eBook - ePub

Space in the Medieval West

Places, Territories, and Imagined Geographies

- 266 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Space in the Medieval West

Places, Territories, and Imagined Geographies

About this book

In the last two decades, research on spatial paradigms and practices has gained momentum across disciplines and vastly different periods, including the field of medieval studies. Responding to this 'spatial turn' in the humanities, the essays collected here generate new ideas about how medieval space was defined, constructed, and practiced in Europe, particularly in France. Essays are grouped thematically and in three parts, from specific sites, through the broader shaping of territory by means of socially constructed networks, to the larger geographical realm. The resulting collection builds on existing scholarship but brings new insight, situating medieval constructions of space in relation to contemporary conceptions of the subject.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Space in the Medieval West by Fanny Madeline, Meredith Cohen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European Medieval History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Places, Monuments, and Cities

Chapter 1

Squarely Built: an Inquiry into the Sources of Ad Quadratum Geometry in Lombard Architecture Between the Eleventh and the Twelfth Centuries

Emanuele Lugli

The Dynamism of Geometrical Design in the Middle Ages

If there is one thing that seems to unify medieval planning across geographical boundaries and time frames, it is ad quadratum geometry. With this expression, we refer to systems of proportional schemes derived from the components of the square, such as its side or its diagonal, which were combined to generate the plans of buildings.1 Scholars are convinced of the geometrical nature of design solutions since a long time and intensive research over the last decades has enriched our insight about its diverse local applications and cultural dimensions, which have now led to two promising paths of research.

First, since Lefebvre’s The Production of Space, where space was defined as the result of social relationships, geometrical schemes have been approached as formal mediations of political forces.2 Lefebvre thought that their study was conductive to the exposure of a society’s political structures, as did David Friedman, who in his Florentine New Towns, a book detailing the geometrical design of some fourteenth-century Florentine outposts, first revealed the historical production of such structures.3 It is important to stress that Lefebvre described social interactions as incessantly changing and such a dynamic picture spurred scholars to move past the idea of planning as a predetermined activity.4 In an age of unpredictable economic fluctuation and slow construction, medieval architects endorsed an open-ended design process, which relied on geometrical schemes and their creative, potentially never-ending concatenation of shapes, to maximize building flexibility.5

Such a dynamic flow also characterizes the second wave in current scholarship. Under growing pressure from anthropology and visual culture, geometrical schemes are perceived less as the application of theorems than as the outcomes of specific bodily performances.6 Measuring involves a motion of hands and eyes; the tracing a geometrical shape on the ground has many traits in common with a ritual performance or a dance (in the sense of a series of planned and controlled movements). As one of the key interests of politics is the control of bodies, the difference from Lefebvre’s theory may appear slight. Yet, whereas Lefebvre’s focus remains on the social infrastructure, this approach mostly turns to the technological, asking questions about the measurement standard medieval communities employed, what reference points builders took (did they consider the thickness of the walls or the diameter of columns when planning a building?), and what degree of error was tolerated. As we mostly lack historical information about such issues, these questions are largely frustrated, as Eric Fernie pointed out in a foundational essay.7 Still, these issues make us realize that measuring is not a neutral activity.8 And while searching for data that may cast some light on historical measuring, architectural historians now know that they must be explicit about the way they conduct their own surveys.

This chapter, a historical account of the plans of Modena and Cremona cathedrals aiming at refining some general prejudices about medieval geometrical planning, stems out of this twofold perspective. Both built in the first half of the twelfth century in Italy’s Po valley, these churches are often described as the products of a shared architectural culture, which is here confirmed by the retrieval of the same proportional schemes.9 Interestingly, these are described in coeval manuscripts that transcribe passages from late classical manuals for land surveyors and administrators that today go under the name of Corpus Agrimensorum Romanorum.

