanation of the relationship between moving and union dissolution.

Of course, the gendered labour market consequences of long distance moving may be only part of the explanation why moving may cause couples to separate. We also need to recognize that family mobility is a stressful event in its own right even when the move is over a short distance and the underlying reason for the move was not employment-focused (McCollum 1990). For example buying a first home and the subsequent relocation can be an extremely stressful event in the life cycle of a family. This is hypothesized to be particularly true since the media and popular culture characterize these events as joyful and relatively stress-free. Most families, therefore, are not prepared for the widespread disruption to their everyday rituals and lives (Meyer 1987: 198).

Indeed, the difficulties associated with moving are even reflected in websites designed to help with the moving process. From the minute the ‘For Sale’ board goes up outside your house, to the minute you put the key in the lock of your new home – moving house can be a stressful business. When the British public was questioned about which life event they found most stressful, moving home came top. A total of 44 per cent found it most stressful compared to 15 per cent who identified changing jobs as their most stressful experience, according to the survey in 2000 carried out for the health and disability insurance company Unum Ltd (Inman 2008).

The pressures associated with such mobility have even influenced recent government policy, with the British Government introducing a new system of house purchase in England, of which major aim of which being to reduce the stress associated with the moving process (Office of the Deputy Prime Minister 2004). ‘Sellers’ packs’ now have to be produced before a house is put on the market and include a survey, a draft contract and details of local authority searches. By making homeowners provide essential information up front, the government hopes to cut down on the time it takes to sell the property and reduce the likelihood of ‘gazumping’, where a buyer accepts a higher offer after already having agreed a price with an earlier buyer.

Of course, it is women who usually have to deal with much of the stress associated with moving as they are more likely to have to cope with the practicalities of the move (Weissman and Paykel 1972; Makowsky, Cook et al. 1988; Brett, Stroh et al. 1993). They are more likely to be relied upon to make the arrangements for the move, to organize child-centred activities such as child care, and to purchase the various new possessions which may be required following a change of house (Magdol 2002). As with employment-related moves, therefore, there may be gendered outcomes which mean that partners may have different views about the desirability of moving and its effects (Wiggins and Shehan 1994).

The stresses associated with longer distance moves may be greater than more local moves and an extensive literature documents the potential implications of international migration on mental health (Vega, Kolody et al. 1987; Bhugra 2004). Even longer distance moves within a country will likely disrupt local family and friend networks (Sluzki 1992; Magdol 2002) and there is evidence that children’s behaviour may be effected negatively by such disruption, with migrant children apparently suffering higher school dropout rates (Astone and Mclanahan 1994), poorer educational attainment (Ingersall, Scamman et al. 1989), more delinquent behaviour (Adam and Chase-Lansdale 2002), and higher rates of substance abuse (DeWit 1988). Such outcomes for children will inevitably impact upon the parents and may contribute to problems in any relationship, and frequent long- or short-distance moving is only likely to exacerbate such potentially negative effects (DeWit 1988; Wiggins and Shehan 1994).

In addition, as Boyle, Kulu et al. (2008) argue, factors related to the origin and destination of the moves may also influence union dissolution. The destination may offer new opportunities that affect partners differently. Quite simply, one partner may be happier with the new location than the other (Flowerdew and Al-Hamad 2004) and moves which separate partners for a period of time during the settling in period may be particularly difficult (Green and Canny 2003). Movers may also meet new potential partners (South and Lloyd 1994; South, Trent et al. 2001; Trent and South 2003), or may be exposed to different cultural contexts where separation is more socially acceptable. From an international migration perspective, Hirsch (2003) suggested that the feelings of anonymity that Mexican women in the US felt helped them break free from some of the gender norms prevalent in their home communities with resulting higher rates of separation.

Moving from a particular origin may also influence dissolution. Some live in communities that discourage separation and leaving such areas may reduce the social pressure to remain partnered. Such influences may be especially relevant for women (Rosenthal 1985).

There have even been some aggregate, ecological studies which compare divorce rates with mobility rates. These early geographical studies in Canada and the US (Cannon and Gingles 1956; Fenelon 1971; Makabe 1980; Wilkinson, Reynolds et al. 1983; Trovato 1986; Breault and Kposowa 1987) argued that population turnover, driven by migration, in the ‘frontier’ west could be related to the higher divorce rates observed there (although see Weed 1974; Glenn and Supancic 1984). The instability of these communities was hypothesized to influence individualism and to weaken social control over the actions of individuals – hence divorce which may have been frowned upon in more stable communities became more common. However, such ecological studies were unable to determine whether population turnover influenced union dissolution because of changes in community-level cohesion, or because the migrants themselves were more susceptible to separation.

Various other factors influence union dissolution beyond migration and mobility, which we consider in this study. The ‘independence hypothesis’ suggests that women who are employed and are more able to support themselves may have less to gain from remaining married if the relationship is deteriorating (Becker, Landes et al. 1977), although the evidence for this hypothesis remains mixed (Mason and Jensen 1995; Oppenheimer 1997; Chan and Halpin 2003). Cohabiting relationships have been argued to involve less ‘investment’ and are therefore expected to be easier to terminate than married relationships. (Bennet, Blanc et al. 1988; Hoem and Hoem 1992; Diekmann and Engelhardt 1999; Kiernen 1999; Jenson and Clausen 2003). A number of authors suggest that the presence of dependent children discourages union dissolution (Morgan and Rindfuss 1985; Waite and Lillard 1991; Berrington and Diamond 1999; Manning 2004), although Chan and Halpin (2003) suggest that children may actually increase the risk of union dissolution in Britain (see also Boheim and Ermisch 1999). Higher educational status among women is also expected to reduce the likelihood of separation (Morgan and Rindfuss 1985; Hoem 1997). And, the geographical location has also been examined, with rural dwellers being less likely to separate than urban dwellers (Balakrishnan, Rao et al. 1987; Dieleman and Schouw 1989; Lillard, Brien et al. 1995; South, Crowder et al. 1998; South 2001).

