- 338 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Green Parties in Europe

About this book

The emergence of green parties throughout Europe during the 1980s marked the arrival of a new form of political movement, challenging established models of party politics and putting new issues on the political agenda. Since their emergence, green parties in Europe have faced different destinies; in countries such as Germany, Belgium, Finland, France, and Italy, they have accumulated electoral successes, participated in governments, implemented policies and established themselves as part of the party system. In other countries, their political relevance remains very limited. After more than 30 years on the political scene, green parties have proven to be more than just a temporary phenomenon. They have lost their newness, faced success and failure, power and opposition, grassroots enthusiasm and internal conflicts. Green Parties in Europe includes individual case studies and a comparative perspective to bring together international specialists engaged in the study of green parties. It renews and expands our knowledge about the green party family in Europe.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Green Parties in Europe by Emilie van Haute in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Case studies

1

The Greens in Austria and Switzerland

Two successful opposition parties

Introduction

The Austrian and Swiss Greens belong to the successful members of the Green party family. Since 1979 and 1986 (Switzerland and Austria, respectively), they have been represented in the national parliament. Their vote shares are close to (Switzerland) or even above (Austria) 10 per cent, and they are also represented in several governments at the regional and local levels. However, government participation at the national level has been so far out of reach.

This chapter covers the two parties’ electoral, programmatic and organisational developments. As regards the contextual factors that influence these developments, Austria and Switzerland are federal countries whose political elites often follow inclusive strategies towards challengers. Especially in the beginning of their development, the Greens benefited from open political opportunity structures. The central role of direct democracy is a unique feature of Swiss politics, but both countries share other relevant characteristics: Populist radical right parties are extremely strong (McGann and Kitschelt, 2005), and immigration and European integration are major issues for which the Greens and the Populist radical right present genuinely different answers (Kriesi, et al., 2008, 2012).

The main focus of this chapter will be on the two parties that have dominated the Green political spectrum since the late 1980s at the national level: Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Greens) in Austria and the Grüne – Grüne Partei der Schweiz (GPS) in Switzerland. Until the 1990s, both had to deal with competing Green parties before they achieved a dominant position. While the Austrians have not experienced any Green challenger since then, their Swiss sister party has been confronted with a relevant splinter party since the mid-2000s, the Grünliberale Partei Schweiz (GLP).1

The chapter proceeds as follows: it first briefly summarises the origins and development of Green parties in both countries. Subsequently, it deals with the Greens’ ideology and policy positions, as well as their organisation. Finally, the chapter discusses some of the main challenges that both parties face in the near and mid-term future.

Origins and development

In Austria, the early development of the Greens until the mid-1980s was characterised by two major and finally successful instances of public protest. In 1978, opposition against the use of nuclear energy led to the world’s first national referendum on this topic. A thin majority (50.5 per cent) voted against bringing into service an already completed power plant in Zwentendorf, near Vienna. While at that time opposition to nuclear energy was also tactically directed against the government led by the Social Democrats (SPÖ), it later turned into a kind of ‘state doctrine’. A few years later, in the winter of 1984–1985, protests stopped the construction of a hydroelectric power station on the Danube near Hainburg, close to the then Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (now Slovakia). First, the government declared a ‘Christmas peace’ and postponed further forest clearances; later, the area became a national park. In the electoral arena, by contrast, the first Green breakthrough happened in the west of the country. Already in 1977, the Bürgerliste Salzburg won two seats in the local council.

