- 210 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Masculinity and Queer Desire in Spanish Enlightenment Literature

About this book

In Masculinity and Queer Desire in Spanish Enlightenment Literature, Mehl Allan Penrose examines three distinct male figures, each of which was represented as the Other in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Spanish literature. The most common configuration of non-normative men was the petimetre, an effeminate, Francophile male who figured a failed masculinity, a dubious sexuality, and an invasive French cultural presence. Also inscribed within cultural discourse were the bujarrón or 'sodomite,' who participates in sexual relations with men, and the Arcadian shepherd, who expresses his desire for other males and who takes on agency as the voice of homoerotica. Analyzing journalistic essays, poetry, and drama, Penrose shows that Spanish authors employed queer images of men to engage debates about how males should appear, speak, and behave and whom they should love in order to be considered 'real' Spaniards. Penrose interrogates works by a wide range of writers, including Luis Cañuelo, Ramón de la Cruz, and Félix María de Samaniego, arguing that the tropes created by these authors solidified the gender and sexual binary and defined and described what a 'queer' man was in the Spanish collective imaginary. Masculinity and Queer Desire engages with current cultural, historical, and theoretical scholarship to propose the notion that the idea of queerness in gender and sexuality based on identifiable criteria started in Spain long before the medical concept of the 'homosexual' was created around 1870.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Masculinity and Queer Desire in Spanish Enlightenment Literature by Mehl Allan Penrose in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Critique littéraire. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

LittératureSubtopic

Critique littérairePART I

The Reinvention of Masculinity and the Problematic Petimetre

Chapter 1

The Invocations of Hermaphrodism in the Periodicals El Censor, El Duende Especulativo, and El Pensador

In 1792, a 27-year-old Capuchin nun named Fernanda Fernández began noticing a bodily transformation in which her sexual organs changed from female to male. After two years, the transformation was complete and she declared herself a male. The doctors who examined her agreed, after initially diagnosing her with insanity because she could not resist the carnal temptations induced by the sight and proximity of her fellow nuns. Fernanda was renamed Fernando and was allowed to wear male clothing, but s/he was stripped of her ecclesiastical vows and was made to leave her convent. S/he continued to utilize the skills considered “womanly” that she learned in the convent1.

Fernanda’s case is made all the more interesting because it occurred at a time when the vast majority of Enlightenment doctors, scientists, naturalists, and philosophers no longer believed that such sex transformations could take place. They were considered by the intelligentsia to be part of the superstitious and ignorant beliefs held by the masses. Fernanda’s fascinating transition to Fernando occurred at a time when Spain was enthralled by and, at the same time, afraid of the idea of hermaphroditism, cross-dressing, castrati, and masquerades in which gender roles and appearances were reversed. There was, in short, an obsession with gender and sexual transgressions that was part of a wider debate about gender limitations and sexual ambiguity (Vázquez and Moreno, Sexo y razón 200). This debate played out mostly in the press, which added to it other polemics equally as controversial, such as the power of the supposedly decadent foreign (especially French) influences on Spaniards and the cultural purity or casticismo of Spanish subjects. Spanish writers and moralists, like scientists and doctors, were very preoccupied about the stability of masculine gender, and they played on popular anecdotes like the one about Fernanda/Fernando to underscore the encroaching powers of women. Fernanda, in her transition from woman to man, embodied the intellectual polemic in the second half of the eighteenth century about the anatomical, mental, and spiritual nature of men and women: was gender an inherent characteristic of a person, or was it formed by social convention?2 If sex was a God-given anatomical attribute, how could a transmutation such as Fernanda’s happen and what effect did it have on the brain and soul?3

