eBook - ePub

Russian Energy in a Changing World

What is the Outlook for the Hydrocarbons Superpower?

- 218 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Russian Energy in a Changing World

What is the Outlook for the Hydrocarbons Superpower?

About this book

For a long time Russia's position as a key global energy player has enhanced Moscow's international economic and political influence whilst causing concern amongst other states fearful of becoming too dependent on Russia as an energy supplier. The Global Financial Crisis shook this established image of Russia as an indispensable energy superpower, immune to negative external influences and revealed the full extent of Russia's dependence on oil and gas for economic and political influence. This led to calls from within the country for a new approach where energy resources were no longer regarded wholly as an asset, but also a potential curse resulting in an over reliance on one sector thwarting modernization of the economy and the country as a whole. In this fascinating and timely volume leading Russian and Western scholars examine various aspects of Russian energy policy and the opportunities and constraints that influence the choices made by the country's energy decision makers. Contributors focus on Russia's energy relations with the rest of the world alongside internal debates about the need for diversification and modernisation in a changing economy, country and world system where overdependence on energy commodities has become a key concern for customer and supplier alike.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Russian Energy in a Changing World by Jakub M. Godzimirski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Political Economy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Actors, Ideas and Actions

Jakub M. Godzimirski

Introduction

This chapter presents the key actors, ideas and actions shaping the Russian energy sector in recent years. The analysis focuses on three closely intertwined aspects: the actors who shape Russian energy policy, their ideas and world outlook, and the most important actions they have undertaken in the post-crisis period (2008–2012). Which actors have been central to the processes of formulating and implementing of energy policy in Russia after the crisis? Has the crisis led them to reformulate their policies and goals? Since Tatiana Mitrova’s chapter in this book examines how the crisis has affected the formulation of goals in Russian energy policy, this chapter focuses on the actors, their ideas and their political actions.

We begin with a look at the key figures, followed by a brief analysis of their ideas on the role of the energy sector in Russia. The third part looks at their main actions that have shaped this important sector of the Russian economy.

Actors

There are at least three possible approaches to identifying the key actors in the Russian energy sector. The first is to consult the lists of owners and managers of major energy companies to see who is in charge of development.1 That would rapidly reveal that the state is an important owner, controlling approximately 80 per cent of gas production, between 30 and 40 per cent of oil production, and with an effective monopoly on transport and export of those two major energy commodities.

This clearly dominant role of the Russian state in the energy sector may make the second approach to identifying key actors more viable. That approach would use the various Russian rankings of political, reputational and economic power published regularly in the media – such as the rankings of the country’s top 100 politicians published by Nezavisimaya Gazeta – to identify key actors in the energy sector.

The third way would be to analyse the composition of the state bodies responsible for the development of the energy sector. Which energy actors have a seat in those official bodies and thereby a direct say in shaping energy policy in Russia?

Here, however, it should be borne in mind that the Russian political system is characterized by several specific features. The energy sector has been defined as ‘strategically important’– and strategic decisions require not only economic justification on the company level, but also political approval at the highest level. For that reason, we will combine the three approaches. Only by comparing and merging various ‘name lists’ can we see whose influence has a visible impact on the development of Russia’s energy sector.

This analysis is based on a top–down approach. The truly strategic decisions are probably taken informally at the highest political level and then ‘pushed down’ the power vertical. That does not mean that those decisions will always be implemented smoothly, as various groups of interests or individual actors may block their realization. A clear illustration here could be the fate of the strategic deal on cooperation and assets swap made between Rosneft and BP in January 2011 that was directly supported by Vladimir Putin and Igor Sechin: it was effectively ‘killed’ – at least temporarily – by a group of powerful Russian oligarchs led by Mikhail Fridman.

This painful reputational defeat notwithstanding, the ‘Putin team’ still seems to be very much in charge. Even though their party of power, United Russia, failed to cross the 50 per cent threshold in elections to the new State Duma on 4 December 2011, and a wave of protests swept the major cities, the opposition was apparently too weak to pose any real threat to the ruling group.

