eBook - ePub

The Neurobiology of Criminal Behavior

Gene-Brain-Culture Interaction

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The main feature of this work is that it explores criminal behavior from all aspects of Tinbergen's Four Questions. Rather than focusing on a single theoretical point of view, this book examines the neurobiology of crime from a biosocial perspective. It suggests that it is necessary to understand some genetics and neuroscience in order to appreciate and apply relevant concepts to criminological issues. Presenting up-to-date information on the circuitry of the brain, the authors explore and examine a variety of characteristics, traits and behavioral syndromes related to criminal behavior such as ADHD, intelligence, gender, the age-crime curve, schizophrenia, psychopathy, violence and substance abuse. This book brings together the sociological tradition with the latest knowledge the neurosciences have to offer and conveys biological information in an accessible and understanding way. It will be of interest to scholars in the field and to professional criminologists.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Neurobiology of Criminal Behavior by Anthony Walsh,Jonathan D. Bolen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Law Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The Basic Brain

The human brain—a walnut-shaped, grapefruit-sized, three-pound mass of gelatinous tissue—is the most immensely complicated, awe-inspiring and fascinating entity in the universe: “In the human head there are forces within forces within forces, as in no other cubic half-foot of the universe we know,” wrote Nobel Laureate neuroscientist Roger Sperry (in Fincher, 1982:23). The brain is the magnum opus of the millions of years of human evolution, and is the place where genetic dispositions and environmental experiences are integrated and become one as the brain physically captures them in its circuitry. Within this blob of jelly, which consumes 20% of the body’s energy while representing only 2% of body mass, lie our thoughts, memories, desires, emotions, intelligence, and creativity. Although we are a long way from fully understanding this “enchanted loom,” we cannot ignore what is known, in particular aspects of it relevant to criminology. Robinson (2004:72) goes as far as to say that any theory of behavior “is logically incomplete if it does not discuss the role of the brain.”

To travel the neurobiological road, criminologists need not be concerned with the minutia of brain anatomy and physiology any more than with the minutiae of mathematical derivations in statistics to conduct quantitative research. However, they should learn the basic language of neurobiology so that they understand the research it produces relevant to criminology, just as they learn the basic language of statistics to conduct research. We are not advancing a neurobiological-reductionist model of criminal behavior (“My neurons made me do it”), however. Neurobiological risk factors almost never represent a one-to-one causal relationship with behavior. Like any other risk factors, they are one aspect of a permutation and interaction of other risk and protective factors ranging from the molecular to the cultural. We intend to show that the brain is a marvelously plastic organ of adaptation that calibrates itself to environmental experiences. While this is a positive thing in general, it is also a negative thing for brains exposed to violent, abusive, and neglectful experiences and to noxious substances, as the brains of many seriously involved criminal offenders are. We intend to suggest how these negative exposures, in concert with congenital features of brain morphology and structure, diminish the control that affected individuals have over their behavior.

Holistic accounts of behavior cannot proceed with any kind of confidence without a solid foundation of fundamental knowledge, and that requires a large dose of reductionist science. Although holistic accounts are often more satisfying than reductionist ones because they supply meaning to our understanding of behavior, that meaning must rest on a solid foundation lest it collapse under the weight of error. Phenomena may find their significance in holistic regions, but they are explained by lower-level mechanisms. Science has made its greatest strides when it has picked apart wholes to examine the parts, and in doing so has gained a better understanding of the wholes they constitute. But we must never confuse the parts, however well understood, for the whole, and we must never overlook the parts in our haste to arrive at the whole. As Matt Ridley has opined: “Reductionism takes nothing from the whole; it adds new layers of wonder to the experience” (2003:163).1

Our approach conforms to Nobel Laureate Nikolas Tinbergen’s (1963) famous Four Questions. Tinbergen maintained that it is necessary to inquire about the following four questions in order to understand the behavior of any animal, including Homo sapiens:

1. Function: What is the adaptive function of this behavior—how does this behavior contribute to reproductive success?

2. Phylogeny: What is the evolutionary history of the behavior—how did it come to have its current form?

3. Development: How do genes and environments interact in individuals to develop variation in this behavior?

4. Causation: What are the causal mechanisms that trigger this behavior?

For example, consider a situation in which altruism is elicited. The Causation question asks what the immediate mechanisms underlying altruism are. Altruism is motivated by an empathetic understanding of why someone needs help, and empathy is underlain by brain chemistry. Performing the altruistic act facilitates the release of chemicals that target the reward areas of the brain, thus the helper is reinforced internally as well as externally by the enhancement of his or her reputation in the eyes of others as kind and dependable.

