- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Raw: Architectural Engagements with Nature

About this book

Through cross-disciplinary explorations of and engagements with nature as a forming part of architecture, this volume sheds light on the concepts of both nature and architecture. Nature is examined in a raw intermediary state, where it is noticeable as nature, despite, but at the same time through, man's effort at creating form. This is done by approaching nature from the perspective of architecture, understood, not only as concrete buildings, but as a fundamental human way both of being in, and relating to, the world. Man finds and forms places where life may take place. Consequently, architecture may be understood as ranging from the simple mark on the ground and primitive enclosure, to the contemporary megalopolis. Nature inheres in many aesthetic forms of expression. In architecture, however, nature emerges with a particular power and clarity, which makes architecture a raw kind of art. Even though other forms of art, as well as aesthetic phenomena outside the arts, are addressed, the analogy to architecture will be evident and important. Thus, by using the concept of 'raw' as a focal point, this book provides new approaches to architecture in a broad sense, as well as other aesthetic and artistic practices, and will be of interest to readers from different fields of the arts and humanities, spanning from philosophy and theology to history of art, architecture and music.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Raw: Architectural Engagements with Nature by Solveig Bøe,Hege Charlotte Faber in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Sand. Water. Wind.

SAND

Berlin is built on sand that consists primarily of silicon dioxide.

The exhibition ‘Mythos Berlin’ was staged in West Berlin in 1987 as part of the celebrations of the city’s 750th anniversary. It was dedicated to the perceptual history of the vanished industrial metropolis, and the wasteland that once held the railway station Anhalter Bahnhof, the biggest railway station in Berlin, was chosen as the exhibition venue. The cover of the exhibition catalogue1 was made of sandpaper. An excellent choice in my view, as it reflects not only what is widely perceived to be the ‘rough’ character of Berlin, but also its distinctive substance, the Brandenburg sand. On my walks through the city I see this sand everywhere – anywhere that the ground beneath my feet is exposed.

1.1 Werner Heldt (1904–1954), Berlin am Meer, 1947, 36 × 46 cm. Private Collection. Jan Brockmann / © BONO.

The painter Werner Heldt (1904–1954), a native Berliner, was obsessed with this sand. It runs as a motif throughout his entire oeuvre.

One example of his obsession with the sand in Berlin is a black and white India ink drawing: Berlin on the Ocean2 depicts the back of a row of tenement buildings, their naked firewalls facing towards something reminiscent of – what, precisely? Is it the Baltic Sea, which has traditionally served as the Berliners’ ‘bathtub’, that is seen pouring into the city? Or did Heldt draw the sandy bed of a dried-out river, or perhaps a glacial deposit? If it is indeed sand that is depicted, it has a fluid character to it, as if it is flooding in, making waves that lick the sides of the buildings. This part of the image can also be viewed as a channel that the water has pulled out of, or is threatening to flood into. Along the left and right hand edges, Heldt’s brush has left marks that may signify a type of shrubbery commonly found in the shore zone along the North and Baltic Seas. The backyards are deserted, empty, and the windows are merely blind, black lines. The firewalls are still sooty from the infernal fires created by the phosphorous bombs, thus visualising the dual meaning of the word ‘firewall’: the very walls designed to serve as protection against fire have been blackened precisely by fire. A ruin forms a v-shaped section, like a funnel, in the left-hand corner of the image. It opens up towards a view of the ocean, where a steamship sailing across the high-lying horizon draws the viewer’s attention. The toy-like outline of the ship and its smoke trail creates an odd contrast to the sombre overall mood of the image. The tenement buildings, four storeys tall, form a comb-shaped structure. They have no adorning details, in contrast to the intact façade glimpsed in the background (towards the upper right-hand corner). This blandness was a typical feature of the Berlin backyards of the past, their endless, indistinct rows covering large areas in the working-class neighbourhoods. Even today, this can be observed to some extent, especially in the eastern parts of the city. After World War II Werner Heldt produced a series of images that are variations on this theme. His style became increasingly simplified. This was above all the case in his black and white works on paper, where the simplification was taken to such an extent that it approached calligraphy. And the topic the artist kept returning to, over and over, was the ravaged urban landscape of the post-war era.

But why does Heldt place Berlin by the sea? As the crow flies, the closest saltwater body, the Baltic Sea, is located some 200 kilometres north of the city. The North Sea lies even further away. Scharmützelsee, known as the ‘Märkischer See’ – the Brandenburg Sea – lies southeast of Berlin. It is the largest lake in the federal state of Brandenburg (part of the former Mark Brandenburg), which is home to some of Germany’s greatest water reserves. Nonetheless, Schwarmützelsee covers an area of scarcely 14 km2.

