eBook - ePub

Sustaining Cultural Development

Unified Systems and New Governance in Cultural Life

- 274 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sustaining Cultural Development

Unified Systems and New Governance in Cultural Life

About this book

In Sustaining Cultural Development, Biljana Mickov and James Doyle argue that effective programmes to promote greater participation in cultural life require substantial investment in research and strategic planning. Using studies from contributors throughout Europe, they look at ways to promote cultural life as the centre of the broader sustainable development of society. These studies illustrate how combining cultural identity, cultural diversity and creativity with increased participation of citizens in cultural life improves harmonized cultural development and promotes democracy. They indicate a shift from traditional governance of the cultural sector to a new, more horizontal, approach that links cultural workers at different levels in different sectors and different locations. This book will stimulate debate amongst cultural leaders, city managers and other policy makers, as well as serving as a resource for researchers and those teaching and learning on a range of post-graduate courses and programmes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sustaining Cultural Development by Biljana Mickov,James Doyle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art & Business. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

How We Value Arts and Culture

All across the world, the value of the arts and culture has become a pressing topic that people want to hear and talk about. And that’s interesting. It is happening not simply because the arts need to find ways to describe their value in order to attract private and public funding – they have had to do that for a long time – but rather because there has been a fundamental change in the role of the arts and culture in society. What I want to do in this presentation is to argue that we need to rethink what we mean when we use the word culture, and that we need to have a more sophisticated approach to how we value the arts and culture: one that takes into account both the several types of value that are embedded in culture and the plural perspectives and interests of different groups in society.

There was a time, about forty years ago, when the value of the arts was pretty much taken for granted and the subject did not cause too much anxiety. There was a reasonable political consensus that the arts were necessary, although they were marginal and not part of the real business of politics, which was about the economy and foreign relations.

But even back then in the twentieth century, when a spade was a spade and not a postmodern designer implement with the embedded potential to move earth; even then, we had a lot of trouble with this word ‘culture’. For a really compelling discussion of it, I would point you in the direction of the Cambridge Professor and cultural critic Raymond Williams, and his seminal book Keywords, published in 1976.

Back then, culture was principally used in two senses, and many people still think of it in this way. On the one hand it meant ‘the arts’, and ‘the arts’ were an established canon of art forms – opera, ballet, poetry, literature, painting, sculpture, music and drama. These arts each contained their own hierarchies and they were enjoyed by only a small part of society, one that was also, generally speaking, well educated and rich. This social group defined its own social standing not just through money and education, but through the very act of appreciating the arts, and thus artistic consumption and social status became synonymous, causing the arts to be labelled as elitist.

But culture also had a different meaning than the arts, an anthropological meaning that extended to include everything that we did to express and understand ourselves, from cooking to football to dancing to watching television.

These two meanings of culture led to much confusion because they were essentially oppositional. Culture in the sense of the arts and culture in the sense of popular culture were mutually exclusive: one was high, the other low; one refined, the other debased. As an individual, you could aspire to high culture, but by definition, high culture could never be adopted by the masses – if it was adopted by everyone it would no longer be high culture.

These two, essentially contradictory, notions of what culture meant led to all sorts of confusion, not least in politics where approaches to culture cut across the left/right divide. You can find the arts attacked from the left for being a middle-class pursuit, and attacked by the swashbuckling monetarists of the Reaganite and Thatcherite right for being an interference with the market. But you can also find the arts defended on the left for being one of those good things in life that everyone should have access to, and defended on the right as being a civilising and calming influence on society.

The old model of culture then is an either/or model between the arts and popular culture, but we now have to understand a new reality. And that means we’ve got to abandon these old ideas about culture existing as a set of oppositional binaries of high/low, refined/debased and elitist/popular.

The new reality demands a different way of looking at what culture means, and hence new ways of looking at the value of the arts and culture. It demands a shift in the political response to culture and it requires changes in the way that cultural funders and cultural organisations go about their business. Let me try to explain how I see this new reality.

I think that now, for practical purposes, there are three, deeply interrelated, spheres of culture: publicly funded culture, commercial culture, and homemade culture. They are not separate or oppositional, they are completely intertwined; but they are different from each other in important ways.