The Development question asks why altruism varies from one person to another. There are strong genetic influences on altruism and empathy, but all traits and behaviors are either nourished or starved by one’s developmental experiences across the life course.

The Phylogeny question asks how these traits/behaviors came to be in the course of evolution. Parental care and mother–child bonding surely serves as the template for later social bonding and for helping behavior that assists in forging those bonds.

The Function question asks what the adaptive features of helping behavior are—what are the fitness consequences of helping? Helping others ultimately helps oneself because it leads to reciprocal helping. Mutual help and support helps all those involved in a social group to avoid predators, to cooperate in hunting and gathering, and many other features of social life. Because these factors have obvious fitness consequences, there will be strong selection pressures involved.

No one carries out a research agenda animated by all of Tinbergen’s questions, but it is understood that all levels have to be mutually consistent. That is, no biologist would hypothesize a relationship between a hormone and a neurotransmitter that contradicts the known chemistry of those substances, just as no chemist would advance a hypothesis that contradicts the elegant laws of physics. Likewise, no hypothesis about behavior at a higher level of analysis should contradict what is understood at a more fundamental level—the level that enjoys the greater “hardness” (consensus, certainty) of its theories, methods, and data.

Basic Neuroanatomy and Physiology

The nervous system is divided into the central nervous system (CNS), composed of the brain and the spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system (PNS), which carries information to and from the CNS via the various sensory organs. The brain is endlessly fascinating and complex, and it is almost endlessly divisible. We will focus only on major areas that have been consistently implicated in all sorts of antisocial behavior. The brain is typically divided into four principal parts: the brain stem, diencephalon, cerebellum, and the cerebrum, but we favor the “triune” division into the reptilian, limbic, and neocortex system that reflects the brain’s evolutionary history.

The most primitive part of the human brain is the reptilian system, so called because it is just about all the brain a reptile has. It consists of the brain stem and the cerebellum. The system controls the survival reflexes such as breathing and heart rate, as well as movement, sleep, and consciousness. Part of the brain stem contains a finger-sized network of cells called the reticular activating system (RAS). The RAS regulates cortical arousal and various levels of consciousness that underlie sensitivity to the environment. Variation in RAS functioning leads to augmenting or reducing the incoming sensory information from the environment.

Wrapped around the reptilian system like a protective claw is a set of structures known as the limbic system. It is in the limbic system that we experience pleasure and pain, affection, anger, and joy. These are the basic emotions upon which the so-called social emotions (shame, guilt, embarrassment, and so forth) are retrofitted. Among the many structures of the limbic system are the amygdala, hippocampus, and anterior cingulate gyrus (ACG), each of which is distributed bilaterally. The amygdala’s primary function is the storage of memories associated with the full range of emotions, particularly fear. When the amygdala is aroused by a stimulus, it sends information to a part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex, which initiates a response geared to the stimulus. The hippocampus is specialized for storing and processing visual and spatial memories such as facts and events.2 Connections between the amygdala and hippocampus help to focus the brain on what the organism has learned about responding to the kinds of emotional stimuli that have aroused it in the past (“Do I run, fight, talk, ignore?”).

The curves of the cingulate gyri surround the wishbone-like structure of the limbic system and provide a connection between the limbic system and the cerebral cortex. The ACG has a number of functions, including mediating between conflicting response signals from the “rational” hippocampus and the “emotional” amygdala (Allman et al., 2001). It plays a role in self-control by helping the hippocampus to reign in negative emotions. People prone to aggression show attenuated activation of the ACG (Davidson, Putnam & Larson, 2000). The various parts of the ACG serve as processing stations for top-down and bottom-up stimuli arriving from various other areas, and assign appropriate control to them. According to Laurence Tancredi (2005:36), the ACG “provides for civilized discourse, conflict resolution, and fundamental human socialization.”

