![]()

Part I

The spatial dimension of knowledge development

In this part we present chapters that give insight into both the institutional set up of Norwegian regions, as part of what we later in the book discuss as The Norwegian Model, and a discussion of concepts that can help us understand knowledge development in the region. The chapters aim to describe regional practice. They also aim to influence and change practice; however, we emphasise here their descriptive dimension. This part of the book will help the reader understand some of the institutional set-up and processes of knowledge development that we find in a Norwegian region. All four chapters in this part make comparison to other regions of geographical areas.

Chapter 1: Developing a sustainable business model in a changing economy presents the regional paradigm. It divides applied research into three types: commissioned, contributory and participatory. It demonstrates how regional research institutes receive both contributory and commissioned funding, thus developing applied research in general, as well as contract research. The chapter also demonstrates how academic credibility has become more important in applied research.

Chapter 2: Why Norway has to develop its own innovation policy argues that the region can be understood in different ways in terms of modes of innovation. This calls for a contextualised understanding of innovation, on how research can support innovation. The main argument is that Norway in general has a more learning mode of innovation than found in other countries that rank high in innovation indexes. This is partly due to the fact that incremental, learning and social trust and interaction are difficult to measure in international rankings.

Chapter 3: Knowledge transfer in different regional contexts tries to develop a typology of regional institutional setups. It divides between institutional thin and thick regions and diverse or specialised regional innovation systems (RIS). It connects this to forms of knowledge exchange, where there is a divide between static and dynamic, and between formal and informal. This typology places Agder in the category of thick and specialised regional innovation system.

Chapter 4: Collective knowing argues that regional innovation is a matter of collective knowing. Based on cases from Spain and from Agder, Norway, the argument is that knowledge development happens as a process over time and is dependent on building trust and developing a common language.

![]()

1 Developing a sustainable business model in a changing economy

Roger Henning Normann, Eugene Guribye and Kristin Wallevik

Norwegian research infrastructure

Norwegian research institutes are important participants in the research infrastructure, and have a special role in applied research. The Research Council of Norway (RCN) states that the research institutes should offer research of high quality and relevance for utilisation in industry and commerce, public administration and society in general. In order to ensure that these institutes fulfil the social task they have been given, they are measured according to four main criteria:

1 relevance to society

2 scientific quality

3 competitiveness

4 structure.

The research market has become highly competitive, where research institutes now experience combined pressure from universities and consulting firms, in addition to other regional, national and international institutes. In this landscape, it is critical to define and develop a sustainable business model to remain competitive. We address issues related to this development and discuss how regional research institutes may adapt to new market challenges.

In the 1970s, a number of university colleges were established outside the major cities in Norway. This was part of a regional policy aiming at decentralising education and hence, covering the need for education and competence in all regions. Subsequently, a number of regional research institutions were established adjacent to these university colleges, with financing from the authorities. By making research competence available to academic communities outside the major cities, the authorities enabled a research focus on regional commercial, political and social issues. Consequently, the regional research institutes tended to specialise in areas of a specific regional interest. They were considered to be important contributions to regional development. Most regional research institutes are younger than the national research institutes, and have established new research communities in collaboration with similarly smaller university colleges. These regional institutes have been compelled to develop without the support of the long-existing scientific and academic traditions which the national institutions in the major cities have. In this early phase, most of the institutes were financed by national and regional authorities, both general financing of institutional activities and project financing. This provided financial predictability.

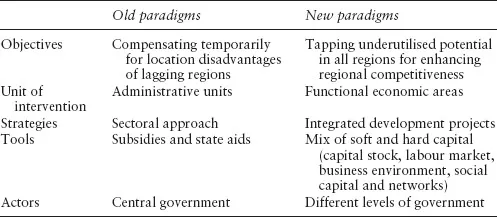

In the 1990s, RCN’s regional policy was the driving force in the further development of the regional research institutes.1 This regional policy is based on a notion that distribution of knowledge is a fundamental driver for innovation. Furthermore, it is also based on the assumption that knowledge about the specific natural, cultural, economic and historical context within distinct regions is a prerequisite for regional development and innovation. In the 2000s, the regional institutions, both research institutes and university colleges, regained some momentum as central actors in what has been labelled the new regional paradigm (see Table 1.1). Whereas the old paradigm of regional policy centred on decision making by the central government, the new paradigm recognised regional specificities and complexities which called for a need to design and shape regional policies at the regional level. This has involved a place-based policy with focus on mixed, integrated and bottom-up approaches (Vanthillo & Verhetsel 2012). This implies that regional development and innovation warrant close collaboration between regional stakeholders and regional research institutes. In this respect the regional institutes may play the role as “brokers” between research and private/public sector, or they may operate as partners in common projects. In both cases they contribute due to their knowledge about the region and as an important part of the knowledge infrastructure in the specific region. Later in this chapter we introduce the term participatory research, where knowledge about both the regional partners, and the region as such, are important ingredients.

Table 1.1 Old and new paradigms of regional policy

Source: OECD 2010.

