![]() PART 1

PART 1

Women and Men![]()

Chapter 1

“If I Can Make It There”: Oz’s Emerald City and the New Woman

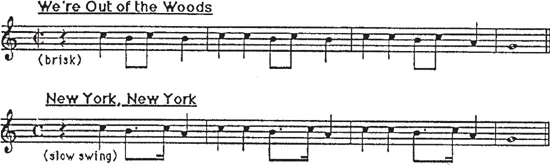

The thread of cultural influence is often spun so fine that observers can lose sight of it. Consider a song like “New York, New York,” which Mayor Ed Koch declared the city’s “official song” in 1985. Most people have already forgotten that John Kander originally wrote it for Judy Garland’s daughter, Liza Minelli, who played a young, up-and-coming swing-band singer in the 1977 film of the same name. As it turns out, the film is full of allusions to Garland,1 and one of the most surprising but hitherto unremarked of these allusions appears in the principal theme of the title song itself. Fans of Garland’s most famous film, The Wizard of Oz (1939), will recall that at the moment when Dorothy and her friends leave the deadly poppy field and begin skipping up the Yellow Brick Road toward the Emerald City, radiant in the distance, a tune is sung off-screen by “The Rhythmettes”: “You’re out of the woods, you’re out of the dark, you’re out of the night … step into the sun, step into the light …” This melody, when slowed down to a swinging adagio, becomes the opening bars of “New York, New York.” Figure 1.1 shows what the two passages of music look like when written out, both transposed to the key of C.

Kander’s choice of melody for his title song, so expressive of Minelli’s upbeat, starry-eyed excitement at being “a part of it,” not only echoes, almost note for note, the score of the film that first made Minelli’s mother famous, but echoes that unique passage (it is not repeated elsewhere in the film) when Dorothy Gale beholds the urban goal of her perilous pilgrimage, the Big City where her desires will, supposedly, be fulfilled. Though the borrowing may have been unconscious,2 it makes perfect sense. MGM took L Frank Baum’s turn-of-the-century fantasy and made it into a parable of the “fanzine” Hollywood or Broadway success story: small-town or, better, farm girl—from Kansas, let’s say—comes to the Big City with practically nothing but the clothes on her back and finds a big-name “producer”—a humbug and a snake-oil salesman like all the rest, but a great manager of illusions, a great purveyor of dreams. Under his direction, she achieves fame and glory, sees her name, not just in lights, but written on the sky, and becomes the idol of millions.

Fig. 1.1 Opening bars of “You’re out of the woods” and “New York, New York.”

Tracing the origins of “New York, New York,” we arrive in Oz, where we discover an ancient archetype—the quest—resurrected in a distinctly modern feminine form. It is the archetypal power of this feminine quest saga, in fact, that makes the identification of Garland with her role as Dorothy Gale so compelling, and that enables us, in turn, to make sense of the curious derivation of her daughter’s hit song. Garland, after all, went on to embody the Tinsel-Town version of the female quest in later movies like A Star is Born (1954) and the less successful I Could Go on Singing (1962),3 and to live the tragic denouement of the Hollywood success story herself. One of the most important features of this modern female version of the quest archetype is the Big City, a place mythically associated since antiquity—for example, Plato’s Atlantis, John’s New Jerusalem, Augustine’s City of God, and More’s Utopia—with ideal self-fulfillment, apocalyptic transformations, and apotheosis.4 Hollywood and New York epitomize the Big City as the mythical site of heroic struggle and triumph for the modern woman. They have become, as much as the Emerald City itself, pieces of mythical American real estate, urban sites in our collective consciousness.

Figuring prominently and repeatedly since the late nineteenth century in American tales and movies about female success, the Big City soon came to embody ambivalent American attitudes toward women who were trying to “make it” in a man’s world, that is, a world removed from the demands traditionally placed on women in their familial roles as obedient daughters and nurturing wives and mothers. These attitudes, in turn, were rooted in turn-of-the-century urban culture. Baum conceived his spunky, city-bound young heroine during the years that saw the emergence on the urban scene of a radically modern and untraditional image of femininity, the “New Woman.” The social and economic forces that were creating the modern American cityscape—the acceleration of industrialism, the growth of capital investment and employment opportunities, the spread of the railroads—were also opening up new opportunities for young women.5 They were leaving their families behind on the dusty prairies and in the small towns of depressed rural America and going where the new jobs—as salesgirls, garment workers, waitresses, typists, and journalists—offered them the chance of realizing the American dream of financial and familial independence.6 The archetype of Big City fulfillment was becoming feminized by the appearance of these “New Women,” a phenomenon, as Albert Auster (5) has noted, that was disturbing traditional notions of a woman’s “proper” relationship to men and marriage. Insofar as it represented the field of feminine, as opposed to masculine, ambitions, however, the American myth of Big City opportunity soon revealed an ironic tendency to reaffirm domestic values at the expense of personal fulfillment.

