eBook - ePub

Discourse Dynamics in Participatory Planning

Opening the Bureaucracy to Strangers

- 218 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book introduces the methodology of critical discourse analysis (CDA) to the study of participatory planning. CDA uses linguistic analysis to elucidate social issues and processes and is particularly suited to institutional practices and how they are changing in response to changing social conditions. Illustrated by two case studies from Australia, it examines the talk between the various participants in a formal stakeholder committee context over five years, during which time they went through several phases of changing power dynamics, conflict and reconciliation. The book demonstrates the value of CDA to this field of research and develops specific techniques and conceptual tools for applying the methodology to the 'formal talk' context of collaborative planning committees. It also sheds light on the dynamics of interaction between 'stakeholders' and bureaucracies - particularly with respect to inherent communicative barriers, power inequalities, and the development of new discursive practices.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Discourse Dynamics in Participatory Planning by Diana MacCallum in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Local & Regional Planning Public Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Age of Participation

1.1 A brief personal account

You can have the choice, you can go back to the confrontationism of the past which have [sic] wrought such havoc and damage to the Australian political fabric, or you can have the approach which is based upon an attempt not to force some ideology down the throats of the people of Australia, but to recognise that the concepts of planning together and working together, the harnessing of shared experiences, that that is an alternative, and a better way.

(Prime Minister Robert Hawke, Speech to Brisbane Press Club, 9 August 1983)

In the early 1980s, ‘consensus’ was adopted as a central policy aim of Australia’s Federal Labor government.1 Process-oriented approaches to policy development, emphasising communication and consultation with interest groups, became mainstream and widely expected.

It was shortly after this that I began my professional life. For several years from 1986, I worked for various locally managed organisations considered to represent one or another special interest in land.2 I was occasionally invited by government agencies to participate in land use decisions either as a ‘stakeholder’ (defined as someone affected by the decision) or as an advocate for a ‘disadvantaged’ interest group. This turned out to be a rather disheartening experience for me and my colleagues. Bureaucrats often appeared to be ‘going through the consultative motions’, rather than genuinely interested in what we had to say. At other times – and especially when I was in the advocate role – they seemed sincere but clueless when it came to obtaining meaningful input from community members. For our part, we never doubted for a moment that meaningful consultation was important.

In the mid-1990s I took a job in the state public service. Suddenly, consultation no longer seemed so straightforward. The people in my office wanted it to work, and used many of the standard methods – consultative committees, public meetings, written invitations to comment, public notices, and surveys. But the number of stakeholders involved and their often irreconcilable differences meant that it was scarcely feasible to communicate with all the main players, let alone to please everyone. Even of those stakeholders we managed to identify, some consistently failed to turn up for meetings and many tended to be defensive or hostile when we did get to see them. Further, the only practical way of achieving ‘consensus’ often seemed to be to remove all contentious content from policy documents and produce what are popularly known as ‘motherhood statements’ – ‘meaningful’ consultation seemed to lead to meaningless outcomes.

While the above representation is overstated, the point is that my experience of the consultation process was bound to the particular role I played in it, apparently more than to either the methods used or to any imagined ‘independent’ subjectivity. This seemed to suggest that misunderstandings might be somehow intrinsic to the relationship between public servants and stakeholders, presenting a potentially formidable barrier to community participation. Even without significant disagreement on the issues, communication is likely to be problematic if participants give entirely different meanings to their interaction.

In strategic participatory planning processes, as opposed to merely consultative ones (see for example Bishop and Davis 2002; IAP2 2007), participants are engaged in a rather special type of interaction with the bureaucracy. This is not the ‘coalface’, where citizens directly affected by bureaucratic decisions regarding their property, for example, communicate with decision makers about their personal issue(s) and experience. Rather, it is where such issues and experience are generalised and repackaged in quasi-impersonal – that is, bureaucratic – terms: those involved are becoming one with the planning institution, not simply talking to it. Whether or not they share a frame of reference with that institution, therefore, may have profound consequences.

This book grew from such reflections. The enquiry that it presents aims to account for the type of ‘systematically distorted communication’ (Habermas 1970) that I had found so frustrating, by examining participatory planning not as simply the reconciliation of substantive values (cf. Susskind et al. 1999), but as an encounter between bureaucratic and other types of practices. The key question motivating the enquiry is: how might tensions in participatory planning be resolved?

This question, as I argue throughout this book, is not simply a procedural one about methods for dispute resolution or dialogue, but a cultural one, about situated social action. Taken from such a perspective, my motivating question raises a number of conceptual issues:

• the ‘culture’ (or cultures) of planning itself;

• the nature of the ‘tensions’ that subtle cultural difference can create;

• the meaning of ‘resolution’ in the cultural realm;

• the likelihood that cultural difference can never, and perhaps should never, be finally ‘resolved’: how, then, should the ‘resolution’ of cultural tensions be understood and valued, particularly in conditions of unequal power?

