![]()

1 Young people and the changing face of Christianity

Viva il Papa

Nothing could have rendered the start of 2015 more providential for the Philippines, as it has once again demonstrated the enduring vibrancy of Catholicism in the country. Pope Francis, in whom 72% of adult Filipinos have a great deal of trust, made an official apostolic visit, and his faithful did not disappoint him (SWS, 2015). From his arrival until his departure, the public mood during his four-day trip was consistently festive, a terrific showmanship of joy and force that betrays the inherent solemnity of Catholic rites. During his concluding Mass, held at the Luneta Grandstand in Manila, an unprecedented crowd of 6 million came, beating the city’s own record of the largest papal crowd of 5 million when Pope John Paul II visited in 1995 (AP, 2015).

That Manila was suffering a typhoon, a rare occurrence in January, did not seem to matter to his followers. The rain, the Mass, the Pope, and his drenched Filipinos all became a picturesque moment showcasing the continuing relevance of Catholicism in a country whose grand narrative is that of suffering under the successive regimes of Spain, the United States, Japan, martial law, and now natural disasters and poverty. Immortalising the moment are photo galleries showcasing how “the Filipino faith is waterproof” which have gone viral in social media (Bartolome, 2015).

The Pope’s tight itinerary also included a visit to the Pontifical University of Santo Tomas (UST), the oldest university in Asia. While it was mainly in keeping with the tradition of his predecessors, his visit to UST also underscored his desire to meet young people. Indeed, thousands of young people camped out the night before and braved the rain to see the Pope and participate in a liturgy that included a series of prayers, songs, Scripture reading, and testimonies from selected youth. Indicative of his endearment to youth was his moniker “Lolo Kiko,” which referred to Pope Francis as grandfather.

What made this event especially moving was when Lolo Kiko deviated from his prepared speech in response to a 12-year-old girl who, in her testimony during the program, broke down in tears as she asked, “Why does God allow children to become prostitutes?” Recognising that she was the only person who had posed this question, “for which there is no answer,” Pope Francis took the opportunity to challenge his audience to “think of St. Francis who died with empty hands and empty pockets with a full heart.” In his impromptu speech, the Pope believes that in following the example of the saint whose name he chose for himself, there will be “no young museums” and only “wise young people” (Pope Francis, 2015).

Figure 1.1 In a tweet, CNN’s report on the papal Mass in early 2015 was re-appropriated to show that “the Filipino faith is waterproof”

Source: twitter.com/PinoyQuotes/status/556818336160309248/photo/1

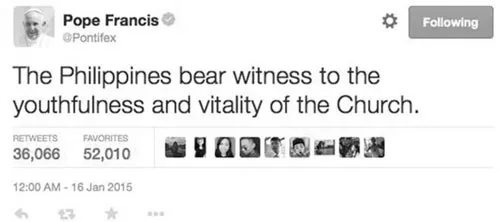

Apart from the spontaneity of the Pope, the encounter at UST also drew attention to the youthfulness of Catholicism in the Philippines. On his Twitter account, the Pope1 exclaimed that the Philippines bears “witness to the youthfulness and vitality of the Church.” Short as it is, the tweet is loaded with meaning. Followed by more than 5 million Twitter accounts around the world, it was a message meant to show that in contrast to its state in Europe, Catholicism elsewhere is not dying. Yet it also recognises that the present and future of Catholic vibrancy has moved to postcolonial societies like the Philippines. Christianity, as Jenkins (2011) and Sanneh and Carpenter (2005) have pointed out, has moved to the Global South.

Figure 1.2 Pope Francis’s tweet in the wake of his visit to the Philippines

Source: twitter.com/pontifex/status/555997950338293760

Turn to the south

Undeniably, the impression one gets is that Christianity is young and full of vitality in the Global South. Already, Christianity is making its presence felt through conversions and fast-growing movements in Latin America, Africa and Asia – areas that largely constitute the generally young societies of the Global South. The Pew Research Center (2011) reports that 61% of Christians already live in this wide region. By 2050, the projection is that only 20% of the world’s “3.2 billion Christians will be non-Hispanic whites” (Jenkins, 2011: 3). Accompanying the impression that Christianity is vibrant in the Global South is the view that it is highly pious and largely conservative in relation to the Scriptures and morality (Cornelio, 2014b). Reinforcing this general impression is the apparent liberalism of Christianity in the West, especially among Protestant denominations that have already welcomed gay bishops and women clergy (Jenkins, 2006).

