- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Trends in Chinese Education

About this book

This book considers a wide range of key developments and key areas of debate in China's education system. Marketization, quality assurance, and issues of inequality and gender are all discussed, as are expansion in the primary, secondary and tertiary sectors, the impact of globalization, and the influence of education on China's economic growth. The book, which comprises contributions from many leading authorities, will be of great interest both to comparative education specialists, and also to all those interested in China's rise and development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Trends in Chinese Education by Chen Hongjie, W. James Jacob, Chen Hongjie,W. James Jacob in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 A review of key trends in Chinese education

A review of key trends in Chinese education

The world’s largest education system stems from millennia-old traditions that place great value and emphasis on learning, teaching, and the central role that institutions of learning at all levels should and do play in the education process. Parents and grandparents teach children from very early ages to cherish opportunities to learn. Chinese children in rural and urban settings dream of completing their basic and secondary education and performing well on the national higher education entrance exam (Gaokao, 高考). As it was in ancient times, economic opportunities in China tend to increase with the more education individuals attain (Jiang 2014).

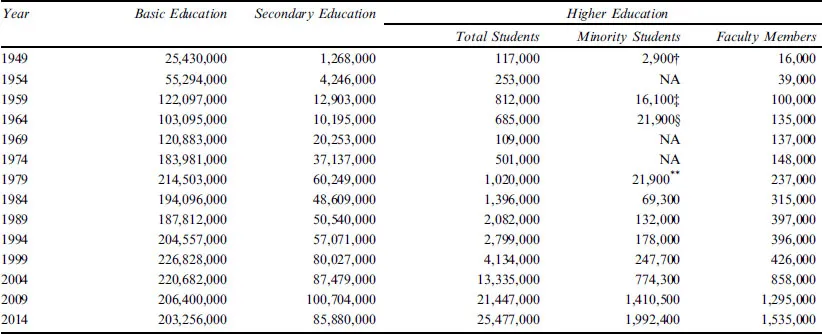

In China, basic education comprises pre-school education, primary education and junior secondary education (nine-year compulsory education), senior secondary education, and special education. To remain consistent with the historical data, secondary education in this chapter refers to specialized secondary education, regular secondary education, and secondary vocational education (see Table 1.1). Given the state of the education system that the PRC inherited in a postwar context in 1949, the government has made tremendous progress in terms of reducing its national illiteracy rate and providing basic education opportunities to the masses. Yet even with all of this progress, several social justice issues remain (Jacob 2006; Jacob et al. 2015). A large percentage of eligible cohort students are unable to continue on with secondary and higher education schooling. Roughly 42% of all eligible students move on to attend secondary education, and only 30% of secondary students move on to pursue a higher education degree (Ministry of Education 2015).

Ethnic minority students struggle with issues of language, culture, and identity. Local, national, and increasingly global environmental push and pull factors create a perfect storm context that often prevents ethnic minority students from wanting to learn and use their indigenous languages and cultures in daily life, let alone in school and employment settings (Jacob 2015; Jacob et al. 2015).

Gender disparities still remain, with females having fewer mean years of schooling than males (UNDP 2014). There are also regional disparities, where the vast majority of the top schools and HEIs are located in the eastern region, and especially in major urban centers like Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shanghai. Since education is largely funded at the local level, wealthy cities and provinces tend to offer greater education opportunities than what is offered in rural and remote locations. Students of all ages from rural and remote regions of the country are at an added disadvantage due to geography (Fleischer et al. 2011; Hansen 2013; Heckman & Yi 2012; Jacob 2004). Other trends include an increase in the number of migrant children attending school in locations where their parents are working.1 Schools have the potential to provide safe havens for these migrant children (Gao et al. 2015). But seasonal jobs and other life-changing events make it difficult for migrant children to maintain steady enrollment over long periods of time in any one school (Liu & Jacob 2013). While some urban centers open up public schools to migrant children, others do not. Migrant students are often forced to enrol late and endure frequent moves that are often in the middle of the school year, which puts them at a significant disadvantage compared to their local peer counterparts. Curricula also vary from province to province, so changing schools is often difficult for many migrant children in terms of being able to remain current with differing curricular requirements and teaching styles. Chen Yuanyuan and Shuaizhang Feng (2013) also note how many migrant children are prohibited from attending public schools because they do not have local household registration status. Many migrant children are forced to enrol in schools established specifically for migrant children (Lu & Zhou 2013). Being able to meet the continuing needs of migrant children with regard to basic, secondary, and higher education will be an ongoing challenge the country will face for many years to come.

