![]()

1

A new man in politics

Vespasian’s career was a product of the social revolution that accompanied the change from Republic to Augustan Principate. Not only Marxist class but rank kept Roman society stable. Lines between Roman and non-Roman, slave and free, between plebs and the equestrian and senatorial orders, and between these orders, were reinforced under the principate. But deserving men could cross them and look forward to seeing sons and grandsons crossing others. Permeability strengthened the system.

A parvenu underwent severe scrutiny. His beginnings could be presented by detractors as degrading. A poverty-stricken boyhood, involving manual work on his parents’ farm and preventing him from acquiring an education, was ascribed to Gaius Marius, the great general from near Arpinum. Origin outside Rome (Arpinum had not received Roman citizenship until 188 BC) made a man liable to attacks that were hard to disprove when he had grown up in obscurity. Titus Flavius Vespasianus, born in the evening of 17 November AD 9 at a hamlet in the Sabine country, was, with his elder brother T. Sabinus, the first of those Flavii to rise to senatorial rank; both reached the consulship, Sabinus rose to the Prefecture of the City, and Vespasian rose unthinkably high for a man of his origins, whatever his gifts and industry.1

Suetonius did research. On his father’s side, Vespasian was descended from T. Flavius Petro of Reate, who had fought as centurion or evocatus for the Republicans at Pharsalus in 48 BC, escaping home from the battlefield. The sixty centurions of a legion could come from the stratum of society just below that of the knights, or rise slowly from the ranks. Evocati were men recalled after retirement, with prospects of promotion, and Petro may have been a veteran of Pompey’s Eastern campaigns (67–63 BC). He secured a pardon and honourable discharge from Caesar and, back in civilian life, took up the profession of debt collector.

Petro married a woman from Etruria, Tertulla, and his son, Vespasian’s father, is the first known T. Flavius Sabinus of the family, which is the earliest attested in which brothers had the same forename, and in successive generations. The ethnic surname may be taken from a forebear or be intended to distinguish this from another branch elsewhere. On Sabinus’ career, some said that he reached the post of leading centurion in a legion, as one might have expected from a man of his background; others said that he reached only an ordinary centurionate when he had to retire for health reasons. Suetonius, however, states roundly that he did no military service before undertaking collection of the 2.5 per cent due on goods entering or leaving the province of Asia, where statues were erected in tribute to his fairness. Sabinus went on to become what Suetonius describes as a money-lender or, more politely, banker (faenus exercuit) amongst the Helvetii, where he died. It was a shrewd enterprise, with the advance of Roman control to the Danube: their homeland between the Rhine, Jura, and the Lake of Geneva was developing, and there would be demand for capital from ambitious provincials keen to better themselves. But it was probably official functions that originally took Sabinus north: service in the company responsible for collecting the 2.5 per cent tax in Helvetian territory; as a centurion he might already have been involved in tax-collecting. There he died, survived by his wife and two sons; his eldest child, a girl, had not lived to her first birthday. The conventional view has Sabinus’ service in Gaul in the principates of Augustus and Tiberius, but a seductive hypothesis of D. Van Berchem puts his sojourn later: when Claudius opened up the Great St Bernard Pass in 46, the development of Helvetian territory gave scope for the banker’s activities; hence it may have been Vespasian himself who recommended Aventicum to his father, when he was already legionary legate at Argentorate – and after the expenses of his praetorship caused him financial difficulties. A nurse of ‘our Augustus’ is commemorated on a funerary monument of Aventicum, not Vespasian’s nurse, as is usually supposed, surviving until her charge was at least 60, but that of Titus, his son, who was left with his grandfather while Vespasian took part in the invasion of Britain. In support Van Berchem cites the opposition put up by the Helvetii to the Vitellians in 69, the elevation of Aventicum to a colony, and the favour shown it after that by Titus. All this attests connections with Aventicum, not when they were forged, and Helvetian territory did not develop so suddenly under Claudius as to preclude Sabinus from operating there two decades previously.2

The careers of father and son, in the versions of Sabinus’ early life rejected by Suetonius, are suspiciously parallel, military service at just below equestrian level, and then financial enterprises; Pliny the Elder’s History is probably the source for one of them. The point of both versions, illness causing premature retirement, would be the same: he would have become a leading centurion. Both are apologetic. What Suetonius accepts is also interesting. The later financial activities of the son, Sabinus, required capital, which he presumably augmented as a tax-collector in Asia and among the Helvetii. Even though he did not serve in the army, he seems likely, as a man playing a responsible if minor part in the collection of taxes in Gaul, to have reached just below equestrian rank or to have been close enough to pass as an eques. Suetonius’ confidence suggests that he thought that he was using a good source, though evidently not Vespasian’s own memoirs, which dealt with the Jewish War.3