However, the picture in the Global South is not entirely homogeneous. Christianity, to begin with, cannot be assumed to be solely a monolithic entity. It has a long history involving dissension and the emergence of new movements and denominations (Woodhead, 2004). While it may have monolithic features in the form of its rituals and doctrine, its spread around the world is coloured by local knowledge and practices (Whitehouse, 2006). In the contemporary period, it confronts too many issues on global and local scales that compel its movements and congregations to “remain relevant in a changing world” (Vincett and Obinna, 2014: 1). The various strands of theological thought in Asia, for example, are informed by different encounters with local spiritualities, the reality of pluralism, and specific experiences of conflict and suffering (Amaladoss, 2014). So while there are comparable experiences of suffering among Indians and Koreans, their theologies of emancipation specifically relate to local histories of internal and regional conflict.

Even within societies, Christianity cannot be assumed to be homogenous either. In the Philippines, the vibrancy that Pope Francis witnessed is equally complex.2 Based on a very recent national survey, several indicators point to the very high religiosity of Filipino Catholics (see Mangahas and Labucay, 2013). Some 78%, for example, consider themselves “somewhat” or “very” religious, and 84% attend Mass at least once a month. In terms of belief, the Philippines has consistently topped different countries in the survey administered by the International Social Science Programme (Smith, 2012). In their 2008 survey, 83.6% asserted that “I know God really exists and I have no doubts about it,” and 91.9% believed in a personal God (Smith, 2012: 7).

Coupled with media-sensationalised events such as human crucifixion during Lent and the overwhelming procession of the Black Nazarene at the start of every year, these statistical data may easily suggest both the high level of piety and the theological conservatism of Filipino Catholics (Bautista and Bräunlein, 2014). Indeed, in terms of moral views, the Philippines is also arguably conservative. A recent survey shows that among adult Filipinos, 93% deem it “unacceptable” to have an abortion, 71% to have premarital sex, and 67% to get a divorce (Pew Research Center, 2014).

At the same time, however, Catholics in Philippine society appear to undergo a transition with regard to their religious and moral attitudes. Perhaps most drastic is the decline in weekly church attendance among Catholic adults from 64% in 1991 to 37% in 2013 (Mangahas and Labucay, 2013). The controversial Reproductive Health Bill, passed into law in 2012, received the support of 71% of adult Filipino Catholics (Dalangin-Fernandez, 2008). Church leaders rejected it for various reasons, including the moral issue they have with modern family planning and reproductive health education in schools, but 51% of Filipino Catholic youth disagree with their church leaders on this issue and many others (Rufo, 2015). Some 55% of these youth also disagree with the “involvement of the Church in political issues,” which seems to be a direct affront to the long history of political participation by church leaders (Rufo, 2015).

Turn to the youth

It is in light of this complexity that Catholicism and youth in the Philippines presents itself as a worthwhile case to study. With 81% of the population professing it, Catholicism is the predominant religion in the country (NSO, 2014). In context, Philippine society is significantly young, with 40% of the population below 18 years old (NSO, 2014). Enriching our understanding of world Christianity, the young people this book examines are part of this changing religious landscape in the Philippines (Phan, 2012). It is not surprising, therefore, that their thoughts and narratives that unfold in the succeeding chapters resonate with these changes. In this sense, young people are not just signifiers of social change. They may not realise it, but they may be behind a shift that is taking place within Catholicism today.

This book draws attention to the religious identity of young Filipino Catholics today. What does it mean to be Catholic to them? In this book, several areas are probed to discern the contours of these young people’s religious identity: their personal narratives, the dimensions of their reflexive spirituality, and their moral views. In the following pages, different accounts unfold showing the complexity of youthful Catholicism in the Philippines today. For example, while many of them may not necessarily go to church for Mass on a given Sunday, they are actively involved in community activities where they find fulfilment of their spirituality. Their religious identity demonstrates their religious individualisation but in ways that do not simply replicate the experience of their counterparts in the West.

