![]()

1 A young author’s ideal illustrators

Stevenson’s first illustrated novel was published in 1884 in America, with four illustrations that he would later complain were “disgusting”.1 The novel was Treasure Island, which had been previously published in serial format in the boys’ magazine Young Folks Paper with one illustration; the artist referred to unceremoniously was Frank T. Merrill, who had gained a reputation in America as an illustrator of novels by, among others, Nathaniel Hawthorn, Mark Twain and Louisa May Alcott. The first European illustrated edition of Treasure Island was published in 1885 by Cassell and Co., using illustrations by the French artist Georges Roux, whose style of illustration was much more to Stevenson’s liking. In fact, as this book will demonstrate, Stevenson had clear and evolving ideas about the importance of suitable illustration of his novels, and that he was keen to marry his texts to imagery that would entice the reader, reflect and compliment his texts in the appropriate manner, and produce an attractive physical object for the purchaser. The problem lies in defining what Stevenson defined as “suitable” and “appropriate” illustration. This is further problematised by the vast array and long history of illustrated texts that had proliferated by the time Stevenson was publishing his novels. By the 1880s, there were many theories, practices and innovations within the field of illustrated literature, and there were many disagreements about its application and suitability for “serious” or high literature. The 1890s, in particular, saw the Arts and Crafts Movement of William Morris, Walter Crane and Aubrey Beardsley create sumptuous illustrated books that were heavily designed from cover to cover, almost making the text a facet of the books’ designs. At the same time, “children’s” illustrators were earning a reputation of their own: they were revered, publically and critically, but not considered as serious artists so much as highly skilled popular draughtsmen and women, interpreters of texts and trusted purveyors of popular culture and taste. Stevenson admired this latter group, which included luminaries such as Randolph Caldecott, Kate Greenaway and, in America, Howard Pyle. These artists in particular were attempting to marry imagery and text of their own composition, in addition to creating illustrations for famous authors of the day and great authors of the past. Stevenson did not necessarily see popular and high art as mutually exclusive; for him, a good story published for the masses in illustrated format could achieve the status of great art if appropriately conceived. Indeed, his novels tread this fine line between high art and popular entertainment, and his reputation as a serious artist has been threatened through popular interpretation as a consequence; we need only to consider the multifarious cinematic and television treatments and derivatives of Treasure Island and Jekyll and Hyde to appreciate this phenomenon.

However, it was precisely this marriage of high art and popular entertainment which led to Stevenson’s conception of a new visual discourse in illustrated literature: popular fiction of high artistic merit, illustrated by talented artists in a manner that would enhance the romance of the texts they adorned. As Stevenson understood, any visual interpretation of his work by an artist other than himself meant losing a level of aesthetic control over his creation. Visualisation by a third party is, to a greater or lesser extent, an adaptation, or appropriation of the author’s original vision; the illustration of the original novels is the point at which these adaptations begin.2 The end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth saw the ever increasing proliferation of illustrated literature that directly prefigured and influenced the cinematic age. It is essential, therefore, to understand how the authors themselves wanted their work illustrated, and, if possible, to glean how they themselves might visualize their own characters and settings. This is a difficult task given the breadth and depth of illustrative styles during this period. In between the designs of the Pre-Raphaelites, on the one hand, and the popular illustrated children’s fiction of Caldecott and Greenaway on the other, was a vast array of illustrative treatment of creative writing, much of which Stevenson was highly wary. By the 1880s, there were many different methods of printing and reproducing imagery, which had evolved from copper-plate engraving at the beginning of the century, through steel-plate engraving, wood-block and wood-engraving, lithography and various forms of photographic reproduction. Late Victorian Britain was awash in illustrated literature, and illustration of texts heavily influenced the interpretations of those texts by children and adults alike. While Stevenson was versed in many of the aspects of contemporary book illustration, his tastes for the illustration of his own work tended towards the more figurative, narrative style that can be traced back through the Hogarth-inspired works of George Cruikshank, Halbot Browne (Phiz), William Makepeace Thackeray and the illustration of Walter Scott’s Waverley novels. It is important to understand an essential difference in the role of illustration here: where the Kelmscott artists and publishers, for example, used illustration to decorate books, Stevenson wanted illustration to emphasize and elucidate narrative; in other words, illustration for Stevenson served his stories, and should never be merely decorative of the page. This chapter will discuss the earliest illustrations of Stevenson’s published works, particularly those of the children’s illustrator Walter Crane. In doing so, it will help to elucidate Stevenson’s priorities and tastes in the illustration of his work from the beginning of his career as a writer, from both an artistic and a professional perspective. It will end with a discussion of another crucial type of illustration that is indelibly linked to Stevenson’s oeuvre: maps. Maps were important visual stimuli to Stevenson’s creative imagination; moreover, in at least two instances, they become significant in not only illustrating the stories being told, but also in transforming the novels into interactive objects of recreation, or toys. This aspect of Stevenson’s literary-visual discourse would have a great influence on a subsequent generation of adventure and children’s writers, from Rider Haggard and J. M. Barrie, through Rudyard Kipling and J. R. R. Tolkien.