A different purpose lay behind a story about Petro that Suetonius rejects. He claims not to have been able to find any evidence for it – which brings out the obscurity of the family. In this version, Petro’s father came from Transpadane Gaul as a contractor of the farmhands from Umbria who were hired annually in the Sabine territory. In other words, he was a newcomer to Reate, without landed property, and his claim to consideration there was based on his wife being a native; worse, he was a Gaul. This tale was uncovered or developed – the name Petro is certainly Gallic – by a source hostile to Vespasian. It could be oral or written, in the form of a political pamphlet, and belong either to the months between Vespasian’s bid for power on 1 July 69 and the fall of Rome nearly six months later or to scurrility circulating after Vespasian’s accession.4

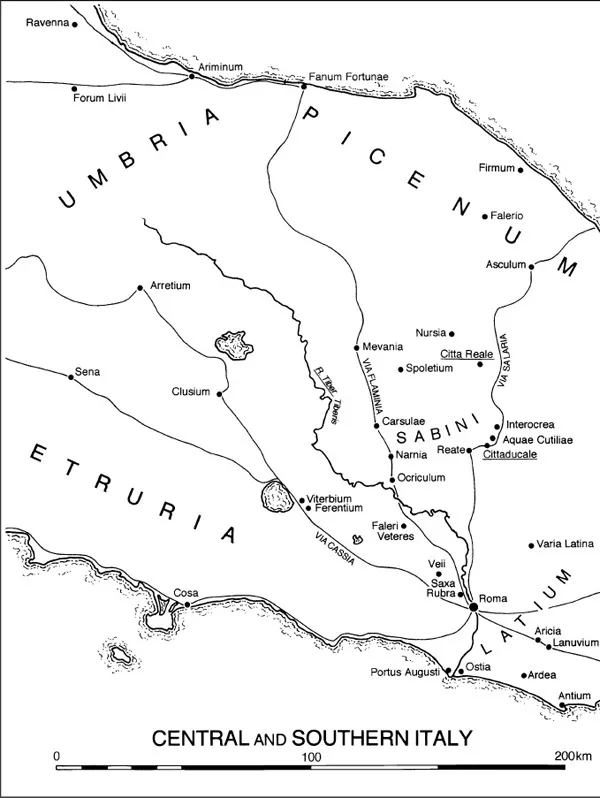

Sabinus married up, something once frowned upon in English society but not worth comment at Rome, as Gaius Marius’ uncontroversial marriage (c. 111 BC) to a Julia of the Caesars shows. Vespasia Polla came from a family eminent at Nursia, an Umbrian town abutting on Sabine territory, and her father Pollio, as well as holding the post of Camp Prefect, served three terms as military tribune, a post for intending senators as well as equites. Suetonius notes a place six miles from Nursia on the road to Spoletium known as ‘Vespasiae’ which showed many sepulchral monuments of her family and proved its distinction. Her brother had entered the senate as one of the propertied men from all over Italy encouraged by Augustus, and reached the praetorship. Not surprisingly, the second son took his cognomen (surname) from his mother.5

The financial activities of Petro and Sabinus are stressed in the opening pages of Suetonius’ biography, but respectable landed property recurs in stories of Vespasian’s forebears and early life. He was brought up on the considerable estates of his paternal grandmother Tertulla at Cosa in Etruria, perhaps while his parents remained in Asia or the Alps. ‘Vespasiae’ may have been the site of another property, and it is possible that Vespasian’s mother also owned a house in Spoletium. These properties belonged, significantly enough, to the families into which the Flavii married. Their own base may have been in the hamlet where Vespasian was born, at Falacrina. A. W. Braithwaite located it thirty-two kilometres along the Via Salaria (Salt Road) on the other side of Reate from Rome: S. Silvestre in Falacrino i Collicelli near Cività Reale preserves the name. Here we may put the home of Sabinus. Another story from Suetonius’ biography seems to provide the family with a residence just outside Rome as well. An ancient oak in the grounds, sacred to Mars, put out shoots on each occasion when Vespasia gave birth. The third, when Vespasian was born, was like a young tree. But the word for his estate, ‘suburbanus’, need not refer to places outside Rome. We are not prevented from seeing the Flavians as small entrepreneurs, marrying into the landed gentry of the Sabine territory, and may even suspect truth in the story of Petro’s father’s origins as a labour contractor.6