A more obvious explanation is that the references to the sea appearing in Heldt’s works are metaphorical, comparable for instance to poet Georg Heym’s (1887–1912) description of the city as the ‘Riesensteinmeer’, ‘the gigantic sea of rocks’,3 or to the metaphor ‘sea of people’.

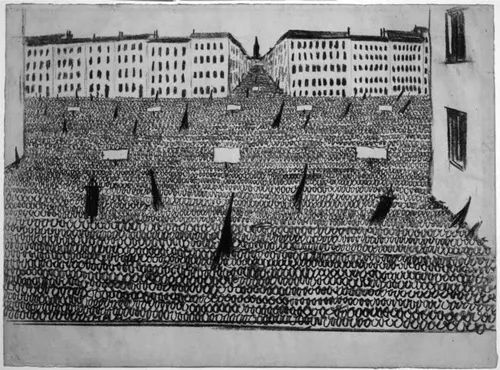

Already in 1928, Werner Heldt made a small pencil drawing depicting a densely packed crowd gathered under waving flags, filling the urban space like a stream. He entitled it Demonstration.4 And seven years later – alarmed in his Mallorca refuge by the rallying of the Nazis – Heldt picked up the same theme in a series of charcoal drawings where the masses appear as endless rows of zeroes threatening to force their way into the artist’s studio. These zeroes haunting the artist indicate his vulnerability not only to crowds, but also to emptiness. Werner Heldt had good reasons to fear the masses. He regarded himself as an outsider: he was a homosexual, and a modern, French-inspired visual artist. He was also given to melancholy, and suffered from heavy depressions from an early age. ‘Husum moods’ was Heldt’s name for his dark hours – a strange term which has many of the same sounds as the term ‘hüzün’, used much later by the author Orhan Pamuk to describe a similar atmosphere rife among the population of Istanbul. Heldt’s term alludes to the North German author Theodor Storm: in a melancholy tribute to a grey town and a grey sea, Storm remembers his birthplace Husum on the North Sea in the 1851 poem Die Stadt.5 In keeping with the mood in Storm’s poem, Werner Heldt describes Berlin in his own poem Meine Heimat (My home town) from 1932:

1.2 Werner Heldt, Meeting (Parade of the Zeros), coal on laid paper, 1935, 46.8 × 63 cm. Courtesy, Berlinische Galerie, Berlin / © BONO.

I was born in a big grey city where the rain falls forever on a sea of roofs, and the boundaries are lost on the horizon. The grey city is my home, my World … where a hundred thousand pale buildings are huddled together, pondering a dream of the distant sea behind their dead eyes …6

The words evoke a lifeless city in all of its bleakness, long before the devastation brought by the bombs. In contrast, Heldt’s drawing shows a cheerful steamboat sailing across the sea: the very vision of a world secure from harm. Thus, the boat offers a childlike imaginary escape from the universal misery (Plate 1). Many Berliners shared the artist’s dream. As early as the 1920s, the city’s great Jewish satirist Kurt Tucholsky described the Berliner’s ideal dwelling as a house on the Baltic Sea – whose back door opened onto Berlin’s Friedrichstraße.7

In the wake of WWII, the artist drew the devastated city of Berlin over and over, tall piles of rubble and sand towering among the ruined buildings. However, he had found this topic much earlier. He photographed heaps of sand left behind from the demolition of buildings in the city’s poor districts as early as 1930. At the same time, Berlin on the sea first appears as a topic in his art. Ten years later he painted a picture (destroyed during the war) reminiscent of Utrillo’s paintings from Montmartre: a lone male figure is depicted in a rowing boat in a deserted village-like scene not unlike many of Berlin’s suburbs. In Heldt’s new version of this painting from 1951 the man is depicted as an angler, but the deserted, dreamlike character of the scene is retained. A likely interpretation of these images is that their theme is death. The river running through Berlin, Die Spree, has become the river of the Underworld, Acheron, and the lone rower represents Charon.

In Werner Heldt’s art, the idyllic meets disaster. The environment is reclaimed by the once-displaced natural world. The city that used to contain masses of people – plentiful like the grains of sand by the sea – is now completely deserted. Thus sand, just as much as water, serves as the artist’s metaphor for the ‘sea’. We might say that sand represents the ‘ashes’ of the sea. A painting from 1946 with the same leitmotif (‘Berlin on the sea’) shows an empty vessel without sails ploughing her way through the deep sand of the city.8 Thus, the slowness of time is indicated by this image in much the same way that the passage of time is represented by the grains of sand falling inside an hourglass.

Werner Heldt lived in the Western part of the city. But many artists in the East were also contaminated by Berlin’s inevitable gloom and melancholy during the 1950s – despite the officially prescribed optimism.

