- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fiduciary Duty and the Atmospheric Trust

About this book

This book explores the application of concepts of fiduciary duty or public trust in responding to the policy and governance challenges posed by policy problems that extend over multiple terms of government or even, as in the case of climate change, human generations. The volume brings together a range of perspectives including leading international thinkers on questions of fiduciary duty and public trust, Australia's most prominent judicial advocate for the application of fiduciary duty, top law scholars from several major universities, expert commentary from an influential climate policy think-tank and the views of long-serving highly respected past and present parliamentarians. The book presents a detailed examination of the nature and extent of fiduciary duty, looking at the example of Australia and having regard to developments in comparable jurisdictions. It identifies principles that could improve the accountability of political actors for their responses to major problems that may extend over multiple electoral cycles.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fiduciary Duty and the Atmospheric Trust by Charles Sampford,Ken Coghill,Tim Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Law Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Rulers’ Duties to Our Environment?

Long-term policy issues and administration affecting the public interest raise major concerns about how democracy can achieve its ultimate purpose of ensuring ‘responsive rule’, that is, the ‘necessary correspondence between acts of governance and the equally-weighted felt interests of citizens with respect to those acts’.1 Citizens are the best judges of their felt interests, and elections involving universal and equal suffrage are the quintessential means for reflecting them. However, such elections are necessarily crude and blunt instruments of accountability because of their infrequency and the fact that so many overlapping and partially conflicting interests, policies and values have to be reduced to a single decision on which candidate or party to vote for.

While citizens should be able to recognize their longer-term interests in the kind of future they and their children will enjoy, the usual media and electoral political cycles militate against their consideration. Elections cannot make our political institutions responsive to the interests of others who are affected by political and commercial decisions taken today – including future generations, non-citizens, residents of other nations and other species. How can these longer-term interests (and values) of citizens and the interests of various classes of non-voters be taken into account? One possibility may be found in the principles of public trust and fiduciary duty founded in Equity.2 Such principles seem to offer a basis for arguing that government ministers have a duty to discharge a public trust in respect of the climate.

The implications for accountability of the executive government are considerable. A higher standard of accountability would apply. The executive would be held accountable for the discharge of a public trust over and above simply acting lawfully, ethically and in response to elections.

Here we examine the implications for government in the particular case of climate change. However, note that these implications may not be limited to the political executive. A further question arises as to whether fiduciary duty and/or public trust can be invoked to argue for ordinary members of parliament having a general responsibility to act in a longer-term ‘public interest’ that is not founded on electoral mandates in the particular case of climate change. Again, fiduciary duty may offer a basis for arguing that MPs have a duty to discharge a public trust in respect of the climate.

If this argument led to a view that members of parliament have a general responsibility to act in this longer-term public interest in the particular case of climate change, there are implications for how parliament would address the issue. For example, parliamentary committee processes similar to scrutiny of legislation might take a greater role than politically charged contests on the ‘floor of parliament’.3

These issues are highly relevant to concerns of citizens over failures by governments to support effective action on what may be the greatest threat to ever face human civilizations. They may suggest that those governments, like earlier rulers before them, have a fiduciary duty to their long-term interests and the interest of non-voters. They may also suggest that the voters themselves – the ultimate rulers in a democracy – also have such fiduciary duties.

In this work these concerns are addressed by a diverse range of authors, who examine whether the ancient concepts of fiduciary duty and public trust can be revived, re-interpreted and invoked to stimulate governments to more effective action to protect citizens’ common interest in the atmosphere that they share with each other and with non-voters. They consider how governments could be held accountable where they neglect to act effectively,4 asking if accountability can be advanced by invoking the concept of fiduciary duty and/or public trust. Could either or both have particular application to responsibility for policy responses to climate change and/or to accountability for the discharge of those policy responses?

The dawning awareness of the concerning state of the atmosphere has crept up on governments somewhat slowly until they suddenly face Apocalypse Now!5 For more than an entire generation people have seen the evidence slowly emerging that mankind is polluting, depleting and destroying the very environment on which all civilizations depend. To adapt the words of scientist and author Tim Flannery in The Future Eaters,6 the knowledge that mankind is eating its future has been increasingly well known for decades.

Elements of this knowledge were well established in specialist scientific circles long before it entered the popular media with the publication of The Limits to Growth in 1972.7 At that time, any crisis for mankind seemed decades away, but nonetheless actions were begun by some governments. President Jimmy Carter, a trained scientist, came to the White House and, in a highly symbolic measure, had solar hot water units installed on the roof in 1979.8

The evidence base expanded and links between the environment’s sub-systems became better understood. In 1985, British Antarctic Survey scientists reported alarming rapid thinning of the ozone layer, especially over higher southern latitudes. In summers, it was developing a huge hole extending as far north as southern Australia, exposing people to dangerous levels of ultra-violet radiation.9 Such dramatic changes egged governments on to action. In this case, the available solution was relatively simple, low cost and did not disturb citizen’s life-styles. Within only two and half years, governments had agreed to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer at a meeting in Montreal on 16 September 1987.10 Within a very few years, the effectiveness of the Protocol would become apparent.

As data mounted confirming risks to climate due to excessive discharges of greenhouse gases (GHG), principally carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from combustion of oil and coal, Governments appeared to demonstrate concern for the interests of people they served. In 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), held in Rio de Janiero and commonly known as the Rio Earth Summit, concluded with what seemed major steps forward. The steps included the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which was signed by heads of government including then US President George Bush (Senior).11 It was ratified by the US Senate later that year. Governments began introducing domestic policies to limit CO2 emissions.