The limbic system is thought to have evolved in conjunction with the evolutionary switch from a reptilian to a mammalian lifestyle, which included the addition of nursing and parental care, and audiovocal communication. It used to be thought that limbic system emotional activity was an evolutionary “throwback” to more primitive times, and that because it was non-rational, it required cerebral inhibition (McDermott, 2004). The evidence today now points overwhelmingly to the position that the emotions perform many functions vital to social and cultural evolution (Nicholson, 2002; Phelps, 2006). Emotions do require rational guidance (but not inhibition), just as cognitions require emotional guidance. There is an intimate relationship between rationality and emotion, as the huge number of projections between the amygdalae and the hippocampi, as well as the apparent “refereeing” function of the ACG, attest (Richter-Levin, 2004). As a basis for social interaction, emotions clearly preceded rationality in evolutionary time, with rationality being added later to the more important role of social emotions such as love, empathy, shame, disgust, and embarrassment. Descartes’s famous apothegm “I think, therefore I am” would have been more accurately rendered as “I think and emote, therefore I am.”

Situated at the foremost part of the brain stem and linked to the limbic system is the thalamus. The thalamus is a dual-lobed structure that receives signals from the RAS and serves as a relay station for all kinds of sensory information except smell, and organizes and sends the incoming messages to the appropriate brain areas for processing. Just beneath the thalamus is the hypothalamus, one of the busiest parts of the brain. It is mainly concerned with maintaining homeostasis, the process of returning a biological mechanism to its normal set points after arousal. It also controls the endocrine glands via its control of the pituitary gland. Through its control of the pituitary and the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, it helps to regulate stress and emotional expression by balancing arousal and quiescence.

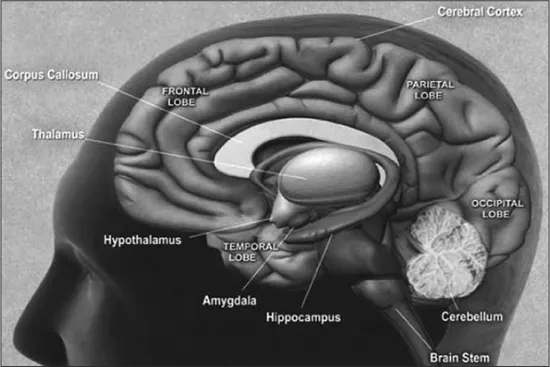

The most recent evolutionary addition to the brain is the cerebrum, which forms the bulk of the human brain. The cerebrum is divided into two complementary hemispheres with their own specialized functions, and is connected at the bottom by the corpus callosum. The right hemisphere is specialized for perception and the expression of emotion, and the left hemisphere is specialized for language and analytical thinking (Parsons & Osherson, 2001), although the two hemispheres work in unison like two lumberjacks at each end of a saw. The right hemisphere is more specialized in processing visuospatial patterns and is more holistic, in that it grasps the fragmentary abstractions processed by the left hemisphere in a more integrated way. Figure 1.1 illustrates some of these important brain structures.

Figure 1.1 Some important brain areas pertinent to criminal behavior

Source: <http://www.nia.nih.gov/Alzheimers/Publications/UnravelingtheMystery/>

The surface of the cerebrum is covered by the cerebral cortex, an intricately folded layer of nerve cells about one-eighth inch thick. The cortex is the brain’s “thinking cap” that receives information from the outside world, analyzes it, makes decisions about it, and sends messages via other brain structures to the right muscles and glands so that we may organize responses to it. It is our large cerebral cortex that sets humanity apart from the rest of the animal kingdom, and which makes it possible for us to adapt to and survive in all manner of environments.

The folds of the cerebrum are known as sulci (“furrows”), and the deepest of these furrows divide the two hemispheres into four lobes which are named after the main skull bones that cover them: the frontal, parietal, occipital, and temporal lobes (see Figure 1.1). The occipital (“back”) lobe is primarily devoted to vision, and need not concern us here. Structures in the parietal (“cavity”) lobes provide us with our unified perceptions of the world by integrating information coming to us from our various senses by cross-matching sensory information with abstract symbols (language) representative of the sum of the sensory input surrounding it. Parietal lobe structures systematize, classify, and consolidate our knowledge and form it into abstract concepts—an ability which, as far as we know, is only possessed by human beings. Structures in the temporal (“temple”) lobe are primarily involved in perception, memory, and hearing. While the parietal lobes integrate information, the temporal lobes’ hippocampi are where these integrations are stored, retrieved, and associated with previous information. This associative process is obviously crucial for learning because we have to assign connotative properties to stimuli in accordance to their significance to us. If we did not associate incoming stimuli with the motivational and affective significance they have for us, behavior would never be modified because all stimuli would treated as more or less equivalent.

