![]()

1Dramatis personae

… how we view ourselves, and how we represent ourselves to others, is indissociable from the stories we tell about our past.

(Susan Rubin Suleiman, Crises of Memory and the Second World War)1

[We] use the term ‘family romances’ to indicate a ‘family saga’, that is, the story a family tells about its own history, a mixture of memories, omissions, additions, fantasies and reality, which has a mental reality for the children raised in that family.

(Anne Ancelin Schützenberger, The Ancestor Syndrome: Transgenerational Psychotherapy and the Hidden Links in the Family Tree)2

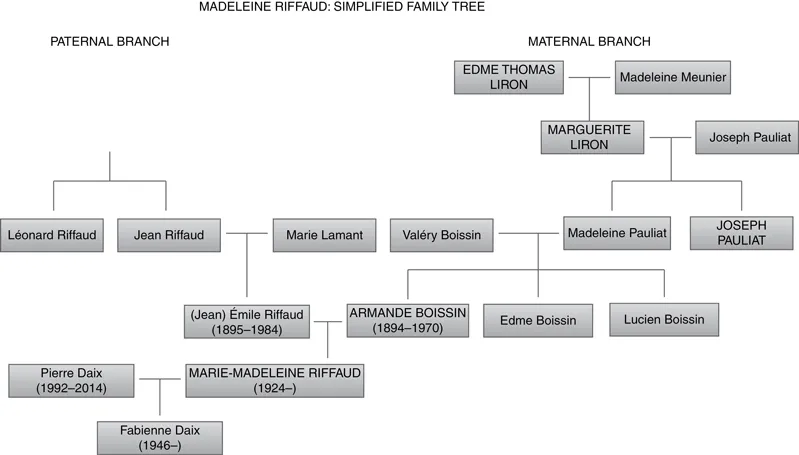

The past is not simply what a person inherits. It is also what they make it – the people and events they choose to remember and the way they work them into their life-stories. In this respect, much of the material in this biography is based on the portrait Riffaud has drawn of herself with its chosen angles of perception, its highlights and, above all, its relations to others. From childhood, Riffaud was very aware of her family tree and as an adult she chose to identify with one ancestor in particular who became as important as living friends and relations in her accounts of her personal history and her ‘family romances’.3 Edme Thomas Liron (1806–1869) is the ancestor through whom she identifies her French roots as well as her geneaological ones, and he has remained a key figure in her life right through into her adult years. The autobiographical manuscript Liron completed in 1869 was a point of reference for Riffaud’s 1994 autobiography4 and it is therefore a point of reference for the present work also.

Riffaud’s interest in, and even obsession with, this character from her past was clear from my first interview with her in 2010, when she began telling a story about her ancestor even before she had begun to talk about the events of her own life. Her preoccupation with great-great-grandfather Liron proved to be illustrative of another important feature of her as a person: namely, the place she has given to storytelling and the poetic imagination. Language, in the form of oral and written narrative, has been the means by which her understanding of self and world has been forged. The words of ancestor Liron have been transmitted through the generations in her family tree in the form of a manuscript that has served as a touchstone for her understanding of what it means to be a rebel. His is the ‘original’ portrait of rebellion that hers imitates. After researching his life in the 1990s, Riffaud was able to extend his story and, literally, to write it into her own. She refers to him in her autobiography, her poetry, and in her reflections on the war zones she covered in her journalism. For Riffaud is a story-teller like her ancestor, and like him, too, she uses narrative to serve the transformative vision of society she believes in. Resistance Heroism and the End of Empire thus refers to a double portrait, a reinscription of a heroic narrative that has been written before.

In his Philosophical Investigations Wittgenstein wrote about how seeing connections between family members by identifying repeat features serves as a model for the way in which human understanding works as a whole.5 Perspicuous understanding, ‘the kind of understanding that consists in “seeing connections”’, is undoubtedly at work in the genre of biography that presents an initial picture of a person through their ‘connections’ with others.6 In Riffaud’s case, her ‘perspicuous understanding’ of her connection to Liron has meant that she has been able to link her family story to the story of her country, making out of both of them a narrative of intergenerational legacies and inherited features. The simplified family tree below shows the line of inheritance from Liron through to Riffaud, indicating in capitals those who have carried the encoded family saga that is at the heart of Riffaud’s views of personal and national history.

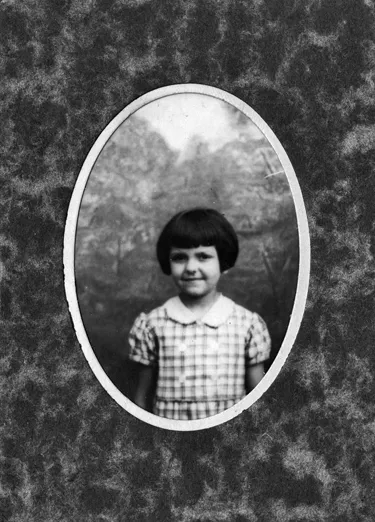

Émile and Armande

Marie-Madeleine Riffaud was born in Arvillers in the Somme on 23 August 1924. Armande née Boissin (1894–1970) and Jean Émile Riffaud (known as Émile) (1895–1984) had moved to the area the previous year, thus beginning family life in a place associated with some of the bloodiest fighting of the First World War. It was while fighting on the Somme battlefield that Émile had been wounded as a soldier in 1916.7

However, both Émile and his wife were teachers and after their marriage, the young couple found that the only posting that would enable them to stay together as a couple was in the Somme district. Known in the teaching fraternity as the ‘zone rouge’ because few sought employment there,8 the landscape was badly scarred by reminders of the conflict – kilometres of graveyards, rusted wire and unexploded shells still embedded in the countryside.

