eBook - ePub

Social Media in Travel, Tourism and Hospitality

Theory, Practice and Cases

- 338 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Social Media in Travel, Tourism and Hospitality

Theory, Practice and Cases

About this book

Social media is fundamentally changing the way travellers and tourists search, find, read and trust, as well as collaboratively produce information about tourism suppliers and tourism destinations. Presenting cutting-edge theory, research and case studies investigating Web 2.0 applications and tools that transform the role and behaviour of the new generation of travellers, this book also examines the ways in which tourism organisations reengineer and implement their business models and operations, such as new service development, marketing, networking and knowledge management. Written by an international group of researchers widely known for their expertise in the field of the Internet and tourism, chapters include applications and case studies in various travel, tourism and leisure sectors.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Social Media in Travel, Tourism and Hospitality by Evangelos Christou, Marianna Sigala in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Hospitality, Travel & Tourism Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Web 2.0: Strategic and Operational Business Models

Chapter 1

Introduction to Part 1

1. The Integration and Impact of Web 2.0 on Business Operations and Strategies

During the last few years, we have experienced the mushrooming and increased use of web tools enabling Internet users to both create and distribute (multimedia) content. These tools referred to as Web 2.0 technologies can be considered as the tools of mass collaboration, since they empower Internet users to actively participate and simultaneously collaborate with other Internet users to produce, consume and diffuse the information and knowledge being distributed through the Internet. As information is the lifeblood of the tourism industry, Web 2.0 advances are having a tremendous impact on both tourism demand and tourism supply.

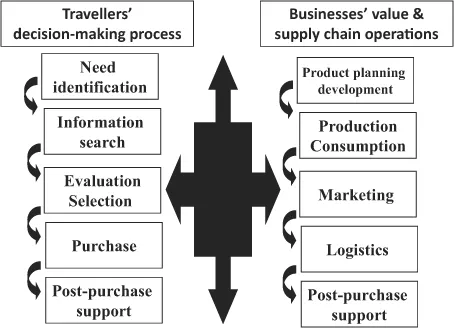

Web 2.0 is fundamentally changing the way travellers and tourists search, find, read, trust as well as (collaboratively) produce information about tourism suppliers and destinations (Cox et al., 2009). Moreover, Web 2.0 applications such as collaborative trip planning tools, social and content sharing networks as well as massive multi-player online social games such as Secondlife, empower travellers to get engaged with the operations of tourism firms (for example by designing and promoting a cultural trip/event). In fact, Web 2.0 affects all stages of the travellers’ decision-making process (see Figure 1.1) in terms of the way travellers identify and realise that they have a need, for example user-generated content, UGC, is found to have an AIDA effect on travellers by creating attention, interest, desire and action (Pan et al., 2007); the sources that travellers use for searching and evaluating travel information (Kim et al., 2004); the channels that travellers use for booking and buying travel products, changing travel reservations and itineraries after purchase as well as for sharing and disseminating experiences and feedback after the trip (Yoo and Gretzel 2008). Overall, Web 2.0 transforms travellers from passive consumers to active prosumers (producers and consumers) of travel experiences, while changing the way in which travellers develop relations, their perceived image of and loyalty to, tourism firms (Christou 2003 and 2010).

In this vein, travel and tourism companies are currently changing and redefining their business models in order to address the needs and expectations of this new generation of travellers. Tourism firms are also trying to more actively involve travellers with their business operations in order to benefit from and exploit the intelligence and social influence of travellers’ networks. In other words, Web 2.0 presses but also enables tourism firms to change the ways in which they traditionally conduct their internal and external business operations in order to integrate customers as a more active stakeholder of their business models. As a result, Web 2.0 has tremendous transformation power on the firms’ value and supply chain operations (see Figure 1.1): more and more tourism firms exploit UGC and/or involve travellers’ with their new Service Development (NSD) processes (i.e. travellers as co-designers) (Kohler et al., 2011); travellers’ and their social networks play a more active role in the production and consumption of tourism experiences by influencing the way travellers design and perform their travel experiences (i.e. travellers as co-creators) (Sigala 2010); travellers and their social networks are being increasingly exploited for creating a positive image for a tourism firm, promoting and distributing its services (i.e. travellers as comarketers and co-distributors) (Sigala 2011); and travellers’ post-trip experiences and feedback are exploited for improving services as well as supporting other travellers to design their future trips.

Figure 1.1 Web 2.0 Affects the Whole Process

Nevertheless, tourism firms differ in terms of the level and the degree to which they are integrating travellers into their operations. Similarly to the take-up of any technology, the adoption and exploitation levels of Web 2.0 by tourism firms are affected by numerous factors that are either internal to the firm (e.g. size of the firm and management commitment) and/or external to the firm (e.g. culture of travellers, see for example, Christou 2005). In this vein, it is not only interesting but also useful to study the diffusion level as well as the factors influencing the latter in order to better inform and support the tourism industry on how to fully and better exploit Web 2.0.

