![]()

1 The conundrum of Chinese agriculture

Jan Douwe van der Ploeg and Ye Jingzhong

There are several important reasons for examining and trying to understand Chinese agriculture. It is, to begin with, the largest ‘agricultural system’ in the world: it ranks number one globally in terms of farm output and embraces over 200 million smallholdings.1 With just 10 per cent of all cultivated land in the world, these smallholders produce 20 per cent of the world’s total food supply. This suggests that China’s agriculture performs exceptionally well. Yet, we should be aware that if something were to go wrong in this agricultural system the consequences would be catastrophic. China’s agriculture also stands out for its impressive development over recent decades. Production and productivity have grown continuously and this growth has gone hand in hand with an equally impressive alleviation of rural poverty. This suggests that the example of China’s agriculture might also have a relevance beyond the country’s boundaries, particularly in places where productivity has failed to keep up with population growth but also in other places where agriculture has reached an impasse. As implausible as this may first sound, it might also help to highlight some of the changes that are badly needed in agriculture in ‘developed countries’. However, it is far from easy to understand the nature, dynamics and drivers of China’s agriculture.

Coming to grips with Chinese agriculture requires a threefold inquiry. That is why it is so difficult and, from an intellectual point of view, so attractive. First comes the empirical inquiry into Chinese agriculture. What are its main structural components? What are the rates of growth in production and productivity? What are the main institutions? Questions like these are far from easy to answer, partly due to the immense size of rural China and to its impressive heterogeneity. It is especially difficult because it requires the understanding of something the academic world generally misrepresents or even ignores: the peasantry.

Examining the performance of China’s agriculture almost automatically provokes a second line of inquiry. How has it been able to generate such unprecedented growth in production and productivity? How could it possibly perform in this way? When looked at from a Western perspective, China’s agricultural performance appears almost impossible. From the Western paradigm of agricultural development2 the accomplishments of Chinese agriculture appear to be structurally impossible. As such, rural China is an anomaly, a seeming deviation from the standard pattern – a deviation that conventional thinking would consider as doomed to failure, but which, in practice, is a remarkable success. There are several theoretical reasons why the Western paradigm views Chinese agriculture as destined to fail. First, the farms are far too small: the average holding is only 5 mu of land (one-third of a hectare). That is microscopic, not only from an American point of view, but even from a European or Dutch perspective.3 The average Chinese farm is too small to provide an acceptable income, let alone allow for savings. And without savings there cannot be investments, thereby excluding the possibility of developing the farm. In addition, there is massive rural outmigration. It is estimated that currently at least 200 million people, mostly men, move every year from rural to urban areas. The result is that only women and the elderly remain to do the agricultural work. Many experts perceive such a pattern as intrinsically weakening agriculture (UNDP, 2003; Peterman et al., 2010) – the outflow of so many men certainly does not help strengthen agriculture. As long ago as the late 1980s Lester Brown wrote an essay entitled ‘Who will feed China?’. This title perfectly reflects the chasm separating the Western view and Chinese reality. We now know the answer to the question raised by Lester Brown. With a few exceptions, notably soy imports, China is feeding itself. And it does so in a proud and convincing way. China is now an important point of reference when it comes to debates about food and farming.4 It is this that triggers the second inquiry: How is the seemingly impossible achieved? Put differently, how is the Western paradigm blocking (or blatantly distorting) our understanding of what is happening in China? In short, a serious inquiry into Chinese agriculture necessarily translates into a second inquiry that critically probes the dominant Western paradigm – an inquiry that needs to identify and challenge the seemingly self-evident ‘lenses’ that would, left uncorrected, strongly bias our understanding of what agriculture is and how it works.

Together, these two inquiries flow into a third one that focuses on the why. It centres on the reasons that positively explain the remarkable, but at first sight highly unlikely, performance of China’s agriculture. Among the major ingredients that together explain the enigma are the peasant nature of China’s agriculture, the circularity of town–countryside relations, the horizon of relevance used in agricultural research and development (which differs remarkably from the one used in Western agricultural sciences), the recent turn in the urban bias5 and the omnipresence of markets. This last ingredient might surprise many readers. According to the Western view, Western agriculture is market-oriented and Western society is governed by markets (especially in this neo-liberal epoch). However, we should not forget that in reality the ‘market’ in the West is merely a front for large corporations and supermarkets that control the many transactions that bring goods and services from producers to consumers. ‘Real’ market-places, where many buyers meet many sellers and where an ‘invisible hand’ defines prices, volumes and flows, have been in decline for several decades and are now far from the main locus of transactions (Winders, 2009). By contrast, in China they are abundant – and this has an undeniable and positive impact. This will be discussed at some length in this book, alongside the effects of the other ingredients.

