eBook - ePub

Performing Pedagogy in Early Modern England

Gender, Instruction, and Performance

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Performing Pedagogy in Early Modern England

Gender, Instruction, and Performance

About this book

Performing Pedagogy in Early Modern England: Gender, Instruction, and Performance features essays questioning the extent to which education, an activity pursued in the home, classroom, and the church, led to, mirrored, and was perhaps even transformed by moments of instruction on stage. This volume argues that along with the popular press, the early modern stage is also a key pedagogical site and that education"performed and performative"plays a central role in gender construction. The wealth of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century printed and manuscript documents devoted to education (parenting guides, conduct books, domestic manuals, catechisms, diaries, and autobiographical writings) encourages examination of how education contributed to the formation of gendered and hierarchical structures, as well as the production, reproduction, and performance of masculinity and femininity. In examining both dramatic and non-dramatic texts via aspects of performance theory, this collection explores the ways education instilled formal academic knowledge, but also elucidates how educational practices disciplined students as members of their social realm, citizens of a nation, and representatives of their gender.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Performing Pedagogy in Early Modern England by Kathryn M. Moncrief, Kathryn R. McPherson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Literary CriticismChapter 1

“Shall I teach you to know?”: Intersections of Pedagogy, Performance, and Gender

Kathryn M. Moncrief and Kathryn R. McPherson

[T]he Elizabethan stage worked like a classroom in which the audience simultaneously experienced the subject and learned lessons about it.1

Now considering that they [young maidens] joyne allway with us in number and neareness, and sometime excede us in dignitie and calling: as they communicate with us in all qualities, and all honours even up to the scepter, so why ought they not in any wise but be made communicantes with us in education and traine, to performe that part well, which they are to play, for either equalitie with us, or sovereignty above us?”2

Pedagogy and Performance

In early modern England, attention to education on both the stage and page flourished, as Rosaline’s question, “Shall I teach you to know?” (Love’s Labor’s Lost 4.1.109) suggests. Theatrical representations of instruction augmented the formal and familial instruction English men and women received as children, students, parishioners, and subjects. Much of that instruction, occurring in the wake of both humanist and Protestant religious reforms, was guided by printed texts that explored pedagogical methods and the purpose of education for both boys and girls. The essays in this collection question the extent to which education itself, an activity rooted in study and pursued in the home, classroom, and the church, led to, mirrored, and was perhaps even transformed by moments of instruction on stage. They investigate how instructional models at work in the early modern period might be allied to the experience of hearing or acting in a play, although the upright men—mostly ministers—who served as schoolmasters during the period would certainly have recoiled in horror at this suggestion. As Richard Mulcaster’s provocative question about educating girls, “why ought not they not in any wise but be made communicantes with us in education and traine, to performe that part well, which they are to play,” suggests, education is deeply entwined with the production and performance with gender and social roles. Students, actors, teachers, and writers themselves performed their learning, just as surely as they performed aspects of their gender.

