- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Developed countries throughout the world are experiencing population ageing and the new challenges that arise from this change in the national demographic. The phenomenon of an ageing population has necessitated policy reform regarding the role of the state in providing income in retirement and the whole wider social meaning of later life. The politics of ageing have become a key issue for young and old voters alike as well as those who seek to represent them. Politicians carefully consider strategies for developing relationships with older voters in the context of both policy decisions and campaigns as issues that directly affect an ageing population often prove crucial in local and national election campaigns. 'Going Grey' provides insight into how ageing and the increased proportion of older voters is being framed by the media. It investigates emerging discourses on the topic founded on economic pessimism and predictions of inter-generational conflict. By bringing together political communication and media discourses and placing them within the wider context of an ageist society this unique contribution demands us to re-think how the media portray and frame later life and examines the strategic electoral dilemmas facing political parties today. It provides an original and timely resource for scholars, students and general readers interested in understanding more about the mediation of, and the strategic campaign responses to, rapidly ageing populations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Going Grey by Scott Davidson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Societies across the globe are experiencing rapid population ageing. Life expectancy in Great Britain is increasing at more than five hours a day and will continue to do so, at least into the medium-term future (Academy of Medical Sciences 2009). By the middle of the twenty-first century society will have an age composition never seen before in human history. In the 1880s just over 7 per cent of the population was aged over 60, similar to estimates of the sixteenth century but, lower than estimates of the proportion of older people in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. By the 1980s this proportion had incrementally crept up to 17 per cent, and over the past 50 years the population of the UK has aged considerably. While the proportion aged under 16 has decreased from 24 per cent to 20 per cent, the population aged over 60 has increased from 16 per cent to 21 per cent (Thane 2000). The ageing process will accelerate over the coming decades. Ageing will also apply to the working age population which will become much older as the baby boom generations of the mid 1960s age. According to the Government Actuary’s Department (GAD) there were 1.7 million (10 per cent) more working age adults aged below 40 than were aged 40 and above in 2006. By 2020, as a result of the equalisation and increase in women’s state pension age, there will be more working adults aged 40 and above than below 40. With further increases to the state pension age for both men and women there are projected to be 1.4 million (7 per cent) more working age people above 40 than below 40 (GAD 2008).

As a societal trend population ageing has some way to go before levelling off. The electorate that chooses the government of the day is ageing. The rise of the ‘grey vote’ is already apparent at the start of the twenty-first century, but by the middle of the century it will have reached dramatic proportions. A key component in the future growth of the grey vote will be the fast approaching retirement of the baby boomer cohorts. The boomers have been identified by a number of commentators as significant, not just for their weight of numbers, but for their qualitatively different characteristics as a cohort. The boomers are seen as possessing higher expectations of consumer and public services which will translate in political action with the necessary political reforms (Churchill and Mitchell 2004).

The demographic age-transition of British society raises many questions and holds a myriad of policy implications that are not limited to bread and butter ageing issues such as pensions, health and social care, but also ranges across family policy, the labour market and cultural change. As a significant element to its approach, this book has chosen to focus upon the challenges facing political parties and their communications and election campaigns. We live in what is sometimes described as a youth-obsessed society where only in the recent past one of the major parties of government, in the shape of the Labour party, re-branded itself as the ‘new’ against the ‘old’, with its then leader Tony Blair making the case for his party in a book entitled My Vision of a Young Country. The country may be experiencing an age transformation, but in the 1990s at least it was still possible to develop a political brand in juxtaposition against the old. Only two decades later it must be questionable how tenable it would be for a major party to run against the demographic characteristics of the voters.

To study the changes that population ageing heralds for political communication it is also necessary to evaluate how the mass media are reporting and framing the implications of ageing. The extent to which media effects alter and influence political behaviour remains controversial and complex, however, even if the weight of evidence were to come down on the side of minimal impact on social attitudes, media content would still matter because the political elite believe in media effects and evaluate media content on a daily, sometimes hourly, basis (Gould 1999, Jones 2000, Rawnsley 2000, Barnett and Gaber 2001).