• the impact of these dynamics on the (substantive and institutional) outcomes of participatory processes.

These issues are not easy ones to address. They concern the talk that takes place between citizens and with government officers – how it gets into trouble, how these troubles are resolved – and therefore require analysis of that talk. Thus, they demand attention, over significant periods of ‘real’ time, to the fine detail of specific communications, rather than to either retrospective accounts or generic communicative/procedural norms. Such detail is rarely available to research: time, practicalities, confidentiality frameworks, and a range of sensitivities tend to work against it. Moreover, methods for the systematic interrogation of fine detail are not well developed within the planning and policy disciplines (Allmendinger 2002a). Hence, in spite of considerable scholarly attention to participation, and especially to developing normative frameworks for its administration, the question of what actually happens when people from different realms come together to make decisions has been relatively neglected.

The enquiry presented in this book tackles both the problems noted above. First, it explores the above issues through two longitudinal ethnographic case studies, each of which represents a fairly typical response to the demands of participation: the establishment of a community-based committee to make decisions about a project on behalf of a public agency. The interactions of committee members – realised as discourse – instantiate and help to shed light on not only the dynamics of ‘tension’ and ‘resolution’, but also the relationship between these processes and their changing political, social, spatial and temporal contexts. Second, the enquiry extends the methodology of critical discourse analysis (CDA) – in which micro-level textual analysis is put to work to elucidate social processes – to the study of participatory planning. To date, text analysis in this tradition has tended to focus on relatively static texts (in particular written/printed and graphic materials), providing little insight into the more ephemeral communications – especially talk – that make up much of participatory practice (but see Weiss and Wodak 2003; Hausendorf and Bora 2006 for counterexamples). Therefore, this book develops tools to deal with this increasingly common but still slightly mysterious communicative space.

The use of two cases allows some comparisons with respect to a number of contextual differences: state/local authority, multiple/single stakeholder group(s), environmental/urban planning, scientific/humanist orientation, and outcomes/process focus. The point is not to generalise from the experience of the committees with respect to these ‘variables’, but rather to explore how identifiable consequences of these differences provide insight into the dynamics and limitations of participatory planning (Flyvbjerg 2001). That is, the case studies illustrate some of the tensions posed by current transformations of public sector practice, and how these tensions are negotiated in specific situations.

1.2 Two stories of participatory planning

The case studies’ environment was regional (non-metropolitan) Australia at a time of booming economic conditions driven especially by rapid growth in demand from South East Asia for natural resources. There was considerable pressure on the regions to prepare themselves to host significant new investments in industrial and tourism development, which meant among other things to have land/water available and growth management strategies in place. These matters were often highly contentious, leading to ongoing conflict both between citizens and government and between localities and central administrations.3 In this context, public and stakeholder participation in settling such matters was high on the political agenda. Policies were developed to this end and in some cases special offices established to promote ‘best practice’, based on international experience and literature, across government.

These pressures – both the drive to attract foreign direct investment and the imperative to incorporate and manage public/stakeholder opinion – reflected worldwide trends. While the Australian institutional/constitutional framework is unique, the practices of public servants in this broader political-economic context drew on discourses, ideas and methods which are circulating internationally, particularly in the USA, UK, Canada and Europe. As such, the issues, problems, behaviours and strategies that characterised these case studies will be familiar to planners, policy analysts and public administrators throughout the world.

One of the most common mechanisms adopted for stakeholder participation is what the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2 2006; 2007) calls the ‘Advisory Committee/Group’, which is seen as going beyond mere consultation (‘give us your opinion and we’ll consider it’) by involving non-government actors in the ongoing business of decision making. Both the case studies are instances of this technique, advisory committees which represent attempts by the respective authorities to involve a group of major stakeholders in developing a plan in the face of hitherto intractable land/water use conflicts. They thus instantiate at least a nominal commitment to participation and cooperation between government and other sectors, and exemplify the problem that generates my motivating question. However, this commitment was implemented in very different ways in the two cases, as the following brief de-identified stories suggest.4

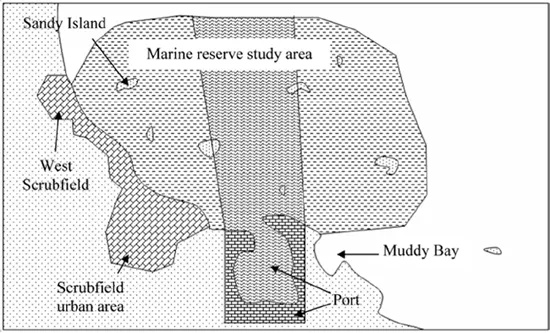

Figure 1.1 Scrubfield Marine Reserve study area

Scrubfield Marine Reserve Committee (SMRC)