Scholars have known of the Corpus since the nineteenth century, yet most of them have marginalized its cultural relevance as second-string, with only few voices detaching themselves from the group.10 Such dismissal is still prevalent among architectural historians as centuriation—the Roman system of land division for whose preservation the Corpus was originally written—was thought to be unknown in the Middle Ages. A series of recent archaeological studies have however showed the contrary, thus confirming the historical plausibility of finding centuriation proportions in the cathedral of Modena and Cremona.11 This chapter, however, goes further as it contends that the centuriation was the very repository of geometrical schemes, thus arguing for a non-textual source for geometrical transmission. This hypothesis is supported by the cultural intensity of centuriation, which drew the curiosity of intellectuals such as Gerbert of Aurillac and whose features significantly shaped an array of spatial activities, from the gauging of measurements to the orientation of buildings.

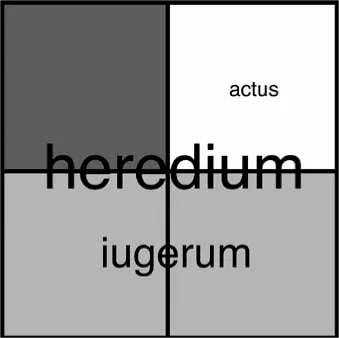

Roman Centuriation in the Po Valley

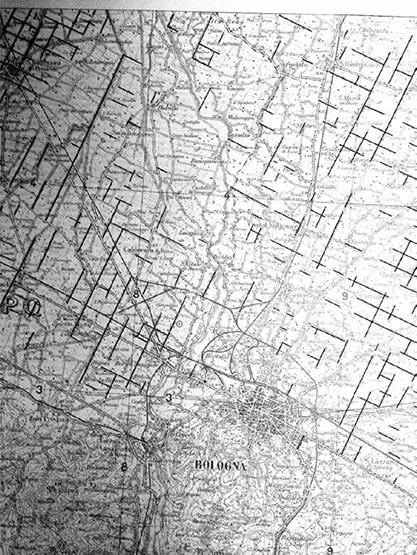

Centuriation is a vast, regular, chessboard-like grid of roads and canals, which was carried out by the Romans after conquering the area in the 190s BCE (see Map 1.1). Centuriating the land was the conclusive act of military conquest: it charted every bit of the territory, even marking areas far away from urban centers likely to remain undeveloped. Such spatial configuration had a variety of benefits. By turning land into a quantitative grid, it facilitated travel, the calculation of distances, and, as historians usually point out, the precise assignment of fields to settlers as well as the calculation of taxes.12 As we know from the Corpus, its basic unit was the centuria, a square measuring 20 actus per side (one actus = 35.48 m or 120 Roman feet of 29.73 cm).13 Two actus made one iugerum, and two iugera (or one heredium) usually constituted the size of the average plot assigned, by lot, to a family of colonists.14 Hence, the name “centuria” referred to the one hundred plots the area ought to create (one centuria = one hundred blocks of two square iugera) (see Figure 1.1).

Map 1.1 Extant centuriation reticulum near Bologna (map in the public domain). From Giovanna Bonora Mazzoli, “Persistenze della divisione agraria romana nell’ager bononiensis,” in Insediamenti e viabilità nell’Alto Ferrarese dall’età romana al Medioevo (Ferrara, 1989), 87–101

Centuriation guidelines, either parallel or perpendicular, were traced on the ground by the agrimensores, surveyors of great engineering expertise. To do so, they heavily relied on the groma, a wooden tripod supporting a horizontal metal cross from whose arms plumb-lines hang down.15 The groma was an instrument that operated by sight; the agrimensor established the direction of the new axis by aligning one plummet with its opposite and shouted to a collaborator where to position the stakes (dictare metas).16 To our eyes, it may seem a primitive technique, but it was a perfectly reliable instrument for short distances, such as those encompassing a few actus. Further, only by sight did the Romans manage to circumvent the complex calculations that the curvature of the earth and the slope of the ground would have required. The correct alignment of the stakes was automatically double-checked while enlarging the centuriation grid, but the real authentication came when measuring the sides of each actus by rods or ropes.17

