- 408 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The World Wide Web is truly astounding. It has changed the way we interact, learn and innovate. It is the largest sociotechnical system humankind has created and is advancing at a pace that leaves most in awe. It is an unavoidable fact that the future of the world is now inextricably linked to the future of the Web. Almost every day it appears to change, to get better and increase its hold on us. For all this we are starting to see underlying stability emerge. The way that Web sites rank in terms of popularity, for example, appears to follow laws with which we are familiar. What is fascinating is that these laws were first discovered, not in fields like computer science or information technology, but in what we regard as more fundamental disciplines like biology, physics and mathematics. Consequently the Web, although synthetic at its surface, seems to be quite 'natural' deeper down, and one of the driving aims of the new field of Web Science is to discover how far down such 'naturalness' goes. If the Web is natural to its core, that raises some fundamental questions. It forces us, for example, to ask if the central properties of the Web might be more elemental than the truths we cling to from our understandings of the physical world. In essence, it demands that we question the very nature of information. Understanding Information and Computation is about such questions and one possible route to potentially mind-blowing answers.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, divide the work, and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.

Antoine de Saint-Exupery

One balmy summer’s night, when the sky is clear and the smell of freshly cut grass hangs heavy in the warm still air, take time out, find a calm open space and gaze up at the stars. What do you see? As you take in the vista of shimmering dots that glisten in the blackness of space, surely you see beauty? Surely you see the majesty of the universe before you? If you do, then you are not alone. Ever since man could look up at the stars, others have marvelled at such beauty and some have even dared to question why it should be so. From such curiosity came the very essence of science itself.

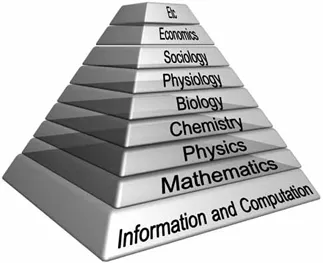

The attention of physics is entirely focused on the universe and all it contains, as it tries to understand the very most fundamental workings of all we perceive as real. But physics is not an island. It is not self-sufficient when it comes to the tools needed to explain what it seeks to describe. In particular, physics carries a high reliance on mathematics and uses it as the predominant language through which it chooses to speak. So tight is this relationship that we can consider mathematics to be the bedrock on which physics is placed, the very foundation from which our deepest understandings of the universe are built. But there are still deeper foundations. Mathematics itself is based on the concept of individuality and the ability to group such individualities together into more useful concepts. From this the familiar concepts of numbers, arithmetic, geometry and algebra are created and today we put them to work with a high degree of success.

For most who care to consider such matters, that’s it, dig down to the very base of mathematics and the roots go no further. Once it is understood where the basic building blocks come from, there is nothing below. But what if there was something below, something holding up numbers, all other mathematical concepts and all the various fields of science above that too? If that were the case then surely that something must be the real stuff from which the universe is made? Surely that something must represent the very signature of everything itself?

In recent times the ideas behind information and computation have seen their profile rise and with the advent of technologies like the Internet and the World Wide Web it’s not hard to see why. Yet most still see information technology and its near relation computer science as resting on top of physics and mathematics. We even have fundamental models of computation that clearly line up with fundamental physical models such as quantum mechanics. But what if we chose, for some rebellious reason, to turn the whole model on its head? What if we chose to suggest that physics and mathematics were founded on the notions of computation and information; numbers, arithmetic, algebra, quantum mechanics … everything?

Most contemporary scientists would wince at the proposition of mathematics not being fundamental, but there are a growing few who would not. Ask your everyday scientist where information and computing should sit in the stack of scientific disciplines and they will most likely respond with confusion. Perhaps above sociology and economics, they might suggest, going on to say that entities like the Web are clearly propped up by such things. But there are those who think differently. To them the universe is just one gigantic computer system feeding on its own information and changing in ways we choose to consider as the reality around us.

Figure 1.1 Where in science should information and computation sit?

Figure 1.2 Information and computation as the bedrock of all other sciences

The World Wide Web is a truly remarkable innovation. For large sections of this planet’s population it now touches our lives through a veritable explosion of change. Some influences are obvious, like the personal knowledge gained from basic Web browsing, but many are not so apparent. For instance we now see extreme cases far removed from the interactions we might traditionally consider as normal within our global society’s fabric. These predominantly relate to the vast collection of autonomous Web software now chattering away in the background of our existence. Many refer to the components of this intertwined mesh as collaborating Web services, but this is really a generalisation that has become quickly outmoded. What is profoundly relevant, however, is that the world around these components has changed in recent times and a tipping point has been reached beyond which can be found an automated and intelligent environment hitherto beyond mankind’s reach.