President Bill Clinton and Vice-President Al Gore came to office in 1993. Gore was especially committed to effective action. Clinton’s Administration led negotiations which agreed on the ‘Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’ (Kyoto Protocol).12 However, the composition and orientation of the US Senate had changed markedly and it was now strongly opposed to Clinton’s initiative, so much so that the Protocol was not presented for ratification (though he did sign it in the dying days of his presidency as a symbolic gesture). His successor, President George W. Bush, who came to office in 2000, repudiated US support for the Protocol.13

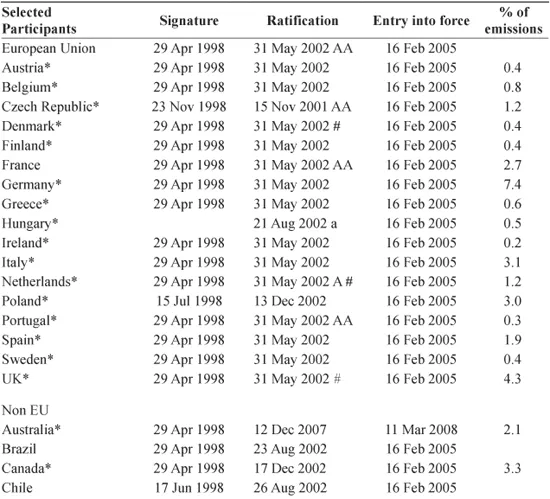

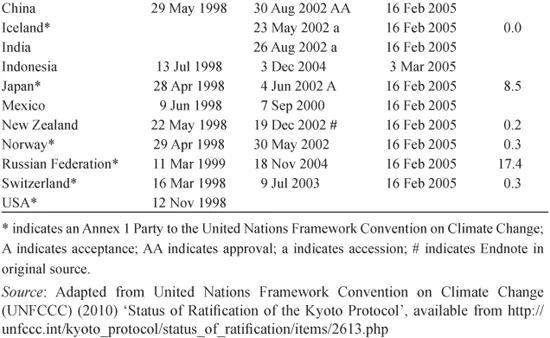

Nonetheless, many countries ratified the Protocol (see Table 1.1) and a number, including the European Union (EU), made policy changes and implemented measures to put it into effect. The EU established a ‘cap and trade’ emissions trading scheme (ETS) as provided for in the Protocol.

Despite the readiness to sign, ratify and bring into effect the Protocol by almost all other developed countries responsible for significant CO2 emissions, the government of two of the worst per-capita offenders, USA and Australia, refused to act. In the case of the USA that opposition was a product of the President’s policy position, although it is improbable that the Senate would have ratified it if asked.

In Australia, the Howard Government – a coalition of the conservative Liberal Party and the rural-based Nationals (the ‘Coalition’) – refused to move in advance of the country’s strong ally, the USA. Howard appeared to deny the scientific evidence and justified his action on economic grounds.14 The issue emerged as a major concern of the Australian public and was a major point of difference between the Coalition and the Australian Labor Party (ALP) at the 2007 national elections. The Coalition had made belated gestures towards an ETS, such as announcing legislation, but it lacked credibility on the issue. The ALP campaigned strongly on the issue and won what seemed to be a strong mandate15 to implement effective action to curb CO2 emissions – action which most of the ALP and the commentariat thought involved an ETS.

Table 1.1 Selected signatories to Kyoto Protocol

Ratification of the Kyoto Protocol was one of the very first actions by the incoming ALP Government and the Protocol came into effect in early 2008. A bill for an ETS, the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme Bill (CPRS) was introduced. However, it attracted strong criticism from deniers and major business interests on the right of the ideological spectrum and from environmentalists concerned that it was weak and would be ineffective. A minority were concerned that carbon trading schemes were inefficient, inequitable and fatally flawed. The Opposition (Coalition), especially the Liberals, was deeply divided. The ALP Government appeared to play on the divisions amongst the Opposition and made little attempt to explain, defend or promote its climate change policies.

The Government aimed for passage of the CPRS shortly before the 2009 UNFCCC COP15 conference in Copenhagen (COP15). The conference had been planned to reach global agreement on extension of the Kyoto Protocol beyond the initial commitment period.16

This, then, was the political context within which the authors met for the workshop that led to this book. The disappointing response to such a fundamental issue facing policy-makers raised accountability for inadequate policy responses as an increasing concern for scholars and others. The Accountability Round Table (ART), already active on various matters affecting the accountability of the political executive17 shared this concern and was aware of the interesting potential of the fiduciary duty of the political executive as argued by Finn18 and later work in Canada and Europe by Fox-Decent19 and by Wood20 in the USA. ART worked with GovNet (the Australian Research Council’s Governance Research Network) to organize the workshop to bring together some of the finest minds to explore that potential. The workshop drew together Australian, Canadian and United States expertise from academia, the judiciary and politics with the objective to ‘explore and develop potent...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Notes on Contributors and Editors

- 1 Rulers’ Duties to Our Environment?

- 2 Fiduciary Duty and Climate Governance: Challenges for International Diplomacy and Law

- 3 Public Trusts and Fiduciary Relations

- 4 Trust, Governance and the Good Life

- 5 Public Officials, Public Trusts and Fiduciary Duties

- 6 Atmospheric Trust Litigation Across the World

- 7 Fiduciary Principles and International Organizations

- 8 High Court of Australia on Fiduciary Theory

- 9 Applying Fiduciary Duty in Real Politik

- 10 Fiduciary Duty, Democracy and the Rule of Law

- 11 The Role of Fiduciary Duty in Safeguarding the Future

- 12 A Ponzi Scheme on the Environment? Failures of Fiduciary Duty and the Challenges of Climate Governance

- 13 From Fiduciary States to Joint Trusteeship of the Atmosphere: The Right to a Healthy Environment through a Fiduciary Prism

- 14 Conclusion

- Index