eBook - ePub

The Hidden Order of Corruption

An Institutional Approach

- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

When corruption is exposed, unknown aspects are revealed which allow us to better understand its structures and informal norms. This book investigates the hidden order of corruption, looking at the invisible codes and mechanisms that govern and stabilize the links between corrupters and corruptees. Concentrating mainly on democratic regimes, this book uses a wide range of documentation, including media and judicial sources from Italy and other countries, to locate the internal equilibria and dynamics of corruption in a broad and comparative perspective. It also analyses the Transparency International Annual Reports and the daily survey of international news to present evidence on specific cases of corruption within an institutional theory framework.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Hidden Order of Corruption by Donatella della Porta,Alberto Vannucci in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politik & Internationale Beziehungen & Rechtstheorie & -praxis. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Hidden Order of Corruption: An Introduction

Karachi, May 8, 2002. A few minutes past 8 a.m.: a car parked on Club Road, between the two largest hotels in Pakistan’s capital, explodes, leaving 14 victims, 11 of which were French engineers and technicians working for the DCN (Direction des constructions navales), under the direct control of the French Ministry of Defense. The suicide bomber activated the explosive as their bus passed in front of the parked car. With the memory of September 11 still fresh, the investigations targeted the Al-Qaeda network. President Chirac solemnly proclaimed the French government’s intention to fight against terrorism, confirming their cooperation with the Pakistani government: the same government that, in the previous 10 years, had bought arms from French firms for a total of €2.1 billion, 3.5 percent of French exports. Arms deliveries were, however, at the center of several corrupt exchanges, including the payment by French enterprises of large bribes to various Pakistani military and political exponents, among them the brother of general Musharraf, who became Prime Minister after the coup d’etat of 1999. Various military leaders were also sentenced for having received US$7 million in bribes for the construction of Agosta 90B submarines (Le Figaro, June 25, 2009). Five months after the bombing, the DCN manager Philippe Japiot wrote, in a letter to a French judge investigating the case, “it is because of the submarine contracts that our French colleagues died” (Libération, June 25, 2009). Not Al-Qaeda, but the interruption in the payment of bribes to military and political leaders was, in this interpretation, behind the terrorist attack (Libération, July 10, 2009). According to the lawyer for the relatives of seven victims of the attack, “It is all linked to Jacques Chirac’s refusal, in 1996, to pay the commissions linked to the selling of the submarines.” The attack aimed to convince the French partners to continue to pay the expected bribes.1

The Karachi tragedy presents various obscure aspects, which the French judges continue to investigate. In the latest, and most reliable, narrative, however, there are several aspects that are relevant for our perspective on corruption. The reality of corruption, in fact, can take very different forms, including a small exchange involving only two actors, in which a tiny kickback is secretively handed to a public administrator in exchange for a modest favor, such as forgetting a fine or speeding up the procedures for delivering a certificate. But, as in the previous example, corruption can also stratify, involving several actors in the most relevant positions in complex relations, and the change of hands of large sums of money.

A double source of uncertainty derives from the illegal nature of (small and large) corrupt exchanges. First, there is the obvious risk of being discovered, denounced, and punished by the investigating authority, and of being stigmatized by various agencies of social control. Second, there is the risk of being cheated by the partners, who may renege on their promises and fail to pay bribes or provide the agreed favors. In the latter case, the partners cannot of course ask a judge to protect their rights regarding exchanged resources. Other instruments of protection then become necessary—as in the extreme case reported above, this may even include terrorist violence. Other forms of retribution are possible, however, depending on the contacts and resources available to the actors involved. As scholars, we can also note that when these tensions explode, this often reveals hidden aspects that allow us to better understand (and tackle) corruption.2

Endogenous weakness notwithstanding, corruption succeeds, in some societies, to take root in all the parts of the public administration, in political processes, and in market relationships. In these societies, the expectation of bribes orients public expenditures as well as other public decisions, and the redistribution and reinvestment of illegal profits define political and economic careers. The do ut des of corruption becomes the inexorable norm for all those who enter into relations with the state or other contractual partners. The world of corruption is therefore far away from the anomic reality of the Hobbesian state of nature, in which reciprocal mistrust and a lack of predictability make relations precarious and dangerous. On the contrary, a vast range of regulatory mechanisms and governing structures for corrupt exchange are voluntarily created or spontaneously emerge. Through these informal institutional constraints and resources, the actors involved in corruption can reduce uncertainties and the risk of defections or denunciations and increase hopes of impunity as well as their illicit profits.

In this research, we investigate this hidden order of corruption, looking at the codes and mechanisms that govern and stabilize the links between corrupters and corruptees and that increase the resources (of authority, economic, information, relations, etc.) at their disposal, strengthening the “obscure side of power.” Corruption renders public power more unaccountable and invisible, since accountability “depends precisely on the greater or lesser extent to which the actions of the supreme power are offered to the public, are visible, knowable, accessible, and therefore controllable” (Bobbio 1980: 186). This is why corruption is particularly dangerous for the quality of democracy, its consolidation and survival. In this research we therefore concentrate mainly (although not exclusively) on corruption in democratic regimes.