Throughout the 1990s, in a town called ‘Scrubfield’, there was intense conflict over natural resources in the adjacent coastal waters. The catalyst for much of this conflict was growth in local commercial fishing and aquaculture industries, which was seen by many as likely, first, to restrict access to certain areas for recreational fishing and, second, to intensify pressure on the area’s stocks of table fish. This led to several outbreaks of direct action5 on the part of recreational anglers following the announcement of new, proposed or renewed commercial licences. Thus, the most visible conflict was between recreational and commercial exploiters of marine biological resources. However, the area was also used for shipping and other rapidly growing industrial activities, including infrastructure development associated with oil exploration, which were increasingly seen as a threat to the environmental and aesthetic qualities of the area, and there was growing public debate surrounding these issues as well. And added to all of these issues and stakes were Indigenous ownership and cultural heritage claims, whose compatibility with different uses and perspectives was as yet unnegotiated and uncertain.

In the early 2000s, the state government nominated the waters off Scrubfield (Figure 1.1) as a marine reserve, partly to bring order to the political chaos noted above but also, more importantly, as part of a program to establish a national system of marine protected areas, one of several strategies being undertaken Australia-wide to meet international biodiversity agreements. Scrubfield was chosen – according to a government report – for both ecological significance and increasing human impact. Responsibility for progressing the nomination rested with the ‘Department of Marine Management’ (‘DOMM’), who would develop a draft management plan as a first step to making it happen. DOMM had a strong scientific management tradition, but its policy had recently been changed to require full consultation with the community before management plans could be adopted. However, there were few associated changes to DOMM’s statutory mandate, or to the practices through which they actually managed (as opposed to planned) reserves. Therefore, the requirements for the management plan’s content (as staff understood them) remained relatively static.

The focus for the consultation effort in Scrubfield was a committee – the ‘Scrubfield Marine Reserve Committee (SMRC)’ – with membership from a range of commercial, industrial, recreational, scientific and cultural stakeholders, and with decision-making authority over the content and text of a draft plan (which would then be subject to Ministerial approval). In executing this authority, SMRC’s members were expected to take into account inputs from other stakeholders and community members, gathered through a broad consultation program which ran alongside the committee meetings.

SMRC met nine times over two and a half years (2000–03) before approving a draft plan to be put out for public consultation. The process that they took to achieve this was a linear one, in which sections of the plan were written mostly in the order of DOMM’s proposed table of contents (see MacCallum 2008). For ‘wordy’ parts of the plan, DOMM assisted by drafting text for consideration; this was often amended by the committee, but many members complained that these meetings were rather uninspiring (see MacCallum 2002; 2005). Most attention was given, later, to producing a zoning plan for the proposed marine reserve, for which SMRC began with a ‘blank sheet’, a great deal of habitat and usage information (mapped on a Geographic Information System [GIS]), and strong personal opinions. All committee decisions were reported after each meeting in letters to a range of stakeholders with invitation to comment, a technique which elicited very little response. The zoning plan, however, was the subject of a much more intensive consultation effort, including also staffed displays at shopping centres, staff briefings to various local clubs, and three public meetings organised by a local recreational anglers’ lobby group, whose president was an SMRC member. The zoning generated a relatively high level of interest; the committee amended its original plan three times in response to comments they received.

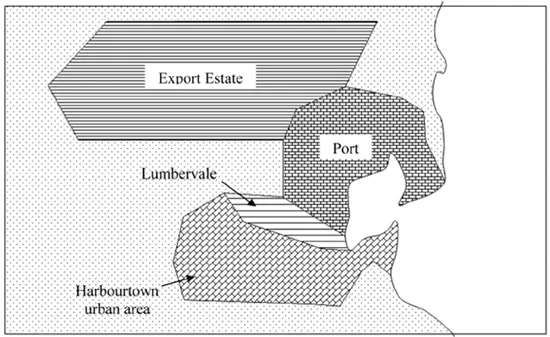

Figure 1.2 Harbourtown

In spite of this apparently fairly comprehensive effort, SMRC’s draft plan was not, in the end, accepted by all its members, a small number of whom lobbied government for major changes after the committee’s final planning meeting, delaying for almost two years the plan’s release for public comment. The released plan was significantly different from the one proposed by the committee, and when they finally met for the last time to consider the public submissions, in early 2006, most members strongly objected both to the changes and to the time that the process had taken. As at the end of 2009, the marine reserve has still not been declared.

Harbourtown Industry Commi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Age of Participation

- 2 Participatory Planning: A Cross-cultural Meta-practice?

- 3 Science and Politics: DOMM and SMRC

- 4 Practice and Practicality: SOHE and HIC

- 5 Deliberative Ideals: SMRC’s Decision Making

- 6 Strange Practices: HIC’s Decision Making

- 7 Opening the Bureaucracy

- Bibliography

- Index