Table 1.1 Student enrollment trends in basic, secondary, and higher education, 1949–2014

NBS (2005, 2015), Ministry of Education (2015), and State Ethnic Affairs Commission and NBS (2012).

Notes: †1952 data. ‡1957 data. §1965 data. **1978 data.

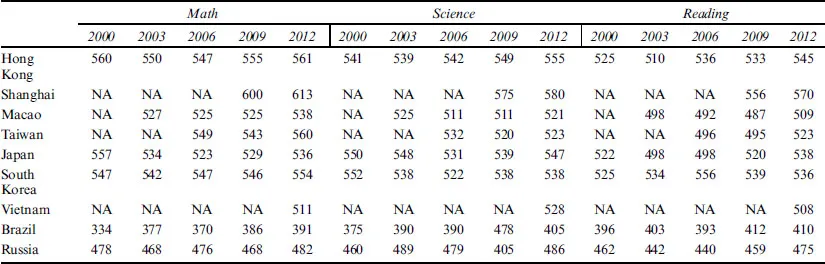

While it is impossible to determine how the entire country would fare on the global stage on the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in the areas of math, science, and reading, we do have a snapshot from two of China’s largest cities – Hong Kong and Shanghai. Both consistently score among the top five participating countries and economies, and in 2012 Shanghai led all countries and economies in all three categories (see Table 1.2).2

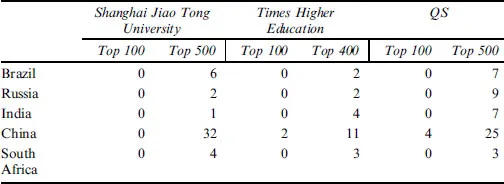

Based on global rankings of HEIs, China leads the other BRICS nations with several world-class universities and thirty other national universities that have established international renown (Table 1.3).3 In recent years, China has risen to become a top destination for foreign students studying abroad (Table 1.4). Higher education students from every major global region study in China, with the top ten origin countries in 2014 being South Korea, the United States, Thailand, Russia, Japan, Indonesia, India, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, and France. In 2013, the top seven destination countries for Chinese students studying abroad were the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea.

Three animals – dragons, tigers, and turtles – in Chinese culture serve as appropriate analogies to the important role that Chinese students studying abroad play in the future development of the nation’s economic and cultural development. The dragon is a leading figure in Chinese history and symbolizes royalty, power, and eternal progress. When children perform well on the Gaokao and gain admittance into a prestigious university, they are often referred to afterwards as a dragon in the family. Tigers are also important in Chinese culture and symbolize potential for growth, learning, and progress. Children and students of all ages are often viewed as crouching tigers with hidden talents and latent potential. Hǎiguī (海归) or the metaphor “sea turtles” (hǎiguī, 海龟) is a colloquial term often used in China and in the literature to refer to those who return to China after having studied abroad. The many thousands of Chinese who return to China after studying abroad help build local and national businesses and contribute to their communities through service and employment (Jacob et al. 2015).

Table 1.2 PISA exam results for Hong Kong, Shanghai, and other East Asian neighbors, 2000–2012

OECD (2000, 2003, 2006, 2009, 2012).

Table 1.3 Comparison of ranked HEIs in BRICS countries, 2015

Shanghai Jiao Tong University (2015), THE (2015), and QS (2015).

Table 1.4 Study abroad numbers, 1949–2014

| Year | Chinese Students Studying Abroad | Foreign Students Studying in China |

|---|---|---|

| 1949 | 35* | 33* |

| 1954 | 1,518 | 324 |

| 1959 | 576 | 259 |

| 1964 | 650 | 229 |

| 1969 | NA | NA |

| 1974 | 180 | 378 |

| 1979 | 1,777 | 440 |

| 1984 | 3,073 | 1,293 |

| 1989 | 3,329 | 1,854† |

| 1994 | 19,071 | 43,712‡ |

| 1999 | 23,749 | 44,711 |

| 2004 | 114,682 | 110,844 |

| 2009 | 229,300 | 238,184 |

| 2014 | 459,800 | 377,054 |

Sources: China Association for International Education (2015), NBS (2005), Ernst & Young (2014), Li (2000), and Yu (2009).

Notes: *1950 data, †1988 data, and ‡1997 data.

SCImago first began collecting national citation data in 1996, when China ranked ninth overall with 28,630 citable documents (Table 1.5). In 1996, Russia led the BRICS countries with 31,425 citable documents. Since 1997, China has remained the clear leader among BRICS countries and ranks second only to the United States as of 2014. The dramatic growth China has experienced has remained significant from 1999 to 2014. Based on the most recent growth data available on academic publications as portrayed in Table 1.5, China will soon overtake the United States as the leading nation in academic knowledge production.