When properly combined and integrated the ingredients that emerge out of the third inquiry may carry an important promise. They can be used to delineate the contours of an alternative paradigm that may also be helpful in other parts of the world. They can offer new, unexpected solutions and help spotlight new empirical realities that have largely remained unnoticed. In short, this alternative (or ‘Chinese’) paradigm can be very helpful for those working in other situations.

Small-scale, but booming

When travelling through China one crosses, every now and then, huge plains that go from one horizon to the other, completely covered by grain crops. As extensive as these plains are, they are made up of tens of thousands of small fields, each tilled by a peasant family having on average 5 mu of land. Together they produce amazing amounts of grain. As already mentioned, from the Western perspective such units are viewed as too small to provide an income. As such, the peasant family should be living in poverty and trying everything it can to find job opportunities elsewhere and, having secured these, the family would probably dedicate less time and attention to the land or maybe even leave it lying barren. Even if all this were not the case, the unit would be too small to allow for profits, savings and subsequent investments. And with no investments being made, stagnation is the inevitable outcome. Nonetheless, while the average Chinese unit of agricultural production is very small, it also shows continuous growth and development. Elsewhere in this book we will try to unravel this conundrum, but here we wish to explore its broader paradigmatic aspects.

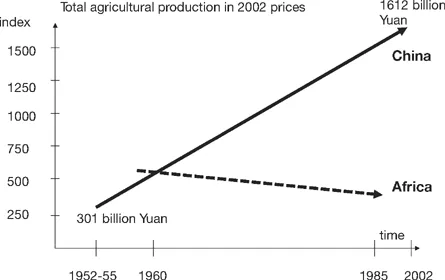

The exceptional nature and dynamics of China’s agriculture clearly come to the fore when we compare it to agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). As shown in Figure 1.1, China has achieved an impressive agricultural growth over the past 60 years. In constant prices (that is, after adjustment for inflation) the total value of agricultural production increased fivefold between the mid-1950s and the early 2000s (data derived from Li et al., 2012). Since the early 1980s both production and total factor productivity have kept growing at a rate unparalleled elsewhere. Over the same period Africa showed a stagnation and decline. Production per capita has continually decreased over successive decades. Nearly three decades ago Mahmood Mamdani (1987) referred to the lack of an agricultural revolution as explaining this chronic stagnation. Whatever the reason for Africa falling behind, China has experienced remarkable agricultural growth. China and its agricultural trajectory diametrically differs from that of Africa.6

The ongoing growth in China’s agriculture has occurred alongside impressive poverty alleviation, which again is in remarkable contrast with what has happened in SSA. As shown in Figure 1.2, poverty has been greatly reduced in China, in both absolute and relative terms. Both the rate and the amount of poverty alleviation are unique. Gulati and Fan (2007:17) refer to this it as ‘an unprecedented achievement in the history of development of any country’. By contrast, in SSA poverty is ‘a persistent headache’ (Li et al., 2012:1) or, as Henley and van Donge (2013:28) put it, ‘it [i.e. poverty] is still the norm’. In relative terms poverty has remained at more or less the same level over recent decades. In absolute terms though, the number of those in poverty has nearly doubled: it went from 167 million in the early 1980s to 298 million in 2004. Today in China poverty is a phenomenon that is limited to specific groups such as abandoned, elderly or disabled people. In this respect China is again diametrically different from Africa.

Figure 1.1 Agricultural growth patterns in China and Sub Saharan Africa (adapted from Li et al., 2012)

There is, however, a clear downside as well. The rapid development of Chinese agriculture is, to a degree, built on decay. First, it is grounded on ecological decay. Extensive ecosystems have been negatively affected – sometimes in an irreversible way: sweet water aquifers are being exhausted and there is extensive contamination due to the widespread use of agro-chemicals (Rampini, 2005 and Zhang et al., 2015). All this has allowed for quick gains in production and productivity, but at a very high price – one that may very well block future development. Massive attempts have been made to reverse these negative tendencies and to repair at least some of the damage. Whether this is possible remains to be seen. Second, there is socio-cultural decay: achieving these impressive growth rates has brought tremendous hardship for the many millions involved. For the ‘left behind’ women and elderly who had to take over most of the work in farming and for the children who do not see their fathers for long periods (Ye et al., 2013). The same socio-cultural decay makes farming appear extremely unattractive in the eyes of many youngsters, which evidently threatens the long term continuity of farming itself. The hardship and suffering of men should also be mentioned. They temporarily migrate from their villages to the towns and industries in order to gain the money needed to finance the growth of agriculture and to maintain their families. In doing so, they often have to face dangerous working conditions, long working days, insecurity about pay and, last but not least, solitude. Third, there is demographic decay. Although peasant families were allowed to have two children, demographic development has produced (in combination with the hardship of country life) an enormous risk for the near future: will there still be people to engage in farming? Finally, there is a fourth form of decay – a form that extends to and...