This impression was also confirmed by the annual ranking of political power published by Nezavisimaya Gazeta on 16 January 2012 (Orlov, 2012), and then by the results of presidential elections won by Vladimir Putin. Summing up the results of the year 2011, Orlov wrote that Putin had preserved and even strengthened his position; that leaders working closely with Putin had improved their positions; and that the members of the current elite had consolidated their grip on power. The federal administrative elite dominated the ranking, followed by members of the party elite, the regional elite and the business elite. Almost 60 per cent belonged to the first group, 20 to the second, with the regional and business elite represented by 10 per cent each.

The same five names occupied the top five places in 2011 and in 2010, but with some important changes. In 2010 the Putin–Medvedev tandem had been followed by Aleksander Kudrin (Minister of Finance), Vladislav Surkov and Igor Sechin. In 2011 the same tandem was followed by Surkov, Sechin and Kudrin, in that order. In 2012 a clear regrouping on the top of the Russian power pyramid took place – Putin and Medvedev retained their top positions, but they were followed by I. Shuvalov, V. Volodin and S. Ivanov. Igor Sechin was demoted to the sixth place, Surkov – to the eight place, while Kudrin ended up at 77th place.2

This demotion notwithstanding, Aleksander Kudrin has indeed played a crucial role in shaping the framework conditions for the energy sector since 1996, when he joined the Presidential Administration as its deputy head, working closely with Anatolii Chubais. It was Kudrin who proposed that Putin be appointed as deputy head of Yeltsin’s presidential administration, when he himself left the administration to work as Russia’s representative in the International Monetary Fund in May 1997. In the same year Kudrin was appointed state secretary in the Russian Ministry of Finance. After a brief break between January and June 1999 he was reappointed as first vice-minister of finance and in May 2000 was appointed Minister of Finance of the Russian Federation. He served continuously in that capacity until September 2011, when he was forced to resign. During his time at the top of Russian politics he played a crucial part when decisions were made on increasing the fiscal burden for Russian energy producers by reintroducing (in 1999) export duties and linking the level of taxation to global energy prices, thereby securing additional revenues for the state budget. Further, the introduction of the severance tax, known in Russia as the Mineral Extraction Tax (NDPI) in 2002, replacing a more complex earlier tax system, was to provide the state with additional mining rent (Goldsworthy and Zakharova, 2010). This focus on the fiscal aspects of energy policy also resulted in the budget proposal made in 2006, where Kudrin proposed the establishment of the Russian Stabilization Fund, which helped the country to cope with the financial crisis and made the state budget better prepared to cope with the volatility of oil prices by providing a financial cushion.3

However, Kudrin’s power position was drastically weakened by his row with Medvedev, which finally resulted in his dismissal from the Russian government in late September 2011. While in August 2011 Kudrin had occupied the third position in the Top 100 ranking, already by October, only a few weeks after his argument with Medvedev, he had been demoted to 47–49 position,4 and by November 2011 his name was in 77th place on the list.5 He managed a slight recovery in December 2011 (returning to 44th position) – due mainly not to his own achievements but to the fact that Putin had mentioned publically that Kudrin was still to be treated as a member of his team.6 In the meantime, Anton Siluanov, Kudrin’s former deputy who was appointed Minister of Finance after Kudrin’s forced departure, not only made the list in November 2011 when he was ranked 93, but soared to 28–29th position by December 2011 and was expected to enter the top ten in the first months of 2012.

In the same period, Igor Sechin, who was formally responsible in the Putin government for the political management of the country’s energy sector, climbed from fifth position in August 2011 to third position in December 2011, overtaking not only Kudrin, who had fallen from grace, but also Vladislav Surkov, the influential deputy head of the Presidential Administration and a man seen as the main ideologue of the Kremlin. Sechin’s formal appointment as Deputy Prime Minister responsible, inter alia, for the development of nation’s energy sector,7 his friendship with Vladimir Putin dating back to the early 1990s and his ability to play a major part in the current political game made him one of the three most influential players in Russian politics (Sakwa, 2011; Reznik and Mokrousova, 2011). According to some observers, he was at some stages even more influential then President Dmitrii Medvedev8 (see also Pribylovskiy, 2010: 5–6). In any case, there can be no doubt that Sechin’s formal and informal power has been much greater than that of any other energy player in Russia.