Table 1.5 Citable documents by BRICS countries, 1999–2014

| 1999 | 2004 | 2009 | 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 12,582 | 21,935 | 43,959 | 56,368 |

| Russia | 31,036 | 35,997 | 37,487 | 49,018 |

| India | 22,776 | 32,948 | 62,976 | 106,078 |

| China | 39,037 | 107,509 | 296,050 | 438,601 |

| South Africa | 4,626 | 6,397 | 10,242 | 16,215 |

Sources: SCImago Lab (1999, 2004, 2009, 2014).

An introduction to this volume

This edited volume treats many key trends in Chinese education that are of significance for the discourse on comparative, international, and development education. These trends often shape how education institutions at all levels adapt to dynamic local and global forces. By understanding these trends and their influences, we hope to shed some light on possible future directions for education in China and the significance thereof for comparative education.

Key education trends that will be covered include issues relating to social justice, curriculum content, teacher preparation (both pre- and in-service teaching), administration, infrastructure development, quality, and governance. This volume is structured around current education trends at the national and local levels. The broad themes contained in the following fourteen chapters are as follows:

- Historical overview of education policy debates

- Marketization policy trends of education

- Quality assurance of higher education

- Study abroad experiences of Chinese higher education students

- Globalization’s impact on adult education policies

- Education’s influence on economic growth patterns

- Inequity in educational attainment

- Theoretical influences on education

- Expansion policies of primary, secondary, and higher education subsectors

- Gender policies and educational reform trends

- History of technology education shifts

This volume is timely in that it provides contributions from leading scholars and practitioners in the field of Chinese education. Many of the topics covered in this volume are relevant for anyone interested in learning about current trends in the world’s largest education system. The following chapters provide important insights into furthering policy debates and education reform planning initiatives.

In Chapter 2, Ding Xiaohao, Yu Hongxia, and Yu Qiumei discuss the returns on education of all levels and their changes for urban residents in China from 2002 to 2009. The analysis is based on the statistics of household survey data provided by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). The returns were calculated using the ordinary least squares (OLS) method, which includes three empirical analyses: (1) the ordinary Mincer equation, (2) the extended Mincer equation, and (3) the time trend of education returns variation. Generally, the findings show that the returns on education during this period failed to show an increase and gradually flattened out with very little fluctuation. The authors argue that the returns on the next level of education became an important motivation to pursue further education. However, over time the returns failed to keep an upward trend; even that of senior high school to technical college levels declined during the 2002–2009 time period, while the returns on bachelor’s and master’s degrees remained flat. Similarly, the results of the extended Mincer equation showed that only the net returns on junior high school climbed from 2002 to 2008, but they then declined in 2009 while the net returns of other levels fluctuated or fell slightly. The results of time trend analysis also show a similar tendency. Only the returns from completing junior high school showed a steady increase, while returns from the other education levels remained constant or even fell slightly. From one perspective, the slow growth of returns on education can raise the alarm for education institutions in China. On the other hand, these findings may motivate people to pursue higher education or improve the quality of their skills and overall returns on their education investment. The authors also conclude that technology will be an important factor when it comes to helping reduce the costs of education at all levels, and that it will thus improve returns on education.

In Chapter 3, Yue Changjun discusses the factors that influence the satisfaction of higher education graduates in China. The analysis derived from a survey done by Peking University in 2011. The survey covered thirty higher education institutions (HEIs) in eight provinces in the east...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of illustrations

- List of contributors

- List of acronyms and abbreviations

- 1. A review of key trends in Chinese education

- 2. Research on returns on education at all levels and changes for

- 3. Analysis of factors affecting Chinese higher education graduates” employment satisfaction

- 4. Studying abroad or internationalizing on campus: university students” global competence training

- 5. The influence of higher education on student development

- 6. Decontextualization and recontextualization: understanding

- 7. State and public education: a new analytical framework

- 8. Technology in the development of education

- 9. Education”s role in economic growth patterns

- 10. The political logic of non-government/private education (NGPE) in rural China: Evidence from a northern county

- 11. Shaking off adaptation theory, a historical misconception in higher education

- 12. Donor behavior, donation income, and Chinese higher education institutions

- 13. Changes in knowledge production and diversified models of academic research within world-class universities

- 14. Changes in knowledge production and diversified models of academic research within world-class universities

- 15. An examination of the ‘engineer of human souls’ metaphor

- Index