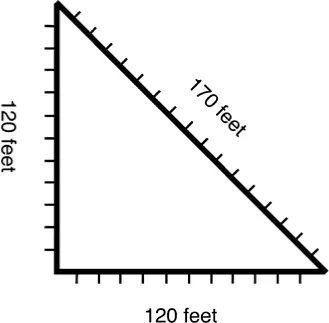

The rule is also at the core of ad quadratum planning. When designing a square, one can be sure that what was drawn is precise as the relationship between the sides of a square and its diagonal is fixed. Today we represent this relationship as √2, but in classical as well as in premodern times (that is, before the creation of irrational numbers), it was often seen as 17/12.18 To make sure that a square with sides of 12 braccia was exact, a medieval master would check whether its diagonal was 17 braccia (see Figure 1.2). If the diagonal did not correspond, one of the extremes of the square had to be repositioned to fulfill that condition. The Roman centuriation was the product of this simple geometrical relationship. Since the side of the actus measures 120 Roman feet, a surveyor could verify that the quadrangle he had just traced was a perfectly squared actus (120 × 120 feet) by checking that its diagonal measured 170 feet.

Figure 1.1 The proportional scheme of centuriation (Emanuele Lugli)

Figure 1.2 The relationship between side and diagonal in a square whose side is 12 braccia (Emanuele Lugli)

The surveying continued this way, as a strenuous process of trial and error (with stakes repositioned countless times and the operations jeopardized by sudden gusts of wind) and as a very delicate matter (its pace was determined by the fleeting disappearance of the tiny silhouette of a man behind two out-of-focus plumbs). Still, the agrimensores painstakingly managed to partition Rome’s vast and largely uncharted conquered territories, an extraordinary undertaking which, regrettably, is admired only by a few specialists.

Although designed to encompass slopes and even mountains, the centuriation crossed the Po river valley, Italy’s largest flatland, an ideal terrain of application. There, many square kilometers of centuriated area are still perfectly visible in the course of most of its streets and canals. Its preservation, to a large extent, depended on its astonishing precision. In the territory of Carpi, north of Modena, many Roman centuria are well preserved as their perimeters are marked by roads that are still in use. Their sides measure in average 706.1 m, with a margin of error of about 1.28 m per kilometer.19

Far from disappearing then, in medieval times many canals and streets that made up the centuriation remained where they were. Lots and fields filled the centuriation reticulum without compromising it. The archaeologists Carlotta Franceschelli and Stefano Marabini have even demonstrated that in the early Middle Ages the centuriation grid was expanded and new perpendicular streets and canals were created ex novo near Faenza, in the East sector of the Po valley, in the proportions of the centuriation.20 This suggests that Roman surveying techniques were consummately known at the dawn of the Middle Ages.

Centuriation Embodied: the Cathedrals of Modena and Cremona

A feature of the landscape, centuriation also became a magnetic grid for medieval planning, as most churches of the Po valley built between the eleventh and twelfth centuries conformed to its orientation.21 This includes all cathedrals, except that in Fidenza, and many important abbeys, such as San Zeno in Verona and San Silvestro in Nonantola. It is unsure when churches started following this orientation in spite of the religious diktat that favored solar coordinates. Without comprehensive statistical data (unfeasible, as we lack reliable dating for most Romanesque churches), we should rest with the vague hypothesis that the orientation never truly went out of focus. (After all, many medieval buildings, such as the Faenza baptistery, were created in early Christian times and followed the reticulum by default.)22 Yet, the case of Modena cathedral, for which we possess a bit more information, points to a different interpretation. Far from continuing a time-honored habit, the orientation of the twelfth-century church was deliberately corrected so as to follow Roman centuriation.

When the architect Lanfrancus was summoned in 1099 to build a...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Maps

- List of Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- PART I PLACES, MONUMENTS, AND CITIES

- PART II SPATIAL NETWORKS AND TERRITORIES

- PART III CARTOGRAPHY AND IMAGINED GEOGRAPHIES

- Frequently Cited Sources

- Index