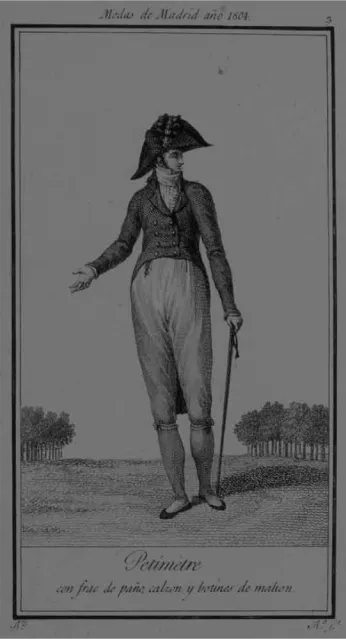

As part of that debate, numerous late eighteenth-century satirists and moralists planted the notion of a hermaphroditic, foreign creature in their works who challenged accepted notions about masculinity and femininity.4 These writers presented a new version of an eighteenth-century figurón or stock figure, the petimetre,5 in cultural products that ranged from theatrical skits to poems to songs. This figure was clearly ambiguous in terms of his gender, as Martín Gaite, González Troyano, Haidt (“Fashion, Effeminacy,” Embodying Enlightenment), Prot, and I (“Petimetres,” “The Imaginary Hermaphrodite”) have shown, and he was associated ironically with women, hermaphrodites, animals, and monsters. In all but the first sense the writers were carefully constructing the idea of a man who was not really a human at all.6 The “birth” of this character in eighteenth-century satirical discourse served to exclude the real men he was supposed to represent—the effeminate, weak, whimsical, unstable, and afrancesado7—from the heteronormative dichotomous gender economy. By creating the name petimetre to connote an Other, an “it,” satirists reiterated the boundaries of the human, rendering petimetres inhuman in a process Butler terms “interpellation.”8 Even the descriptions of these characters as would-be women make them virtually inhuman, for women too at the time were considered deformed and imperfect.9 The motive behind the induction of this caricature in national discourse was to warn Spanish men, especially those of the privileged classes, not to succumb to the temptations of excess, frivolity, and luxury that were associated with women and which petimetres embodied, and to resist both the supposedly debilitating effects of the feminine and of the foreign, specifically, the French. Satirists employed irony to manipulate age-old beliefs that held that people’s anatomical sex could change and, subsequently, their corresponding gender. These authors created caricatures of afeminados (effeminate men)10 as androgynes11 principally to underscore the gender instability they performed in their quest for luxury, social superiority, and attention as objects of desire. Men’s effeminacy purportedly created this instability in their gender and, these writers ironically suggested, in their sexual constitution.

Fig. 1.1 “Petimetre.” Source: Antonio Rodríguez and Manuel Alegre (1804). Museo de Historia de Madrid. Inv. 2343.

Although modern readers, including many of my college students, tend to think of petimetres, who minced about as fashionistas with made-up faces and perfumed bodies, as “homosexual”—an anachronistic label to be sure since the word refers to a social and medical construct associated with being as well as doing that did not originate until the late nineteenth century—they were rarely explicitly labeled as non-normative in their sexual behavior, although there are texts that make the connection clearly. I argue below that these texts put into question Haidt’s perspective on this issue that there was no overt association between effeminacy and sodomitical practices: “… Spanish commentators did not explicitly link petimetres and sodomy…” (emphasis original; “Fashion, Effeminacy” 71).

Indeed, their sexuality was not primarily the point of the satirists, unlike the medical discussions about the hermaphrodite. It was precisely the petimetre’s inability to perform normative roles that rendered him queer in his gender and sexuality. The guiding conviction of this chapter is that by displacing a feminine gender and dubious sex and sexuality onto the trope of the hermaphroditic, effeminate male, Enlightenment periodical writers in general revealed through their ironic caricatures a fundamental paradox about whether a person’s gender and sex were mandated by nature or if s/he learned particular behaviors through social customs and attitudes. Even though the goal of moralists and satirists was to correct what they considered inappropriate behavior by ridiculing effeminate men, in effect they reinforced the confusion about the nature versus nurture debate. The serious message behind the irony was intellectuals’ concern for the loss of traditional Spanish values, which favored men in the social hierarchy. As the eighteenth-century Spanish intelligentsia solidified its belief that there were two biological sexes—in other words, no true hermaphrodites—corresponding to two distinct genders, the androgyne became a ubiquitous satirical figure to bolster the extant gender-sex economy through the exploitation of a negative example and to combat literature of the marvelous, superstition, and the masses’ lack of knowledge about nature, which all allowed for the existence of hermaphrodites and “miraculous” sex changes (Vázquez and Cleminson 8). The petimetre also functioned as the illegitimate opposite of a normalized burgher, who was invested in the sanctity of marriage and procreation. Both represented a primary concern of liberal thinkers and administrators of Old Regime monarchies, who argued that the modern nation should have an abundant and healthy population as one of many resources for the nation (Vázquez and Cleminson 24).