In no urban profession at the turn of the century was the promise of liberation from the traditional economic, social, and familial constraints on women more appealing and more pronounced than in the theater, which at that time was flourishing in the urban economic boom. Big-name actresses, after all, had the financial independence, the exotic, glamorous aura, and the mass popularity to allow them to reject the traditional roles of housewife and mother with little harm to their standing in the eyes of society, or to their professional careers. It was only to be expected, given the exigencies of theater life—extended separations, constant traveling, long hours—that the infidelity and divorce rates among actresses, like their incomes, should be much higher than the norm. Not surprisingly, actresses were among the staunchest and most visible supporters of the resurgent feminist and suffragist movements of the 1890s and early twentieth century.

The actress’s power as feminist spokesperson and exemplary New Woman was strengthened by the fact that, in the earliest instances of exactly the phenomenon which has made MGM’s Oz so popular with fans of Judy Garland, theatergoers were beginning to identify more with the actress than with the role (usually quite conventionally feminine) that she played. The 1890s and the first decade of the new century saw the appearance on the American stage of the modern “star” system and so-called “personality school” of acting, which encouraged “the substitution of the performer’s personality for the dramatic character, or the portrayal of dramatic characters which fit the performer’s personality so exactly that performer and character [were] practically identical” (Wilson, 269).

Complementing and encouraging the rise of the star system and personality school was the “matinee girl” phenomenon: young working women, usually teenagers, would attend Saturday matinee performances unescorted in order to see their favorite “matinee idols.” Edward Bok, editor of Ladies Home Journal, is quoted by Albert Auster as deploring the matinee girls’ attendance at adult plays: “One will see at these matinees seats and boxes full of sweet young girls ranging from twelve to sixteen years of age. They are not there by the few, but literally by the hundreds” (Auster, 39). Theodore Dreiser’s fictional stage-struck heroine, Carrie Meeber, in Sister Carrie, discovers during her first encounter with big-city theater a world “complete with wealth, mobility, and … independence” (Dreiser, 166). What was drawing young women to the theaters was no longer just the character the actress played, but the popular image of the actress herself—she was becoming her own heroine, and the story of her successful liberation from the trammels of domestic drudgery was becoming the central myth by which a new generation of women defined their own hopes and aspirations.7

Sister Carrie is a particularly interesting illustration of the Big City theatrical success story. It is a work, oddly enough, exactly contemporary with Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz—both were published in 1900—and sharing the feminized quest-theme. Carrie Meeber, like Dorothy Gale, travels from the rural areas of the great Midwest to find her dreams fulfilled in the burgeoning metropolis that served as Baum’s model for the “Emerald City,” Chicago. Like the real Judy Garland, Dorothy’s later film incarnation, Carrie is intent on becoming a famous performer, and like Minelli, she ends up “making it” in New York, on Broadway, while her lover Hurstwood, the prominent, rich, and very married saloon-keeper with whom she elopes from Chicago, ends up dying penniless in a flop-house on the Bowery. In this respect, Sister Carrie eerily anticipates A Star is Born as well, where the female star’s already famous actor-husband, played by James Mason, slowly sinks into despair and finally drowns himself as his wife’s fortunes rise.

But despite their mythic similarities, Dreiser’s tale and Baum’s differ in one important respect. For while Carrie is traveling to Chicago to make a successful and independent life for herself away from home, Dorothy is traveling to the Emerald City—defying “lions and tigers and bears” and overcoming the perils of the poppy field—in order to return home. One might even suggest that our full enjoyment of the trials and triumphs of Dorothy’s quest can only be sustained insofar as we manage to forget that her ultimate goal, unlike that of most male heroes, is not to achieve the complete independence of an adult, but to return to the secure dependency of childhood. The twice-repeated last line of the film supplies its moral—“There’s no place like home!”8 To this extent, Baum’s otherwise plucky heroine and her adventures in Oz reflect the covert, and sometimes quite overt, antagonism of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century writers toward independent women, not only as represented in literature by men, but in stories of female entrapment and renunciation written by independent women writers themselves. The works of Sarah Orne Jewett, Edith Wharton, Kate Chopin, and Willa Cather all offer examples of late nineteenth-century heroines who, setting out to fulfill themselves in a male-dominated society, either surrender their independence to a man or give up the struggle altogether, outcomes terribly ironic in light of their creators’ quite independent and self-reliant lives as woman writers and editors in a male-dominated profession.9