Our analysis therefore contributes to both the family migration and the union dissolution literatures. In a previous study, we explored the effects of moving on union dissolution using retrospective event-history data from Austria (Boyle, Kulu et al. 2008). The results from this analysis suggested that couples who moved frequently had a significantly higher risk of union dissolution than similar otherwise comparable couples. Here, we extend this literature by exploring whether similar effects exist in Britain, taking advantage of longitudinal panel data from the British Household Panel Study (BHPS). We are particularly interested in the effect of within nation migration of families on union dissolution, while controlling for other influential factors. Our hypotheses can therefore be divided into two sets of factors.

The first set relate to factors identified in the literature that are expected to be associated with union dissolution:

1. Cohabiting couples are more likely to separate than married couples.

2. The length of partnership will be negatively correlated with separation.

3. Older women will be less likely to separate.

4. The presence of dependent children will reduce the likelihood of separation.

5. Those in urban areas are more likely to separate than those in rural areas.

6. Women with higher qualifications will be less likely to separate.

7. Women in work will be more likely to separate.

More specifically, though, we are interested in the role of family migration, and we identify three hypotheses:

8. Migrants are more likely to separate than non-migrants.

9. Frequent movers are more likely to separate than less frequent movers.

10. Long distance migrants are more likely to separate than short distance migrants or non-migrants.

Data and Methods

The longitudinal data used in this analysis were drawn from the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS). We extracted information from waves A-K (1991–2002) for all individuals aged 16 and above who were in a couple (married or cohabiting) at wave A, or who formed a couple in subsequent waves. Individuals were dropped if the partners separated, as we were interested in the effect of moving together, but individuals were reintroduced if new unions were formed. The resulting dataset included 4,619 couples and 31,821 couple/wave observations. We modelled the women in these couples, and captured in the data were 772 separations and 2,503 moves.

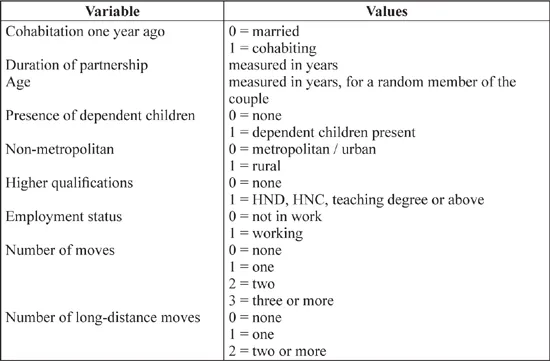

The dependent variable in the modelling was whether a couple separated (1) or not (0) and the independent control variables included: cohabitation (at t–1); the duration of the partnership; age; the presence of dependent children; whether the woman had higher qualifications; whether the woman was in work; and whether they lived in an urban or rural area (Table 1). Of particular interest was the effect of within country moves as couples on dissolution. The independent mover variables included: moves in the previous 1–3 years; the frequency of moves; and the distance of moves. All of these mover variables excluded moves in the year that a couple formed or separated.

Table 1.1 Variables

The modelling approach was a random effects logit model which deals efficiently with clustering of individuals in panel data (the repeated observations at each wave cannot be treated as independent of one another, so a standard logit model is inappropriate) and the results are presented as odds ratios. First, we fitted univariate models for each explanatory variable and then two separate multivariate models which focused on the number of moves and the number of long-distance moves, controlling for other variables expected to influence separation.

Results

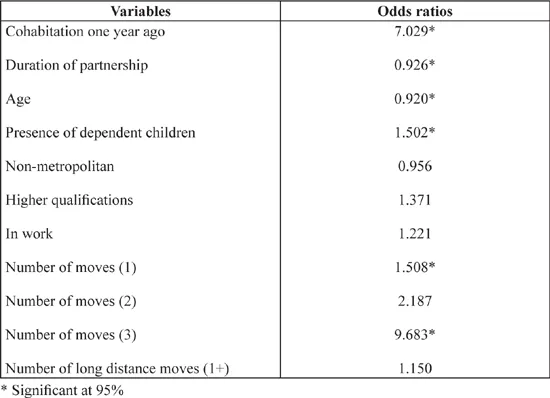

The results from the various models are displayed in Tables 1.2–1.4. Table 1.2 provides the univariate modelling results for each explanatory variable, showing that a number of these had a significant influence on separation. Cohabiting relationships were more likely to dissolve, older women were less likely to separate and the duration of the relationship was also negatively associated with separation. The presence of dependent children was positively and significantly related to separation for women, offering some support for Chan and Halpin’s (2003) finding. Some variables were not significant. Women with higher qualifications were actually more likely to separate, but this was marginally insignificant. A similar result was found for women who were working compared to those who were not – working raised the odds of separation, but not significantly. And those living in rural areas were less likely to separate, but not significantly so. Moving (once or three or more times; two moves was marginally insignificant) appears to be positively related to dissolution, while one or more long distance move was not significant.

Table 1.2 Univariate modelling results

The results in Table 1.1 treat each variable independently. In Table 1.3, we explore the effect of moving on union dissolution, controlling for the other explanatory variables in a multivariate model. Cohabiting relationships remained significantly more likely to end, with nearly three times the odds of married couples. Relationships that were longer or involved older women were significantly less likely to fail. Note that, controlling for these other variables, the presence of dependent children reduced th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Law and Migration

- Title Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Introduction

- Gender, Migration and Managing Family Life

- The Impact of Migration on Women's Careers

- Gender Perspectives on Immigration Control

- Index