![]()

Chapter 1

Clumsy Floodplains

The Social Construction of Floodplains

Although more and more money is invested in flood protection (Loucks et al. 2008: 541, Strobl and Zunic 2006: 383), almost every year, extreme river floods cause enormous and increasing damage in floodplains (Munich Re Group 2003a: 14, Strobl and Zunic 2006: 411). The probability of extreme flood events increases as well in the future due to climate change (IPCC 2007: 8, UBA 2003: 1); in addition, our cities become more vulnerable (Cooley 2006, Fleischhauer 2004: 30–31). Usually water managers face this situation by building high and strong levees alongside the rivers. Such constructions, however, reduce the capacity of rivers to cope with the enormous water masses. Still, urban development takes place in these floodplains (e.g. Loucks et al. 2008: 541, UBA 2003: 148). Therefore, floodplains are contested land: places of extreme floods and places for urban development. The European Commission stated in 1999 that human activity supports these developments by:

straightening of rivers, settlement of natural floodplains and land uses which accelerate water runoff in the rivers catchment areas (ESDP 1999: article 319).

Heinz Patt (2001: 12), however, emphasises that even without anthropogenic activity extreme floods can occur almost everywhere and that the less a flood is expected, the more it severe will be. Nonetheless, in the past and still today, urban development takes place in riparian landscapes and levees are necessary to protect the immobile values in the floodplains (Strobl and Zunic 2006: 391). As a consequence, space for the rivers is shrinking. Levees take space from the rivers. Along the River Elbe, for instance, 2,300,000,000 m3 of retention volume has been lost since the twelfth century due to levees. This is a reduction of 86.4 per cent of the original retention area from 6.172 km2 to 838 km2 (Engel et al. 2002: 3). This caused an increase of the flood levels up to 50 cm in Wittenberge (IKSE 2003: 24). Levees were heightened and strengthened. Eighty-five per cent of alluvial plains along the River Rhine diminished due to river constructions (City of Cologne 1996: 1–6). Similar developments happened at almost all big rivers in Germany. This lost retention volume is needed today to reduce flood risk in order to reduce flood damages (Strobl and Zunic 2006: 389). Space for the rivers is needed. Also internationally, ‘land management is regarded as the most effective mitigation measures available’ (Cooley 2006: 111). But giving space for the rivers is complex.

How should we use floodplains wisely in the future? In the aftermath of the 2002 flood in the Czech Republic and Germany, claims for withdrawing from urban land uses in the floodplains along the River Elbe emerged; but due to time, people lost sight of and forgot about the floods. Little by little, urban use in floodplains intensified again (Bahlburg 2005: 12). This pattern of human activity is characteristically in the floodplains: technical river constructions – especially strong and high levees – lead to a high discharge capacity of rivers; smaller flood events drain off without damage, which provokes additional urban developments in floodplains (Kron 2004: 9–12, Patt 2001: 2). In this manner, the contest between humans and the water continues: floodplains are contested land.

Floodplains are defined as potentially submergible riparian land. They encompass land between levees or embankments of a river as well as flat areas behind the levees, which could be inundated by an extreme flood or crevasse of levees. This understanding of floodplains encompasses the two categories of submergible land according to the German Federal Water Act (Wasserhaushaltsgesetz, WHG): Überschwemmungsgebiete (§ 76 WHG, formerly § 31b WHG) and überschwemmungsgefährdete Gebiete (§ 31c WHG 2005). Überschwemmungsgebiete are not sufficient for this research, because areas, which might be inundated by extreme floods or through crevasses are not covered by the definition in § 76 WHG respectively § 31b WHG 2005. Überschwemmungsgefährdete Gebiete according to § 31c WHG 2005 include such areas as well (whereas this category has been abandoned during the reform of water law in 2010). How is this potentially submergible land managed in the face of the contest between humans and the water?

Iteratively, humans behave in the same patterns of activity in floodplains. Most of the time, landowners are using floodplains profitably. They build houses, enjoy the riverside and just live close to the waterfront (Strobl and Zunic 2006: 391). When floods threaten their houses, water management provides sandbags and private relievers help to protect the houses. Then, water management agencies, supported by policymakers, build and improve levees in order to defend against floods. In consequence, planners perceive floodplains as secure and grant additional building permits to landowners, which accumulate additional value behind the levees. Barrie Needham describes the general pursuit for building in the Netherlands: ‘A nation that lives, builds for its future’ (2007a: 25). This is also the mood sustained by the German planning and property regime. So, floodplains are under pressure of urban development.