2. Overview of the First Part of the Book

The overall goal of the first part of this book is to provide practical examples and theoretical underpinnings on how tourism firms integrate and exploit Web 2.0 in their value and supply chain operations. The chapters in this part also aim to examine and give insight into the factors that can facilitate and/or inhibit the adoption of Web 2.0 technologies. Thus, the individual chapters offer useful practical implications to tourism professionals wishing to more effectively exploit Web 2.0.

Chapter 2 by Evangelos Christou and Athina Nella, analyses how Web 2.0 enables cooperation, networking and knowledge exchanges/dissemination amongst the various wine tourism stakeholders, such as wine tourists, wine clusters, wine tourism DMOs or tour operators, wine producers and distributors. To achieve that, the chapter analyses two Web 2.0 enabled wine networks, namely:

• the wineandhospitalitynetwork.com, a global network linking professionals of the wine and hospitality sectors, i.e. wineries, sommeliers, oenologists and other stakeholders of wine tourism destinations;

• the greatwinecapitals.com, a network of nine global wine tourism destinations that seek to create synergies, value and knowledge exchange for stakeholders of the member cities.

Chapter 3 is written by Marianna Sigala and investigates the ways, the benefits and the disadvantages of utilising Web 2.0 to involve customers with NSD processes. To achieve this, the chapter reviews and synthesises the related literature as well as analysing two case studies to show how two tourism firms are exploiting Web 2.0 for NSD practices: a) the social network of www.mystarbucksidea.com developed by Starbucks for engaging consumers with new service ideas generation and evaluation; and b) the exploitation of secondlife.com by Starwood to enable users to design, test and promote a new hotel concept namely, Aloft hotels. The chapter concludes by providing a holistic framework for studying customer involvement in NSD as well as practical implications and suggestions on how tourism firms can fully exploit the potential of Web 2.0 for NSD.

Chapter 4 is written by Jim Hamill and Alan Stevenson and presents a detailed case study of a local tourism industry collaborative effort aimed at building brand awareness and ‘buzz’ using the full potential of social media – the Merchant City (Glasgow) ‘Creating the Buzz’ Social Media Project. The case study shows that while a number of key project targets were met, organisational, people and internal political issues prevented the full realisation of expected project benefits. The chapter identifies and analyses the lessons that were learned from the case study and which are useful to other tourism networks embarking on similar collaborative social marketing efforts.

Chapter 5 is written by Daniel Hee Leung, Andy Lee, and Rob Law and examines how hotels can exploit Web 2.0 to enhance the design and functionality of the hotels’ websites. Drawing on the findings from a content analysis of hotel websites and interviews with the hotel managers based in Hong Kong, the chapter also discusses the association between brand affiliation and the adoption of Web 2.0 technologies.

References

Christou, E. 2003. On-line buyers’ trust in a brand and the relationship with brand loyalty: The case of virtual travel agents. Tourism Today, 3(1), 95-106.

Christou, E. 2005. Promotional pricing in the electronic commerce for holiday packages: A model of purchase behavior, in Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2005, edited by A.J Frew. Vienna: Springer Verlag.

Christou, E. 2010. Relationship marketing practices for retention of corporate customers in hospitality contract catering. Tourism & Hospitality Management: An International Journal, 16(1), 1-10.

Cox, C., Burgess, S., Sellitto, C. and Buultjens, J. 2009. The role of user-generated content in tourists’ travel planning behavior. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 18, 743-764.

Kim, W.G., Lee, C. and Hiemstra, S.J. 2004. Effects of an online virtual community on customer loyalty and travel product purchases. Tourism Management, 25, 343-355.

Kohler, T., Fueller, J., Stieger, D. and Matzler, K. 2011. Avatar-based innovation: Consequences of the virtual co-creation experience. Computers in Human Behaviour, 27, 160-168.

Pan, B., MacLaurin, T. and Crotts, J.C. 2007. Travel Blogs and the Implications for Destination Marketing. Journal of Travel Research, 46, 35-45.

Sigala, M. 2010. Measuring customer value in online collaborative trip planning processes. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 28, 418-443.

Sigala, M. 2011. eCRM 2.0 applications and trends: The use and perceptions of Greek tourism firms of social networks and intelligence. Computers in Human Behavior, 27, 655-661.

Yoo, K-H. and Gretzel, U. 2008. What motivates consumers to write online travel reviews? Information Technology & Tourism, 10, 283-295.

