- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Interfaces of Performance

About this book

This collection of essays and interviews investigates current practices that expand our understanding and experience of performance through the use of state-of-the-art technologies. It brings together leading practitioners, writers and curators who explore the intersections between theatre, performance and digital technologies, challenging expectations and furthering discourse across the disciplines. As technologies become increasingly integrated into theatre and performance, Interfaces of Performance revisits key elements of performance practice in order to investigate emergent paradigms. To do this five concepts integral to the core of all performance are foregrounded, namely environments, bodies, audiences, politics of practice and affect. The thematic structure of the volume has been designed to extend current discourse in the field that is often led by formalist analysis focusing on technology per se. The proposed approach intends to unpack conceptual elements of performance practice, investigating the strategic use of a diverse spectrum of technologies as a means to artistic ends. The focus is on the ideas, objectives and concerns of the artists who integrate technologies into their work. In so doing, these inquisitive practitioners research new dramaturgies and methodologies in order to create innovative experiences for, and encounters with, their audiences.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Creative Media: Performance, Invention, Critique

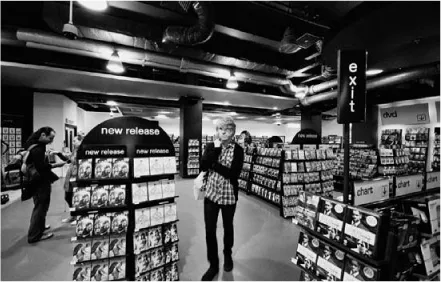

Figure 1.1 Media Spaces 01

Source: Photo – Joanna Zylinska.

Performing a new paradigm

The discussion that follows is an attempt to enact a different mode of doing critical work in the arts and humanities. It adopts the format of a ‘live essay’, performed in (at least) two voices, via numerous exchanges of electronic traces, graphic marks, face-to-face utterances and corporeal gasps. This format is aimed at facilitating collaborative thinking and dialogic engagement with ideas, concepts and material objects at hand between the chapter’s authors, or rather conversational partners. Our direct entry point into the discussion lies with what we are calling a ‘creative media project’. It will provide a focus for our broader consideration of issues of cross-disciplinary performance in this piece.

By giving a name to a set of concerns that have preoccupied us both for a long time, we are performatively inaugurating this creative media project. The project arises out of our shared dissatisfaction with the current state of the discipline of ‘media studies’, within which, or rather on the margins of which, we are both professionally situated. In its more orthodox incarnation as developed from sociology, politics and communications theory, media studies typically offers analyses of media as objects ‘out there’ – radio, TV, the internet. Mobilizing the serious scientific apparatus of ‘qualitative and quantitative methodologies’, it studies the social, political and economic impact of these objects on allegedly separable entities such as ‘society’, ‘the individual’ and, more recently, ‘the globalized world’. What is, however, lacking from many such analyses is a second-level reflection on the complex processes of mediation that are instantiated as soon as the media scholar begins to think about conducting an analysis – and long before she switches on her TV or iPod.

What does our creative media project have to do with performance? Through instantiating this project, we are making a claim for the status of theory as theatre (there is an etymological link between the two, as Jackie Orr points out1), or for the performativity of all theory – in media, arts and sciences, in written and spoken forms. We are also highlighting the ongoing possibilities of remediation across all media and all forms of communication. From this perspective, theatre does not take place – and never did – only ‘at the theatre’, just as literature was never confined just to the book, or the pursuit of knowledge to the academy. What is particularly intriguing for us at the moment is the ever-increasing possibility for the arts and sciences to perform each other, more often than not in different media contexts. Witness the theatre that involved the mediation of the Big Technoscience project in September 2008: the experiment with the Large Hadron Collider at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN). The Hadron Collider is a particle accelerator used by physicists to study the smallest existing particles, and it promises to ‘revolutionise our understanding, from the minuscule world deep within atoms to the vastness of the Universe’ via the recreation of the conditions ‘just after the Big Bang’.2 Rarely, since the Greeks, has such an attempt to stage metaphysics been undertaken with an equal amount of pathos and comedy, with satellite TV networks staging the event for the worldwide audiences in real time. Performances of this sort often incorporate their own meta-narratives, or critiques -although these critiques tend to remain latent or unacknowledged. Remediating such events via critical and creative intervention, the creative media project we have in mind has the potential to become a new incarnation of the age-old ‘theatre-within-the theatre’ device, whose actors are also at the same time critics.

