eBook - ePub

The Collaborators: Interactions in the Architectural Design Process

- 262 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Collaborators: Interactions in the Architectural Design Process

About this book

Illustrated by critical analyses of significant buildings, including examples by such eminent architects as Adler and Sullivan, Erich Mendelsohn, and Louis Kahn, this book examines collaboration in the architectural design process over a period ranging from the mid-19th century to the late 1960s. The examples chosen, located in England, the United States, Israel and South Africa, are of international scope. They have intrinsic interest as works of architecture, and illustrate all facets of collaboration, involving architects, engineers and clients. Prior to dealing with the case studies the theoretical framework is set in three introductory essays which discuss in general terms the organizational implications of partnerships, associations and teams; the nature of interactions between architect and engineer; and cooperation and confrontation in the relationship between architect and client. From this original standpoint, the interactive role of the designers, it examines and reinterprets such well-known buildings as the Chicago Auditorium and the Kimbell Art Museum. The re-evaluation of St Pancras Station and its hotel questions common presumptions about the separation of professional roles played by its engineer and architect. The account of the troubled history of Mendelsohn's project for the first Haifa Power House highlights the difficulties that arise when a determined and eminent architect confronts a powerful and demanding client. In a later era, the examination of the John Moffat Building, which is less well known but deserving of wider recognition, reveals how the fruitful collaboration of multiple architects can result in a successful unified design. These case studies comprise a wide range of programmes, challenges, personalities and interactions. Ultimately, in five different ways, in five different epochs, and in five different circumstantial and cultural contexts, this book shows how the dialogue between the players in the design process resonates upo

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

St. Pancras Reconsidered: A Case Study in the Interface of Architecture and Engineering

BRIDGING THE GAP BETWEEN ARCHITECT AND ENGINEER

Most modern commentators agree that by the nineteenth century the professional split between architect and engineer had become institutionalized, and the problem of integration of their diverse skills in the design process and their ultimate synthesis in a unified creation had become acute. The objective historical reasons for this estrangement may have been variously interpreted, but the conclusion almost universally arrived at was that in complex Victorian buildings dependent on large-scale structures, the final divorce of rationality and artistic creation had taken place. Hence Giedion (1941) wrote of ‘the schism between architecture and technology;’ Collins (1965) noted ‘the division between the two professions’ of architecture and engineering which had taken place as early as 1750; and Gans and her colleagues (1991) still perceived the need to ‘bridge the gap’ between architect and engineer.

It is our contention that these strictures are too severe, and that, in the nineteenth century, there was always a potential degree of overlap between architect and engineer, even in the age of complex problems and innovative technology. To stress the schism between the professions in the nineteenth century is to fail to see the relationships, interactions and overlappings—what Peters (1993) calls ‘border crossing’—when they do occur. While not denying the reality of the division of the professions in Victorian building, it is, we believe, far more instructive to look for the areas, if not of active cooperation, then at least of congruence.

In order to do this, we should be looking not at today’s understanding of the nature of engineering and architecture, but rather at the perceptions of the professions prevalent in the nineteenth century itself. Preparatory to the charter of the Institution of Civil Engineers, incorporated in 1828, engineering was defined as ‘the art of directing the great sources of power in Nature for the use and convenience of man.’1 This broad definition, virtually unchanged,2 later became the basis for the interpretation of the role of the civil engineer as one ‘whose field is that of structures’ (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1929/1939). These structures included bridges, highways, dams, harbours, canals and aqueducts. They were interventions by calculation, design and construction, aimed at ‘directing the great sources of power in Nature’, and they constituted the engineer’s traditional areas of competence. With the advent of new unprecedented building types the term ‘structures’ began also to embrace the design and supervision of the construction of great buildings.

This inclusion of great buildings in the engineer’s brief, reflecting nineteenth-century realities, inevitably brought engineering into the time-honoured territory of the architect who, according to Gwilt’s definition (1867), was ‘a person competent to design and superintend the execution of any building.’ This definition, incidentally, has not changed significantly to the present day, except to emphasize the ‘art and science’ of such design.3

It was in the design of non-traditional buildings such as factories, warehouses and railway stations that a grey area emerged, where the roles of the engineer and architect of the mid-nineteenth century overlapped, and the boundaries of their professional competence and responsibility became blurred. Surprisingly, there appears to have been no serious debate, at an institutional level, on the interaction of the two professions, either in the Transactions of the Royal Institute of British Architects, or in the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers.4

