![]()

1 A Parisian Apprenticeship

It was in autumn of 1943 that Pierre Boulez arrived in Paris to enrol as a student at the Conservatoire. Yet, limited though his musical horizons may have been in wartime France, he was already a fledgling composer, having written assiduously over the previous year. With one exception, the sonata for violin and piano, the pre-Paris works fall into the categories of solo piano and accompanied mélodies. The most impressive, if not the most ambitious, of these works is a short piano piece, Psalmodie. The movement has a curious history: the manuscript was in a private collection until 1983 when it was acquired by the Bibiothèque nationale de France (BNF). In the previous year, it was evidently first offered to the composer himself, whose amusing response is of some interest in revealing the mature composer’s attitude to his student compositions:

To tell the truth, I think that this ancient piece must live its own existence, having left me so long ago. It would be like trying to graft a dead leaf onto a tree which is still green.

I would not therefore consider acquiring it for myself …1

The manuscript bears the dedication, ‘To my dear master L. de Pachmann2 from his respectful and grateful student P. Boulez’,3 and is dated September 1943. To judge from the style of this final offering to his piano teacher in Lyon, the young musician already felt a strong affinity with the music of Debussy and Ravel, and has recalled specifically the influence of the Prelude La puerta del Vino.4 The languid opening avec douceur recalls the Prelude’s Habanera rhythm, whilst the piano figuration of the contrasting mid section suggests a possible acquaintance with the pianism of Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin. If elsewhere the sequences are rather predictable, and the texture of parallel harmonies over a sustained bass somewhat conventional, the ambiguous tonality of the final bars strikes a personal note and the stirrings of an exploratory turn of mind.5

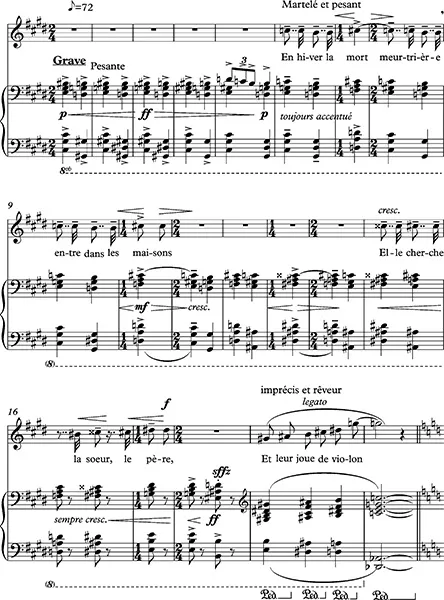

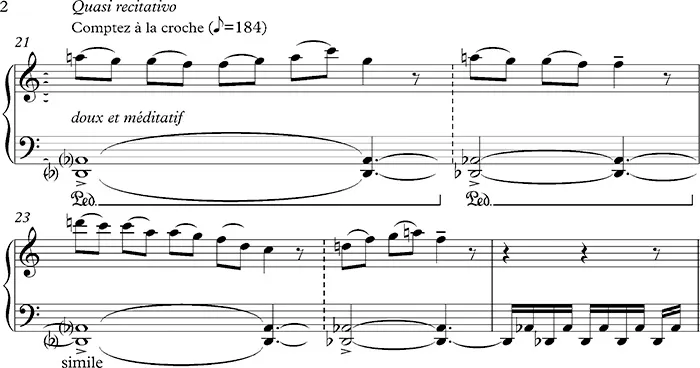

The Psalmodie is in effect Boulez’s signing-off piece in terms of his musical experiences during his period in Lyon, and is almost exactly contemporary with the final song of a set of three poems by Rainer Maria Rilke for voice and piano. The first two of these, Après une journée de vent and La Mort were completed respectively in April and May 1943, whilst La Passante d’Eté was evidently finished in October, the month after Psalmodie, and (presumably) just before his departure for Paris. If the choice of poetry and indeed the musical style reflects the young composer’s impressionist sympathies, the settings themselves show considerable imagination and poetic sensibility. Word painting is a feature of all three songs: in La Mort, the image of Death luring his victims by seductive phrases on the violin is evoked in an extended piano interlude marked doux et méditatif. Among the impressive features of this setting is the declamatory vocal line in the opening section set against the relentless dissonances of the chordal accompaniment (Example 1.1):

Boulez evidently had second thoughts about the ending, since an extra bar in the pencil manuscript was omitted from the pen copy of the song. The revised ending creates its own sense of foreboding at Death’s unfinished business, but the extra bar, consisting of the dominant chord with an added major seventh, is still more stark in defining its kinship with the tonic/leading note clashes of the opening phrase of the song. The slightly earlier Après une journée de vent is a charming depiction of evening calm after a turbulent day. In style, it is the most traditional of the three settings, being heavily reliant on whole tone harmonies, and indeed the tonal ambiguity of the ending recalls Debussy’s Voiles. Most successful of all is the final song, La Passante d’Eté, whose pastoral character bears some resemblance to that of Après une journée de vent. However its greater range of texture and more advanced harmonic vocabulary testify to the speed with which the young composer was developing. The promenading lady is portrayed in a chordal phrase whose dissonant harmonies resulting from the parallel motion between the hands had been anticipated in the setting of La Mort. At the end of La Passante d’Eté, the much admired woman evidently continues her promenade, as the song ends with the same tonally ambiguous chordal progression as had greeted her original entrance.