I take as my starting point for this discussion not only Butler’s theory about the gendered relations matrix discussed in both Gender Trouble and Bodies That Matter but also the questions that intellectuals began to pose starting in the Modern era about the sexual nature of hermaphrodites, including whether they were a mixture, an absence, or a dubious state in relation to sex.12 I argue that Enlightenment satirists and moralists utilized this medico-legal polemic to construct the trope of the afeminado as a mixture of masculine and feminine genders (though carefully avoiding the mention of biological sex) and to suggest a hermaphroditic queerness in his sexuality, not necessarily because he engaged in sexual relations with men, but because he lacked the normative gender characteristics and sexual drive that would have enabled him to marry and have children.

In this chapter, I will offer a reading grounded in queer studies on the androgynous male figures presented in several essays of Luis Cañuelo, José Clavijo y Fajardo, and Juan Antonio Mercadal, three of some of the most prominent journalists at the end of the eighteenth century, as representative examples in which the afeminado or androgyne is imbued with hermaphroditic attributes. The journalistic essay was to be, next to theater, the predominant genre in which the symbolic hermaphrodite was caricatured due to its possibilities as a costumbrista text.13 Before I get started with a discussion of gender-bending characters in these writers’ works, I will first explore the interpretations of androgyny and hermaphroditism in eighteenth-century Spain and the Spanish origins of the petimetre.

The Androgyne and Hermaphrodite

Commencing with cultural discourse of the Western classical period, the idea of the androgyne was conflated with the notion of the hermaphrodite, which is now referred to as intersex and is the state of having ambiguous genitalia or both male and female sets of genital organs. Marie Delcourt traces the conception of the androgyne back to classical Antiquity, when s/he took the monstrous and mystical form of the Phoenix (79–80). The androgyne represents one of the oldest manifestations of desire and appears in several cultures as part of their creation myths (Diego 23–5).14

Canonical and civil thought on this topic in Spain in the Middle Ages and the early modern period was influenced heavily by classical antiquity, principally by Ovid’s version in Metamorphoses of the story of the Greek mythological figure, Hermaphrodite, who was overpowered by the nymph Salmacis while bathing and was joined bodily with her by the gods. The Spanish imaginary was also shaped by Plato’s The Symposium (385–80 BCE). In this philosophical text recounting several Athenian intellectuals’ speeches in praise of Eros, Aristophanes, one of the attendees, describes the nature of human anatomy and the creation of mankind, explaining that at one time, there was man, woman, and “androgynous,” although this latter dual-sexed human eventually disappeared (22). In fact, Aristophanes also confounds the notion of androgyny with hermaphroditism.15

It was the fascination and terror of a person with both sexes that ruled the imagination of civilizations, more so than the more abstract and spiritual notion of the androgyne. Indeed, the reality of the dual- or ambiguously-sexed body was never ascribed positive values in ancient Greek and Roman culture. Marie Delcourt has shown in her study of the classical world that the idea of divine intersex was more palatable than the corporal manifestations of it. Hermaphrodite was a s/he god and worshipped as such, while a baby born in classical Greece or Rome with ambiguous genitals was exposed to the elements or killed because s/he was considered a monstrous aberration of nature (45).

Medieval and early modern Western culture viewed hermaphrodites with both awe and, to some degree, uncertainty or even horror. However, jurisprudence did recognize their existence.16 Both civil and canonical law in the Spanish Middle Ages and the Renaissance was based on the belief that there were persons with features of the male and female versions of the sex on their bodies (i.e., both external and internal penises) (Vázquez and Moreno, Sexo y razón 187). Nonetheless, a single sex, either male or female, was imposed on the hermaphroditic person via the assignation of a name, normally at childbirth by the father or godfather. In that way, and through the hermaphrodite’s oath before marriage that s/he would continue with the sex given to him or her until the end of life, the hermaphrodite avoided being labeled a monster. The hermaphrodite was considered part of the “natural” order, if odd (Vázquez and Moreno, “Un solo sexo” 96–9). Laqueur posits that in early modern Europe “maleness and femaleness did not reside in anything particular. Thus for hermaphrodites the question was not ‘what sex they are really,’ but to which gender the architecture of their bodies most readily lent itself” (135, emphasis original).17

