- 210 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Legislative and institutional affirmative and positive action policies, intended to increase accessibility and the participation of historically disadvantaged groups in employment and education, have been with us for some time, particularly in Anglo Saxon countries. One of the major issues they are intended to address is gender inequality. Proponents of these policies have hailed quota initiatives as a key to promoting equal opportunities and reducing discrimination. At the same time, affirmative action policies and processes have been challenged in courts and have caused controversy in educational establishments, highlighting the fact that these practices can have negative consequences. Exploring the application of quotas and affirmative action at an institutional or organizational level from a variety of different perspectives, the contributions in Diversity Quotas, Diverse Perspectives provide an understanding of the complexity and controversial nature of policies and actions in different countries. Even within Europe, implementation has varied widely from country to country. For example, while most European countries have employment quotas for people with disabilities, there is little consistency among the European Union's member states when it comes to quotas and other policies relating to ethnic minorities in employment and educational settings. Focussing here particularly on gender-related initiatives, but raising questions pertinent to other aspects of diversity, the contributions from international researchers investigate variances between and differing justifications for policies. The book offers a global perspective on the subject and expands the discussion of it beyond Anglo-Saxon contexts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Diversity Quotas, Diverse Perspectives by Stefan Gröschl,Junko Takagi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Quota Systems in Different Cultural Settings

CHAPTER 1

The ‘Golden Skirts’: Lessons from Norway about Women on Corporate Boards of Directors

Introduction

Norway is considered one of the most progressive countries with regards to increasing the number of women on boards – thanks to it being an early adopter of legislation to force companies to recruit women to the boardroom. To many feminists, this is the boldest move anywhere to breach one of the most durable barriers to gender equality – The Female Factor.

In 2003, amendments to the Public Limited Companies Act in Norway provided for a requirement for a certain minimum proportion of directors from each gender. This has led to a dramatic increase in the number of women on boards of Norwegian companies. Other countries looking to adopt an enforced quota scheme are looking at the results in Norway and plan accordingly.

The role of women in society is changing. This is not only in the public and private sector, but also in the business world. These changes are found in many countries, but the speed and focus may vary. There are various arguments to develop ways to increase the number of women on corporate boards of directors. Corporate boards of directors have traditionally been seen as meeting places for societal and business elites. The boards have been considered as arenas where the interests of the ‘old boys’ network’ are promoted, and it has been argued that an invisible glass ceiling is hindering women to get into board and top management positions. Several initiatives for getting women into corporate boards have thus been presented (Vinnicombe et al., 2008).

This chapter concentrates on ways to increase the number of women on corporate boards. And the focus is on lessons learnt from recent developments in Norway. I will present reflections about the results being achieved after a law reform was made with the objective to have 40 per cent of the board members coming from the least represented gender. This has in practice been a law forcing the largest Norwegian corporations to have at least 40 per cent women among the board members. The observations will be about the effectiveness of various programmes or means to increase the number of women on corporate boards, and there will be reflections on consequences for businesses and the individual women becoming board members.

WHY BALANCED GENDER REPRESENTATION?

There are various arguments for increasing the number of women on corporate boards – for example societal arguments, individual career arguments and business case arguments.

The societal case arguments have typically been the starting point for much of the attention to the question, and these are also behind the most far-reaching initiatives to increase the number of women on corporate boards. The societal case arguments are about justice in society, democracy, participation, gender equality and the follow up of various international conventions, for example, UN conventions, human rights and European Union (EU)/ European Economic Area (EEA) conventions. The individual case arguments or the career arguments are often related to the ‘glass ceiling’ discussions. The business case arguments are about why and how women on corporate boards will improve firm performance. These arguments have particularly been emphasized in contexts where the societal case arguments are not accepted. The main business case arguments are about diversity (that women are different from men), about the use of existing knowledge (that women represent 50 per cent of the knowledge-base in society), about customer relations and understanding customers (that women in many sectors are the main customers), and that men on corporate boards often are too passive.