The main aim of this volume is to contribute to our understanding of the ways in which networks of corrupt exchanges develop because of their hidden order, that is, through an internal governance that encourages actors to accept the risk of illegal deals, trust each other, and build and enforce invisible codes, norms, and reciprocity rules. In this sense, our analysis is inspired by an institutional approach in so far as we look at the roots of those informal institutions that allow corrupt deals to expand and flourish within certain decision-making processes. Rather than trying to explain the evidence of corruption generally or in specific cases, we use empirical materials on corrupt exchanges in Italy and in other countries with the purpose of illustrating the main actors and mechanisms that play a role in the formation, enlarging, consolidation, and (sometimes) crisis of the hidden order of corruption. Although this book does not focus on anticorruption policies, in the final chapter we reflect on the potential relevance of our analysis for practices aimed at corruption control.

What Is Corruption?

In the social sciences, in parallel with the growing interest in the topic of corruption, there has been an animated debate on the very definition of the phenomenon. True, there is a broad consensus conceptualizing (political and bureaucratic) corruption as an abuse by a public agent: “corruption is commonly defined as the misuse of public power for private benefits” (Lambsdorff 2007: 16). However, the problem of singling out the standards against which this violation can be assessed remains open to discussion: formal norms, public interests, and public opinion standards being among these standards. Moreover, the abuse of entrusted power for private gain can assume different forms and contents. Besides corruption in a stricter sense, embezzlement, favoritism, nepotism, clientelism, vote-buying, fraud, extortion, or maladministration are often used as synonymous or corresponding terms to describe corrupt relationships involving public administrators.3

In our perspective, however, there is a risk of concept-stretching in the adoption of a similar “almost all-encompassing” definition of corruption.4 To avoid (or at least reduce) this, we believe it better to differentiate the basic constitutive components of corruption by adopting a principal-agent scheme.5 There are different kinds of illicit, dysfunctional, or malfunctioning operations within the political and administrative realm, and corruption is but one of them. As Bryce (1921: 477–8) observes, “‘Corruption’ may be taken to include those modes of employing money to attain private ends by political means which are criminal or at least illegal, because they induce persons charged with a public duty to transgress that duty and misuse the functions assigned to them.”

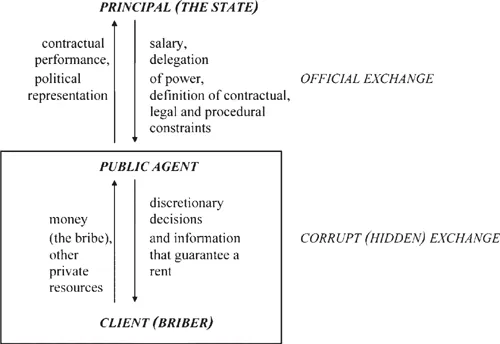

The so called principal-agent approach offers a clear way to conceptualize the logic of corruption. In formal terms, corruption (see also Figure 1.1) is defined as:

(i) the illegal and therefore hidden violation of an explicit or implicit contract

(ii) that states a delegation of responsibility from a principal to an agent who has the legal authority, as well as the official and informal obligation, to use his discretionary power, capacity, and information to pursue the principal’s interests;

(iii) the violation occurs when the agent exchanges these resources in a (corrupt) transaction

(iv) with a client (the briber), for which the agent receives as a reward a quantity of money—the bribe—or other valuable resources.

(ii) that states a delegation of responsibility from a principal to an agent who has the legal authority, as well as the official and informal obligation, to use his discretionary power, capacity, and information to pursue the principal’s interests;

(iii) the violation occurs when the agent exchanges these resources in a (corrupt) transaction

(iv) with a client (the briber), for which the agent receives as a reward a quantity of money—the bribe—or other valuable resources.

In political and bureaucratic corruption, moreover:

(va) the principal is the state (in a democracy, the citizens) while the corrupted actor is a public agent;

while in private corruption:

(vb) the principal is a private actor or organization, and the corrupted actor is a private agent.

Within any organization there are contractual relations—which can be expressed in more or less formal terms—between agents, delegated to make specific decisions, and the principal, who delegates to the corresponding power. The latter can be a collective actor: in liberal democracies, politicians and bureaucrats are agents to which the state—as a principal, that is, the sovereign people—delegates, through various mechanisms (electoral competition, public competition, lot, etc.) the task of pursuing the public interest in the formation and implementation of public policies. The complexity of the tasks delegated to agents makes a detailed list of clauses in the relations between the principal and the agent impossible. The distinction of roles and functions nevertheless responds to this fundamental distinction: public agents do not act on their own account, but are delegated to accomplish those tasks that are expressions of the interests of their collective principal, to whom the exercise of their power has to be—at least to a certain extent—accountable.

Fig. 1.1 Public corruption within a principal-agent model.