From the 2011 list of Russia’s most powerful figures it was clear that many of them played a role or had a stake in the energy sector, whether as state managers and state representatives (Miller, ranked as no. 17; Zubkov, 29; Tokarev, 59; Kiriyenko, 72), as owners (Alekperov, 25; Usmanov, 34; Fridman, 57; Yevtushenkov, 69; Aven, 95), as traders (Timchenko, 35), or as policymakers (Kudrin, 5; Shuvalov, 10; Trutnev, 66; Shmatko, 85).

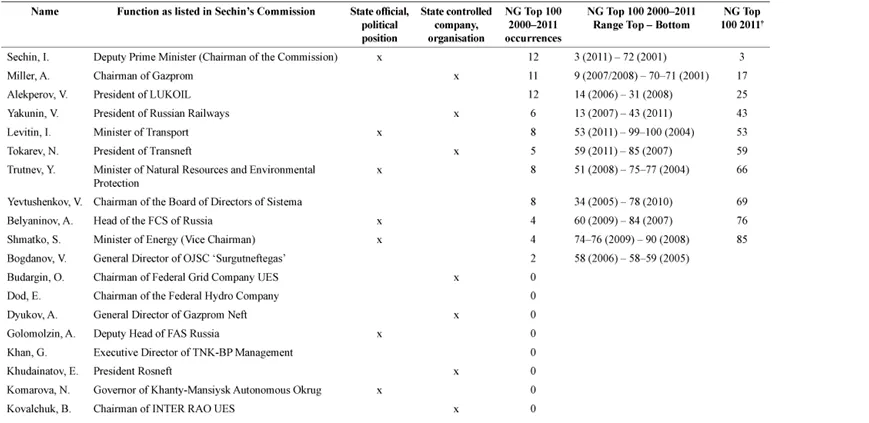

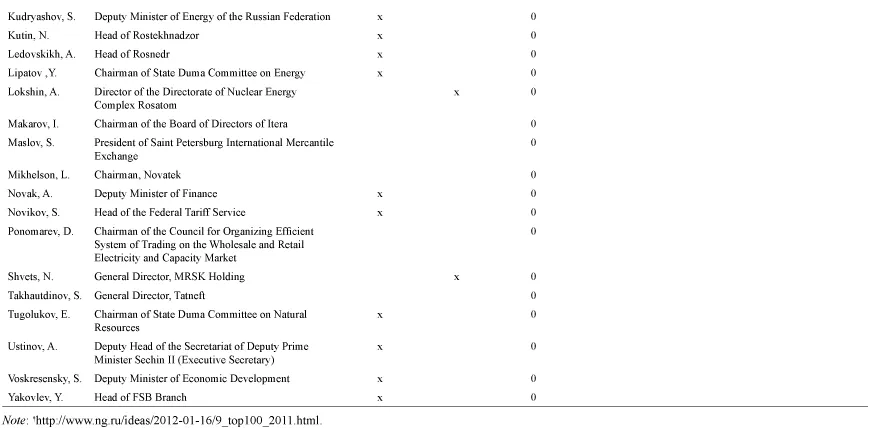

Many of them have also sat on the Governmental Commission on Fuel and the Energy Complex, the Mineral Resource Base and the Energy Efficiency of the Economy under Deputy Prime Minister Igor Sechin.9 The main tasks of the Commission were to coordinate cooperation among federal executive bodies, executive bodies of subjects of the Russian Federation and other organizations, to work for sustainable development and operation of the country’s fuel and energy complex, and to ensure the development and implementation of state energy policy. The list of members and their institutional and business affiliations can therefore serve as a useful guide showing who the key players in the energy sector were during Medvedev’s presidency and while Sechin was formally responsible for shaping Russia’s energy policy. The Commission had grown from 32 members in 2010 to 36 by 2011. Fourteen of these members represented various state institutions, two represented the legislature, one represented regional elite, and the remaining 19 came from the business community.

