![]()

Chapter 1

A New Imperative for the EU Transport Policy

…a new imperative – sustainable development – offers an opportunity, not to say lever, for adopting the common transport policy. (CEC 2001)

The relation between transport’s positive effects and its negative social and environmental impacts could be compared to that of Siamese twins. Not only is it difficult to separate the twins, but doing so is a highly risky business. Separation could lead to the death of both parts. Similarly, eliminating most or all of transport’s negative impacts could represent a threat to transport as we know it. Therefore, it is difficult to create a comfortable match between transport and sustainable development.

Even so, it is widely acknowledged that the increasingly devastating impacts of transport must be addressed because the overall negative impacts are beginning to exceed the overall positive ones. Therefore, business as usual is unacceptable. Making transport sustainable, however, probably represents, after the elimination of poverty, the most troubling theme of sustainable development. Sustainable transport will likely require major lifestyle changes in most developed countries – something that nobody finds easy.

Yet for decades attempts have been made to make transport sustainable by eliminating its negative impacts without too adversely affecting its positive ones. Since the beginning of the 1990s, most attempts have been of the sustainable mobility variety: the development of more efficient conventional transport technology (for example low-sulphur diesel and hybrid vehicles); the use of alternative fuels (for example bio fuels and hydrogen); the promotion of an efficient and affordable public transport system (for example buses and high-speed trains); the encouragement of environmental attitudes and awareness (for example information campaigns and environmental NGOs); and the use of sustainable land-use planning (for example densification and mixed-use development).

These attempts are so often presented as prerequisites for sustainability that they are taken for granted. But how successful are they really? To what extent do they contribute (or fail to contribute) to sustainable mobility? Why do some attempts succeed and others fail? Or more basically: How is sustainable mobility to be achieved? This book answers these questions.

The approach taken follows four rationales: First, each attempt’s appropriateness to the goal of sustainable mobility should be treated as a hypothesis rather than as a fact. Thus, each hypothesis should be subjected to thorough empirical investigations in order to determine its appropriateness. I develop six hypotheses based on a review of the sustainable mobility literature. These hypotheses are studied in a number of empirical investigations carried out between 2001 and 2004. The results from the empirical investigations are synthesised into fourteen theses on the roles of technology, public transport, green attitudes and land-use planning, which form the basis for a theory of sustainable mobility.

Second, the research design employed is an interdisciplinary one, which is appropriate given the previous dominance of an engineering- and economic-based paradigm in research on sustainable mobility (Banister et al. 2000; Black and Nijkamp 2002a; Geenhuizen et al. 2002; Rietveld and Stough 2005). Thus, I draw on evidence from empirical studies using a rich variety of qualitative and quantitative social science methodologies as well as more traditional engineering- and economic-based methodologies. The empirical data is analysed by means of relevant theoretical positions within technologically-orientated environmental studies, sociology, social psychology and planning research (that is life cycle theory, attitude theory and planning theory). I focus on passenger mobility, partly because of the need to limit the book’s scope and partly because of my professional background; the equally important challenge of achieving sustainable mobility of goods should not, however, be forgotten. Moreover, I focus on motorized passenger mobility because reducing its negative social and environmental impacts represents the main challenge in achieving sustainable mobility.

Third, attempts at achieving sustainable mobility should include leisure-time travel (including tourism), which now accounts for 50 per cent of the yearly travel distance in developed countries. Thus, I give special attention to leisure-time travel and the challenges it represents to the goal of sustainable mobility.

Fourth, the book’s main research issue relates to the challenge of achieving sustainable mobility in the EU. Thus, I draw from studies carried out in EU countries. However, I also draw from studies carried out in Norway because I regard them as highly relevant to the challenge of achieving sustainable mobility in the EU. Therefore, my findings and recommendations for policy must be considered in light of the EU’s and Norway’s geographical, cultural and socio-economic conditions. Indeed, the impact of, say, environmentally responsible attitudes and land-use characteristics on travel behaviour varies from county to country. Most of the referenced studies are carried out in the EU-15 and Norway. However, according to the European Environment Agency, passenger travel behaviour in the EU-10 is likely to eventually parallel that in the EU-15 (EEA 2006). Thus, my conclusions are relevant for the EU-25.1 In fact, as far as the substantive implications of the studies I draw on are concerned, they could be applied anywhere in the Western world. Indeed, the attempts at sustainable mobility, and the theories and perspectives they rest upon, are common to most developed countries. Furthermore, the conditions under which these attempts are applied are broadly similar in many Western countries, implying that the conclusions from the EU studies must be considered to be globally applicable to developed countries. Yet, sustainable mobility is a global challenge and therefore throughout the book the challenge of achieving sustainable mobility in both developed countries and developing countries is frequently addressed. Thus, my conclusions may turn out to be relevant for a number of developing countries as well.