Walter Crane’s frontispieces

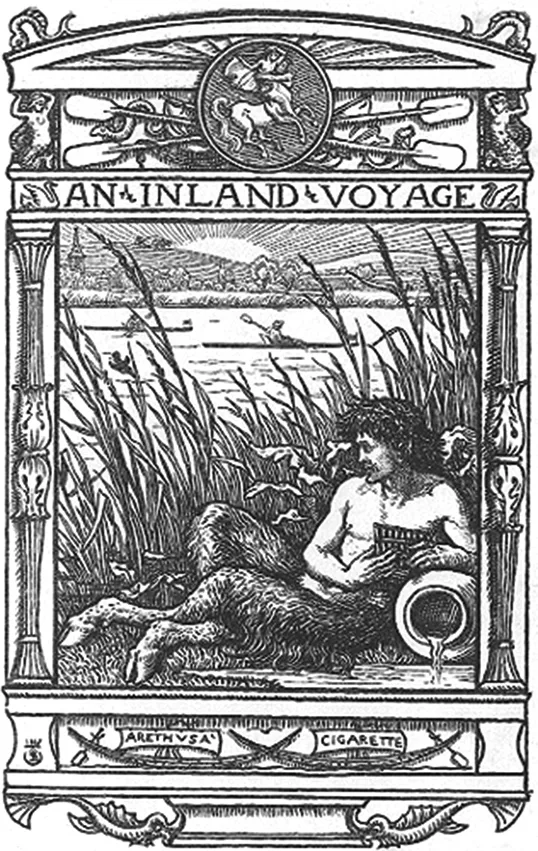

The three foremost children’s illustrators of the 1870s, Walter Crane, Randolph Caldecott and Kate Greenaway, would all be approached to illustrate Stevenson’s earliest works. In 1878, the year in which Stevenson was attempting to publish his first book-length work, An Inland Voyage, Crane’s was the most sought-after talent, being the most senior and experienced illustrator for Edmund Evans’s series of “toy books”. It is therefore of some significance that he was successfully recruited to illustrate An Inland Voyage in its first edition, years before Stevenson would achieve his fame. Crane cuts a curious figure in the subject of Stevenson illustration. He was Stevenson’s very first book-illustrator, providing the wood-cut frontispiece plate for An Inland Voyage, an artful travelogue recording a canoe trip up the River Oise through Belgium and France taken by Stevenson (Arethusa in the narrative) and his friend Sir Walter Grindley Simpson (Cigarette).3 When he provided this image, Crane was doing Stevenson and his publisher, Kegan Paul, a favour; Stevenson was an aspiring author of some critical but no popular success, while Crane was one of the most accomplished and famous illustrators of the day. Stevenson’s anxiety that Crane’s name appear in the title-page is revealed in a letter of 16 March 1878, in which he politely begs Crane to produce the illustration for the publisher as soon as he can:

You have written to him promising a frontispiece for a fortnight hence for a little book of mine—An Inland Voyage—shortly to appear. Mr Paul is in dismay. It appears that there is a tide in the affairs of publishers which has the narrowest moment of flood conceivable: a week here, a week there, and a book is made or lost; and now, as I write to you, is the very nick of time, the publisher’s high noon.

