- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Nationalism and Architecture

About this book

Unlike regionalism in architecture, which has been widely discussed in recent years, nationalism in architecture has not been so well explored and understood. However, the most powerful collective representation of a nation is through its architecture and how that architecture engages the global arena by expressing, defining and sometimes negating a sense of nation in order to participate in the international world. Bringing together case studies from Europe, North and South America, the Middle East, Africa, Asia and Australia, this book provides a truly global exploration of the relationship between architecture and nationalism, via the themes of regionalism and representation, various national building projects, ethnic and trans-national expression, national identities and histories of nationalist architecture and the philosophies and sociological studies of nationalism. It argues that nationalism needs to be trans-national as a notion to be critically understood and the geographical scope of the proposed volume reflects the continuing relevance of the topic within current architectural scholarship as an overarching notion. The interdisciplinary essays are coherently grouped together in three thematic sections: Revisiting Nationalism, Interpreting Nationalism and Questioning Nationalism. These chapters, offer vignettes of the protean appearances of nationalism across nations, and offer a basis of developing wider knowledge and critically situated understanding of the question, beyond a singular nation's limited bounds.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nationalism and Architecture by Darren Deane,Sarah Butler, Raymond Quek in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Sources of Architectural Nationalism

Although architectural nationalism, which I will provisionally define as the design of a building according to considerations of how it represents or advances ideas of a nation, did not emerge as a widespread practice until the nineteenth century, its sources can be detected much earlier. Before ‘architecture’ and ‘nationalism’ were associated with each other, the historical development of each concept embodied a like manner of systematizing inquiry. ‘Architecture’ and ‘nationalism’ converge around the ordering of concrete particulars into an abstract whole by a centralized authority: in one case, the architect or architectural discipline; in the other, rulers or states. Architects carve beams into entablatures and, in so doing, elevate an element of building into the realm of publicly sanctioned representation. Nationalists, somewhat similarly, convert Venetians and Sicilians into Italians, refining the miscellaneous peoples of a state into the related members of a nation. Each action harmonizes its particulars through the use of sub-concepts intended to ameliorate irregularity or difference – for architecture, symmetry or ornamentation; in the case of nationalism, language or ethnic ties.

The Greek roots of the word architecture express sovereignty or domination (arche) over construction or craftsmanship (techne). In Marcus Vitruvius Pollio's De Architectura, composed during the first century B.C.E. as a Roman encapsulation of Greek usage of the term, architecture was associated with the ideas of order, arrangement and eurhythmy that establish a building's wholeness and attend to the pleasing rapport between that wholeness and its constituent parts.1 From the Renaissance onward, Vitruvian-influenced architecture in Europe came to be understood through theoretical formulae such as the classification of building types according to functions or columnar orders according to proportions. As compared to everyday building, architecture occupied a much larger temporal realm, connecting present-day needs with certainties gleaned from classical antiquity. Through treatises rich in verbal, mathematical and visual argumentation, architecture furthermore became a discipline transcendent of place, an authoritative building speech transportable and understandable over great distances. Broadly speaking, such artistically elevated and ennobled ‘architectures’ are not unique to European civilization; they have been commonplace across the globe for more than six millennia. From Mexico to China, the power, status and identity of those large, centralized states that came into existence after the agricultural revolution were expressed through defining architectural languages. Funerary temples, shrines, royal palaces, and fortifications stamped the unities and ideologies of a regime (and frequently its religious system), wherever they were constructed.

Nationalism was born amid another, much later revolution – the Industrial Age. As architecture had earlier developed to house and symbolize the large institutions of an agricultural state, so now political nationalism became a means of orchestrating the even larger and more complicated operations of modernizing societies. By the late eighteenth century, higher levels of production destabilized the agricultural countryside in Western Europe and, along with it, the lord-peasant social foundations of pre-national states. The onset of speculative science and philosophy, increased trade and production, growing cities, technological innovations such as steam power, and occupational specialization swamped the political structures of a court society that had been forged centuries earlier to manage an agrarian feudal economy. Movement between social classes became more fluid and turned the demographic substance of the state into a volatile mix demonstrated most forcefully during the French Revolution.