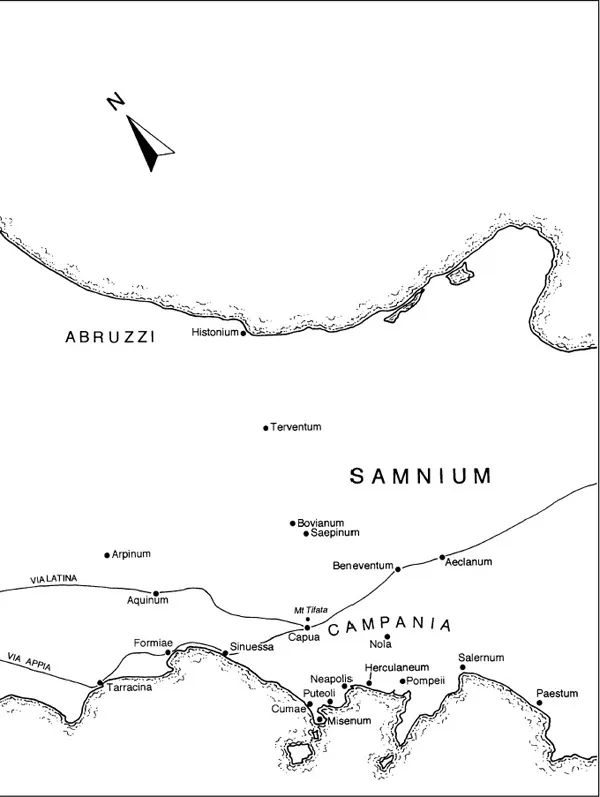

The land from which Vespasian sprang and which gave him his countrified accent was well described by L. Homo – five thousand square kilometres of upland north-east of Rome, surrounded by Etruria in the west, Umbria in the north, Picenum in the east, and the central Italian tribes of the Abruzzi in the south. Only a third was cultivable. Mountainous and forested towards the north (it was known for its acorns), it had more amenable plains surrounding Amiternum and Reate to the south. Cultivation of olive, vine, and herbs, and stock-raising, were the staple occupations. Tough conditions and an early entry into Roman history, illustrated by the tales of the Roman rape of the Sabine women and of Romulus’ sharing of power with the Sabine king Titus Tatius, gave these people a reputation for courage and high morals, as well as entitlement to participate in Roman life at the highest level, as the Claudii had done for centuries. They succumbed to Roman power in 290 BC and received full Roman citizenship twenty-two years later.7

Vespasian would spend summers in this country, on at least one occasion lingering until his birthday in November, or returning to celebrate it. His favourite spot, where he was to die, was Aquae Cutiliae near Cittaducale, close to his birthplace, only twelve kilometres east of Reate towards Interocrea. But he also loved the time he spent on his grandmother’s estate; he kept it as it had been, and would celebrate her memory by using for special occasions, perhaps her birthday, a silver cup she had owned.8

If Vespasian cared so much for his home country and for his family, it would not be surprising if he assumed the manners of his hard-working countrymen and made no secret of what he learnt from his parents and grandparents, as Homo observed. He could not or would not rid himself of his accent, and probably told the truth, or enough of it, about his origins, avoiding pretentious claims such as those of the family of his rival Vitellius (that they were descended from Faunus, king of the Aborigines, and his divine consort Vitellia), which merely provoked the outspoken Cassius Severus into attributing them a very different origin – from a freedman. His own career and principate, combining military achievement with administration that was notably canny over money, recalls the preoccupations of his father and grandfather; his unabashed sense he may have learned from his grandmother Tertulla. One story projects it back on her. When she was informed by his father that the omen of the oak branch, which he had confirmed by inspecting the entrails of a sacrificial animal, showed that her grandchild was born to be a Caesar, she laughed at being still in her right mind when her son had gone senile.9

Vespasian’s mother was ambitious: her sons should reach the status of her brother the ex-praetor, and the combined fortunes of the families provided the census of two senators, 2m HS. Vespasian’s upbringing is unknown, and although in his reign he encouraged education, nothing is said of a taste for literature or philosophy, or of oratorical gifts. Vespasian knew Greek, but it may have been acquired in Achaea or in Judaea, relatively late in his career. All the same, his education must have been adequate, even if his literary attainments were only mediocre.10