Although the business community may appear well represented, we should recall that the Russian state is a key owner in many companies represented in the Commission: in Rosneft (via Rosneftegaz) in 2011 the state owned 75.16 per cent; in Gazprom Neft (via Gazprom) 95.7 per cent; in Gazprom 50.002 per cent; in Transneft 78.1 per cent (the state’s share of votes here is 100 per cent); in Holding MRSK 53 per cent; in the Federal National Electric Grid 79.11 per cent; and in the Russian Railroads 100 per cent. In addition, Rosatom is organized as a state corporation. The composition of this important Commission thus confirms the dominant position of the Russian state in the energy sector.

Table 1.1 combines data from the 12 annual Top 100 rankings published by Nezavisimaya Gazeta (NG) between 2001 and 2012 with an overview of affiliations of members of the Sechin Commission. The names are presented with those with greatest political influence in 2011 at the top and those with less political clout at the bottom. This should offer a good indication of the most influential energy actors as of the end of 2011, and in which institutional environment they operated, representing the interests of key energy companies and of various state institutions with direct or indirect stakes in the Russian energy sector.

Several members of the Commission deserve further mention. Among them is Boris Kovalchuk. Although he does not feature in any of the NG Top 100 rankings in the period studied here (2001–2012), he has a strong family connection to the Russian power elite – his father, Yuriy Kovalchuk, co-owner and manager of the Rossiya Bank, is a close associate of Vladimir Putin, with whom he became acquainted in St Petersburg in 1991. His close association with Putin made him an important political figure in Putin’s Russia, and his name featured in all NG Top 100 rankings since 2007, with best position achieved in 2008 (ranked as 27–28) and the lowest in 2011 (88).

Anton Ustinov, who is thought to be a relative of Vladimir Ustinov, a close ally of Sechin (Sakwa, 2010, p. 188), served as the head the legal department of the Federal Tax Service. In February 2008, Kudrin fired him from that post, but in May 2008 he was appointed aide to Deputy Prime Minister Igor Sechin. According to the Russian media, Ustinov has played a key role in many of the most notorious tax cases in the country, including the Yukos case (Vedomosti, 2008; Ukhov, 2008).

Eduard Khudainatov is another interesting case. He had a seat on the Commission as the CEO of the state-owned oil and gas company Rosneft. In 2010 he replaced Sergei Bogdanchikov, who was believed to be Sechin’s man and who managed to use his position to gain political clout. Bogdanchikov had been ranked among the most influential figures in Russia in the years between 2004 and 2010, climbing to 28th position in 2006, then falling to 87th position in 2010 and disappearing from the list in 2011 after he had lost his post in Rosneft.

A member of the Commission with apparently increasing political clout is Leonid Mikhelson, CEO and main owner of Novatek, the biggest of the ‘independent gas producers’ in the country and close associate of another important Russian/Finnish energy player, Gennadii Timchenko, who is also one of Novatek’s main shareholders. In early 2012, it was even rumoured that Mikhelson might replace Alexei Miller as the CEO of Gazprom.10 In that case, Mikhelson would probably join the group of the most influential energy policy makers in Russia. Regardless, he is still among the major energy players in the country,11 and the one who managed to break the Gazprom export monopoly effectively, by signing the deal with Total on production and export of LNG from Yamal.12

Table 1.1 Members of the Sechin TEK Commission, ranked by their position in the Nezavisimaya Gazeta top 100 ranking 2011

It has not been possible to amend this table for suitable viewing on this device. Please see the following URL for a larger version http://www.ashgate.com/pdf/ebooks/9781409470304Tab1_1.pdf

Although the Commission was made up of the key players in Russian energy sector, it was wid...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: Understanding Russian Energy after the Crisis

- 1 Actors, Ideas and Actions

- 2 Oil Industry Structure and Developments in the Resource Base: Increasing Contradictions?

- 3 After the Crisis: New Market Conditions?

- 4 The Modernization Debate and Energy: Is Russia an ‘Energy Superpower’?

- 5 ‘Resource Curse’ and Foreign Policy: Explaining Russia’s Approach towards the EU

- 6 Diversification, Russian-style: Searching for Security of Demand and Transit

- 7 The Impact of Domestic Gas Price Reform on Russian Gas Exports

- 8 The Future of Russian Gas Production: Some Scenarios

- 9 Russian Energy: Summing up and Looking Ahead

- Index