Overview

Genre studies incorporate a variety of frameworks used to analyse a range of textual genres, constructed, interpreted and used by members of various disciplinary communities in academic, professional, workplace and other institutionalised contexts. The analyses range from a close linguistic study of texts as discursive products, and spanning across to investigations into dynamic complexities of communicative practices of professional and workplace communities, to a broader understanding of socio-cultural and critical aspects often employed in the process of interpreting these textual genres in real-life settings (Miller, 1984; Swales, 1990; Bhatia, 1993; Bazerman, 1994). Some studies go further in an attempt to understand the nature of discursive practices of various disciplinary cultures, which often give shape to these communicative processes and textual genres (Bhatia, 2008a). Others tend to develop awareness and understanding of genre knowledge, which can be seen to be a crucial factor in genre-based analyses as situated cognition related to the discursive practices of members of disciplinary cultures (Berkenkotter and Huckin, 1995). In many of these analyses the cooperation and collaboration of specialists provide an important corrective to purely text-based approaches (Smart, 1998). In order to appreciate this increasingly complex and dynamic development in genre studies, one needs to have a good understanding of some of the key aspects of the analysis of language use that lead to some of these interesting and insightful developments in genre theory.

Swales (2000), referring to the early work of Halliday et al. (1964), rightly pointed out that their work on register analysis offered a simple relationship between linguistic analysis and pedagogic materials based on relatively ‘thin’ descriptions of the target discourses. Often it is found that outsiders to a discourse or professional community are not able to follow what specialists write and talk about even if they are in a position to understand every word of what is written or said (Swales, 1990). Being a native speaker in this context is not necessarily beneficial if one does not have enough understanding of more intricate insider knowledge, including conventions of the genre and professional practice. It is hardly surprising, then, that in subsequent years the English for specific purposes (ESP) tradition was heavily influenced by analyses of academic and disciplinary discourses within the framework of genre analysis (Swales, 1990; Bhatia, 1993), which, as pointed out by Widdowson (1998), was a significant advance on register analysis. He highlighted this aspect of communicative efficiency through genre knowledge, when he argued:

It is a development from, and an improvement on, register analysis because it deals with discourse and not just text; that is to say, it seeks not simply to reveal what linguistic forms are manifested but how they realize, make real, the conceptual and rhetorical structures, modes of thought and action, which are established as conventional for certain discourse communities.

(Widdowson, 1998: 7)

The rationale for such developments is that communication is not simply a matter of putting words together in a grammatically correct and rhetorically coherent textual form, but more importantly, it is also a matter of having a desired impact on the members of a specifically relevant discourse community, and of recognizing conventions constraining how the members of that community negotiate meaning in their specialised contexts of language use. In this sense, communication is more than knowing the semantics and lexico-grammar; in fact, it is a matter of understanding ‘why members of a specific disciplinary community communicate the way they do’ (Bhatia, 1993, 2004). This may require, among a number of other aspects of shared understanding, a discipline-specific knowledge of how professionals conceptualize issues and talk about them in order to achieve their disciplinary and professional goals. Many of these crucial aspects of shared understanding in discourse and genre studies have traditionally been subsumed under context. Without getting into any form of elaborate specification of context in this chapter, I would like to highlight a specific aspect of context, which, in my view, accounts for, and at the same time explains some of the most significant aspects of genre construction and interpretation of disciplinary, professional and other institutional actions.

