![]()

Part I

Theoretical conceptualization on security and development

![]()

1Criminological perspectives on African security

Ihekwoaba Declan Onwudiwe

Introduction

Although historical conflicts still characterize some of the African landscape, and have roots in colonial, political, and economic relationships, African societies are actually not faring badly in the management of their state affairs. While countries such as Angola, Somalia, Liberia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sierra Leone may have represented cases of security crises (Kenny, Serrano, and Sotomayor, 2012) in the recent past, the future of African security is not as ominous as many people believe. Most African states control their central governments, national territories, state institutions, and other domestic and external affairs. Despite some insecurity problems today, many countries in Africa do not constitute security disappointment. In an effort to address some of the myths and misconceptions and unravel some of the complexities of security issues in Africa, this chapter provides an outline of African security affairs. It furnishes a series of explanations that will help Nigeria and Africa as a whole come to terms with security concerns, and control and prevent symptoms of insecurity that confront them.

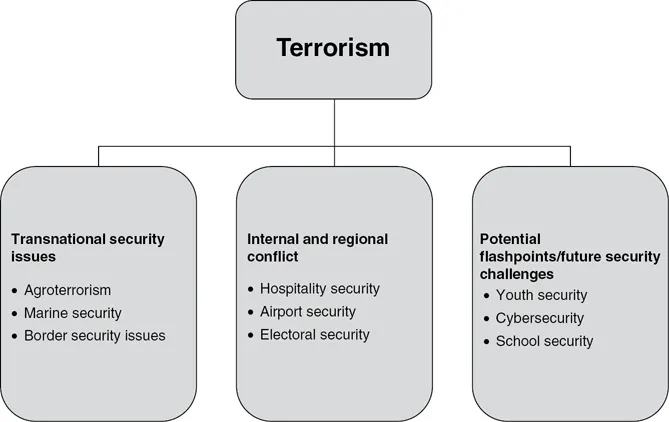

African security problems and challenges can be diagrammatically classified as in figure 1.1.

While the selection of these problems and challenges represents the obvious security matters facing the continent today, this chapter focuses largely on the issue of terrorism, pointing out, where necessary, the connections between terrorism and some of the security challenges identified above. The chapter allays the current problems and high-risk areas of terrorism, and offers counterterrorism approaches that may help to manage the situation. Noting that no nation is immune from the act of terror, it goes without saying that the safety and prevention of domestic mayhem ought to be part of the agenda of any government. In order to make the discussion broadly accessible, this chapter provides a brief outline of what constitutes terrorism; some figures and tables below help to illustrate the problem.

Definitional problems

In Globalization of Terrorism, Onwudiwe (2001) provides a historical analysis of terrorism and elaborates different definitions. He acknowledges that defining terrorism is difficult and argues that, historically, terrorism in Africa has not taken root in the way it has in other parts of the world. Crenshaw (1997) made the same analysis, by arguing that terrorism in Africa came in the form of insurgents fighting for independence against colonial occupation. It, of course, must be acknowledged and underscored that that analytical presentation may no longer apply following the tragic events of 9/11 that claimed over 3,000 lives in the United States. Since that fog of terrorism, acts of terrorism have spread along the corridors of African nations. Various regions such as the Sahel are witnessing the resurgence of terrorism. Nigeria, for example, is experiencing certain forms of political agitations in the name of terrorism. These incidents impel one to ask: if African nations are now sovereign countries, why are some of the nations in the region becoming terrorist sanctuaries? In this chapter, Nigeria will be used as a case study to demonstrate the security challenges facing Africa today, but the chapter will also examine issues of security problems in other African countries. The patterns of terrorism in Africa hamper economic development and obstruct educational advancement. The resources devoted to combat terrorism in Africa could have been allocated to address other educational, health, and infrastructural development issues.