Figure 1.2 Media Spaces 02

Source: Photo – Joanna Zylinska.

For Judith Butler, when drawing on Foucault’s work, the critic

has a double task, to show how knowledge and power work to constitute a more or less systematic way of ordering the world with its own “conditions of acceptability of a system”, but also “to follow the breaking points which indicate its emergence”. So not only is it necessary to isolate and identify the peculiar nexus of power and knowledge that gives rise to the field of intelligible things, but also to track the way in which that field meets its breaking point, the moments of its discontinuities, the sites where it fails to constitute the intelligibility for which it stands.3

Taking seriously both the philosophical legacy of what the Kantian and Foucauldian tradition calls ‘critique’, and the transformative and interventionist energy of the creative arts, creative media can therefore perhaps be seen as one of the emergent paradigms at the interfaces of performance and performativity that this volume is trying to map out. What will hopefully emerge through this process of playful yet rigorous cross-disciplinary intervention will be a more dynamic, networked and engaged mode of working on and with ‘the media’, where critique is always already accompanied by the work of participation and invention.4

Repetition with a difference

One of the reasons for our interest in developing such a creative media project is our shared attempt to work through and reconcile, in a manner that would be satisfactory on both intellectual and aesthetic levels, our academic writing and our ‘creative practice’ (photography in Joanna’s case, fiction in Sarah’s). This effort has to do with more than just the usual anxieties associated with attempting to breach the ‘theory-practice’ divide and trying to negotiate the associated issues of rigour, skill, technical competence and aesthetic judgement that any joint theory-practice initiative brings up. Working in and with creative media is for us first and foremost an epistemological question of how we can perform knowledge differently through a set of intellectual-creative practices that also ‘produce things’. The nature of these ‘things’ – academic monographs, novels, photographs, video clips – is perhaps less significant (even though each one of these objects does matter in a distinctly singular way) than the overall process of producing ‘knowledge as things’. In other words, creative media is for us a way of enacting knowledge about and of the media by creating conditions for the emergence of such media. Of course, there is something rather difficult and hence also frustrating about this self-reflexive process – it is supposed to produce the thing of which it speaks (creative media), while drawing on this very thing (creative media) as its source of inspiration – or, to put it in cybernetic terms, feedback.

But this circularity is precisely what is most exciting for us about the theory of performativity and the way it has made inroads into the arts and humanities over the last two decades. Drawing on the concept of performativity taken from J.L. Austin’s speech-act theory as outlined in his How to Do Things with Words, thinkers such as Jacques Derrida and Judith Butler have extended the use of the term from being limited to only exceptional phrases that create an effect of which they speak (such as ‘I name this ship Queen Elizabeth’ or ‘I take this woman to be my lawful wedded wife’) to encapsulating the whole of language.5 In other words, any bit of language, any code, or any set of meaningful practices has the potential to enact effects in the world, something Butler has illustrated with her discussion of the fossilization of gender roles and positions through their repeated and closely monitored performance. Performativity is an empowering concept, politically and artistically, because it not only explains how norms take place but also shows that change and invention are always possible. ‘Performative repetitions with a difference’ enable a gradual shift within ideas, practices and values even when we are functioning within the most constraining and oppressive socio-cultural formations (we can cite the Stonewall riots of 1969, the emergence of the discipline of performing arts, or the birth of the Solidarity movement in Poland in 1980 as examples of such performative inventions). With this project, we are thus hoping to stage a new paradigm not only for doing media critique-as-media analysis but also for inventing (new) media.