The most important of the lobes in terms of the behaviors of interest to criminologists are the frontal (“front”) lobes, particularly the prefrontal cortex (PFC), “the most uniquely human of all brain structures” (Goldberg, 2001:2). The PFC is the terminal point for much of the emotional input from the limbic system, and the origin of our response to it. It is the most anterior portion of the frontal lobe, occupying approximately one-third of the human cerebral cortex, and is the last brain area to fully mature (Romine & Reynolds, 2005). The PFC is subdivided into a number of areas, the most important for our purposes being the orbitofrontal, ventromedial, and dorsolateral areas, and has extensive connections with other cortical regions, with deeper structures in the limbic system, and directly with the RAS, which indicates that it is on a high level of alertness. Because of its many connections with other brain structures, it is generally considered to play the major integrative and supervisory role in the brain, and is vital to the forming of moral judgments, mediating affect, and for social cognition (Romine & Reynolds, 2005; Sowell, Thompson & Toga, 2004).

Neurons

The brain contains at least a trillion cells, and about 100 billion of them are the communicating neurons that give rise to all those cerebral things—intelligence, emotion, creativity, memory—that define our humanity (Mithen & Parsons, 2008). The neuron is the basic unit of the brain, and each one is a fully integrated member of a network of other neurons with a particular set of kinship connections. Neurons are much like other cells in our bodies, containing a nucleus with DNA, ribosomes, mitochondria, and many of the other constituents of somatic cells, but their “specialness” lies in their patterns of connectivity. Although the number of neurons does not appreciably change after birth, the brain itself quadruples in size from neonate to adult. Much of this size increase is attributable to the increase in glial cells. Glial cells are much more numerous than neurons, and their special jobs are to provide neurons with physical support, maintain their homeostasis, and to form the myelin sheath around their axons.

Neurons are specialized for conducting information from one cell to another by transducing stimuli from the environment into electrochemical impulses and transmitting them via the appropriate networks (pathways) of other cells so that a response may be made. They accomplish this by way of axons that originate in the cell body, and dendrites, which are branched extensions of the cell. Axons are coated by a myelin sheath formed by special types of glial cells. Much like the insulation around electrical wiring, myelin functions to protect the axon from short-circuiting and to amplify nerve impulses. Myelinated axons transmit impulses about 100 times faster than unmyelinated axons, and are the brain’s “white matter” as opposed to its “gray matter,” which consists of cell bodies and unmyelinated axons. There is only one axon per cell, but the number of branching dendrites varies from neuron to neuron, and each dendrite may have thousands of tiny projections called dendritic spines. Axons serve as transmitters, sending signals to other neurons, and dendrites serve as receivers, picking up impulses from neighboring neurons which are then passed on to the next neuron in the chain.

Neurons pass their information along the axon in the form of electrical signals made possible by the exchange of charged atoms (ions) in and out of the axon’s permeable membrane. The energy needed to perform the neuron’s activities (as with the activities of all cells in the body) is provided by a chemical called adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is synthesized from dietary proteins, fats, and sugars by mitochondria in the cell body. Impulses travel down axons like neon lights flicking on and off until they reach the axon terminal point known as synaptic knobs, or more simply, synapses. The message is changed from electrical to chemical form at the synapse, at which time neurotransmitters (see Figure 2.1) stored in vesicles open up and spill out into microscopic gaps between the presynaptic axon and the receptors of the postsynaptic cell. After the message is received by the postsynaptic neuron, it may again be converted to electric impulses to continue its journey to the next cell, depending upon the ratio of excitatory to inhibitory messages it receives. A neuron has the capacity to make many thousands of synaptic connections with other neurons, and the brain’s 100 billion neurons “form over 100 trillion connections with each other—more than all of the Internet connections in the world!” (Weinberger, Elvevag & Giedd, 2005:5).

Brain Development and Plasticity

There are debates are about the relative contributions to brain development of processes intrinsic (in the genome) and extrinsic (environmental) to it, albeit not na...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 The Basic Brain

- 2 Neurochemistry, Gene–cultural Coevolution, and Criminal Behavior

- 3 Brain Development, Abuse-neglect, and Criminality

- 4 ADHD, Comorbid Disorders, and Criminal Behavior

- 5 The Age–crime Curve, Puberty, and Brain Maturation

- 6 Substance Abuse Disorders, Epigenetic Plasticity, and Criminal Behavior

- 7 Intelligence, Nature/nurture, and Criminal Behavior

- 8 Schizophrenia, Brain Development, and Criminal Behavior

- 9 Criminal Violence and the Brain

- 10 Gender, Crime, and the Brain

- 11 The Psychopath: The Quintessential Criminal

- Bibliography

- Index