Levees ought to protect the immobile values in the floodplains. But levees protect only against smaller floods, up to thresholds. Extreme floods threaten the houses, economic enterprises, infrastructure and facilities in floodplains even behind levees. Additionally, levees capture the river and accelerate the discharge, which leads to higher water levels. Finally, flood risk increases, more flood damages result. The risk increase through levees and value accumulation behind the levees is more or less obviously observable along every river in Middle Europe. The risk increase results from prevalent patterns of human activity. It is in this manner not an environmental constraint but a social construction. At least in Germany, these clumsy patterns of human activity are apparent, as I will describe in the following section.

Patterns of Human Activity

A water manager at the flood protection agency of Saxony-Anhalt, concluded after the 2002 flood:

Bewusstseinsmäβig ist Einiges falsch gelaufen 2002. Einige haben sich einfach saniert. Die haben teilweise ein neues Haus bekommen. Die wollten zwar alle direkt danach wegziehen, aber jetzt ist alles neu und schön, die haben einen Deich undfühlen sich sicher. Wenn ein Schaden eintritt, dann sind wir verantwortlich. [According to risk mentality, things went wrong in 2002. Homeowners wanted to move away after the flood, but then most of them renewed their homes; some even got a new house. Now everything is new and nice, they feel safe behind the improved levees. When a new flood event occurs, we, the water management agencies, are responsible.] (Water manager in Saxony-Anhalt in an interview in 2008)

These patterns of human activity persist and yield increasing flood risk: in the future all rivers will be captured by strong and high levees and intensively urbanised floodplains (IKSE 2003: 3). Although policymakers provide a lot of money for flood protection and set up directives to make space for the rivers (this policy was first set up in the Netherlands in the 1990s) (Greiving 2006: 73), municipal planning agencies grant building permissions in floodplains.

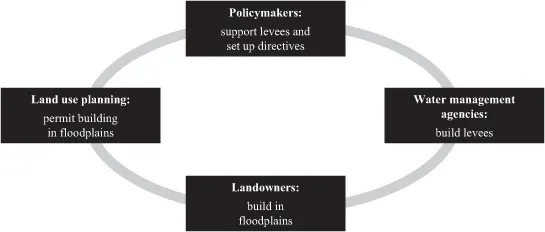

Figure 1.1 Patterns of human activity

Also in other European countries, planners struggle with providing space for the rivers, as Karen Potter concludes about the British system:

The practice of floodplain restoration remains in its infancy and is not keeping apace with the policy rhetoric. (Potter 2008: 345)

Even extreme floods do not prevent landowners from building close to the rivers. Landowners and land use planners rely on levees and think levees can provide security against flooding. Finally, four stakeholders are essential for the described clumsy patterns of human activity in floodplains (see Figure 1.1): policymakers, land use planners, landowners, and water management agencies.

The activities of these four stakeholders correspond to and depend on each other, depicted in Figure 1.1 with the grey line. The diagram can be read counterclockwise as the following: landowners are not allowed to build in floodplains without building permission by the land use planners. Since landowners accumulate immobile values in floodplains, water managers must build levees. Values behind levees justify levees, but levees can only be realised if policymakers provide money for this purpose. Local planners can only permit building in floodplains as long as policy gives them some scope for local planning decisions. These social relations between the four essential stakeholders persist. It hinders concepts like space for the rivers.

Die Rheinpfalz, a German regional newspaper, wrote in July 2007:

Der Hochwasserschutz ist ins Wasser gefallen – An der Elbe sind fünf Jahre nach der Jahrhundertflut Deiche erhôht – Forderungen nach mehr Raum für den Fluβ bleiben unerfüllt. [Five years after the 2002 flood, the claim for more space for the rivers is not implemented, but levees have been heightened] (Die Rheinpfalz, 29 June 2007).

The policy for space for the rivers fails in Germany. Following the reasoning above, space for the rivers is not only a technological task, but also a social task. Since some years, water professionals explain their problems and solutions to other stakeholders and start to regard water management not simply as a matter of technical concerns (Lane 2006: xiii-xiv). Indeed, floodplain management is a misnomer. It is not the floodplain, but the people that must be managed (Bollens et al. 1988: 311). But the four stakeholders are entrenched in their patterns of activity. Why do stakeholders not change the situation and reduce risk by providing space for the rivers?