Figure 1.3 Media Spaces 03

Source: Photo – Joanna Zylinska.

Creative media: A manifesto of sorts

Put boldly, our contention is that conventional forms of media analysis are ineffective in as far as they are based on what we perceive to be a set of false problems and false divisions. The false problems involve current conceptions of interactivity, convergence, determinism, constructionism, information and identity. False divisions, which continue to structure debates on new media in particular, include those between production and consumption, text and image, and language and materiality. We also maintain that there is no rigid division between new and old media, as ongoing processes of differentiation are constantly taking place across all media. The underlying problem of ‘the media’ is precisely that of mediation; of the processes – economic, cultural, social, technical, textual, psychological – through which a variety of media forms continue to develop in ways which are at times progressive and at times conservative.

The problem of mediation is for us both contextual and temporal. It centres on the evolution of media in a wider socio-economic context. The role of technology in this process of evolution is neither determining nor determined. Indeed, this role is never ‘merely’ instrumental or anthropological, as Heidegger argues: it is rather vital and relational. If the essence of technology is inseparable from the essence of humanity, then there is no justification for positing humanism against technicism, or vice versa. There is also no point in fighting ‘against technology’. But there is every point – or, indeed, an ethico-political injunction – to exploring practices of differentiation at work in the current mediascape. Our creative media project seeks to promote the invention of different forms of engagement with media. This is not to say that differentiation is always welcome and beneficial, and that all forms of difference are to be equally desired, no matter what material and symbolic effects they generate. Our emphasis is on creative/critical practices which are neither simply oppositional nor consensual, and which attempt, in Donna Haraway’s words, to ‘make a difference’ within processes of mediation. To put this another way, we are interested in staging interventions across conventional boundaries of theory and practice, art and commerce, science and the humanities. Such interventions may come to constitute events that cannot be determined a priori.

Figure 1.4 Media Spaces 04

Source: Photo – Joanna Zylinska.

The invention of what (and what for)?

Of course, not all events are equal, and not everything that ‘emerges’ is good, creative or even necessarily interesting. Far from it. Mediation, even if it is not owned, dominated or determined economically, is heavily influenced by economic forces and interests. This state of events has resulted in the degree of standardization and homogenization that we continue to see across the board: witness the regular ‘inventions’ of new mobile phones or new forms of aesthetic surgery. The marketization of creativity ends up with more and more (choice) of the same – even if some of these ‘inventions of the old’ can at times be put to singularly transformative uses. And yet most events and inventions are rather conservative or even predictable; they represent theatre-as-we-know-it. Our own investment lies in recognizing and promoting ‘theatre-as-it-could-be’ (the phrase is adapted from Chris Langton’s founding definition of artificial life, a discipline that manages both to draw on the most conventional metaphysical assumptions about science and life, and to open a network of entirely unpredictable possibilities for imagining ‘an otherwise world’6). We are interested in witnessing or even enacting the creative diversification of events as a form of political intervention against this proliferation of difference-as-sameness. We find such ‘non-creative’ diversification everywhere, including in the increasingly market-driven academy. One can easily blame ‘performance audits’ such as the Quality Assurance Agency’s inspection visits and the Research Assessment Exercise in the UK, or the compiling of international university league tables for the standardization and homogenization of the academic output worldwide. But these ‘quality-enhancement’ procedures are just a means to the end of competition and survival within an overcrowded global market, run on an apparently Darwinian basis whereby size (of institution) and volume (of output) really do matter.

In this kind of environment, it is sometimes very difficult to make a difference. But we can remind ourselves here of Haraway’s willingness to recognize the real limitations of a politics she referred to as cyborg politics. In that old, seem...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Digital Research in the Arts and Humanities

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Series Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Creative Media Performance, Invention, Critique

- Part 1 Environments

- Part 2 Bodies

- Part 3 Audiences

- Part 4 Politics

- Part 5 Affect

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Interfaces of Performance by Maria Chatzichristodoulou,Janis Jefferies in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.