From 9 to 47 km a Day in Four Decades

Travel has been part of the human experience since the migrations out of Africa millions of years ago. Peoples’ motivations for travelling have varied: to escape poverty or flee from aggressive intruders; to seek adventure; to trade. For the most part, people travelled to improve their lives. Whatever the motivation, travel in early times was uncomfortable, dangerous, and enormously time-consuming. Today, some would argue, not much has changed; travel is still uncomfortable, dangerous and enormously time-consuming. There are, however, two indisputable differences between travel then and now: in modern times there has been an extraordinary growth in mobility and a great increase in its environmental and social consequences.

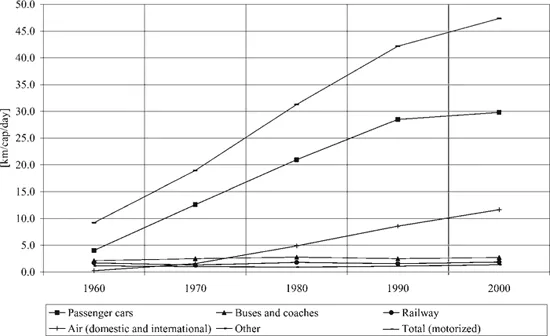

During the twentieth century the growth rates of both population and mobility were remarkable. However, whereas population growth shows signs of becoming sustainable, the growth in mobility does not (OECD 2000). While the world’s population during the previous century grew by a factor of about four, motorized passenger kilometres and tonne-kilometres by all modes each grew on average by a factor of about 100 (ibid.). In particular, the growth in mobility has been extensive during the last four decades. In 1960, Norwegians travelled an average of 9.2 km per capita daily by motorized means. By 2000 that figure had increased to 47.3 km daily (figure 1.1). A similar pattern can be found in the EU and all other OECD countries (EEA 2006; EC 2004; OECD 2000).

If the growth had resulted from increased travel by bus and train, things might not have been so alarming. Alas, more than 90 per cent of the growth in passenger travel during the last decades in Norway (and in the OECD countries) resulted from increased travel by private car and plane. This was due to the emergence of two powerful mobility phenomena during the twentieth century: the private car (and its freight counterpart, the truck) and some decades later the airplane (Black 2003). Thus, what was new during the twentieth century was not mechanized mobility but mechanized mobility by road and air (ibid.). Indeed, mobility by road and air as a modern paradigm is woven into the fabric of contemporary society (Beckmann 2002). According to the OECD this trend, that is increased travel by road and air, is likely to continue for many decades (OECD 2000).

The growth in transport indicated in figure 1.1 has been, according to the OECD, mostly positive:

It has facilitated and even stimulated just about everything regarded as progress. It has helped expand intellectual horizons and deter starvation. It has allowed efficient production and the ready distribution for widespread consumption. Comfort in travels is now commonplace, as is access to the products of distant places (OECD 2000, 13).

Figure 1.1 Motorized passenger transport in Norway, 1960–2000

Source: Høyer 2003.

Also the European Commission and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development cite increased mobility as a key factor in modern economies. However, during the last decades the costs – in terms of negative social and environmental impacts – associated with increased motorized mobility by road and air have been acknowledged. The intensity and scale of these negative impacts have escalated, and the negative impacts are now all too apparent as travel by car and airplane has increased.

The Troublesome Mobility

In fact, the idea that there are limits to the human occupation of this planet, setting aside the early prognostications of Thomas Malthus and others, has been recognized for perhaps five decades (Black and Nijkamp 2002a). Amongst the first to address environmental problems in modern times was the American biologist Rachel Carson. In her path-breaking book Silent Spring (Carson 1962) she described the ongoing disruption of wildlife and ecosystems due to man’s contamination of air, soil, and water with dangerous and even lethal materials. Furthermore, she showed that chemicals sprayed on croplands, forests, and gardens remain in the soil and eventually enter into the food chain resulting in poisoning and death. Her book became serious food for thought for politicians, bureaucrats, scientists and lay people. The problems she revealed still exist; however, their causes have changed since the early 1960s. Today, environmental problems are mostly caused by high levels of private consumption in developed countries in general and growth in motorized mobility in particular (Høyer 2000; EEA 2002: OECD 2002a). In fact, it is doubtful that any other activity impacts the environment, both locally and globally, as negatively as transport does. In addition to negative environmental impacts, transport has a number of negative social impacts that should not be taken lightly:

First, transport is a major user of energy and material resources. Roughly 20 per cent of global primary energy demand is used for transport (IEA 2004). In OECD countries 30 per cent of primary energy demand is used for transport; the corresponding figure for the EU-15 is 33 per cent. At present, transport uses mostly non-renewable energy resources, which is likely to continue for decades. Globally, consumption of energy for transport is forecast to grow at 2.1 per cent yearly, which is a higher growth rate than in any other sector (ibid.). This forecast must be considered in light of the expected growth in global car ownership. The worst case scenario (or best case for car manufacturers) suggests that over the next 20 years more cars will be made than in the entire 110-year history of the industry.2 Furthermore, production of vehicles and transport infrastructure require large amounts of materials. Such material use accounts for 20–40 per cent of the consumption of major materials: aggregates, cement, steel, and aluminium (OECD 2000).

Second, transport is a major contributor to the local, regional, and global pollution of air, soil and water. Chief among transport’s global impacts is its contribution to climate change; transport activity contributes about 20 per cent of anthropogenic CO2 worldwide and close to 30 per cent of these emissions in OECD countries (ibid.).3 Air pollution is the main local and regional impact, with major effects on human and ecosystem health. Transport is today a main source of these air pollutants (ibid.). Air pollution is expected to decline in OECD countries, although not by enough to improve air quality to WHO standards. Worldwide however, air pollution is expected to increase.

Third, transport infrastructure, mainly roads, consumes about 25–40 per cent of land in OECD urban areas and almost 10 per cent in rural areas (ibid.). Roads and railways are cutting natural and agricultural areas in ever-smaller pieces, threatening the existence of wild plants and animals.

Fourth, 1.2 million people are killed on roads yearly and up to 50 million more are injured (Peden et al. 2004). About 30 per cent of the population of the EU was exposed to urban traffic noise levels that represent a significant cause of annoyance and ill-health (OECD 2000). Some 10 per cent of the population of the EU is estimated to be seriously annoyed by aircraft noise; however, little change in the exposure to high noise levels can be expected during the next decade (ibid.).

Fifth, transport infrastructure might lead to the disruption of communities. The increasing orientation of the urban transport system toward private vehicles can have negative effects on the quality of community life. Urban motorways are sometimes built through established communities (most frequently through communities with insufficient political power to oppose such building), resulting in physical barriers within these communities.

Sixth, mobility has not been increased for everyone. On average passenger mobility has increased, but groups of people – in this book I refer to these groups as low-mobility groups – still lack access to transport. Their low access to transport reduces their access to basic public and private services and might lead to social exclusion. This is particularly the case for poor people, disabled people, elderly, women and the growing number of low-income immigrant groups in developed countries (Root et al. 2002; Tillberg 2002; Rudinger 2002; Uteng 2006).

The rather depressing situation described above characterizes an unsustainable transport system as the term is generally understood (for example, Banister 2005; Høyer 2000; Black 2003; Black and Nijkamp 2002a; Banister et al. 2000; Tengström 1999; Wegener and Greene 2002; OECD 2000; CEC 2001; WBCSD 2004).4 Without major changes in policies and practices, future transport activity could well continue the unsustainable trends of the twentieth century. According to the 2001 EU White Paper on European Transport Policy 2010 (CEC 2001), the principles of sustainable mobility should operate as guidelines for the necessary changes in policies and practices: ‘a new imperative – sustainable development – offers an opportunity, not to say lever, for adopting the common transport policy’ (ibid., 14).

The Troublesome Leisure-time Mobility

A number of complex societal conditions, or driving forces, have contributed to this unsustainable state of affairs. Amongst these forces are: globalisation, transformed lifestyles and individual travel preferences, modified demographic trends, changed household structures, increased economic growth and household incomes, increased urban sprawl, and increased specialization in education and labour. The importance of these driving forces on transport patterns and levels has been extensively investigated (Banister et al. 2000; Tengström 1999; Black 2003; Geenhuizen et al. 2002; Salomon and Mokhtarian 2002).

Closely intertwined with many of these driving forces, increased leisure-time travel represents an enormous challenge to achieving sustainable mobility. Transport research has focused on work trips and everyday travel (Banister 2005; Black 2003; Holden and Norland 2005; Geenhuizen et al. 2002; Tillberg 2002; Anable 2002; OECD 2002a; Titheridge et al. 2000); whereas leisure-time travel has been virtually unstudied. However, the relation between leisure-time travel and sustainable mobility should be given far greater emphasis. This book focuses on this relation by asking question like: Are there differences between the leisure travel of people living in the countryside and city dwellers lacking ready access to green areas? Are there different mechanisms involved when people perform their everyday travel and leisure travel, respectively? Do green individuals, characterized by a sustainable everyday travel pattern, cast aside their green at...