It is neither feasible nor desirable in any major study of this nature to attempt to separate the behaviour and story narratives of the media from party communications. This book accepts the arguments that the disciplines of political marketing – the use of opinion research and environmental analysis to produce and promote a competitive offering which will help realise organisational aims and satisfy groups of electors in exchange for their votes (Wring 1997) – as an increasingly useful model for explaining the behaviour of parties. Political parties that seek power need to achieve significant national vote (or market) shares to realise their basic strategic goals, but in the near future this market share cannot practically be obtained unless they obtain the polling endorsement of large numbers of older voters. The changes in communication content and style required to successfully campaign for grey votes will be delayed by the levels of residual ageism and the old orthodoxies of marketing and advertising practitioners who fear the implications of any brand being too closely associated with ‘the old’. But, ultimately we should expect parties to act rationally and not deny themselves power by perversely clinging to attitudes from a previous era.

Our political imaginations and debates are often infused with impressions of the defining demographic characteristics of the parliamentary seats that are contested so keenly by the parties seeking power. Currently, these impressions when applied to constituencies such as Scarborough or Torbay may elicit images of pleasant coastal towns, but they are just as likely to be along the lines of The Guardian newspaper’s online constituency profile of Torbay ‘… sunny southwest coast resort with many pensioners’ (Guardian Online, accessed January 2012). Scarborough or Torbay may often be defined by their large retired populations, but, as will be seen in Chapter 10, in 20 years’ time seats in the Rhondda, Bootle, Basildon and Sunderland will have the same, or indeed, older, age profiles than the Torbay of today. The next general elections as we move into the 2020s will take place in the middle of an age transformation of British society and by 2025 the electoral destiny of most parliamentary seats will be settled by older voters who will cast, as this book will demonstrate, over 50 per cent of votes on polling day. Yet, debate on the inexorable rise of the grey vote has been strangely muted despite the ever widening age gap in turnout, the sheer weight of numbers, and the emergence of a Labour-Conservative ‘Grey Battleground’.

Strategic reorientation toward the greying electorate may be a slow process but the growing ranks of the retired have been apparent for some years and the changing age profile is seemingly bound to influence the conduct of politics however, it has been the recent and dramatic drops in turnout amongst younger age groups which has served to both accelerate and exaggerate the impact of population ageing. Data from the British Election Study suggests the stark differences in voter turnout between age groups was not a factor until after the 1992 general election (Clarke et al. 2004). Younger age groups in the 1970s showed lower turnout rates, but in subsequent elections their turnout increased bringing them into line with the wider electorate. But, this trend seems to have been broken in the 1990s, with voters that joined the electorate in this period holding onto their lower propensities to vote and are considerably more susceptible to forces that are working to suppress electoral turnout. A natural assumption to make might have been that the historically low turnout rates for first-time voters in 2001 would increase in 2005 and 2010 in line with the increase in overall turnout, yet it appears turnout rates for voters aged 18–24 dropped further in 2005 and turnout in the 25–34 age band stood still (Phelps 2005). This raises the prospect that these cohorts will always have participation rates below those of previous generations – locking in and accelerating the age transition of the electoral market.

The burgeoning ranks of older voters pose a number of important questions on the current and future interactions between public policy and the electoral cycle based solely on consideration of people who have passed the state retirement ages. However, to fully evaluate the age effect on the democratic process there is a persuasive argument that the definition of the ‘grey vote’ should be widened to include segments of the electorate who are close to retirement and indeed perhaps to all men and women aged over 50. The inclusion of the over 50s can be justified on several grounds. Firstly, people in their 50s start to personally experience the many manifestations of age discrimination in society, most critically in employment where the proportion of British males aged 55–64 who were in employment has fallen from 80 per cent in 1979 to 62 per cent in 2002 (Humphrey et al. 2003). Secondly, the over 50s have reached a stage in their life courses where they have to consider retirement and ‘old age’ as issues requiring practical, sometimes urgent, personal attention. Voters who are nearing retirement will be acutely aware of any inadequacies or inequities in the pensions system. Finally, the family structure of many over 50s is likely to include parents who will be in their 70s or 80s further heightening awareness of the quality, or lack of quality in health and social care. For many, acting on behalf of relatives who require long-term care can become a discouraging experience.