Chapter 2

Web 2.0 and Networks in Wine Tourism: The Case Studies of greatwinecapitals.com and wineandhospitalitynetwork.com

1. Introduction

Networks can act decisively for synergies and value creation in many sectors of the economy and wine tourism is not an exception. As Bras et al. (2010, p. 1639) state, “the fact that the tourism sector is composed of a diversity of services and resources, all of which contribute to the visitor’s experience, enhances the need to have a destination management network that includes all regional stakeholders”. Additionally, Buhalis and Kaldis (2008) and Sigala and Chalkiti (2007) emphasize the need for networks and clusters to define clear objectives enabling immediate access to various sources of information for all partners involved. The creation of wine tourism networks can lead to prompt and flexible reactions to market trends, increased efficiency and competitiveness while being a safe way to avoid all the drawbacks of centralized organizations (Dodd 2000; Sigala 2005). This can be achieved mainly through knowledge exchange and better coordination of activities among different wineries, wine tourism destinations and other key wine tourism stakeholders (Brown et al., 2007).

The value that wine tourism networks create significantly affects the supply side of wine tourism. Experience has shown that wine tourism stakeholders can share knowledge and experiences on best practices, work on solutions to similar problems they face and find partners with high expertise on wine, marketing and hospitality issues from all over the world (Alebaki and Iakovidou 2011). Moreover, they can collaborate in order to design better services and provide satisfactory tourism experiences or even establish common benchmarks for the improvement of their services (Roberts and Sparks 2006; Nella and Christou 2010; Sigala and Chalkiti 2008). The collaboration of wine tourism stakeholders into a regional or global network can create synergies not only for the improvement of their operations and services, but also for their communicational and promotional efforts.

Wine tourism networks may also benefit the demand side, i.e. the wine tourists or, more broadly, the wine-interested consumers. Wine consumers and tourists can be significantly assisted in evaluating information for particular wine varieties, wine brands and wine tourism destinations (Yuan et al., 2006; Kolyesnikova and Dodd 2008). Moreover, their interest in wine tourism could be further stimulated if well organized tourism experiences are offered to them on behalf of the members of the network.

Despite their importance and value, there is still great potential for network creation and expansion in the wine tourism sector, both locally and globally. Buhalis and Kaldis (2008) suggest that networks and clusters should exploit new technologies in order to increase interaction and collaboration. One area of improvement for wine tourism networks is to further exploit social media, since, “the wine industry is notoriously slow at embracing new technologies … although, especially in this industry, social media are predicted to evolve into social commerce”.1 Even today, there are many wine and wine tourism organizations that restrict their activities to the use of a sole website and the traditional one-way communication model (Christou et al., 2009).

Social media allow real time information sharing among network members, thus vastly facilitating communication, knowledge exchange, social interaction and collaboration not only at the regional and national level but globally as well (Rocha and Victor 2010; Sigala 2008). Moreover, Web 2.0 applications, due to the interactivity element that they offer can enhance the interest and engagement of current members. It is also easier for potential new members to be informed about the existence and the value of a network and evaluate whether to join it or not. Social media help to overcome the distance barriers and other communication obstacles.

Social media can also play a crucial role for consumer behavior towards wine. If we take for granted that community opinions can be more influential for intentions compared to advertising messages or professional reviews for wines, we realize the great impact that social media could have for brand awareness, brand acceptance, trial and other behavioural intentions. Quite apart from that, social media platforms and user generated content can contribute to creating or increasing the interest and engagement of wine consumers for a wine producing destination, a winery, a wine variety or a wine brand (Sigala 2006; Gill et al., 2007; Sigala 2010). If we accept that social media are playing an increasingly important role as information sources for travellers (Xiang and Gretzel 2010), we can realize the great potential that is untapped for wineries, wine festival organizers and wine tourism destinations (Christou and Nella 2010). Last but not least, social media can assist the members of wine tourism networks to gather valuable information on the profiles, motives, perceptions and attitudes of wine consumers and tourists.

Obviously, Web 2.0 enables every stakeholder to network (Sigala and Chalkiti 2011). There are different types of wine tourism stakeholders who may benefit from networks, e.g. wine tourists, DMO’s, clusters of wine producers etc. Various types of Web 2.0 social networks can be utilized according to the type of stakeholders. In this chapter, emphasis is put on business networks relating to wine tourism: two interesting cases of networks that, apart from creating significant value for their members, have eagerly utilized Web 2.0 tools (social media, blogs and online forums) in order to enhance their efforts are:

• wineandhospitalitynetwork.com: a global network linking professionals of the wine and hospitality sectors, i.e. wineries, sommeliers, oenologists and other stakeholders of wine tourism destinations.

• greatwinecapitals.com: a network of nine global wine tourism destina...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- New Directions in Tourism Analysis

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Contributors

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Introduction

- Part 1 Web 2.0: Strategic and Operational Business Models

- Part 2 Web 2.0: Applications for Marketing

- Part 3 Web 2.0: Travellers' Behaviour

- Part 4 Web 2.0: Knowledge Management and Market Research

- Index