Perhaps it is for that reason that Elena/Eleno de Céspedes (1545?–1588) “fooled” the doctors summoned by the Inquisitorial court to establish whether she was a hermaphrodite or not into thinking that she indeed did possess both sets of reproductive organs. After being called before the court again because of doubts about her sex and subsequent to a close examination by ecclesiastical authorities of her private parts, they decided that Elena was a female. She was sentenced to two hundred lashes and ten years confinement to a hospital as a surgeon to the poor (Burshatin 420–51).18 Her case became famous and created a controversy in Spain that would last for many years.

So too did the story of Catalina de Erauso (born in 1592), the “nun ensign,” who went by Alonso Díaz and dressed and acted like a man until her death. Unlike Elena de Céspedes, she was granted a generous pension by Felipe IV and was not made to wear feminine attire.19 Both De Céspedes’s and Erauso’s cases generated publicity and added to the interest in the topic of cross dressers and sexually- and gender-ambiguous persons. Erauso so fascinated the Spanish imaginary that she inspired the play La monja alférez (The Nun Ensign), attributed to Juan Pérez de Montalbán (Donnell 27).

Men who transmuted to women were comparatively rare. As Velasco points out, in the early modern period post-natal male-to-female transmutations were thought to be very uncommon by the scientific community, since nature, it was believed, tended toward perfection, and men transmuting to women was seen as degeneration (Male Delivery 94–5). Bolufer and Jones/Stallybrass suggest that changes in sex during this period were only female-to-male in nature for the same reason (“Medicine” 88; “Fetishizing Gender” 84). Jones and Stallybrass cite followers of Galen and Aristotle, who appealed to the laws of nature rather than to medical observation. By the eighteenth century, “miraculous” sex changes were viewed very skeptically by the medico-scientific communities. However, in the literature of the “marvelous,” which enjoyed a popular public reception, “sex improvements” (transmutations of women into men) were still a common theme (Vázquez and Moreno, Sexo y razón 199).

It is no surprise, then, that Spanish writers since the medieval period have employed the image of the gender-ambiguous and hermaphroditic person to connote queerness in semblance, speech, and comportment.20 The idea of the dual-sexed person was most often represented in early modern literature by the androgyne—the effeminate male or the masculinized female—a stock character studied by several scholars.21

Hermaphroditism in Eighteenth-Century Spain: Anatomy as a Basis for the Other

The 1726 Diccionario de Autoridades (Dictionary of Authorities) defines hermaphrodita as an individual with both sets of sexual organs who is also called “androgynous.” The hermaphrodite is, the definition continues, a “monstrosity” whose origins were still controversial and whose meaning could be applied to “other things” (vol. 4, 144).22 As the Diccionario reveals, hermaphroditism was still employed interchangeably with androgyny in Spain. This was the norm up until the end of the century, when Joseph Plenck’s widely studied surgical manual Elementa Medicinae et Chirugiae Forensis was translated into Castilian. In it, Plenck describes three varieties of hermaphrodites: the “andrógino” or masculine hermaphrodite; the “andrógina” or feminine hermaphrodite; and the “true hermaphrodite” who exhibits both sex organs. The physician was “obliged” to categorize the hermaphrodite, whose genitalia was described as “monstrous,” in order for him/her to enter into marriage (116–17).

Eighteenth-century society conceived of the hermaphrodite as part of the teratological world, removed from the “natural” sphere, at least until the dawning of the Enlightenment, as evidenced by the Diccionar...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Inventing the Queer in Eighteenth- and Early Nineteenth-Century Spain

- Part I The Reinvention of Masculinity and the Problematic Petimetre

- Part II The Invention of Sexuality and the Homoerotic Male

- Conclusion: A Newly Emerging Consciousness

- Works Cited

- Index