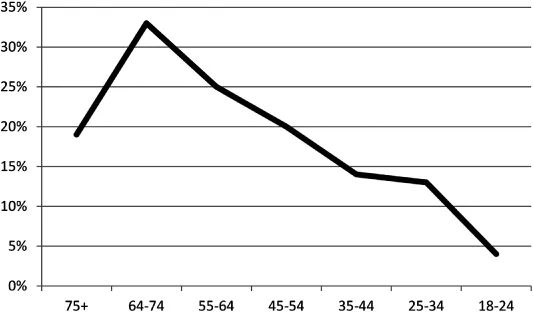

The significance of the changes reaches beyond numbers. Older people have been shown to have higher levels of engagement with civic society and the democratic process. We already know that younger people are less likely to vote in general elections than those aged 55 and over, those aged over 55 are also the most likely to have voted in a recent local council election, 70 per cent in comparison to 39 per cent of 18–34 year olds. Older people are also much more personally active in legislative politics with 33 per cent of 65–74 years olds claiming to have contacted their local councillor or MP on an issue, in comparison to 13 per cent of 25–34 years olds, and perhaps unsurprisingly only 4 per cent of 18–24 year olds have claimed to have done so (Hansard Society 2011). Older volunteers are also largely responsible for maintaining the grassroots organisation of the major political parties (Seyd and Whiteley 1992). Nor is the activism of older people strictly confided to traditional politics. Pensioners are more likely to be consumer activists than young people. But, it is the baby boomers who are most likely to be consumer activists. A study for the National Consumers Council which investigated levels of consumer activism through participation in a range of typical activist activities found that boomers were the most likely to have taken part in at least five of these activities in the preceding 12 months (National Consumers Council 2002).

Within this demographic context some writers have begun to believe that the grey lobby will grow ever more powerful and difficult to ignore. Some such as Lloyd (2002) argue that the UK is beginning to reflect US politics where the American Association of Retired Persons has been described as a larger and more powerful lobby than organised labour. Some respected theorists and prominent writers such as Sinn and Uebelmesser (2002) and Dychtwald (1999) go as far as predicting ageing democracies such as Germany and the USA will become ‘gerontocracies’ within the next five years. Evidence suggests that in the USA at least, candidates and campaigns target senior voters more than other age groups (MacManus 2000). While the 2004 presidential election campaign saw a large increase in the number of political adverts on television that addressed the concerns of older voters (Kaid and Garner 2004).

Figure 1.1 Percentage of respondents by age group who have contacted a local councillor or MP in the last two to three years

Source: Hansard Society 2011.

Demographic trends in combination with the increasing use of segmentation have influenced the tone of debate on population ageing. Implicit in concerns of imminent gerontocracy is a senior power model for predicting the impact of the politics of ageing. The senior power model is based on the assumption – derived from applying economic theories to politics – that older voters are likely to vote to secure or improve their material self-interests. The model also assumes that older voters perceive their interests in social security and pensions similarly and that because of this material self-interest older people are homogeneous in political attitudes and voting behaviour and will inevitably come into conflict with younger age groups in the electoral process (Davidson and Binstock 2011).

For other writers the situation is more paradoxical, a case of ‘large numbers but small influence’ excluded from political influence by the consequences of their exit from the workplace (Walker 1996, with ‘little evidence of increased responsiveness by governments or political parties to organised groups of older people’ (Vincent et al. 2001). Yet, the very fact that informed opinion can be divided on this issue demonstrates how radically different the debate on the electoral importance of older people is now in comparison to only two decades ago. In 1982 in one book that was to become a frequently cited work within the field of social gerontology Chris Phillipson was writing:

This book has been written in a period of crisis for elderly people. Health and social services are being substantially reduced; questions are being raised about the ability of society fully to protect pensioners against price increases; older workers are urged to retire as soon as possible as a means of reducing high unemployment amongst young people. (Phillipson 1982)

In the first decade of the twenty-first century some core elements of Phillipson’s prognosis of crisis in the welfare of older people have been turned on their head. Health and social care spending have increased considerably and considerable efforts are being made by governments across the globe to keep older workers in the labour force as well as striving to find public consent for rises in state pension and public sector pension retirement ages.

Nonetheless, many of the senior power model’s assumptions are contradicted by recent trends despite discernible efforts to target older voters on issues related to welfare and pensions, evidence from the USA has shown little impact on electoral choices across age groups. Age is only one personal characteristic of older voters with which they may identify themselves and older cohorts are diverse in terms of gender, ethnicity, religion, education, health, family status, geography and political affinity. Furthermore, seniors are voting for candidates who usually represent parties who have a broad range of policies and issue position of which pensions is only one (Campbell and Binstock 2011).