There were three facets of the design of buildings where rival claims of engineer and architect could possibly collide: the areas of planning, beauty of form and decoration, and structure. While the dependence of architecture on structure still remained a central tenet in architectural theory, the nineteenth-century architect—lacking the specialized knowledge, training, computational skills, and, perhaps, the temperament of the engineer—was forced in practice to concede the design of large-scale structures, especially those employing non-traditional materials and techniques (first in iron, then steel and reinforced concrete) to the civil engineer. However, while ‘cheerfully obeying structural necessities,’ the architect regarded questions of beauty, ‘adapting the forms suggested by construction into beautiful and harmonious constructions’ as his special prerogative (Jackson, 1885). On the whole, the engineer allowed this claim, sometimes openly acknowledging the architect’s expertise in matters of beauty, more often by default, regarding beauty perhaps as a possible outcome of the engineer’s work, but not its prime aim. As to planning—the shaping, disposition, zoning and connection of the internal spaces of the building—this was undoubtedly the monopoly of the architect, and since the nineteenth century a major determinant of his work. The propriety of this claim to exclusiveness was (but for one significant exception) not seriously challenged by the engineer.

The one exception in which the question of planning was discussed in the engineering literature was the case of the railway station. This was raised in a paper, given to the Institution of Civil Engineers on 27 April 1858 by Robert Jacomb Hood, entitled: ‘On the Arrangement and Construction of Railway Stations.’ Hood considered ‘the correct and judicious arrangement of the terminal and other stations’ to be one of the most important branches of the Railway Engineer’s practice, regretting ‘how limited is the number of stations which can fall to the share of any but a few leading members of the profession, and how much this class of work is usually divided with directors, managers, and architects.’ Despite an acknowledged lack of architectural training from which the British engineer, as compared with his continental counterpart, suffered, Hood (1858) believed the design of the station should nevertheless be the professional responsibility of the engineer.

Many difficulties arise from the practice of employing architects to design and execute the station works. If, therefore, the Engineer desires to do full credit to his employers, and to himself, he should in all cases design the station works, either engaging assistants, or working conjointly with an architect, to furnish the necessary amount of architectural decoration, a talent for which is not always combined with constructive ability, or the faculty of judicious arrangement.

The phrase ‘judicious arrangement’ was the innovation of Hood’s paper, for it raised the question of the proper planning of the railway station as a major thrust of the engineer’s work. The planning requirements of a terminal station were examined in great detail by Hood. These included site planning and access; typologies of layout, concerning ‘the position of the main buildings, relative to the direction of the lines of the rails’; facilities for passenger access and processing, including ‘the most convenient arrangement of the several offices and waiting rooms, with all their accessories’; the movement of trains and the design and construction of the platforms, turntables, traverses, etc.; and the proper provision for ingress and exit, waiting space, and circulation of all categories of vehicular traffic.

This analysis of spatial requirements, design of fittings, pedestrian and vehicular circulation, even heating and ventilation, is exceptional in an engineering publication of that time. It is directly analogous with contemporary papers in architectural journals, which did deal with the planning of complex buildings, such as hospitals.5 The claim made by Hood, that planning (or judicious arrangement) should be in the domain of engineering design, is unique, and is not extended by his colleagues to other building types. There was no direct reaction in the official architectural press to this proposed usurpation of the architect’s role. An indirect response, however, to the activities of the engineer in the design of railway stations, may be found in Alexander J. B. Beresford-Hope’s presidential address to the Royal Institute of British Architects, on 6 November 1865. He questioned the use of the term ‘engineer’ to describe those, not professional architects by training, but architects by their actions, responsible for the design and construction of some of the greatest buildings of the day.

These are the architects who, because the buildings they construct are preeminently massive, because they are mainly devoted to the grand material interests of the nation, because their measurements may be by the furlong and not the yard, therefore abjure the name of the architect to borrow the incongruous appellation of engineer. But it is surely just as incorrect to designate everything that Stephenson or Brunel accomplished engineering, as it would be to call all the works of Michael Angelo [sic] architecture, or painting, or sculpture. The patriarchs of modern engineering have mapped the roadways, invented the rolling stock, and designed the buildings, all of which in different ways go to make up a working railroad, just as an old architect may have built, painted, and carved a cathedral or public hall. The old architect thus showed himself to be architect, painter, and sculptor. So the civil engineer proved himself to be a surveyor, in laying out the line; an engineer, properly so called, in constructing the engines; and an architect, in designing viaducts and stations.

It is interesting to note that Beresford-Hope, as his example of the ‘architectural’ work of the great engineers, chose the railway station, nor did he deny their architectural quality.

In the ambitious pre-emptive claims of Hood, and the generous, if somewhat condescending, praise of Beresford-Hope, we see the seeds of possible congruities in the work of architect and engineer on major construction projects of the nineteenth century. Such congruities are sometimes the result of the innate sensibilities of the designer, be he engineer or architect. On the other hand, as Billington and Mark (1984) have argued, talented engineers such as Roebling or Eiffel ‘did not derive their designs from positivistic science or any belief that efficiency and economy alone would lead them to appropriate forms … but … designed by combining passion with discipline’; and conversely, architects such as Dankmar Adler or Henri Labrouste took architectural decisions shaped to no small extent by the rational imperatives of materials, construction, or the environmental sciences.