Why should this be so? The answer cannot so much be found with the software itself, or not at least if we are happy to consider such software one instance at a time. Rather it comes from the increasingly complex mesh of software-upon-software, computation-upon-computation and information-upon-information into which each individual component is now being placed. From this diverse mixture of connectivity an emergent property may now be starting to rise. This is the swarm intelligence of the Web; the common interpretation of its emergence is predominantly technical. But the Web is not wholly technical. The intention behind its inception may well have been so, but today it has evolved into a complex sociotechnical machine that is radically different. To characterise the modern Web as anything other than a global fusion of society, computation and information would be to do it an injustice. It is simply the largest human information construct in history. Furthermore the emphasis must be on ‘machine’ here, as evidence exists in support of the Web as a computational device in its own right, independent of the skeletal support donated by its underlying Internet. This changes the game for Web-based software as it acts like molecules in an overall system of much richer, more natural, design.

This string of analogies in connection with the Web is used for deliberate reason, as current research points to the relevance of thinking taken from the physical sciences. In particular the areas of quantum mechanics and relativity stand out as holding particular promise. This implies a number of unfamiliar consequences for those who wish to understand the next generation of the Weblike systems. It also offers great promise for those who work in the classical sciences. Not only is the Web the largest synthetic system humankind has every created, but it also provides the largest sample set of data in existence, outside the informational mass of the very universe itself. If this could be, or more likely when it is, analysed across its full breadth and depth, the chances are high that new types of complex geometries, patterns and trends will be found. The search will then be on to investigate if fundamental laws are at play in their formation and how these might relate to other fundamental laws already known.

It is already established fact, for instance, that the quantum model of computation has greatly strengthened our very understanding of what computation is. So it is plausible to suggest that thinking from physics’ other great school of thought – that of the relativists – might also contribute in a similarly profound way. In fact, both physics and computing have already embraced the essence of relativity as a general underlying principle in many of their most fundamental models, the physicists commonly referring to it as ‘background-independence’[14] and computer scientists favouring the term ‘context-free’.[15] What Albert Einstein taught us was that at larger scales the differences between observable phenomena are not intrinsic to the phenomena but are due entirely to the necessity of describing the phenomena from the viewpoint of the observer.[6] Furthermore in the 1960s a different explanation of relativity was proposed, positing that the differences between unified phenomena were contingent, but not because of the viewpoint of a particular observer. Instead physicists made what seems to be an elementary observation: a given phenomenon can appear different because it may have a symmetry that is not respected by all the features of the context(s) to which it applies – an idea that gave rise to gauge theory in quantum physics. This only helps to suggest that if quantum mechanics presents a fundamental model of the universe[48] which should in turn, one day, be unified with other fundamental models of the universe, such as relativity, then perhaps the most fundamental models of computation are yet to come.

Those who subscribe to the quantum school of computation also freely align with the idea that the laws of quantum mechanics are responsible for the emergence of detail and structure in the universe.[21] They further openly consider the history of the universe to be one ongoing quantum computation[21] expressed via a language which consists of the laws of physics and their chemical and biological consequences. The laws of general relativity additionally state that at higher orders of scale, the complexity and connectivity of the physical fabric of the universe must be seen as curved and not straight, physical – space itself being considered as simply a warped1 field through its most fundamental definition. Indeed the geometry of space is almost the same as a gravitational field.[2] All of this points to an alternative way of looking at reality, a way that relies on distinctly different geometries to the straight line variants with which we are generally familiar. In many ways too, mainstream theories of computation also need a refresh of perspective and history tells us not to be worried too much about such matters. Geometry suffered its own crisis long before computing. In 1817 one of the most eminent mathematicians of the day, Carl Friedrich Gauss, became convinced that the fifth of Euclid’s2 axioms3 was independent of the other four and not self-evident, so he began to study the consequences of dropping it. However, even Gauss was too fearful of the reactions of the rest of the mathematical community to publish this result. Eight years later János Bolyai published his independent work on the study of geometry without Euclid’s fifth axiom and generated a storm of controversy which lasted many years. His work was considered to be in obvious breach of the real-world geometry that the mathematics sought to model and thus an unnecessary and fanciful exercise. Nonetheless, the new generalised geometry, of which Euclidean geometry is now understood to be a special case, gathered a following and led to many new ideas and results. In 1915, Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity suggested that the geometry of our universe4 is indeed non-Euclidean and was supported by much experimental evidence. The non-Euclidean geometry of our universe must now be taken into account in both the calculations of theoretical physics and those of a taxi’s global positioning system.[16][99][100][101] This drives the point that what is naturally instinctive is not always right.

More on the Web and a Brief History

Might the Web provide a way to the change of perspective sought in computation? In order to start to answer this question we must first further clarify what the Web is not. It is not, for instance, the Internet, although it is dependent upon it. The two are sometimes perceived as synonymous, but they are not.[2] For this reason any use of the colloquialisms like ‘the Net’ in reference to the Web can only serve to confuse and hence should be frowned upon. The Internet is a communications network, a global framework of wires, routing devices and computers on which the Web rests, and to think of the Web just in terms of electronics and silicon would be wrong. Other terms like ‘Information Super Highway’ may also be easily misconstrued as characterising the Web but don’t really quite get there. They do not convey the truly global, interconnected nature of its vast information bank, instead perhaps conjuring up unnecessarily images, heavily dependent on microprocessors and tin.