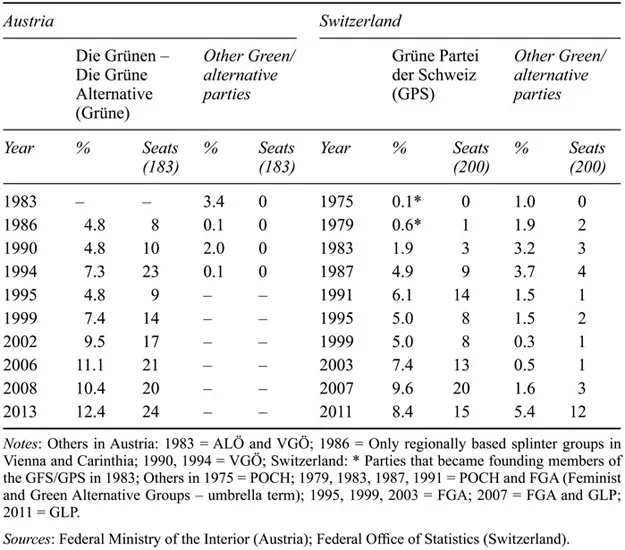

In 1982, veterans of the antinuclear movement founded first Green party at the national level: the Vereinte Grüne Österreichs (VGÖ). These ‘pure Green’ reform-ists were a rare example of a conservative Green party (Poguntke, 1989). A second party was founded the same year, the Alternative Liste Österreichs (ALÖ). Contrary to the VGÖ, this party represented the left-wing and radical part of the Green movement. However, the relative weakness of new social movements in Austria severely limited its impact (Dolezal and Hutter, 2007). Because of programmatic and personal differences, the two parties competed separately in the 1983 national election (Table 1.1). This division prevented them from gaining parliamentary representation: had they competed together, they could have won at least five seats (Haerpfer, 1989).

The protests against the Danube power station and the first successes in regional elections in which the Greens had combined their forces2 led to new efforts to build a common Green candidacy at the national level. In 1985, prominent Green activists formed a loose organisation called Bürgerinitiative Parlament (BIP). In spring 1986, they nominated Freda Meissner-Blau as candidate for the presidential election. In the first round of this poll, the 59-year old ‘Grande Dame’ of Austria’s environmental movement won 5.5 per cent of the votes. In the early parliamentary election held in November, Meissner-Blau led a united Green list (Die Grüne Alternative – Liste Freda Meissner-Blau), which was backed by a majority of both the ALÖ and VGÖ. The Greens won 4.8 per cent and secured 8 out of 183 seats in the Nationalrat (Table 1.1). Since then, they have continuously been represented in parliament. Since 2001, they have also been present in the – largely irrelevant – second chamber (Bundesrat).

Shortly after the 1986 election, a new party was founded: the Grüne Alternative (GA). It successfully absorbed the ALÖ (Haerpfer, 1989). However, the heterogeneity of the Green movement immediately led to struggles in the parliamentary party and to a rival candidacy by the VGÖ in 1990, which again split the Green vote. Subsequently, the VGÖ moved ever more to the right and became insignificant. Apart from the conflict with the VGÖ, the first half of the 1990s was characterised by important organisational adaptations that turned the Greens into a ‘normal’ and more professional party and gave it its current name (see below).

Table 1.1 Election results in Austria and Switzerland – federal (% votes and N seats)

The national elections held in 1994 and 1995 already demonstrated a higher professionalisation as the Greens had for the first time a real top candidate: Madeleine Petrovic. In 1990, they had been led by a team of four. After success in 1994 (7.3 per cent), the Greens lost in 1995 (4.8 per cent) because this sudden election was dominated by a strong polarisation between the major parties, the Social Democrats (SPÖ) and the Conservatives (ÖVP). Additionally, the Liberal Forum, a left-libertarian scission from the Populist radical right (FPÖ), proved to be attractive for many potential Green voters (Table 1.1). Petrovic resigned but remained head of the parliamentary party. In a close vote at the subsequent party congress, Christoph Chorherr was elected the new party leader. But he resigned after less than two years due to internal conflicts on the Greens’ programmatic orientation (Williams, 2000).

Since the late 1990s, the Greens managed to stabilise under a new party leader, Alexander Van der Bellen. They increased their vote shares in almost every election. In the three most recent polls, they won above 10 per cent (Table 1.1).

While their results have been above the average of European Green parties, government participation at the national level has remained out of reach. In 2002, they held initial talks with the ÖVP, which immediately provoked strong internal opposition from the party’s left wing (Lauber, 2003). Nevertheless, in recent elections, the Greens did not rule out a coalition with either the SPÖ or the ÖVP. Given the secular decline of both traditional parties, the Greens’ plan for the 2013 election was to join a three-party coalition. But the ‘old’ parties secured a short majority and finally built another grand coalition, which consigned the Greens again to the opposition benches (Dolezal and Zeglovits, 2014).