Far worse, however, than such images of self-defeat penned by women writers were popular representations of the “New Woman” by outspokenly anti-feminist and anti-suffragist male writers like Robert Herrick. Herrick’s New Women are invariably portrayed as leading empty, unfulfilling, and melancholy lives because they refuse to tend to their proper domain: home, hearth, and husband. The female, for Herrick, is in her element—and truly happy—only as housewife, social ornament, and domestic cheerleader for the man of the house, who must go out each day and fight for survival like any other predator, or prey, in the vast economic and political jungle of social Darwinism. For Herrick, the city represents the mythic scene, not of woman’s liberation from, but of her fulfillment in her proper sphere, social and domestic. Consider, for instance, the almost fairy-tale nuances of the following description of the Manhattan skyline in Herrick’s book Together: “‘I love it!’ murmured Isabelle, her eyes fastened on the serried walls about the end of the island. ‘I shall never forget when I saw it as a child, the first time. It was a mystery, like a story-book then, and it has been the same ever since’” (311). “Thus,” intones Herrick, “the great city—the city of her ambitions—sank mistily on the horizon” (312; Isabelle is sailing to Europe). It’s a description worthy of Oz—or of Hollywood. But Isabelle’s great ambition is to become the most prominent hostess in the New York Social Register. Her idea of “making it” is entirely, and approvingly, domesticated.

Unhappiness and disappointment are, Herrick implies, the just punishment New Women bring on themselves for their unnatural feminist tendencies. Such punitive characterizations make all the more clear the reasons for the vituperation heaped on Dreiser with the publication of Sister Carrie, which so blatantly contradicted the mythical stereotype. The glamorous success of Dreiser’s easy-going, self-infatuated, ambitious, and amoral (if not immoral) young heroine violated every canon of American-Victorian poetic justice. Carrie never had to pay for flouting the conventional idea of femininity. Dorothy did—or at least, she had to make her token bow to the demands of domesticity. And in the movie it is even worse: the heroine’s quest to prove her fitness to take on the wide world of adulthood is shown, in the end, to have been a dream all along. Her literally “real” place is at home.

Of course, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is hardly an anti-feminist tract, even though in some of his other children’s books Baum did satirize the suffragists and their supporters. (As Moore points out, his mother-in-law, Mathilda Joslyn Gage, was a close friend of Susan B Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton and a well-known suffragist polemicist in her own right [50–51].) Baum’s book simply reflects the prevailing notion that little girls should stay at home. But because Dorothy is no ordinary little girl, the book’s final capitulation to prevailing notions is not an ordinary concession. Dorothy was the first true American counterpart to Lewis Carroll’s independent-minded and matter-of-fact Alice,10 and as such, she posed a threat to established American notions of youthful female propriety, as the early history of her banishment from many library bookshelves testifies. Even though, like her English cousin, Dorothy is safely and permanently pre-adolescent, which would make her independence generally non-threatening to adult males,11 Baum watered down much of the delightful matter-of-factness and unselfconscious courage of his heroine in later Oz books, as though shocked, on second thought, by the unladylike qualities of his own creation. Raylyn Moore notes with dismay “the overweening sentimentality about young females which infiltrates the later Oz books” (133), how from Ozma on Dorothy becomes “increasingly ‘cute,’ even coy” (155), eliding syllables in her speech (“s’pose” for “suppose,” “‘cause” for “because”), acting “skittish” and “irritable,” more and more like “the kind of girls who shy at spiders” (156).

Or like the kind of girls who should have stayed at home. It is, in fact, just that little-girl quality of vulnerability and, in the end, lack of self-confidence that cripples the rising star of the Garland legend with self-disesteem and remorse.12 Under all the spunky independence, courage, loyalty, and practicality beats a heart longing for the comforts of home and family, Uncle Henry and Auntie Em. (To give Baum some credit, he never makes Dorothy’s home look very attractive.) That is the flip-side of the Big City myth of feminine success and freedom: in her rise to fame the star loses family, old friends, affection—she loses touch with “home,” the locus of her “true” (which means conventionally female) self. In the end she will come to regret it—the ingénue of “A Star is Born” will probably end up, long after James Mason has walked out of her life and into the surf, on Sunset Boulevard rooming with Gloria Swanson, where she will have nothing to console her but memories of faded glory and glamour: no husband, no children, no happy family ending.

The Hollywood realities of female cinematic success, however, like those of Big-City female theatrical success at the turn of the century, have always been at odds with t...