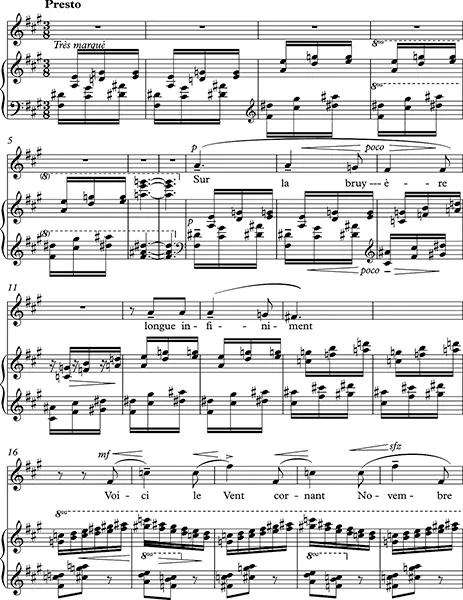

It is worth noting in passing that the most ambitious vocal setting of this period remained unfinished. Boulez worked on a setting of Emile Verhaeren’s extended poem Le Vent, completing six sides of a pencil draft, the final page of which is on the verso of La Passante d’Eté, suggesting that work on it is likely to have been abandoned prior to his departure for Paris in the autumn of 1943. The virtuoso pianism of the accompaniment with its alternating hands and rapid scales in thirds has a Scarbo-like character, whilst the uncompromising bitonality of the climax, where F major and F-sharp major chords are opposed, recall the atmosphere of Szymanowski’s Mythes, a work which is known to have impressed him at this time (Example 1.2):6

Clearly, a range of stylistic influences were being absorbed at a rate which suggests that, in purely musical terms, the young composer was more than ready to move away from his provincial roots.

* * *

Boulez’s years at the Conservatoire National de Musique are as yet lacking detailed documentation, but it is likely that among his first experiences in Paris were the admission auditions for the Classes de Piano Supérieur at the Conservatoire, which took place on 13–14 October 1943.7 The auditioning was conducted rigorously, with each of the twelve members of the jury given a vote, and the proceedings were chaired by the Director, Claude Delvincourt. Boulez was one of the last to be auditioned (no. 119 of 124), on the early evening of 14 October, and failed to attain the minimum of six votes required for admission to one of the piano classes. As a result, one of his first musical experiences in Paris ended in failure, and he was not listed among the fifty-one students admitted to these courses. More successful was his experience in the examination for admission to the Harmony Class of M. Georges Dandelot, which took place on 17 January 1944, and which he passed with the comment ‘Bien’. Boulez’s progress was so rapid that in M. Dandelot’s report of May 1944, Boulez is described by as ‘… the best of the class …’,8 and with the additional comment: ‘… has nothing further to learn at first degree level …’9 Of greater significance in terms of Boulez’s future trajectory was a contact made during these months. Among the other eighteen students registered in M. Dandelot’s large class was a Mlle Vaurabourg – none other than Annette, the niece of Andrée Vaurabourg, wife of the composer Arthur Honegger.10 Evidently, it was through this connection that Boulez was introduced to Andrée Vaurabourg-Honegger, with whom he commenced private lessons in counterpoint, beginning in April 1944 and extending over a period of some two years.11

Recent research has enabled precise dating of Boulez’s first direct contact with another crucial pedagogical influence – Olivier Messiaen.12 An initial visit to Messiaen’s apartment on 28 June 1944 was followed by enrolment in his Harmony class at the Conservatoire for the academic year 1944–5. Further evidence of an immediate rapport between the student who ‘… likes modern music, wants to take harmony lessons from me…’13 and the composer of the recently completed Visions de l’Amen, is provided by the fact that Boulez evidently re-visited Messiaen’s apartment on four subsequent occasions prior to his formal enrolment in the class: on 10 July, 11 August, 23 September and 6 December.14 It was two days after this final appointment that Boulez first attended one of Messiaen’s private classes for the group known as Les Flèches, where he would have come into direct contact with Yvonne Loriod and Yvette Grimaud, both important figures in the performances of his earliest published works. Later that month, Loriod gave two pieces from Messiaen’s recently completed Vingt Regards cycle in a recital at the Conservatoire, and there is every reason to assume that Boulez would have been aware of the new work, and even attended the concert. In the meantime, having finally abandoned his pianistic ambitions, at least through the official Conservatoire route, Boulez was inspired to resume his own compositional activities. The result was a profusion of works for solo piano produced over the next few months.

The young composer’s attendance at Messiaen’s Harmony Class at the Conservatoire began with his formal enrolment on 23 January 1945, and among others who enrolled on the same day was Pierre Henry.15 Otherwise, the list of enrolled students makes for sombre reading, including as it does, three students who had been enrolled since 1942 but unable to attend, having been taken prisoners of war – a reminder of the unstable background to the young Boulez’s formative years. The end of year examination took place on 11.06.45, and Boulez was described in the examiners’ report as ‘… the most gifted – a composer …’16 He was one of four students awarded premier prix, and the only one from Messiaen’s class to achieve this distinction. At this point, Boulez evidently left the class: a comparatively brief, but decisive encounter.

* * *

The principal products of this period of study with Messiaen and Vaurabourg-Honegger are dominated by two triptychs for solo piano, P...