Nationalism may be considered a set of political efforts aimed at better adhering the industrializing state with its modernizing subjects. Because this new type of state was just forming, because those subjects themselves were transforming, nationalism was an inchoate, multi-faceted approach – using political, literary, musical, artistic, and architectural means – to press unity onto diverse peoples occupying a common political territory. As we shall see, fudging or figuring out the sources of that ‘unity’ was a preoccupation of nationalistic discourse. Did they come from within or without the nation's boundaries? Were they to be found in the remote past or could they be located in present circumstances? Did they have something to do with historic mission or were they more a matter of progress and destiny? In any event, nationalistic approaches sought to impose the substance of the sources onto works of architecture, expressive of the nation state. ‘Nationalism,’ wrote the philosopher and anthropologist Ernest Gellner, ‘is essentially the transfer of the focus of man's identity to a culture which is mediated by literacy and an extensive, formal educational system.’2 Like architecture before it, nationalism involved the dissemination of a culture gleaned from ‘prized sources’ over great distances and among diverse peoples.

In this essay, I trace the development of architectural nationalism in two prominent lands – France and Germany – from the Renaissance to the nineteenth century, as they represent the different poles of architectural nationalism. In the case of France, a centralizing state adopted a new architectural language, Renaissance classicism, which it developed over many centuries as a means of cohering the French ruler, capital, bureaucracy, built institutions and population. By contrast, German nationalism emerged before the unified German state, and veered into an expansive set of proposals as to how a national people could discover the sources for its appropriate national architecture. The French and German approaches have played a part in the subsequent development of architectural nationalism worldwide, and I will close the essay with reflections on some of those trajectories in Great Britain, the United States of America, and Israel.

The Inter-National Style of French Classicism

Following the publication of Leon Battista Alberti's De Re Aedificatoria in 1485, and following France's occupation of parts of northern Italy in the 1490s, classical architectural ideas began to take hold of the old Roman province of Gaul. By the middle of the sixteenth century, the French King Francis I considered the Italian architect Sebastiano Serlio to design his palace of the Louvre in Paris, and then settled on a French architect Pierre Lescot for what has become known as the Lescot wing (1546-1551). Lescot's turn to those same classical orders advanced by Italian architectural theorists Alberti and Serlio blossomed into French classicism over subsequent centuries, a manner of architectural production intimately tied to the centripetal dictates, first, of the French monarchy and, later, of the French nation. Well before political nationalism saw the light of day, an architectural version born out of international comparison and monarchical accumulation of power had made itself felt.