A photograph I took in 2002 at Checkpoint Charlie shows rubble and sand dunes which look identical to the rubble and sand dunes in Werner Heldt’s photographs from the 1930s. (Checkpoint Charlie is where US and Soviet tanks confronted each other on 27 October 1961, when the wall was erected; it is also world renowned as the entry point to East Berlin for non-German visitors from the West, up until the fall of the Wall.) The situation remains the same in many places even today, for ‘underneath the asphalt lies the land of Mark Brandenburg. And this sand was once the floor of the sea … nature reclaims that which man has constructed in his hubris’.9

Werner Heldt is not alone in associating Berlin with sea and sand. Around 1919 the poet Oskar Loerke (1884–1941) – best known for the symbolism of his nature poetry – wrote the sonnet Blauer Abend in Berlin [Blue Evening in Berlin], where he evokes an image of a city situated on the sea floor. In the two final lines he likens people to sand: ‘Die Menschen sind wie ein grober Sand/Im linden Spiel der großen Wellenhand’ – ‘People are like a coarse kind of sand/in the gentle play of the waves’ big hand’.10 Like in Werner Heldt’s drawings, the idea of ‘masses of people, plentiful like the sand by the sea’ is the metaphorical starting point. Shortly after the end of the war the writer Karl Korn notes that wandering through the ruins of the city gives him a feeling of being surrounded by masses of boulders, as if on the bottom of the sea.11 And as late as 1961 the novelist Wolfdietrich Schnurre writes, in connection with the erection of the Wall: ‘God Almighty, we are not walking along the bottom of the sea; we are walking across Berlin’.12 The sea sand is everywhere. It is all-pervasive.

1.3 At the Checkpoint Charlie, 2002. Courtesy of Jan Brockmann.

For centuries, Mark Brandenburg was ironically called ‘Streusandbüchse des Heiligen Römischen Reiches deutscher Nation’ [‘sandbox of the holy Roman realm of German nation’]. Travellers bound for Berlin could not help but notice that the nickname was appropriate. Often, the deep sand would bring their horse taxis to a halt. ‘Berlin lies next to a sandy desert’, writes Stendhal in 1806, ‘how anyone thought of founding a settlement in this sand is beyond me’.13 The great painter of Brandenburg and Berlin, Carl Blechen (1798–1840) – professor of landscape painting in Berlin during the first half of the 1800s – painted several pictures of this distinctive landscape and its sand, heath, and pine trees. Among this body of work is a small study showing three women shuffling sand into a basket – the very image of meaningless toil, one might think (Plate 2). However, making a living was a difficult task, and sand came in different qualities. Good quality sand was needed as building material and in the production of pottery; and the housewives of Berlin tended to use the fine sand in the scrubbing and sweeping of their floors.

1.4 Beach bar at the Bundespresseamt, 2006. Courtesy of Jan Brockmann.

Today the sand is shipped on barges on the Spree River to different sites along the banks to be spread out on one of the 15-plus beach bars where the strollers can take a well-deserved rest, stretch out on the deckchairs in the sun if they are lucky, or sip Mediterranean cocktails under the parasols. The sand is also used for beach volleyball arenas in the city centre. And since 2003 the sand is indispensable during the annual ‘Sandsation’: international competitions for sand sculptors arranged as part of the ‘United Sand Festivals’ (USF).

The streets and pavements of Berlin rest in this sand. The pavements’ ‘Schweinebäuche’, ‘pigs’ bellies’, have turned out to be among Berlin’s most durable manmade features. The ‘pigs’ bellies’ are large, heavy slabs of Silesian granite whose undersides are rounded to prevent them from sliding on the sand. They were first used in the early nineteenth century and have proved very resilient, even against the shelling and bombing of the war. The initial paving work requires great precision. In the 2010 exhibition InnenStadtAußen [InnerCityOutside], the Icelandic-Danish artist Olafur Eliasson (professor at Universität der Kün...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- About the Editors

- About the Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Sand. Water. Wind.

- 2 Ruskin, Rocks and Water

- 3 Building and Belonging: John Ruskin on the Art and Nature of Architecture

- 4 A Visual Journey into Environmental Aesthetics

- 5 The Illumination of Time in Space: Experience of Nature in Vejleå Church

- 6 Nature in Sacred Buildings

- 7 The Making of Atmosphere in Architecture

- 8 Natural Wine and Aesthetics

- 9 Nature per Fumum: Perfumes, Environments and Materiality

- 10 Impressions of Nature in Rautavaara’s Music

- 11 The Raw, the Hidden and the Sublime: Four Artworks and One Bridge

- 12 The Raw Within: Tracing the Raw in Human Life Through Bricks, Roy Andersson’s You, The Living and Ernst Barlach’s Beggar on Crutches

- 13 ‘Lifelining’ Landscapes: Aesthetic Encounters with Nature

- 14 Aesthetic Values and Ecological Facts: A Conflict, a Compromise, or What?

- 15 RAW Contained

- Index