I should deceive you if I were to pretend I had no more than a generous interest in this appeal. For, should the public prove gullible to a proper degree, and one thousand copies net, counting thirteen to the dozen, disappear into its capacious circulating libraries, I should begin to perceive a royalty which visibly affects me as I write.

I fear you will think me rude, and I do mean to be importunate. The sooner you can get the frontispiece for us, the better the book will swim, if swim it does.4

Stevenson’s anxiety that the book “swim” in the market is a familiar refrain of aspiring authors who are dependent upon others for the successful publication of their first major work. Before the publication of Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde in 1886, Stevenson’s name alone might not have been enough to move large numbers of a travel journal. In this case, Crane’s name and work would be an asset to the sale of An Inland Voyage.

However, this did not stop a young Stevenson (28 when he wrote to Crane) from privately critiquing and criticising the proof-design Crane had produced for the volume. In a letter dated 27 February 1878, before he writes to Crane above, Stevenson writes to Sidney Colvin to offer a critical comment on Crane’s initial design: “I think you know all about the Crane sketch; but it should be a river, not a canal, you know, and the look should be ‘cruel, lewd, and kindly’, all at once’”.5 This is a reference to specific lines in his essay “Pan’s Pipes”, first published in London, on 4 May 1874, and republished in Virginibus Puerisque, in which he writes, “For it is a shaggy world, and yet studded with gardens; where the salt and tumbling sea receives clear rivers running from among reeds and lilies; fruitful and austere; a rustic world; sunshiny, lewd, and cruel”.6 The final illustration seems to have followed the author’s suggestion, as Pan is depicted sitting luxuriantly among the reeds, hidden “lewdly” from two canoes in a large river behind, which carry the two protagonists on their voyage up the Oise River (Figure 1.1).

Stevenson’s critical comments and his personal address to Crane may seem presumptuous, even arrogant, given his age, comparative inexperience and his low profile. However, retrospectively it provides evidence of an already acute critical appreciation of the power of illustration either to mould or usurp a text. On picking up his book, Stevenson understood that a cursory glance at the illustration inevitably shapes both reader curiosity and expectation. If Crane’s image depicted a canal, the reader would expect the book, naturally, to describe a journey on a canal, and would be confused by the subsequent narrative of a journey up a large river. Such variance would raise questions for the reader: who is in charge, author or illustrator; which is the dominant medium, text or image; should we trust Crane, whom we’ve heard of, or Stevenson, of whom we have not? None of these questions may seem particularly important to the casual reader, but when text and illustration deviated in this way, the book, as a cohesive work of art, failed for Stevenson. As Chapter 2 will demonstrate, text and image, author and illustrator, had to be working towards a common artistic vision, a vision which in a literary text had to be defined by the author.

A close examination of the frontispiece provides affirmation of Crane’s talent as an illustrator of others’ texts. Crane took as his inspiration Stevenson’s allusion to Pan in the chapter “The Oise in Flood”. In this chapter, the author is enjoying the apparently serene but fast-moving flow of the swollen river in the Arethusa when, coming round a corner, he is caught by a low-hanging tree and lifted into the air, while his canoe carries on downstream without him. This semi-comical episode becomes a musing on the theme of the myth of Pan, who’s playing often leads us into dangers we do not see. Stevenson draws a comparison between the beauty of the wind playing in the reeds by the side of the river, and the “terror” it produces in the river’s animal life, which can read in this sign the portents of the swollen and fast-flowing waters:

Figure 1.1 Walter Crane, frontispiece for An Inland Voyage (1878).

There should be some myth (but if there is, I know it not) founded on the shivering of the reeds. There are not many things in nature more striking to man’s eye. It is such an eloquent pantomime of terror; and to see such a number of terrified creatures taking sanctuary in every nook along the shore, is enough to infect a silly human with alarm. Perhaps they are only a-cold, and no wonder, standing waist-deep in the stream. Or perhaps they have never got accustomed to the speed and fury of the river’s flux, or the miracle of its continuous body. Pan once played upon their forefathers; and so, by the hands of his river, he still plays up...