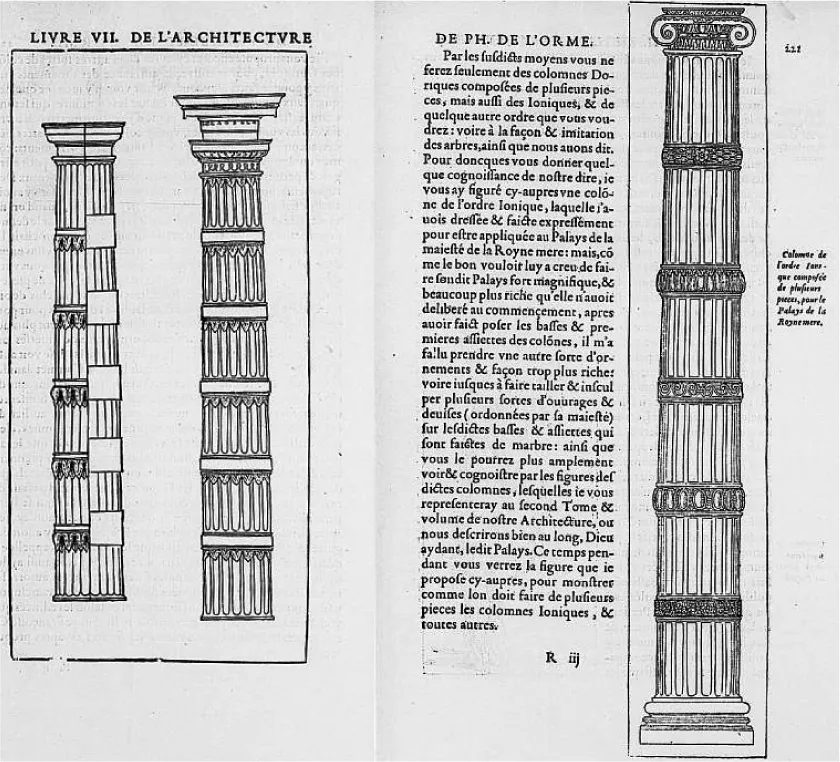

The proto-nationalistic aspect of French architectural classicism lay in the fact that the ideas and elements came from Italy, and that they were grafted onto or replaced, a robust medieval building tradition. French classicism, ostensibly a flowering of ancient Roman and contemporaneous Italian forms and ideas, was the first example within Early Modern European architectural culture of a national-type reaction. Philibert de l'Orme's The First Book of Architecture, completed in 1567, was the earliest French architectural treatise, and an expression of a desire to temper any importation of classicism through French characteristics. If other nations (ancient Greece, Rome, and now Italy) could invent architectural orders, asked Philibert, why couldn't France? Accordingly, he came up with a proposal for a French architectural order by adding banding to the shafts of each of the five Roman orders. Philibert based his idea on the fact that since French architects worked in softer stones than marble, the northern materials could not easily be cut as monolithic columns; individual drums were needed to assemble a column, and banding would cover their joints – stamping Frenchness onto the design.3

It is important to point out that architectural nationalism in this early formulation did not spring from characteristics of either the common people or the shared land. Rather, it was a matter of elites – architects, kings and state institutions coming to terms with their participation within an evolving international arena of design and positioning their involvement advantageously with respect to their own state. The classicizing discipline of architecture fit perfectly with the aims of a French monarchy seeking to disempower the built symbols of both rural nobles and urban medieval guilds.

Fig. 1 Philbert de l'Orme, Le premier tome de l'architecture (1567), French Banded Columns

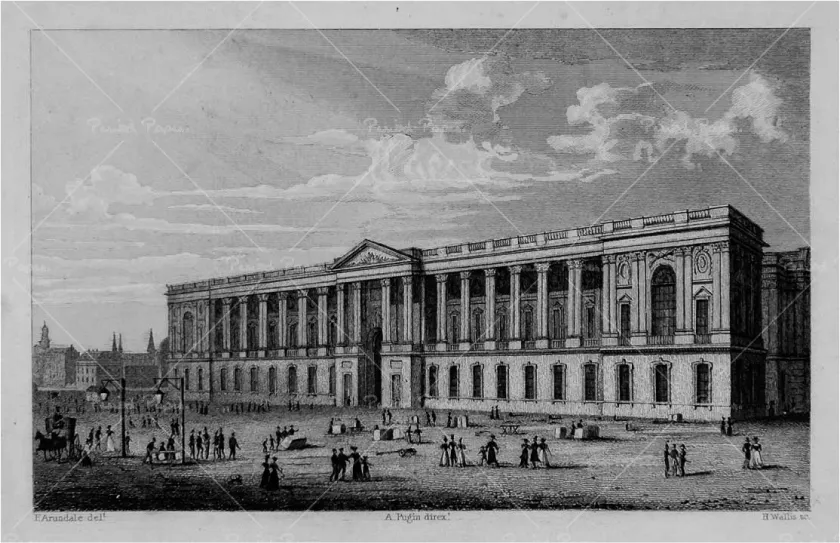

By the middle of the seventeenth century, another French architectural theorist, Claude Perrault, questioned the authority of the ancients and Italians from another vantage point. Not ostensibly advocating French building, Perrault championed French science and reason. A major advocate for the moderns in the ‘Quarrel between the Ancients and the Moderns,’ Perrault noted the contributions of Descartes, Gassendi and Malebranche to the advancement of knowledge. The authority of ancient philosophers like Aristotle (and, by implication, architects) was undermined and, along with it, commonly held assumptions that antique approaches were innately superior to their modern counterparts.4 Perrault's empirical approach led him to question formulas of ideal, invariant beauty associated with the Renaissance revival of classicism. Instead of accepting Roman and Italian models for columnar proportion, he advocated a scientific study of what had been built so far and the elimination of extremes: what amounted to a strengthening of the common middle as against an individual architect's freedom of choice and invention.5 The fact that Perrault's treatise, Ordonnance for the Five Kinds of Columns after the Methods of the Ancients appeared in 1683, twelve years after the founding of the Royal Academy of Architecture in Paris, was no accident. If proportions were relative and subject most to custom, henceforth it would be the French Academy that would promote the most correct and pleasing customs. Architectural classicism, epitomized by Perrault's design for an extension of the Louvre palace, executed between 1665 and 1680, would develop in sync with the state.