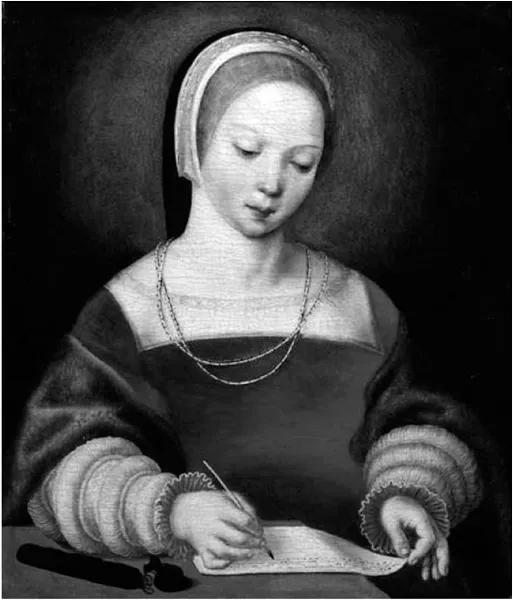

As Kenneth Charlton observes, much of the concern regarding education in the early modern period arises from “how to control the newly won freedom of ‘the priesthood of all believers.’”3 A widening of academic skills and knowledge, including reading and writing ability, spread rapidly beginning with the Reformation. But the relative democratization of learning (in the sense that it was not simply limited to the most privileged) produces, as Charlton intimates, a need to regulate how the student uses it. And because women participated in this increasing literacy, their role as readers and writers came increasingly into question. The Netherlandish portrait circa 1520, A Girl Writing (Fig. 1.1), reveals how at least one early modern family chose to present its daughter as both modestly feminine and able to read and write; the girl sits, looking modestly down, but her gaze rests on a text (perhaps a letter) she is in the process of composing. She displays both appropriate femininity and her learning, frozen at this ideal moment, in a public, permanent performance. In England, as in the Netherlands, with gender roles under scrutiny in a rapidly changing society, it comes as no surprise that educational literature, especially texts concerned with the training of girls, participates in discourses meant to direct women’s education towards approved gender roles.

Indeed, education itself served to differentiate boys and girls; as Wendy Wall argues, “Renaissance humanists … sought to gender young children through pedagogy.”4 Schooling, both formal and informal, reinforced the basic assumptions early modern English society had about the intellectual, emotional, and even spiritual differences between men and women. Education for both sexes began in the household with instruction in basic reading and perhaps writing, then proceeded to spiritual lessons via catechisms. Boys from the upper ranks began their formal education at about age seven by attending grammar school or beginning lessons with a tutor, learning Latin, grammar, rhetoric, logic, and mathematics; these boys were trained to become members of the social and political world. Girls from prosperous or gentle families remained at home to receive both domestic and religious training. Given that education in the period was “linked to morality and virtue,” Danielle Clarke argues that education “inculcated social values, acculturated the individual, and provided the learning deemed appropriate to the social status held by the pupil,” directing boys towards a vocation and girls towards a “discourse of containment.”5 For instance, humanist Juan Luis Vives, tutor to Princess Mary in the household of King Henry VIII and author of the influential Instruction of a Christen Woman (1529), saw education as a tool for restraining natural female excess and encouraging piety; his educational model was supposed to produce virtuous, eloquent men who could serve the state, and chaste women who should “study … if not for her own sake, at the least wise for her children, that she may teach them and make them good ….”6 In this view, a woman’s education had little value in terms of self-improvement; rather it served to augment her childrearing skills and to prepare her as a worthy companion for her husband. Education, for both boys and girls, produced and reinforced their gender roles. Men prepared to be leaders in social world and governors in their households; women prepared to be helpmates, mothers, and domestic managers.

Fig. 1.1 Master of the Female Half-lengths, A Girl Writing (c. 1520). NG 622. © National Gallery, London.

The wealth of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century printed and manuscript documents devoted to the subject (educational tracts, parenting guides, conduct books, domestic manuals, catechisms, diaries, and autobiographical writings) encourages examination of how education contributed to the formation of gendered and hierarchical structures, as well as the production, reproduction, and performance of masculinity and femininity.7 In this volume, however, we argue that along with the popular press, the early modern stage is also a key pedagogical site and that education—performed and performative—plays a central role in gender construction. In examining both dramatic and nondramatic texts via aspects of performance theory,8 this collection of essays explores the ways education instilled formal academic knowledge, but also elucidates how educational practices disciplined students as members of their social realm, citizens of a nation, and representatives of their gender.

Scholarly interest in the concept of performativity has grown rapidly in recent years, when interdisciplinary treatments drawing on literary theory, gender studies, and performance studies began to appear. The essays here give sustained attention to the nuances of social construction in the numerous dramatic, prescriptive, autobiographical, polemical, and literary texts they address, but their freshness lies in their understanding of pedagogy as explicitly performative and as integral to the construction of gender roles. Our consideration of performativity, particularly when applied to the gendered aspects of education so apparent in the early modern period, of course draws on the work of Judith Butler, who contends in Gender Trouble that gender must be considered “as a corporeal style, an ‘act,’ as it were, which is both intentional and performative, where ‘performative’ suggests a dramatic and contingent construction of meaning.”9 The collection also serves as a type of companion volume to our previous book of essays, Performing Maternity in Early Modern England (Ashgate, 2007) in which we argue that early modern maternity was both embodied and enacted. Like maternity, the practice of pedagogy is “repeated and public” and thus, we believe, “inherently performative.”10 Taken together, the essays in both our collections help delineate aspects of and challenges to early modern gender ideologies by examining the ways in which social identities were performed on the page and stage in early modern England.