The evolution of a new politics sponsored by the profound demographic changes will not take place without the input and influence of the media. The mass media holds a special role in its ability to set public policy agendas. This agenda setting ability has been noted in a number of publications, such as Franklin (1994) and his notion of ‘media democracy’ as well as McQuail (2000) and Eldridge et al. (1997). As will be seen in Chapter 6 the media have been accused by a wide range of researchers of predominantly portraying older people using negative stereotypes and for framing older people as a burden on society as a whole. The stereotyping remains a constant in much media coverage of older people, but many journalists also subscribe to the aims of the third age movement which is attempting to reconstruct the meaning of later life as an opportunity rather than a problem. The negative media content concerning older people and population ageing is not a historical phenomenon, to this day highly respected reporters pronounce with certainty that population ageing is having stark and overwhelmingly negative consequences for society. Take this example:

It turns out it’s not the really old we have to worry about, it’s the nearly old, the ones who want to live hard and die not very young at all. With the poor twenty-first century tax payer footing the bill …

We’ve got a battle on our hands alright and judging from the past few weeks this isn’t going to end well for the young.

The quote above comes from Stephanie Flanders, who was then the Economic Editor of the high profile BBC current affairs programme Newsnight, and was used in a package on grey power that was broadcast in February 2005. Within this quote, and certainly within the full report from which it is taken, is a fast crystallising agenda on how to respond politically to the ageing of the UK population. Within this agenda is an apparent parallel fear and awe over the perceived onset of grey power. This framing of the implications of population ageing overlaps with many key components of neo-liberalism – the re-emergence of support for nineteenth century ‘classical’ liberalism applied to modern economics through advocating the reduction of the role of the state in welfare alongside net reductions in social spending by the state (Harvey 2005). According to the left wing theorist Robin Blackburn for neo-liberals the urge to use population ageing for ‘demographic doom-mongering’ in order to agitate for their preferred response of cutting back on public pensions and encouraging citizens to make provision for their own retirement by contributing to commercial pension funds, is irresistible (Blackburn 2002).

The view that the media, in particular, is encouraging and increasing anxiety about the implications of population ageing was endorsed by Andrew Smith, when he was a government minister. In a speech to an Age Concern conference (DWP 2004) the then Work and Pensions Secretary argued: ‘Too often in politics and the media, images of older people are negative. They’re accompanied by doom and gloom warnings about a potential health care or pensions crisis.’

In chapters 10–12 of this book, the period between 2005 and 2010 in British politics is used to examine in depth the mediation of the politics of population ageing. During this period a disconcerting case study arose that demonstrated the continuing acceptability of ageist content in the mainstream British media – the use of age to attack the then Liberal Democrat leader Ming Campbell. Campbell resigned as party leader in October 2007 bemoaning constant media references to his age, 66. Campbell suffered from ageist lampooning of his personal qualities, not least from The Guardian’s main political cartoonist Steve Bell. In cartoons published in 2006 Bell drew upon symbols of decrepitude and mental and physical decline to portray Campbell; zimmer-frames; wheelchairs; blankets over the legs; texts mimicking political slogans ‘prepare for death’ – and above the apparently comedic notion that a man in his mid 60s could hold a position of leadership. The treatment of Campbell is a stark example of how age prejudice still resonates with the writings on the subject by Simone de Beauvoir who argued that in western society age eventually turns everyone into a social problem (de Beauvoir 1970). de Beauvoir noted that it is rare for old age to be looked upon as the ‘crown of life’ and that society views time as belonging to the young to seek fulfilment, with older people forced to see themselves as ‘unproductive and powerless’.

Old age may have held a low social value for much of the twentieth century, but none the less, we might expect the current age-related demographic transformation of society might attract a considerable volume of attention from academia – not least from those with an interest in the political implications and the media’s portrayal of socially excluded groups. However, this has not been the case and the motivation to begin to fill this research gap has been compelling. Time and again o...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Great Age Transformation

- 3 Theories of Ageing

- 4 Age is a Political Issue: The Attempts to Frame Ageing as Socially Divisive

- 5 Ageist Stereotyping and Discrimination

- 6 Ageing in the Media

- 7 The Politics of Ageing: Age and Voting Behaviour

- 8 My Generation … My Life Story: The Role of Cohorts and the Life Cycle

- 9 Political Marketing and the Segmentation of the Grey Vote

- 10 Quantifying the Rise of the Grey Vote

- 11 Time Bombs and Greedy Boomers … Case Study Analysis: Elite BBC Reporting on the Political Implications of Ageing – Making a Drama out of a ‘Crisis’?

- 12 Mediating the Grey Vote: The UK General Election Campaigns of 2005 and 2010

- 13 Constructing the Grey Vote

- References

- Index