Fig. 2 Claude Perrault, Louvre facade, Paris (1670)

The Royal Academy of Architecture followed the work of other academies that began with Cardinal Richelieu's French Academy, founded in 1635 to oversee and standardize usage of the French language. Its role was to aggregate and systematize architectural teaching and design as well as investigate and develop ideas for a French columnar order and, by implication, a French manner of architecture.6 Like language, which would later become one of the bases for theories of nationalism, architecture was to be studied, purified and improved by institutions of the state. Yet unlike the French language, French architectural classicism was more akin to the Latin language, a pan-European legacy derived from classical times. At the academy, students studied the great exemplars of classical architecture from antiquity and recent times, regardless of their origins within French territory. That reservoir of formal knowledge, much of which came from Italy, became the basis for French ‘national’ design. The course of French national architecture was set in place by neither the ultimate sources of the elements nor their essential or universal characteristics, but rather the way they were orchestrated by a centralized institution – the Royal Academy of Architecture. French architectural nationalism was an a priori design system transmitted from ruler to those ruled. During what has been called the Ancien Régime, the centralization of architectural authority within the royal-sponsored academy in Paris forged a French national style that stamped a symbolic, if internationally-derived and -conscious, built unity over the breadth of the land.

By the end of the eighteenth century, political nationalism caught up with its architectural version. The French Revolution exposed the emergence of the modern nation-state as reactive to the royal state. Yet because the middle-class revolutionaries fought for a unitary and centralized French nation, they saw the value of retaining certain proto-nationalistic symbols – especially in the realm of architecture – derived from the monarchy. As historian Eric Hobsbawm tells us, during the Revolutionary Period in France the middle class citizenry looked to the idea of France, the nation, not as an outgrowth from ideas of ‘deep France,’ or the peasant countryside. Rather, France as a nation was a willed, central source of power and authority – initially, the Directorate – that could represent common traditions, aspirations and interests.7 Before nations were understood to consist of national citizens whose homogeneity could be demonstrated on the basis of language, ethnicity or other factors, they were assemblages of heterogeneous peoples held together more by negative than positive factors – for example, an opposition to the old feudal or aristocratic order of exclusionary social castes. Ernest Gellner similarly characterizes early nationalism as ‘the establishment of an anonymous, impersonal society, with mutually substitutable atomized individuals, held together above all by a shared (high) culture of this kind, in place of a previous complex structure of local groups, sustained by folk cultures reproduced locally and idiosyncratically by the micro-groups themselves.’8 No wonder that opposition to the old regime did not extend, in its archite...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Figures

- List of Contributors

- 1 The Sources of Architectural Nationalism

- 2 Religion and Nation: The Architecture and Symbolism of Irish Identity in the Post-War British Catholic Church

- 3 Exporting Architectural National Expertise: Arieh Sharon's Ife University Campus in West–Nigeria (1962-1976)

- 4 Lewis Mumford and the Quest for a Jewish Architecture

- 5 Power, Nationalism and National Representation in Modern Architecture and Exhibition Design at Expo 58

- 6 Conceptualizing National Architectures: Architectural Histories and National Ideologies among the South Slavs

- 7 William A. Scott (1871-1921) and Irish Nationalism

- 8 The Building Without a Shadow: National Identity and the International Style

- 9 The Pohjola Building: Reconciling Contradictions in Finnish Architecture Around 1900

- 10 Louis Kahn's ‘Fairy Tales’ of American Institutions

- 11 Post-Colonial Nation-Building and Symbolic Structures in South Africa

- 12 Looking-up: Nationalism and Internationalism in Ceilings, 1850-2000

- 13 Jørn Utzon's Radical Internationalism: Nordic Grounding and the Emulation of China

- 14 Constructing National Identity Through the International Style: Alvar Aalto and Finland

- 15 From Nationalist to Critical Regionalist Architecture

- 16 A Discipline Without a Country: Geert Bekaert and Universal Architecture (in Belgium)

- 17 How National is a National Canon? Questions of Heritage Construction in Swedish Architecture

- 18 Architecting the Cosmos: EXPO 2010

- 19 Architectural Koinè and Trans-National Spanish Architecture

- 20 Architecture as a Medium of Trans-National (Post)Memory

- 21 The Cloak of a Nation: Republic of China/Taiwan/Chinese Taipei, Questions for the Pursuit of Nationalism in Architecture

- Bibliography

- Digital Resources

- Index