Timothy Moss and Jochen Monstadt (2008) explain the diffident mobilisation of space for the rivers with the high complexity of such projects. Policymakers have to cope with this complexity. Recent scientific publications often identify complexity as a problem of inter-institutional coordination, in particular between regional planning, municipal planning and sectoral planning (Düsterdiek 2001: 1201–2, Haupter and Heiland 2002, Stüer 2004: 416, UBA 2003: 149). Many authors emphasise regional planning as most important for coping with this complexity, and explain how regional planning should coordinate all relevant issues of flood protection in a catchment (Greiving 2003, Haupter et al. 2007: 518, Moss and Monstadt 2008, Seher 2004). Others claim for informal institutions (Zehetmair et al. 2008), or want the European Union to govern flood risk management (Arellano et al. 2007: 466–7).

In sum, these approaches are based on ‘a widespread belief’, consisting of ‘three mental shortcuts’: first, it is assumed that environmental management is a problem of coordination; second, consultation solves lacks of coordination; third, ‘consultation is inseparable from consensus’ (Billé 2008: 77).

The consensual search for coordination via consultation underestimates the real antagonisms that exist between ‘uncoordinated’ stakeholders and uses, the differences of interests and of representations (Billé 2008: 78).

This antagonism has to be described to analyse the complexity of floodplains management. It cannot be explained with surveying facts, weighing up probable costs and benefits of various possible interventions, and moving from there to the right answer (Ellis and Thompson 1997: 208). Rational choice theory, where people act rationally in order to maximise their utility (Cooter and Ulen 2004: 15), cannot explain the whole story of the floodplains. We continue to observe the opposite of ‘wise’ and ‘rational’ floodplain management (Loucks et al. 2008: 541).

Cultural Theorists support the position that such a ‘Newtonian policymaking’ approach is appropriate for noncomplex systems; but it fails in complex systems (Ellis and Thompson 1997: 208). Social systems, however, are rather complex like ecosystems (Ellis and Thompson 1997: 209). In such social systems, cost-benefit analyses, probabilistic risk assessment and general equilibrium modelling will not be useful tools in designing and redesigning institutions. Moreover, the contending social framework of problem and solution between different audiences must be identified (Ellis and Thompson 1997: 209). Like in coastal zone management, Raphael Billé writes, floodplain management is not managed by a manager, but it is rather ‘a process without a pilot’ (Billé 2008: 79). So, many different stakeholders contribute to the social construction of floodplains. This frames floodplains as complex social systems. Identifying the social system requires an analysis of the contending perceptions of different stakeholders in floodplains.

Perceiving Floodplains

If you jump into the water, you will get wet. Regarding floodplains as social systems does not neglect this fact. Floodplains are certain pieces of riparian land. You can measure their size, determine the soil conditions, or identify land uses by remote sensing. Following these statements, there is nothing social about floodplains. Really? What are typical attributes that an inhabitant of the floodplain would assign to these landscapes? How would water management engineers declare floodplains? Insurance officers, planners, politicians, foreigners, tourists, disaster management workers, farmers, captains … different social actors assign different attributes to floodplains – depending on their ‘condom of monorationality’ (Davy 2008: 304). What are these condoms? These condoms represent their rationalities. They are like filters in people’s heads, which protect them from being raped by the plural rationalities (Davy 2008, based on Simmel 1903). For example, as a tourist, it would not be suitable to regard floodplains through the eyes of a farmer. For the one, floodplains serve as places for recreation, for the other the same place is a working place. The condoms – the rationalities – protect individuals from being overwhelmed by the different rationalities. Floodplains are socially constructed through different rationalities – through different perceptions and filters for reality. This does not necessarily mean that everything that happens in floodplains can exhaustively be explained by social constructions:

Rather, ideas of nature are plastic; they can be squeezed into different configurations but, at the same time, there are some limits (Thompson et al. 1990: 25).