As their choice of profession suggested, Madeleine’s parents valued education highly. They had both come from poor families where education was a prize worth striving for rather than a burdensome rite of passage. Madeleine’s mother, Armande Boissin, was an orphan whose mother had died of tuberculosis and whose education was paid for by her maternal grandfather. Madeleine’s father, Émile Riffaud, was the first boy in his family to receive a formal education, and the only boy at his school who didn’t own a ‘proper’ pair of shoes. Instead, he wore wooden clogs, the footwear of the poor who could not afford leather. Like his future wife, he went on to win prizes and became a teacher who was recognised in the local community for his contribution to education. As well as teaching at the local village school of Folies, Émile was made headmaster of the school in Bouchoir, about one and a half kilometres away from Folies, and an officer of the Academy in 1937. He continued working in the education system right up until his death in September 1984.

Riffaud’s parents saw themselves as republicans and were proud of a heritage that linked their country’s constitution with the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Republicanism, however, includes many shades of political and philosophical distinction, and in their case, one of the most obvious differences between their worldviews had to do with religion. Where Madeleine’s father was agnostic and freethinking, her mother respected the authority of the Catholic Church. So although she taught in a secular education system, as did her husband, Armande ensured that her only daughter, Madeleine, received a Catholic upbringing through regular attendance at mass. In this respect, the maternal and paternal branches of the family tree connect Riffaud to two different strains of republicanism that have shaped French society, where laïcité, or secularism, is still a passionately debated feature of the country’s education system and its constitution. Because of this, perhaps, Riffaud has never felt it necessary to choose exclusively between left-wing, secular republicanism and the Catholic faith. As an adult, she embraced both, seeing the social ideals of communism (she joined the Party in 1942) and Christianity as perfectly compatible.

The paternal branch

Émile was born on 18 February 1895 at St Bonnet de Bellac to Jean and Marie Riffaud. He belonged to what was called the ‘génération sacrifiée’ of the First World War, in which nearly one and a half million Frenchmen died. Like many of his countrymen, Émile retained a lifelong hatred of warfare, having suffered its effects on his health while knowing that he was one of the ‘lucky’ ones. A letter to his parents, dated Sunday 21 May 1916, mentions wounds that have healed cleanly and left him with just ‘a little’ nerve trouble in his hand and leg – the ‘trouble’ would recur intermittently in the form of pain and depression for the rest of his life.9 Madeleine has a photograph of Émile from this time, showing a handsome soldier, his leg swathed in bandages: the wounded hero with whom her mother fell deeply in love.

During the occupation of France in the Second World War, Émile never joined the Resistance, despite an intense dislike of the Vichy regime and its policies. He remained what was known as a ‘pacifiste intégral’, a pacifist opposed to war in any form, although he would not have recognised himself in the academic definition of the term as one who not only ‘refused war on principle’ but who also, by implication, ‘preferred servitude’.10 Where some ‘pacifistes intégraux’ made an easy transition from pacifism to collaboration, Émile was not of their number. Protective of his family and of the schoolchildren in his care, he was especially impressed by the intelligence and character of the young Polish refugees in his classroom whose diligence he sometimes compared unfavourably with that of his daughter. To keep the refugees safe, he regularly falsified information in response to letters from the Teaching Academy, seeking to establish if there were any Jewish children at local schools. ‘None’, he always replied. And so, Riffaud suggests, ‘il faisait des choses quand même, de petites choses’ (‘so he did do some things, little things’). Similarly, although the presence of German soldiers in his country was bitterly resented and Émile avoided them when he could, he treated neither Nazi soldiers nor their Vichy collaborators with open hostility. His most characteristic act, in Riffaud’s mind, occurred after he had arrived home late from school one winter’s night, after finding an unexploded shell in the road. Not wanting anyone, whatever their nationality, to be hurt, he had removed it, lifting it carefully in both hands and placing it at the bottom of a ditch. Later, Riffaud would harbour resentment against her father for his lack of support for radical resistance. Once she sent him a printed resistance tract when she was a student in Paris, and he responded with an angry letter, telling her she was too young to be ‘poking her nose’ into such things and forbidding her to be involved. She did not take his advice.

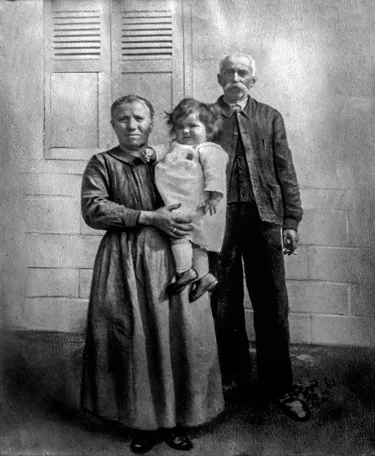

Madeleine loved her paternal grandfather, Jean, dearly and describes the times she spent in his company when she was growing up (he lived with them when he was elderly) as the happiest moments in her childhood.

The most terrible moment in Madeleine’s young life, by the same token, was when Jean died. He taught her songs from France’s left-wing past, took her on rambling walks through the forest and impressed on her the importance of loving all things that grow in gardens. ‘I have never in my life intentionally damaged a plant … My gardener Grandfather forbad it, and taught me respect for flowers.’11 Traces of his influence can be seen today in the plants that spread in profusion in Riffaud’s Paris apartment.

The maternal branch

Riffaud’s mother was born Armande Boissin in 1894 in Djerba, Tunisia, 13 years after the French had conquered the country and placed it under the authority of the French Resident-General.12 By virtue of her birthplace, she was associated with a colonial system that her daughter would one day vilify in her writing. Her father, Valéry Boissin, was a lowly member of the Armée d’Afrique, the French colonial army that upheld the authority of the French protectorate in the country. V...