In the international and national debates the different arguments are often unconsciously mixed. The reasoning and logics behind different initiatives have often suffered from this mixing-up. When an initiative is evaluated it should be done based on the objective for it. If the objective is power balance in society, then the initiative should not only be evaluated based on individual career possibilities or firm performance. These criteria should be considered, but the main evaluation criteria should be societal.

The rest of this chapter is outlined as follows. In the following section we describe the Norwegian case looking at initiatives to increase the number of women directors on corporate boards. This is followed by a section describing the business case for women on boards. The next section describes some results from a study about the ‘golden skirts’ – the women that have made a living from being independent directors. This is followed by a section that reflects on the quota law discussion in relation to the mainstream recommendation about corporate governance practices. In the final section a summarizing conclusion with recommendation is presented.

Norway – the Societal Case: Initiatives and Innovations to Increase the Number of Women Directors

During recent decades several initiatives and innovations have been made to achieve balanced gender perspectives and to increase the number of women in power positions in society (Vinnicombe et al., 2008). In some countries – like Norway – public policies were made at an early stage to have women represented in the public bureaucracy, governmental committees and on the board in state-owned enterprises. Several political parties also made commitment to have women in leadership position – resulting in a large ratio of women in top political positions in Norway.

International discussions about why and how to increase the number of women on corporate boards can also be traced back more than 30 years. Various initiatives and programmes have been considered. They include political arguments, the development of women networks, the financing and dissemination of research, courses and education for preparing women for board work, mentorship programmes, data registers and other sources of communicating to potential women candidates. Suggestions for setting requirements on the number of women directors through soft as well as hard laws have also been promoted.

The different initiatives have various objectives. Some are directed towards educating or preparing women, some are directed towards motivating those selecting board members, and some initiatives are directed towards facilitating the recruitment process. The effectiveness of the different programmes should be evaluated according to the objective of the specific programme. The effectiveness in relation to increasing the number of women on corporate boards will often be a result of a combination of various programmes (educating programmes, motivating programmes and facilitating programmes). The effectiveness will furthermore depend on various contingencies such as the actors involved and the context within which the programme is developed and executed.

A presentation of boards and corporate governance in Norway is found in Rasmussen and Huse (2011). Norway has a two-tier corporate governance system. However, the executive level is normally not a board, but only one person. Board members are typically non-executives. Norway has also a system where one-third of the board members can be elected by and selected from the employees. Furthermore, Oslo Stock Exchange is dominated by state ownership.

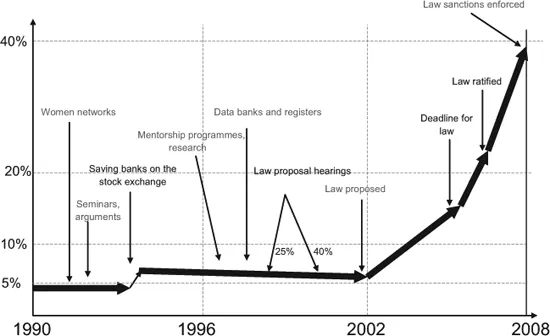

In Figure 1.1 we find an example from Norway illustrating the effectiveness of various programmes to increase the number of women on boards.

Figure 1.1 Effects of programmes: an illustration from Norway

Figure 1.1 reports the percentage of women on the boards of large corporations in Norway. Figures from 1990 to 1998 are from firms listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange. Figures after 1998 are ASA companies (publicly tradable companies). The ASA form of incorporation was established in Norway in 1998. ASA-incorporated firms are generally the largest companies. The figures reported on women are almost constant, around 5 per cent from 1990 till 2002. No increase took place even though considerable efforts were placed on initiatives such as women networks, seminars and arguments, mentorship programmes, research, data banks and registers on women aspiring to board positions. Two public hearings on law proposals also took place, but no increase in the percentage of women on corporate boards was achieved. The only change displayed before 2002 was around 1994. This change was caused by new types of firms (mainly saving banks) being introduced to the Oslo Stock Exchange.