Rationalities influence patterns of human activity. Indeed, rationalities are often not apparent; rather they are hidden as different cultures, ways of life, biases and perceptions (Thompson et al. 1990). To uncover the rationalities, which underlie the social construction of floodplains and frame the activities of the stakeholders, the four most important stakeholders have been interviewed. The discussions with policymakers (officers at ministries and regional planners), local land use planners (and mayors), water managers and randomly selected landowners in flood-prone areas in Cologne-Rodenkirchen, Biederitz near Magdeburg, Dessau-Waldersee, Bitterfeld and Torgau uncovered different perceptions of floodplains in different phases. The qualitative empirical research was conducted in semi-structured narrative interviews of approximately 15 to 40 minutes. The aim was to learn more about the perceptions of the stakeholders. The following four perceptions have been identified out of the interviews, observation, analysis of literature and other documentation according to flood events (e.g. newspaper, DVDs, publications, radio and TV reports): floodplains are profitable, floodplains are dangerous, floodplains are controllable, and floodplains are quite as inconspicuous as any other terrain. These four perceptions of floodplains differ essentially.

Profitable floodplains Floodplains attract a number of land uses. Large settlements are likely located along rivers (Cooley 2006: 91, Petrow et al. 2006: 717). Since the beginning of the explosive growth of populations in the nineteenth century, and due to the industrial revolution, floodplains became more and more attractive and increased in value; engineers and planners protected these areas with levees (Strobl and Zunic 2006: 384). New developments took place in flood-prone areas (Bahlburg 2005: 12, Greiving 2006: 73). Why do people live in floodplains? Landowners reacted to this question in an astonished way: ‘Warum wir hier leben? Schauen Sie sich doch mal um! Es ist herrlich hier!’ [Why we are living here? Look at the beautiful landscape! It is great here!], or: ‘ich kann von meiner Terrasse aus den Rhein sehen’ [I can see the River Rhine from my terrace].

Indeed, the reasons for settling in floodplains vary, but often the beautiful nature and the scenic landscape were emphasised. For most people interviewed, flooding was no topic for their individual allocation decision. Often landowners were not aware of the possibility of flooding when they bought or built their homes on floodplains. Some were warned by experienced neighbours (e.g. in Biederitz near Magdeburg), nevertheless people moved into the riparian landscapes. Municipalities rarely inform landowners about the risk of flooding. The interviewed landowners confirmed that only few moved away after a flood, and most would even stay after further extreme floods: ‘Hier ist unser Geld, hier ist unsere Anlage’ [Here is our money, here is our investment]. People still demand riparian building sites; building in floodplains is a profitable business (Bollens et al. 1988: 312).

Floodplains provide fertile farmland, recourses, for economic development and drinking water, and they act as corridors for transport (Petrow et al. 2006: 717).

High quality residential, commercial and industrial areas have been developed in the past and will still be developed in the future. Planners, investors, architects, engineers, building companies – a whole industry thrives from building in floodplains. Interviews with land use planners confirmed that spatial planning supports this industry by granting building permits, mayors are lobbying building in floodplains. At the local level, economic interests for building in floodplains often drowns obligations of water managers (Bahlburg 2005: 12). In particular, local enterprises located in flood-prone areas need additional land in floodplains for extensions of existing facilities with the argument of workplaces (Greiving 2006: 73). Since local economies often rely on such enterprises, it is likely that municipalities will fulfil their demands.

Landowners feel relatively safe behind high and strong levees. The majority of landowners affirmed that they could cope with further floods: clean up the mess, rebuild and stay. A usual response was that people who live in areas at risk have to arrange themselves with the threat. In conclusion, landowners who already live in floodplains stay and bear the risk, because they want to enjoy their property and rate this as an important value.

According to new developments in floodplains, interviewed water managers complained about municipal planners: they would often not believe in statistical risk calculations. They do not want to hear about restrictions, but rather opportunities for urban development. At the municipal level, flood risk maps are threats for new urban developments. Water managers explained that land use planners at the municipal level justify urban developments in floodplains with personal experience of a few years when no flood occurred. Regional planners affirm these statements: if no flood occurred for some years, municipal planners perceive floodplains as attractive land for building. Restrictions from water management or regional planners are not welcome at this time. Regional planning is almost unable to restrain building in floodplains, as it came out in the empirical study. Indeed, questioned local land use planners emphasised that building in the floodplain is essential for the economic and social future of municipalities. Especially for bigger towns it would be necessary to provide attractive building sites for young families, because those towns need inhabitants and they have to restrict u...