More typically, when a degree of congruence between architecture and engineering was achieved, it was a result of necessity as well as mutual understanding. We believe that such creative interaction did occur, even when it was not always visible to the eye. Three major works in Victorian London, each in its own way, demonstrate this thesis. The Palace of Westminster, although it was heavily dependent on elaborate systems of heating and ventilation which made possible the internal location of the debating chambers and which generated some of the vertical emphases of the building, nevertheless maintained the integrity of the architecture as Barry and Pugin conceived it. In the Crystal Palace, it was the ingenious meshing of the 24–foot structural module, the resultant of the engineer’s design of the iron frame, with the 8-foot planning module generated by Paxton’s concept of prefabricated wall panels and glazed roofing system, which gave the building its unified, and unique, architectural character. The third example constitutes our case study, and it is one generally regarded as an extreme example of the perceived conflict of architect and engineer: the design of St. Pancras Station in London, its train shed, and its associated Midland Hotel. In view of the centrality of the railway station in nineteenth-century perception of the role of engineer and architect, it is perhaps the most appropriate example of all.

CASE STUDY: THE RAILWAY STATION

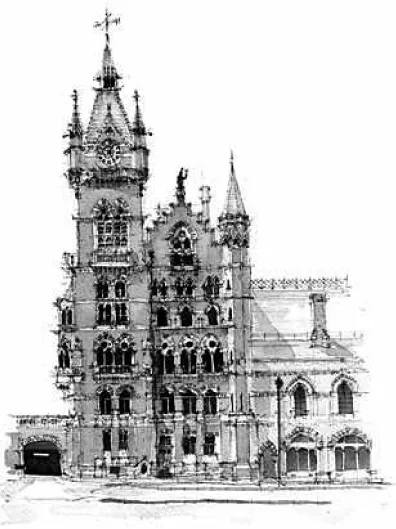

It is generally acknowledged that the complex building known as St. Pancras Station, London, actually comprises two discrete functional units: the train shed for the Midland railway designed by the engineer William Henry Barlow, and the Midland Hotel designed by the architect George Gilbert Scott.

Traditional criticism, moreover, holds that these two conjoined elements stand in direct contrast to each other, in terms of their design approach, their use of technology, and their expressive intent. As Hitchcock (1958) put it, in discussing the two components of St. Pancras: ‘Such a drastic divorce of engineering and architecture could hardly be expected to produce a coordinated edifice.’ Summerson (1970) sees this as a general condition, asserting that ‘after Paddington, the divorce between architect and engineer was complete’, and in the specific case of St. Pancras, he describes this divorce in even more categoric terms, as ‘the disintegration of architecture and engineering: the total separation of functional and ‘artistic’ criteria, in separate heads and hands.’ This assertion, that the two components of St. Pancras co-exist unhappily, has as Curl (1973) once remarked, ‘has been repeated ad nauseum.’

Now, of course, there is a certain amount of truth in this conventional wisdom. Barlow’s great train shed is indeed a triumph of rational design, exploiting to the full the most advanced technology of the day, and expressing the new structural means in a dramatic and lyrical enclosure of space; a space, however, which in its own time was hardly expressive of ruling tastes but could be seen rather as a somewhat stark anticipation of an unpalatable ‘non-artistic’ future. Scott’s neo-Gothic hotel, on the other hand, seems to exemplify a design approach nostalgically reminiscent of a former time and age, where associational, formal, and decorative goals predominate, and whose architectural expression belies any constructive means other than the traditional building crafts.

While not disputing that there is some truth in these generalizations, we argue here that they are greatly over-simplified, and if accepted at face value could lead to false conclusions. It is our intention, therefore, to return to a proposition originally put forward by D. T. Timmins (1902) that the hotel ‘is an integral part of the station itself, and therefore cannot be treated of separately.’ Consequently, we propose to examine each of the components of St. Pancras Statio...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction: Players in the Design Process—Three Essays

- 1 St. Pancras Reconsidered: A Case Study in the Interface of Architecture and Engineering

- 2 Speculations on a Black Hole: Adler & Sullivan and the Planning of the Chicago Auditorium Building

- 3 Clash of the Titans: Rutenberg, Mendelsohn, and the Problem of Client-Architect Relationships

- 4 Working as a Team: From the Transvaal Group to the John Moffat Building

- 5 Kahn, Komendant, and The Kimbell Art Museum: Cooperation, Competition, and Conflict

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Collaborators: Interactions in the Architectural Design Process by Gilbert Herbert,Mark Donchin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.