However, we see an incredible increase from 2002 to 2008 – from 6 per cent to almost 40 per cent. In 2002 a law was proposed by the Norwegian Parliament that all ASA-incorporated firms should have gender balance. Each gender should hold at least 40 per cent of board positions in ASA firms. The ASA firms had a few years to implement this requirement voluntarily – otherwise the law would be ratified and enforced. The enforcement of the law began in the beginning of 2008, but by then all ASA companies (with only very few exceptions) had already met the requirement.

The number of board positions in ASA companies has been reduced from 2007 to 2010 – financial companies were no longer required to have the ASA form of incorporation. Several financial companies thus decided to move from the ASA form of incorporation to the AS form (AS are firms not being publicly tradable). The numbers of board positions held by women and men in this period were 1,061 women/2,067 men in 2007, 1,044 women/1,684 men in 2008, 915 women/1,501 men in 2009 and 906 women/1,419 men in 2010.

The Business Case: Gender Diversity and Board Value Creation

Is the law good for businesses? It is so far impossible to present statistical data about the legal enforcement’s consequences on business performance. The research question has until now been if women on corporate boards contribute positively to firm performance – regardless of how women have achieved these positions (Terjesen, Sealy and Singh, 2009). The main business case arguments for women directors are that they bring diversity into the boardroom. Diversity is in this reasoning assumed to be important for board effectiveness. However, we do not even have clear evidence telling that diversity in general – and gender diversity in particular – contributes to board effectiveness. It can be argued that there are no direct relationships between competence and diversity on the one hand, and board effectiveness and value creation on the other (Huse, 2008). Board effectiveness depends on the boards’ working style and decision-making culture, and on board leadership (Huse, 2007).

To respond to these research questions we need to clarify what we mean by a board of directors. Do we argue about supervisory or executive boards, or is it about unified boards? And for what kinds of firms? Huse (1994, 2007) identified four different typologies and their respective bodies of theories including:

• aunt boards where nobody considers the board to play any role;

• barbarian boards where independent board members exercise their power;

• clan boards where the board members are protecting their own privileges;

• value-creating boards where board members are involved in developing the company.

The different types of boards will have different working styles, different types of competencies will be emphasized, and value creation will have different interpretations.

Further, what do we mean by diversity? Diversity has something to do with the board members as a group. Diversity and competence are not the same. And what do we mean by good? We may talk about value creation, but it depends on with whom we talk about value creation and what kind of value creation.

When exploring boards we need to understand that there are various actors that work in different arenas. We need to know who the actors are (internal, external or board members), the diversity, knowledge and skills, and who the board members identify themselves with. The arenas may be formal and informal, and not all arenas are open to everybody. The relationships between the various actors are characterized by trust and emotions, and of power and strategizing.

SOME EMPIRICAL STUDIES FROM NORWAY

The few studies that have been done on the contribution of women directors to board or firm effectiveness have given mixed results (Huse, 2008). Some studies conclude that women have made positive contributions, while others conclude that negative or no contributions have been made. A common problem with most of these studies is that they treat women as a homogeneous group and do not take into account that there may be more differences among women and among men, than between men and women in general. It is therefore important to understand to what degree the women joining corporate boards bring to the boardroom different values, knowledge and experiences – or if they behave the same way in the boardroom as men. I will thus present here some of the recent business case studies we have conducted in Norway on women on corporate boards.

• Understanding board diversity. Nielsen and Huse (2010a) and Huse, Nielsen and Hagen (2009) explore how board diversity impacts boards’ involvement in different tasks. The conclusion is that there is a need to go beyond the surface-level diversity, for example, insider/outsider ratio, gender, race, educational background, ownership, and so on to deep-level diversity such as real competence, personality, identity and behaviour. Women and men on boards may not be very different. Attributes other than gender may be more important (Huse, Nielsen and Hagen, 2009).

• Importance of values and perceptions. Nielsen and Huse (2010b) show how v...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- About the Contributors

- Preface

- Introduction: Gender Quotas in Management

- Part I Quota Systems in Different Cultural Settings

- Part II Conceptual Perspectives on Quota Systems

- Index