Map 1.1 Central and Southern Italy

The elder Flavius applied for the permission to wear the latus clavus (the broad stripe on the tunic), prerogative of members of the senatorial order, in token of his ambitions. No doubt he was supported by his uncle the senator. Vespasian, who must have taken the toga of manhood in 25–6, at the age of sixteen, declined to apply – for a long time, according to Suetonius, and until his mother provoked him into agreement by calling him his brother’s anteambulo, ‘footman’ or ‘dependent’. Perhaps the senator’s sister was particularly ambitious, as Homo suggested, for the son who derived his cognomen from her own name. How long Vespasian’s intransigence really lasted is uncertain: it could have been years, months, or only weeks. The story is of a familiar type: how close a great man was to losing his chance of greatness, but for his mother’s intervention. It could have become known, and from Vespasian’s own mouth, at any time, on his first successes in Britain, at the time of his consulship, at his mother’s death, or when he became Emperor. In the year of his refusal, lack of adequate funds or the desire to follow in his father’s footsteps need not have been the only deterrents: it was the decade in which, since the death of the Tiberius’ son Drusus Caesar in 23, the struggle for the succession became more intense and more dangerous for anyone in politics, with the ascendancy of Tiberius’ minister L. Aelius Sejanus (24–31).11

Aspirants to the quaestorship, the first magistracy that gave membership of the senate, should have two periods of service to their credit: one as tribune of the soldiers, the other in one of the minor magistracies known collectively as the Vigintivirate, the Board of Twenty. As the sons of a non-senator, Sabinus and Vespasian are likely to have held the military post first. Vespasian served in Thrace, a troublesome dependency where disturbances broke out probably in 25 and continued until 26 or even 27; 26 was the year in which the governor of Moesia, C. Poppaeus Sabinus, won triumphal decorations for suppressing them. Vespasian would have been in one of the Moesian legions that were sent to put them down, IV Scythica rather than V Macedonica, since no reference is made to a previous term with V when Vespasian took it for the Jewish War. But he is likely to have arrived in 27, after the main fighting was over, and so to have spent his time on garrison duty. Legionary detachments remained in Thrace after the disturbances ended, and J. Nicols believes that Vespasian spent three or four years in post; a three-year stint would bring him home in 30.12

Vespasian’s post in the Vigintivirate is unknown, but, given his origins, it is not likely to have been one of the more prestigious of the four posts, those of the three-man board of masters of the mint or of the ten men with judicial functions (IIIvir momtalts; Xvir stlitibus iudicandis): even under Augustus most moneyers came from families bearing senatorial names or at least had forebears who had held the same post. He was probably either one of four men in charge of street cleaning in the city or, worst, one of the three who supervised executions and book-burnings (IVvir viarum curandarum; IIIvir capitalis). The street-cleaning post gives no clue when it might have been held; but if Vespasian served as capitalis in 31, he would have shared responsibility for carrying out the most notorious executions of the early Principate: those of Tiberius’ fallen minister Sejanus on 19 October, and of his children, strangled in November or December and exposed on the Gemonian Stairs. Those deaths were remembered with horror, as Tacitus’ account of them shows. If Vespasian had a part in this or in the subsequent witch-hunt, which culminated in 33 with what Tacitus called ‘a massacre of enormous proportions’ – the execution of twenty of Sejanus’ associates – it would have been exploited in the propaganda war of 69 or by dissident circles during Vespasian’s principate. We hear nothing. Either Vespasian served before Sejanus’ fall, in 30, or he held the innocuous IVvirate, which would have been a natural step towards his later aedileship.13

Once over the Vigintivirate, Vespasian was entitled to stand for senatorial office proper, the quaestorship, on which he could have entered on 5 December 33 at the age of just twenty-four, but he may have waited, held office in 34–5, one year after his brother, or 35–6. As quaestor it was only to be expected that he should receive one of the (less prestigious) provincial posts, whose holders acted as financial assistants to the governors of public provinces, the proconsuls. Theirs were the least sought after of the twenty postings available. It was Crete with Cyrene that fell to Vespasian, ‘by the lot’, but the high-grade positions that kept young men at Rome as assistants to the consul or to the Emperor himself must have been given before the provincial posts were drawn; Vespasian’s province was not even one of the two in which the quaestors served under proconsuls who had actually held a consulship, Asia and Africa: Crete with Cyrene, like Bithynia and Narbonensian Gaul, was governed by an ex-praetor, who might never reach the consulship and so be able to help on a young subordinate. The functions of the provincial of...