Context in genre analysis

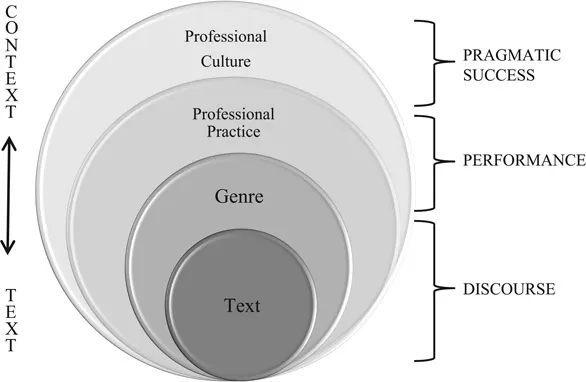

Context, though crucial in any form of discourse analysis, has traditionally been assigned a relatively less important value in the analysis of academic and professional genres. In the early conceptualizations of genre (Swales, 1990; Bhatia, 1993) the focus was primarily on text, and context played a relatively modest background role. However, in more recent versions of genre analysis (Swales, 1998; Bhatia, 2004, 2008a, 2008b) context has been assigned an increasingly central role, redefining genre as a configuration of text-internal as well as text-external resources, highlighting two kinds of relationships involving text and context. Interrelationship between and across texts, focusing primarily on text-internal properties, has been viewed as intertextual in nature, whereas interactions and appropriations across genres, professional practices, and even disciplinary cultures resulting primarily from text-external factors are seen as interdiscursive in nature. Intertextuality has been given considerable attention in discourse analysis; interdiscursivity, however, has attracted relatively little attention, especially in genre theory. Drawing evidence from a number of professional settings, in particular from corporate disclosure practices, international commercial arbitration practices and philanthropic fundraising practices, I will explore the nature and function of interdiscursivity in genre theory in subsequent chapters, claiming that interdiscursivity is the function of appropriation of generic resources, primarily contextual in nature, focusing on specific relationships between and across discursive and professional practices as well as professional cultures. In this opening chapter, I would like to point out that although text-internal factors have been central to our understanding of the complexities of professional genres, which are typically used in professional, disciplinary, institutional, as well as workplace contexts, there is a need to pay more attention to text-external factors. In other words, it is not sufficient to only analyse and account for textualisation of dis-cursive practices; it is more important that we address the role such discursive practices play in the achievement of professional actions – that is, professional practices as well as professional cultures. I will also claim that discourse essentially operates at four rather distinct, and yet overlapping, levels, and therefore, can be analysed as such. This is represented in diagram 1.1 below:

Diagram 1.1 Levels of discourse realisation

Discourse as text refers to the analysis of language use that is confined to surface-level text-internal properties of discourse, which include formal, as well as functional aspects of discourse – that is phonological, lexico-grammatical, semantic, organisational, including intersentential cohesion, and other aspects of text structure, such as ‘given’ and ‘new’, or ‘theme’ and ‘rheme’ (Halliday, 1973), or information structures, such as ‘general-particular’, problem-solution, etc. (Hoey, 1983), not necessarily taking into account context in any depth. Although discourse is essentially embedded in context, discourse as text often excludes any in-depth analysis of context, except in a very narrow sense of intertextuality to include interactions with surrounding texts. Similarly, emphasis at this level of analysis is essentially on the properties associated with the construction of the textual product, rather than on the interpretation or use of such a product. It largely ignores the contribution made by the writer or reader on the basis of what he or she brings to the construction or interpretation of the textual artefact, especially in terms of the knowledge of the world, including the professional, socio-cultural and institutional knowledge as well as experience that one is likely to use to construct, interpret, use and exploit such a discourse.

Discourse as genre, in contrast, extends the analysis beyond the textual output to incorporate context in a broader sense to account for not only the way text is constructed, but also the way it is likely to be interpreted, used and exploited in particular contexts, whether social, institutional or more narrowly professional, to achieve specific goals. The nature of questions addressed in this kind of analysis may often be not only linguistic but also socio-pragmatic and ethnographic. This kind of grounded analysis of the textual output has been typical of any framework within genre-based theory (Swales, 1990; Bhatia, 1993). In its early form, genre theory was primarily concerned with the application of genre analysis to develop pedagogical solutions for ESP classrooms. For more than thirty years now, it is still considered one of the most popular and useful tools to analyse academic and professional genres for ESP applications.

In my later work (Bhatia, 2004), which was an attempt to develop genre analytical framework further in order to understand the much more complex and dynamic real world of written discourses, my intention was to move away from pedagogic applications to ESP. My aim was, first, to focus on the world of professions, and second, to be able to see as much of the elephant as possible, as the saying goes, rather than only a part of it like the six blind men. I believe that all frameworks of discourse and genre analysis offer useful insights about specific aspects of language use in typical contexts, but most of them, on their own, can offer only a partial view of complete genres, which are essentially multidimensional. Therefore, it is only by combining various perspectives and frameworks that one can have a more complete view of the elephant. Hence, I felt there was a need to combine methodologies and devise multidimensional and multiperspective frameworks. My proposal to introduce a three-space model was an attempt in this direction (Bhatia, 2004). This was also a significant development for me in another respect, as this was an attempt to distinguish and at the same time, relate discursive practice to professional practice.