Any agent, however, is also a bearer of private interests that may not necessarily coincide with those of its collective principal, from which he can hide information on the characteristics and content of his activities. So, in delegating power and tasks to the agent, the principal lays down rules and procedures that limit his range of discretion, and develops various mechanisms of control and (legal, administrative, social, political) sanctions in case of the misuse of delegation, thereby reducing risks of conflicts of (private and public) interest. Among these rules is the prohibition against accepting illicit payments from other actors for the accomplishment of delegated tasks, as this would increase the risk of the agent disregarding the interest of the principal. Illegality is therefore an essential attribute of corruption. Legal norms, and specifically the norm prohibiting the agent from accepting “bribes” in the exercise of his public duties, define the constraints on the agent’s activities in accordance with the principal’s interests, as perceived and stated in that particular context. Moreover, the very illegality of corrupt activities increases their transaction costs and expected risks, therefore generating a demand for protection within that murky environment. This implies a substantial difference from the social mechanisms regulating contiguous but legal practices, such as clientelism, favoritism, and so on, which if exposed are eventually sanctioned only by social stigma.

We can speak of corruption when a third actor enters into, and distorts, the relations between agent and principal. The intervention of a client or a briber pushes the agent to sidestep the constraints and controls imposed by norms and procedures. The corrupter, by offering resources such as money or other utilities, succeeds in obtaining favorable decisions, reserved information, or the broader protection of his interests.

In its elementary logic, corruption is therefore a “three-player game,” in which an invisible and illegal exchange between an agent and a client/briber distorts the incentives to fulfill the terms of the contract with which the principal delegates responsibilities and discretionary power to the agent, in favor of the private interests of the agent and to the detriment of the interests of the principal.6 Even though corruption can also emerge in private relations, in this work, we focus on politico-bureaucratic corruption within the state, with a special focus on advanced democratic countries. The exercise of public power in a democratic government can be more realistically conceived as a complex chain of principalagent relationships between electorate, elected officials, and bureaucrats in their functional and hierarchical attribution of roles and functions. Moreover, the collective nature of the basic principal—that is, the sovereign people—makes it even more difficult to define univocally and to state contractually the principal’s interests and preferences, the realization of which is delegated to public agents. While bureaucrats are relatively limited in their activity by normative and procedural constraints, politicians can operate with greater discretion in pursuit of some presumed “true” general interests.

In the transaction between the corrupt agent and the client, property rights to rents created through the political process are exchanged. Corruption is “actually just a black market for the property rights over which politicians and bureaucrats have allocative power. Rather than assigning rights according to political power, rights are sold to the highest bidder” (Benson 1990: 159; Benson and Baden 1985). State activity, like market exchanges, modifies the existing structure of property rights. Public agents may use the coercive power of the state instead of voluntary transactions to allocate resources: the corrupters try to modify the structure of the property rights to their advantage with resources that are either public or subject to public regulation. A rent is created through (a) the acquisition of goods and services paid by the private actors for more than their market price, (b) the selling of the licensing of use of public goods for a lower price than their market price, or (c) arbitrary enforcement activities that selectively impose costs or reduce the value of some private goods to public agents (Rose-Ackerman 1978: 61–3).

By means of a hidden transaction, corrupter and corrupted share between them property rights to the political rent thus created.7 The corrupted official obtains a part of that rent in return for his services (decisions, confidential information, protection), which aim to guarantee, or at least increase the chances of, granting those property rights, usually in the form of a monetary bribe, but also in the form of other valuable resources (della Porta e Vannucci 1999a: 35–7).8

In this perspective, we can better distinguish corruption from other political misdeeds. Vote-buying, when illegal as in most states, is a subspecies of corruption in which the agent is the citizen in his public role as elector, selecting the people’s representatives, while the briber is the candidate—or the party—who purchases his vote in exchange for money or other valuable resources.9 Other activities, on the contrary, should not to be confused with corruption. In case of embezzlement, fraud, or conflicts of interest, for example, the agent also abuses the trust of principal; however, there is no third party involved. In extortion there is not an exchange of rents but rather the use of (physical or psychological) coercion to obtain resources for a private actor. In favoritism and nepotism, a “client” (who can be a relative) pushes the agent not to comply with his duties toward his principle, but the relationship is generally not overtly illegal—even when morally blameworthy and therefore not public—and, especially, no tangible resource is exchanged: deference, gratitude, and informal future obligations within familiar, political, or personal networks are at stake here. In clientelism, fin...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgments

- 1 The Hidden Order of Corruption: An Introduction

- 2 The Governance Structures of Corrupt Exchanges

- 3 Corruption as a Normative System

- 4 Bureaucratic Corruption

- 5 Political Actors in the Governance of Corrupt Exchanges

- 6 The Entrepreneurial Management of Corrupt Exchanges

- 7 Brokers in Corruption Networks: The Role of Middlemen

- 8 Organized Crime and Corruption: Mafias as Enforcers in the Market for Corrupt Exchange

- 9 Snowball Effects: How Corruption May Become Endemic

- 10 Conclusion: Anticorruption Policy and the Disarticulation of Governance Structures in Corrupt Exchanges

- Bibliography

- Index