Young people and Christianity

This book locates itself primarily in the emerging literature on youth and Christianity, an important move in trying to understand the condition and possible future of the religion (Joas, 2011). As hinted at above, the condition of young Filipino Catholics exemplifies the “messiness of the lived forms of Christianity” around the world that simple theological categories like conservative or liberal will fail to capture fully (Clarke, 2014: 195; see also Cornelio, 2014b).

The book’s even wider context involves scholarship on world Christianity, which gives attention to the diverse experiences of the religion in postcolonial contexts (Sanneh, 2003). Although aware of its complexity for the laity, much of the literature has focused on matters that primarily relate to Christianity as an institution: theological distinctives (Sanneh, 2003), missionary work (Clarke, 2014), leadership (Jenkins, 2011), and even changing global organisational networks (Sanneh, 2005). In this body of scholarship, the religious situation of young people tends to be overlooked, an irony given the youthful condition of many developing countries in the Global South where Christianity is emerging (Jenkins, 2011). As Christianity continues to spread and evolve around the world, young people cannot be expected to be passive recipients of a unified set of beliefs and practices. They have their own generational contexts and influences that allow them to “create new forms of Christianity with new markers of fluency and authenticity” (Vincett et al., 2012: 282). In context, Christianity is the predominant religious affiliation of 32% of the global population, and it is considerably young with a global median age of 30 (Pew Research Center, 2012).

So how do young people fare in relation to Christianity around the world? My view is that as far as young people are concerned, there is no one grand narrative that informs the changing face of Christianity (Cornelio, 2015). While there may be dominant discourses depending on social, historical and geographic considerations, the overall picture for world Christianity is quite multifaceted. In some places such as Europe, there may be decline on some religious indicators, but there are also movements elsewhere that reshape or revitalise the Christian faith of young people. These phenomena cannot be isolated from one another in the context of globalisation (Joas, 2011). It is this complexity that makes it difficult to argue that Christianity is under the threat of secularisation on a global scale. So the task of researchers – especially those in the Global South – is to document, characterise and theorise the changes taking place within Christianity without uncritically subscribing to template narratives derived from Western experience (Berger, 1999).

Nevertheless, the bulk of scholarship on youth and Christianity points to what can be characterised as the “weakening thesis,” or the idea that the religiosity of young people is declining on various counts. These studies typically show a decline in religious affiliation and participation, a more selective approach to prescribed beliefs and moral issues, and the increased possibility of abandoning their Christian identity (Rausch, 2006). While the weakening thesis is already a well-rehearsed argument in the sociology of religion, especially in relation to intergenerational secularisation (Bruce, 2011; Voas, 2010), it is worth highlighting some recent findings. Pew’s landmark study on Millennials (born in the 1980s) in the USA shows, for example, that 26% consider themselves religiously unaffiliated (Pew Research Center, 2010). This statistic is remarkably high compared with those of other generations.

Some of these studies make careful qualifications to the weakening thesis. A more recent and nuanced survey shows that while American Millennial Catholics agree that “being Catholic is an important part of who I am” (86% Hispanic, 68% non-Hispanic), not many find the papacy “very meaningful” (41% Hispanic, 25% non-Hispanic) – an indication of a critical attitude towards Church hierarchy (D’Antonio et al., 2013: 143–144). Also, while sizeable proportions of Hispanic (62%) and non-Hispanic (41%) Millennial Catholics say the Mass is “very meaningful,” collectively only 20% of them attend on a weekly basis (D’Antonio et al., 2013: 144). In the USA, this example illustrates the condition of believing without belonging that Davie (1994) initially documented in the UK.

Interestingly, some other studies substantiate the weakening thesis by offering qualitative material. Day’s ethnographic work on youth and religion in the UK, for example, problematises Davie’s believing-without-belonging thesis. For Day (2009), young people, including those who may profess they are Christian, articulate their beliefs in terms of a sense of security and intimacy not with the divine but with their family and friends. Although others have described this faith condition as the “immanent faith” of young Christians in the postmodern world, it still draws from a discernible repertoire of beliefs and practices wh...