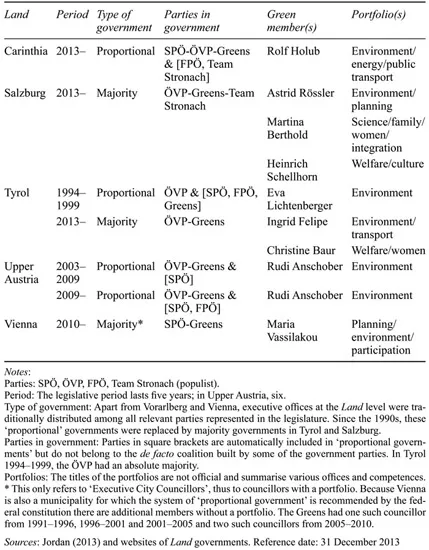

Contrary to the national level, the Greens had already participated in several governments at the Land level (Table 1.2). They entered a Land government for the first time in Tyrol (1994–1999), which then still used a system of ‘proportional government’ that distributed executive offices among all parties with a certain share of seats in the legislature. Since 2003, the Greens have governed with the ÖVP in Upper Austria (within another ‘proportional government’); since 2010, they have been in power with the SPÖ in the city-state of Vienna. After highly successful elections in the first half of 2013, the Greens joined three additional coalitions and were thus represented in five out of nine regional governments (Dolezal, 2014).

Compared to the Austrians, the Swiss Greens do not share a major common or even ‘mythical’ event such as the above-mentioned referendum on Zwentendorf or the protests in Hainburg (see Table 1.4 at the end of this section). Nevertheless, new social movements were comparatively strong in the 1970s and 1980s, and they had similar close linkages with the Greens (Kriesi, et al., 1995). Overall, the Swiss Greens’ history is even more complex than the Austrians’ and is heavily influenced by some unique features of Switzerland’s political system.

The Greens’ development began in the French-speaking part of the country (Seitz, 2008). In 1971, opponents of a planned motorway on the lakefront of Neuchâtel founded the Mouvement populaire pour l’environnement and entered the city’s assembly in the following year. In 1978, the Groupement pour la protection de l’environnement achieved representation in the cantonal legislature of Vaud where one year later Daniel Brélaz was elected into the Nationalrat (Ladner, 1989). He was the first Green representative in a national parliament worldwide.3 Since then, ‘moderate’ Greens have been represented in parliament; since 2007 also in its equally important second chamber (Ständerat) (Table 1.1).

In 1983, thus one year after Austria, two parties were founded at the national level: the moderate Föderation der grünen Parteien der Schweiz (GFS) and the more radical Grüne Alternative Schweiz (GRAS). In addition, the radical left Progressive Organisationen der Schweiz (POCH) mobilised on ecological matters (Ladner, 1989). This split of the Green movement resembled the situation in Austria, but because of a lower threshold of representation,4 the GFS nevertheless secured three seats in the 1983 national elections by winning just 1.9 per cent of the votes. In 1987, both parties ran again separately. The moderate Greens had renamed themselves into the Grüne Partei der Schweiz (GPS); the radicals operated as Grünes Bündnis Schweiz (GBS). Both parties managed to (re)enter parliament.

In the 1990s, the GPS became the dominant Green party in Switzerland. All cantonal organisations of the alternative Greens were integrated step by step into the federal party in a long process that had already started with the Demokratische Alternative Bern in 1985 (Seitz, 2008) and that finally ended with the canton of Zug in 2009 (Grüne/Les Verts, 2013b). In the beginning of 2014, the GPS was present in 24 out of 26 cantons.5 The incorporation of the alternative branches changed the Greens’ profile and moved the party towards the left. In the 1980s, by contrast, the GPS was dominated by moderate ‘conservationists’ and thus rather resembled the Austrian VGÖ (Poguntke, 1989).

Table 1.2 Government experience at the Land level in Austria

Although parliamentary representation at the national level was secured, no real electoral breakthrough occurred in the 1990s. Additionally, government participation was – and still is – out of reach. In 1993, a party conference declared a basic commitment to join the Bundesrat, the federal executive. In advance of...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Notes on contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I Case studies

- Part II Comparative perspective on Green parties in Europe

- Index