The above two phenomena were never clearly distinguished in discourse analytical literature. Discursive practices, on the one hand, are essentially the outcome of specific professional procedures, and on the other hand, are embedded in specific professional cultures. Discursive practices include factors such as the choice of a particular genre to achieve a specific objective, and the appropriate and effective mode of communication associated with such a genre. Discursive procedures are factors associated with the characteristics of participants who are authorized to make a valid and appropriate contribution; participation mechanism, which determines what kind of contribution a particular participant is allowed to make at what stage of the genre construction process; and the other contributing genres that have a valid and justifiable input to the document under construction. Both these factors, discursive practices and discursive procedures, inevitably take place within the context of the typical disciplinary and professional cultures to which a particular genre belongs. Disciplinary and professional cultures determine the boundaries of several kinds of constraints, such as generic norms and conventions, professional and disciplinary goals and objectives, and the questions of professional, disciplinary and organizational identities (see Bhatia, 2004). Professional practices, on the other hand, are actions which may not necessarily be achieved wholly through discursive artefacts, and are viewed as successful achievement of the typical objectives of a specific professional community. Obviously, the two concepts (i.e., discursive and professional practices) are closely related, in that one is significantly instrumental in the achievement of the other, and hence the close relationship between the two is crucial for bridging the gap between the academy and the professions, although it is possible to focus either on discursive practice, as was done within genre analysis that focuses on discursive products, or to focus on professional practice, in addition to the former.

In the context of this development, it is also important to point out that in the early years of genre analysis, especially in the 1990s, there was relatively little direct discourse analytical work in the available literature published in other disciplinary fields; the situation, however, in the last few years changed considerably as many professions have made interesting claims about the study of organisations, professions and institutions based on evidence coming from different kinds of analyses of discourse, in particular Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). There has been a substantial increase in research efforts to consider the contributions of discourse analytical studies in disciplinary fields such as law, medicine and healthcare, accounting and management, science and technology, where there is now a better understanding of the role of language not only in the construction and dissemination of disciplinary knowledge, but also in the conduct of professional practices (see for instance, Grant et al., 2001; Grant and Hardy, 2003; Grant et al., 2004).

There is thus a significant recognition of the fact that many of these practices can be better understood and studied on the basis of communicative behaviour to achieve specific disciplinary and professional objectives rather than just on the basis of disciplinary theories. In one of the projects, where I investigated corporate disclosure practices through their typical communicative strategies of putting together a diverse range of discourses (accounting, financial, public relations, and legal) to promote their corporate image and interests, especially in times when they faced adverse corporate results, so as to control any drastic share price movement in the stock market, I discovered that it was not simply a matter of designing and constructing routine corporate documents, such as the annual corporate reports, but was part of a strategically implemented corporate strategy to exploit interdiscursive space to achieve often complex and intricate corporate objectives through what I have referred to as ‘interdiscursivity’ (Bhatia, 2010), and to which I shall return in Chapter 3.

This idea of studying professional practice through interdiscursive exploitation of linguistic and other semiotic resources within socio-pragmatic space was also the object of undertaking in another project, in which I had collaboration from research teams from more than twenty countries consisting of lawyers and arbitrators, both from the academy as well as from the respective professions, and also discourse and genre analysts, which helped us to investigate the so-called colonization of arbitration practices by litigation processes and procedures. To give a bit of background, arbitration was originally proposed as an ‘alternative’ to litigation in order to provide a flexible, economic, speedy, informal and private process of resolving commercial disputes. Although arbitration awards, which are equivalent to court judgments in effect, are final and enforceable, parties at dispute often look for opportunities to go to the court when the outcome is not to their liking. To make it possible, they often choose legal experts as arbitrators and counsels, as they are likely to be more accomplished in looking for opportunities to challenge a particular award. This large-scale involvement of legal practitioners in arbitration practice leads to an increasing mixture of rule-related discourses as arbitration becomes, as it were, colonized by litigation practices, threatening to undermine the integrity of arbitration practice, and in the process thus compromising the spirit of arbitration as a non-legal practice (see Bhatia et al., 2008, 2012; Bhatia, 2011a, 2011b, 2011c). I will give a detailed account of this study in Chapter 4.

The evidence from the studies referred to above came from the typical use of communicative behaviour, both spoken as well as written, of the participants and p...