Patterns of terrorism in Africa

Bell (1975, pp. 10–18) rightly characterized patterns and sources of terrorism in Africa as endemic. He claimed that endemic terrorism in Africa is rooted in the colonial partition of territories, which negatively divided families, tribes, and various ethnic groups for capitalist ventures. Europe underdeveloped Africa in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries without regard to African traditions and customs, traditional boundaries, regional hegemony, or tribal sentimentalities. All that mattered to the colonizers were specific areas of accumulation and control. Bell’s definition, incorporating the division of Africa and the wrecking of its economic resources, can be used to understand historical and contemporary forms of terrorism in all areas of the African continent. It must be noted that while endemic terrorism is present in sub-Saharan Africa, other issues – such as war, famine, and disease – are also troubling and are leading to the exploitation of the weak, who are mostly women and children. Due to scarce economic resources and oppressive colonial policies, some ethnic groups in Africa have opted to unify to form one autonomous community. This need for a merger has often generated conflicts. It has created deadly enemies and resulted in violence against each other as well as political revolts against European countries after World War II, which eventually led to the exit of some European countries from Africa. While some colonists retained control in South Africa and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and other areas, the hostilities they created remain today and may be regarded as sources of internal strife and divergent political agitations in various areas of the continent (Bell, 1975).

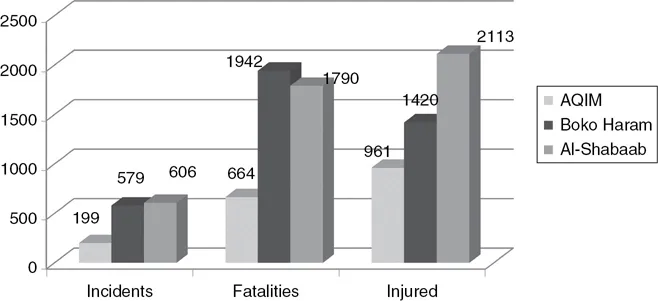

A plethora of examples demonstrate the residual effects of imperial policies in Africa on political agitations and terrorism. Ethnic cleansing by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in Uganda, religious killings in the name of Allah (God) in Nigeria, the Somalia-based terrorist group al-Shabaab, criminality and venality in many of the African countries, internal conflicts in Sudan, al-Qaeda in the Maghreb, and various other troubles constitute inimitable patterns of guerilla violence in Africa. Briefly, in Uganda, the LRA, as an opposition to the government since 1987, have enlisted children, trained them as child soldiers, and murdered thousands. Their extreme use of violence extended to the shores of southern Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and the Central African Republic, using tactics such as mass murder, mass rape, robbery, and the enslavement of children. In West Africa, the Boko Haram terror is ongoing in the northerly part of the country and has claimed about 5,000 innocent lives in 2014 (US Department of State, 2016). The violence of Boko Haram has also spread to the countries bordering Nigeria – Chad, Cameroon, and Niger. Nigeria is also experiencing deltaic violence due to the struggle for equitable allocation of oil revenue, a developmental and educational imbalance, and the pollution of the oil-producing regions. In 2014, the global society noticed the East African al-Shabaab’s mayhem against the citizens of Somalia, attacks at Mogadishu International Airport, and suicide missions in Djibouti against a French restaurant. In the Maghreb, the pattern of terrorism is shifting from Algeria to Libya. The perpetrators of these acts of terrorism are jihadist members of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) with roots in the al-Qaeda network (Botha, 2008; Global Terrorism Database, 2016). Botha (2008) insists that AQIM has a transnational ambition of spreading jihadist moralities to other regions of Africa.

From the foregoing, it can be argued that since Boko Haram and Al-Shabaab have ideologies comparable to those of AQIM, these terror networks operating in Africa must have some operational linkages. The overarching goal of these groups is to establish a caliphate in their respective regions of dominance. They all believe and agree that Western education is evil, and they propose the elimination and overthrow of national regimes that have rulers who do not adhere strictly to the Islamic doctrines. Whereas colonialism, with its own created problems in Africa, introduced Western education and religion, these cardinal practices have their own benefits. The world is ‘glocal’, and no country can survive in isolation. The education and economic development of nations are intertwined, and citizens of different countries must interact and exchange ideas to exist in a global world. Although globalization may have also created unemployment in some African countries, and even in the core nations of the world such as the United States, the poverty level of insecurity in Africa and economic marginalization of the natives cannot be used as an excuse to engage in terrorism. Nothing justifies the fog of terror that claims innocent lives (Onwudiwe, 2001). Terrorism in Africa retards economic development and prevents foreign investment that could yield dividends for the educational advancement of the African people.