Furthermore, the performative aspects of education arise in part from increases in numerous textual phenomena during the period. Historians concur that among the upper ranks, illiteracy among men declined rapidly after the Reformation, largely due to emphasis on the study of Scripture.11 But literacy figures for women and girls, in addition to members of the lower ranks (both men and women), remain much more nebulous.12 In any case, both the literate and illiterate were accustomed to England as a primarily oral culture, one in which reading was done aloud, catechisms were recited at least weekly, sermons were publically declaimed for the edification of the masses, and plays were performed to entertain and teach lessons, to delight and instruct. Thus, English people of all ages learned from these occasions primarily through listening and observation. As the era progressed, all these types of texts—sermons, catechisms, and plays—began to be published for private or familial reading, merging their public and performative aspects with traditional pedagogies that transmit information via the written word. Kenneth Charlton comments

Materials had to be produced whereby the flock, either by readings for themselves (a very small minority) or by having books and pamphlets read to them, could prepare themselves, or be prepared for their parental ‘vocation’.…Whatever was done in church by the clergy (or for some few in school by the schoolmaster) had, necessarily, to be reinforced by instruction at home.13

This volume argues that the potent combination of familial and religious instruction directed at and performed by people of all ages in early modern England, much of it concerned with inculcating traditional gender roles, also extended into theatres, as lessons in belief, conduct, social stratification, and gender were reinforced, and sometimes challenged and subverted, by instruction on stage.

As an instructional site, the stage gained sustained influence as the number of theatres burgeoned and popular plays were licensed for printing. In addition to the theatre’s potentially powerful pedagogical function, individual plays also show specific scenes of instruction,14 often with young women reacting to the pedagogy their teachers (often their fathers) used to instruct them. For example, the second scene of Shakespeare’s The Tempest begins with Prospero’s directions to his daughter, “Be collected” (1.2.13) and “Obey, and be attentive” (1.2.38) as he reveals to her the mystery of her background and his fallen fortunes. Throughout the scene he insists that Miranda pay close attention: “I pray thee mark me” (1.2.67), “Dost thou attend me?” (1.2.78), “Thou attend’st not!” (1.2.87), and “Dost thou hear?” (1.2.106). She responds with assurances that she is attentive— “O, good sir, I do” (1.2.88)—and that she is listening “most heedfully” (1.2.78). Their interaction—his need to convey his knowledge and have her demonstrate her understanding of it—has a decidedly pedagogical tone as he reminds her that he has used his books and their isolated environment, as a schoolmaster would, to teach her:

Sit still, and hear the last of our sea-sorrow;

Here in this island we arriv’d, and here

Have I, thy schoolmaster, made thee more profit

Than other princes can, that have more time

For vainer hours, and tutors not so careful. (1.2.171–4)

Here in this island we arriv’d, and here

Have I, thy schoolmaster, made thee more profit

Than other princes can, that have more time

For vainer hours, and tutors not so careful. (1.2.171–4)

Additionally, Prospero’s initial instructions to his daughter emphasize not only the necessity of her attention, but her acquiescence. Her strangely incurious response, however, “More to know/ Did never meddle with my thoughts” (1.2.21–2), exposes an important paradox that illustrates one facet of the gendered nature of education for...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- 1 “Shall I teach you to know?”: Intersections of Pedagogy, Performance, and Gender

- Part 1 Humanism and its Discontents

- Part 2 Manifestations of Manhood

- Part 3 Decoding Domesticity

- Part 4 Pedagogy Performed

- Selected Bibliography

- Index