The Web is not as youthful as one might first think either. Computing pioneer Vannevar Bush outlined the Web’s core idea, hyperlinked pages, back in 1945, making it a veritable old man of a concept on the timescale of modern computing. The word ‘hypertext’ was also originally coined by Ted Nelson in 1963, and can be first found in print in a college newspaper article about a lecture he gave called ‘Computers, Creativity, and the Nature of the Written Word’ in January, 1965. That year Nelson also tried to implement a version of Bush’s original vision, but had little success connecting digital bits on a useful scale. His efforts were hence known only to an isolated group of disciples. Few of the hackers writing code for the emerging Web in the 1990s knew about Nelson or his hyperlinked dream machine, but it is nonetheless appropriate to give credit where credit is due. From such beginnings, the origins of the Web as we would begin recognise it today eventually materialised in 1980, when Tim Berners-Lee and Robert Cailliau built a system called ENQUIRE – referring to Enquire Within upon Everything, a book Berners-Lee recalled from his youth. While it was rather different from the Web we see today, it contained many of the same core ideas.

It was not until March 1989, however, that Berners-Lee wrote Information Management: A Proposal, while working at CERN, which referenced ENQUIRE and described a more elaborate information management system. He published a formal proposal for what would become the actual World Wide Web on 12 November 1990 and started implementation the very next day by writing the first Web page. During the Christmas holiday of that year, Berners-Lee built all the tools necessary for a working Web in the form of the first Web browser, which was a Web editor as well, and the first Web server. In August 1991, he posted a short summary of the World Wide Web project on the alt.hypertext newsgroup. This date also marked the debut of the Web as a publicly available service on the Internet. In April 1993, CERN finally announced that the World Wide Web would be free to anyone, with no fees due – and the rest, as they say, is history. The Web quickly gained critical mass with the 1993 release of the graphical Mosaic web browser by the National Centre for Supercomputing Applications which was developed by Marc Andreessen and Eric Bina. This again was a seminal event as prior to the release of Mosaic, the Web was text-based and its popularity was less than older protocols in use over the Internet. Mosaic’s graphical user interface swept all that aside and allowed the Web to become by far and away the most popular protocol in use.

In more recent times it has become indisputable that the Web is having an increasingly profound impact on the way that we, as individuals and social groups, go about our everyday lives. But regardless we should not forget that it is only one integral part in humanity’s ever-growing ability to create and process information. Putting the Web into this wider context, an impressive picture is painted, as the much credited ‘didyouknow’ presentation at www.shifthappens.com helps to explain:

• There are over 2.7 billion searches performed on Google each month.

• The number of text messages sent and received every day exceeds the population of the planet.

• More than 3,000 new books are published every single day.

• It is estimated that 1.5 exabytes (1.5 × 1,018) of unique new information were generated in 2007. That’s estimated to be more than in the previous 5,000 years.

• Predictions are that by 2013 a supercomputer will be built that exceeds the computation capability of the human brain.

• Predictions are that by 2049 a $1,000 computer will exceed the computational capabilities of the human race.

Such statistics are indeed impressive, but pointing out an exponential growth in information and our appetite to consume it is simply not enough. To appreciate the full picture, the great sea-change under way in our population’s demographic must also be understood. In the 400 years from 1500 to 1900, the human population of this planet increased at an average rate of just fewer than 3 million people per year. However, in the 100 years from 1900 to 2000, the average yearly increase grew to 44 million – nearly a 15-fold increase. So by such reckoning some calculations stat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword by Yorick Wilks

- Foreword by L.J. Rich

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Dot-to-Dots Point the Way

- Chapter 3 Hitler, Turing and Quantum Mechanics

- Chapter 4 A Different Perspective on Numbers, Straight Lines and Other Such Mathematical Curiosities

- Chapter 5 Twists, Turns and Nature’s Preference for Curves

- Chapter 6 Curves of Curves

- Chapter 7 To Process or Not?

- Chapter 8 Information and Computation as a Field

- Chapter 9 Why Are Conic Sections Important?

- Chapter 10 The Gifts that Newton Gave, Turing Opened and Which No Chapter One Has Really Appreciated Yet

- Chapter 11 Einstein’s Torch Bearers

- Chapter 12 Special Relativity

- Chapter 13 General Relativity

- Chapter 14 Beyond the Fourth Dimension

- Chapter 15 Time to Reformulate with a Little Help from Information Retrieval Research

- Chapter 16 Supporting Evidence

- Chapter 17 Where Does This Get Us?

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding Information and Computation by Philip Tetlow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.