The establishment of regional research funds in 2010, as well as the Programme for Regional R&D and Innovation (VRI-programme) launched in 2007, have been important instruments in carrying out this regional policy in Norway. These tools were introduced to support and increase research efforts and subsequently encourage innovation, knowledge development and value creation within the regions. Regional research funds were established to support regionally prioritised efforts and strategies. However, they were also expected to enhance competence and develop relevant and competitive research communities in all regions. In spite of this regional policy, as much as 50% of the total public and private research and development (R&D) activity in Norway remains concentrated in the capital region of Oslo and Akershus.

In the 2000s, regional research institutes became increasingly affected by changes in regulations governing public tenders. The background for these regulations was a desire to improve public use of resources, secure equal treatment of market-based actors and to strengthen competition in these markets (NOU 2012, p. 2). For the regional research institutes, one implication has been increased competition from consulting firms offering evaluations, analyses and smaller studies for public principles. During the same period the competition to obtain financing from RCN has increased substantially, and now attracts an increased number of national and regional competitors. The basic grant to the research institutes is based on, among other things, the number of scientifically merited publications and the size of the academic staff. Due to demanding financial conditions in regional institutes, many researchers work with shorter assignments with little room for prioritising scientific publication, and hence most regional research institutes score lower than the national institutes on peer-reviewed publications. In smaller institutions, academic staff also often lack sufficient academic merit to pursue research activities of high quality resulting in scientific publications. This can be defined as a catch-22 situation.

Recently, there has been a debate regarding the optimal size of research institutes in Norway.2 There seems to be a consensus that larger research communities, which are more oriented towards scientific publications of high quality, are the way forward. To secure sustainable institutions, the lower limit for receiving a basic grant from RCN is defined to be 20 full-time equivalent researchers. On average, the regional institutes receive 12% of their income through the basic grant and other grants from RCN, with an additional 23% coming from competition-based research projects from RCN (contributory funding). In comparison, the total share for national institutes from RCN is 10 percentage points higher, including a higher basic grant.

From this, we argue that regional research institutes now need to adapt to a situation with increased competition in all markets; not only against national and international research institutes with better and more secure financial terms, but also with consulting firms and universities in need of external funding. At the same time, most of the regional institutes continue to define themselves as regional, with a clearly stated goal of contributing to various regional development processes, as originally intended. In practice, the most successful regional institutes have taken on roles as national institutes, maintaining a high academic level which makes them competitive in national and international research arenas.

Many regional institutes maintain that they have an improved relationship with the private sector, which is not affected by the strict regulations governing the system of public tenders. This relationship was reinforced by the establishment of the triple helix concept of research-industry-government relationships initiated in the late 1990s (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff 1997). Triple helix became an influential policy concept that emphasised the potential for innovation and economic development by the hybridisation of elements from the three mentioned arenas (also exemplified in the VRI-programme (presented in Chapters 2, 3 and 12 in this book). As a result, some regional institutes have more emphasis on commercial innovation and development, and less research devoted to social and political development in the public sector. This kind of specialisation may be a good way to compensate for size, but many institutes have not managed to develop research communities of sufficient scientific merit to be competitive in national and international research arenas. One important question is how the original regional policy of supplying academic and research competence in a broad sense to the regions may be maintained in the future.

Applied regional research institutes, such as Agder Research, must successfully address a complex and often competing set of role expectations in order to secure a sustainable financial and professional business development. In this chapter we identify a typology with three roles for applied research; contributory, commissioned and participatory. These three roles represent different sets of stakeholders, normative expectation, competitors and collaborators, as well as demands on researcher training and expertise. Further complexity is added by increased national standardisation and regulation of the institute sector in addition to the specific characteristics of the set-up of the R&D sector in the Agder region and beyond. Shifts in the competitive situation imply that new business models must be developed in order to secure a sustainable practice for applied research. Based on this our main question is: how can one develop a sustainable business model for an applied research institute, balancing the different and often conflicting institutional rationalities, demands and expectations?

We present and analyse data from RCN describing the structure and dynamics of the Norwegian institute sector. The data identifies some factors that seem to support both academic and financial development in the research institutes, and based on an understanding of these dynamics we discuss the previous research question.

The Norwegian institute sector

The research institutes in the Norwegian institute sector were established at different times, with different stakeholders, user groups and policy areas in mind. The gradual and organic growth of the sector has led to considerable variations in size, type of institutes and academic specialisation. This heterogeneity, in combination with a clear thematic and user-oriented specialisation, is characteristic of the institute sector in Norway. A common feature is that the institutes conduct R&D on a “not for profit” basis and that the organisations do not fit directly under an educational institution (e.g. a university). From this, the research institutes serve markets and develop knowledge for use in the private and public sector. The institutes are consequently inter-disciplinary and market-oriented, and most importantly, participants conduct applied research in Norway.

Structure

RCN is responsible for managing the Norwegian research institute sector. In 2014, they made a revision of the requirements for institutes to receive basic funding: