- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The frequency with which particular words are used in a text can tell us something meaningful both about that text and also about its author because their choice of words is seldom random. Focusing on the most frequent lexical items of a number of generated word frequency lists can help us to determine whether all the texts are written by the same author. Alternatively, they might wish to determine whether the most frequent words of a given text (captured by its word frequency list) are suggestive of potentially meaningful patterns that could have been overlooked had the text been read manually. This edited collection brings together cutting-edge research written by leading experts in the field on the construction of word-lists for the analysis of both frequency and keyword usage. Taken together, these papers provide a comprehensive and up-to-date survey of the most exciting research being conducted in this subject.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access What's in a Word-list? by Dawn Archer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Does Frequency Really Matter?

Words, words, words

A hypothesis popular amongst computer hackers – the infinite monkey theorem1 – holds that, given enough time, a device that produces a random sequence of letters ad infinitum will, ultimately, create not only a coherent text, but also one of great quality (for example, Shakespeare’s Hamlet). The hypothesis has become more widely known thanks to David Ives’ satirical play, Words, Words, Words (Dramatists Play Service, NY). In the play, three monkeys – Kafka, Milton and Swift – are given the task of writing something akin to Hamlet, under the watchful eye of the experiment’s designer, Dr Rosenbaum. But, as Kafka reveals when she reads aloud what she has typed thus far, the experiment is beset with seemingly insurmountable difficulties:

‘“K k k k k, k k k! K k k! K … k … k.” I don’t know! I feel like I’m repeating myself!’2

In my view, Kafka’s concern about whether the simple repetition of letters can produce a meaningful text is well placed. But I would contend that the frequency with which particular words are used in a text can tell us something meaningful about that text and also about its author(s) – especially when we compare word choice/usage against the word choice/usage of other texts (and their authors). This can be explained, albeit in a simplistic way, by inverting the underlying assumption of the infinite monkey theorem: we learn something about texts by focussing on the frequency with which authors use words precisely because their choice of words is seldom random.3

As support for my position, I offer to the reader this edited collection, which brings together a number of researchers involved in the promotion of ICT methods such as frequency and keyword analysis. Indeed, the chapters within What’s in a Word-list? Investigating Word Frequency and Keyword Extraction were originally presented at the Expert Seminar in Linguistics (Lancaster 2005). This event was hosted by the AHRC ICT Methods Network as a means of demonstrating to the Arts and Humanities disciplines the broad applicability of corpus linguistic techniques and, more specifically, frequency and keyword analysis.

Explaining frequency and keyword analysis

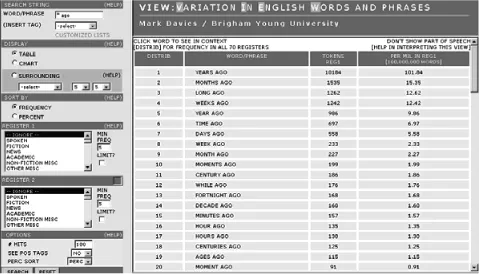

Frequency and keyword analysis involves the construction of word lists, using automatic computational techniques, which can then be analyzed in a number of ways, depending on one’s interest(s). For example, a researcher might focus on the most frequent lexical items of a number of generated word frequency lists to determine whether all the texts are written by the same author. Alternatively, they might wish to determine whether the most frequent words of a given text (captured by its word frequency list) are suggestive of potentially meaningful patterns that they might have missed had they read the text manually.4 They might then go on to view the most frequent words in their word frequency list in context (using a concordancer) as a means of determining their collocates and colligates (i.e. the content and function words with which the most frequent words keep regular company). For example, the word ‘ago’ occurs 19,326 times in the British National Corpus (BNC)5 and, according to Hoey,6 ‘is primed for collocation with year, weeks and days’. We can easily confirm this by entering the search string ‘* ago’ into Mark Davies’s relational database of the BNC. In fact, we find that nouns relating to periods of time account for the 20 most frequent collocates of ‘ago’ (see Davies, this volume, for a detailed discussion of the relational database employed here, and Scott and Tribble,7 for a more extensive discussion of the collocates of ‘ago’).

The researcher(s) who are interested in keyword analysis may also be interested in collocation and/or colligation, but they will compare, initially, the word frequency list of their chosen text (let’s call it text A) with the word frequency list of another normative or reference8 text (let’s call it text B) as a means of identifying both words that are frequent and also words that are infrequent in text A, statistically speaking, when compared to text B. This has the advantage of removing words that are common to both texts, and so allows the researcher to focus on those words that make text A distinctive from text B (and vice versa).

Figure 1.1 Results for * ago in the BNC, using VIEW

In the case of the majority of English texts, this will mean that function words (‘the’, ‘and’, ‘if’, etc.) do not occur in a generated keywords list, because function words tend to be frequent in the English language as a whole (and, as a result, are commonly found in English texts). That said, function words can occur in a keyword list if their usage is strikingly different from the norm established by the reference text. Indeed, when Culpeper9 undertook a keywords analysis of six characters from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, using the play minus the words of the character under analysis as his reference text, he found that Juliet’s most frequent keyword was actually the function word ‘if’. On inspecting the concordance lines for ‘if’ and additional keyword terms, in particular, ‘yet’, ‘would’ and ‘be’, Culpeper concluded that, when viewed as a set, they served to indicate Juliet’s elevated pensiveness, anxiety and indecision, relative to the other characters in the play.

Text mining techniques as indicators of potential relevance

As the example of Juliet (above) reveals, a set of automatically generated keywords will not necessarily match a set of human-generated keywords at first glance. In some instances, automatically generated keywords may also be found to be insignificant by the researcher in the final instance (see, for example, Archer et al., this volume), in spite of being classified as statistically significant by text analysis software. This is not as problematic as it might seem. The reason? The main utility of keywords and similar text-mining procedures is that they identify (linguistic) items which are:

1. likely to be of interest in terms of the text’s aboutness10 and structuring (that is, its genre-related and content-related characteristics); and,

2. likely to repay further study – by, for example, using a concordancer to investigate collocation, colligation, etc. (adapted from Scott, this volume).

Put simply, the contributors to this edited collection are not seeking (or wanting) to suggest that the procedures they utilize can replace human researchers. On the contrary, they offer them as a way in to texts – or, to use corpus linguistic terminology, a way of mining texts – which is time-saving and, when used sensitively, informative.

Aims, organization and content of the edited collection

The aims of What’s in a Word-list? are similar to those of the 2005 Expert Seminar, mentioned above:

• to demonstrate the benefits to be gained by engaging in corpus linguistic techniques such as frequency and keyword analysis; and,

• to demonstrate the very broad applicability of these techniques both within and outside the academic world.

These aims are especially relevant today when one considers the rate at which electronic texts are becoming available, and the recent innovations in analytic techniques which allow such data to be mined in illuminating (and relatively trouble free) ways. The contributors also identify a number of issues that are crucial, in their view, if corpus linguistic techniques are to be applied successfully within and beyond the field of linguistics. They include determining:

• what counts as a word

• what we mean by frequency

• why frequency matters so much

• the consistency of the various keyword extraction techniques

• which of the (key)words captured by keyword/word frequency lists are the most relevant (and which are not)

• whether the (de)selection of keywords introduces some level of bias

• what counts as a reference corpus and why we need one

• whether a reference corpus can be bad and still show us something

• what we gain (in real terms) by applying frequency and keyword techniques to texts.

Word frequency: use or misuse?

John Kirk begins the edited collection by (re)assessing the concept of the word (as token, type and lemmatized type), the range of words (in terms of their functions and meanings) and thus our understanding of word frequency (as a property of data). He then goes on to refer to a range of corpora – the Corpus of Dramatic Texts in Scots, the Northern Ireland Transcribed Corpus of Speech, and the Irish component of the International Corpus of English – to argue that, although word frequency appears to promise precision and objectivity, it can sometimes produce imprecision and relativity. He thus proposes that, rather than regarding word frequency as an end in itself (and something that requires no explanation), we should promote it as:

• something that needs interpretation through contextualization

• a methodology, which lends itself to approximation and replicability.

Kirk also advocates that there are some advantages to be gained by paying attention to words of low frequency as well as words of high frequency. In his concluding comments, he touches on the contribution made to linguistic theory by word frequency studies, and, in particular, the usefulness of authorship studies in the detection of plagiarism.

Word frequency, statistical stylistics and authorship attribution

David Hoover continues the discussion of high versus low frequency words, and authorship attribution, focussing specifically on some of the innovations in analytic techniques and in the ways in which word frequencies are selected for analysis. He begins with an explanation of how, historically, those working within authorship attribution and statistical stylistics have tended to base their findings on fewer than the 100 most frequent words of a corpus. These words – almost exclusively function words – are attractive because they are so frequent that they account for most of the running words of a text, and because such words have been assumed to be especially resistant to intentional manipulation by an author.11 Hoover then goes on to document the most recent work on style variation which, by concentrating on word frequency in given sections of texts rather than in the entire corpus, is proving more effective in capturing stylistic shifts. A second recent trend identified by Hoover is that of increasing the number of words analysed to as many as 6,000 most frequent words – a point at which almost all the words of the text are included, and almost all of these are content words.

The final sections of his chapter are devoted to the authorship attribution community’s renewed interest in Delta, a method for identifying differences between texts that is based on comparing how individual texts within a corpus differ from the mean for that entire corpus (following the innovative work of John Burrows). Drawing on a two million word corpus of contemporary American poetry and a much larger corpus of 46 Victorian novels, Hoover also argues that refinements in the selection of words for analysis and in alternative formulas for calculating Delta may allow for further improvements in accuracy, and result, in turn, in the establishment of a theoretical explanation of how and why word frequency analysis is able to capture authorship and style.

Word frequency in context

In Chapter 4, Mark Davies introduces some alternatives to techniques based on word searching. In particular, he foc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Series Preface

- Dedication

- 1 Does Frequency Really Matter?

- 2 Word Frequency Use or Misuse?

- 3 Word Frequency, Statistical Stylistics and Authorship Attribution

- 4 Word Frequency in Context: Alternative Architectures for Examining Related Words, Register Variation and Historical Change

- 5 Issues for Historical and Regional Corpora: First Catch Your Word

- 6 In Search of a Bad Reference Corpus

- 7 Keywords and Moral Panics:Mary Whitehouse and Media Censorship

- 8 ‘The question is, how cruel is it?’Keywords, Fox Hunting and the House of Commons

- 9 Love – ‘a familiar or a devil’? An Exploration of Key Domains in Shakespeare’s Comedies and Tragedies

- 10 Promoting the Wider Use of Word Frequency and Keyword Extraction Techniques

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2 USAS taxonomy

- Bibliography

- Index