Defining terrorism

In order to properly articulate counter-strategies that will be effective in controlling terrorism, it is necessary to address definitions of terrorism, as they will help in deducing the high-risk areas of terrorism in Nigeria and elsewhere in Africa. Schmid (2011) offered over 200 definitions of terrorism, noting that they are diverse and sometimes pejorative. In his view, the definition of terrorism is not universally accepted and is disputed. Other scholars and different nations and organizations have also provided divergent definitions. However, the Dictionary of Criminal Justice (see Rush, 1994, p. 333) contains four elements of what constitutes terrorism, namely: (1) the calculated use of violence to obtain political goals through instilling fear, intimidation, or coercion; (2) a climate of fear or intimidation created by means of threats or violent actions, causing sustained fear for personal safety, in order to achieve social or political goals; (3) an organized pattern of violent behaviour designed to influence government policy or intimidate the population; and (4) violent criminal behaviour designed primarily to generate fear in the community for political purposes.

From these straightforward delineations, the fourth component alone depicts a close association to security laws and regulations, and implies that the behaviour of terrorists is linked to their radical beliefs. It may be said, therefore, that a behaviour constitutes terrorism if it is rooted in political dogmas of the individual’s desire to carry out violent operations. All the four elements above also contain some judgement and contemplation of instilling fear among the citizens. Based on this definition, Rush (1994) concluded that an act is considered terrorism if there is a violent attack characterized by political intents but not necessarily designed to cause fear among the citizens.

The point to bear in mind in this analysis is that, based on their various political, social, economic, and religious paradigms, different nations face distinct threats. Thus examining different nations’ approaches to terrorism and counterterrorism also requires scrutinizing the balancing effects of surveillance and democracy, with equal attention given to the important consideration of national security matters. Simply put, the need and duty of states to provide security must not ignore the principles of civil rights in carrying out lawful and morally appropriate securitization policies.

African states, Nigeria in particular, must define terrorism in such a way that they are empowered to target those individuals who constitute present and immediate danger to the safety of their citizens. Nigeria’s definition emphasizes acts of terrorism and provides a long list of prohibited actions. Its definition is strikingly inadequate and ignores the reality that terrorism is rooted in an ideology. Without such recognition, the existing understanding cannot help one to differentiate terrorism from organized crime, gangs, and criminals, such as kidnappers and armed robbers. The Republic of South Africa passed antiterrorism legislation to keep the minority apartheid regime in power, including the well-known Terrorism Act, No. 83. As a result, these laws defined terrorism generally as an act of sabotage by anyone inciting violence against the minority regime. The government believed that freedom movement activists were communist agitators and terrorists. The various laws against terrorism were enacted to protect the apartheid regime and to arrest and prosecute individuals fighting for political liberation. One scholar concluded a few decades ago that the counterterrorism law of South Africa was promulgated as an ‘instrument of terror’ (Dugard, 1978, p. 136).

The Kenyan Terrorism Prevention Act of 2012, like the Nigerian law, fails to provide a clear definition of terrorism by not including ideology in its definition, although it comprehensively articulates what constitutes a terrorist act. According to this provision, a terrorist act includes the exercise of violence against human beings with the intent to endanger life and cause damage to property. Based on this broad definition, anyone who uses dangerous weapons and biological agents against people with the intent of disrupting national security and public safety commits an act of terrorism. The law specifically proscribes punishments for all levels and degrees of violation of the Act, including prohibition of providing financial assistance to terrorist groups and radicalization. The inclusion of radicalization in the law is significant, in that ‘a person who adopts or promotes an extreme belief system for the purpose of facilitatin...