In publicly funded culture the state or private philanthropists (who get tax breaks) provide money to bridge the gap between what the market will provide in terms of revenue, and the cost of the cultural event or object. Here, culture is not defined through theory but by practice: what gets funded becomes culture. This pragmatic approach has allowed an expansion of what culture in this sense means, so that it can now include things like circus, puppetry and street art as well as opera and ballet. Who makes these decisions about what to fund, and hence to define this type of culture, is therefore a matter of considerable public interest. For example, official responses to the cultural production of different community, social, ethnic and faith groups carry deep significance in terms of validating or accepting different cultures within the definition of what government sees as culture. If the decisions are mainly taken by rich philanthropists or corporations you get something like the United States; if mainly by the state, then something like France.

Commercial culture is equally pragmatically defined: if someone thinks there is a chance that a song or a show will sell, it gets produced; but the consumer is the ultimate arbiter of commercial culture. Success or failure is market driven, but access to the market – the elusive ‘big bucks record deal’ that Bruce Springsteen sings about in Rosalita, the stage début, or the first novel – is controlled by a commercial mandarin class just as powerful as the bureaucrats of publicly funded culture. So in publicly funded culture and commercial culture there are gatekeepers who define the meaning of culture through their decisions.

Finally there is home-made culture, which extends from the historic objects and activities of folk art through to the postmodern punk garage band and the YouTube upload. Here, the definition of what counts as culture is much broader; it is defined by an informal self-selecting peer group and the barriers to entry are much lower. Knitting a sweater, inventing a new recipe or writing a song and posting it on Facebook might take a lot of skill, but they can be done independently without much difficulty – the decision about the quality of what is produced then lies in the hands of those who see, hear or taste the finished article.

In all three of these spheres individuals take on positions as producers and consumers, authors and readers, performers and audiences. Each of us is able to move through different roles with increasing fluidity, creating and updating our identities as we go. Artists travel freely between the funded, commercial and home-made sectors: for instance, publicly funded orchestras make commercial recordings that get sold in record shops and exchanged on filesharing websites; street fashion inspires commercial fashion; and an indie band may get a record deal and then play at a publicly funded music venue.

The rapid and enormous expansion of the internet as a space for cultural communication and as an enabler of mass creativity is credited with causing these changes, but in truth it is only one of the factors. Equally important as drivers of creative expression are the availability of cheap and good quality musical instruments and digital cameras, easy-to-use software, the building of arts infrastructure, and cultural education.

But what the internet has done – uniquely and irrevocably – is to enable people to communicate, collaborate and make money in ways that are entirely new. This has created havoc with the business models of the music, film and broadcasting sectors. It has also changed the possibilities for all three spheres of culture and all forms of cultural expression within them, presenting, across the board, a wealth of new opportunities (such as new audiences, new art forms, new distribution channels) but also a set of questions (what to do about intellectual property, investment in technology and censorship, for example).

In turn, the ability of people to create their own culture to professional standards has changed the debate about quality from being one where the arts are naturally superior to popular culture, to one where quality is debated in niches, wherever it is found. Now we have to ask, not is theatre better than TV – that makes no sense; now the question is ‘was that a good TV programme? Was that a fine performance of Othello? How do these jazz players rate?’ and so on.

So we have a situation now where the public, the commercial and the home-made have become inextricably linked and interconnected, riffing off each other and feeding off each other. We have an overall culture where these three spheres are intensely networked.

Now, does all this matter? Is this switch – from a binary model of the arts and popular culture to a triple model of funded, commercial and home-made culture – anything other than a nice theoretical exercise?

Well, as you might guess, my answer to that is very definitely yes. It is profoundly important.

Let me explain why. Under the old model funded, or high culture, could be marginalised as the elite preoccupation of a small minority, commercial culture could be dismissed as mere entertainment, and home-made culture could be patronised as being merely amateur. But put them all together and they become, in the words of Barcelona’s Head of Culture Jordi Martí i Grau, ‘the second ecosystem of humankind’. This transforms the importance of culture as a political consideration. Under the old model, politics could confine cultural policy to a very narrow field, and hence it had a very low value in the pecking-order of governments.

In the old model, popular culture could be left to its own devices. You might want to put some limits on the content of books and films and censor them, you might want to licence the playing of live music in pubs, but popular culture could more or less get on with it. As for the arts, so-called high culture, there you might want more people to have access to it because you think that’s a good thing, you might want to argue that as a matter of national status you should have a gallery and an opera house, but you would conceive of culture as something essentially peripheral, a leisure pursuit and an ornament to society, something to be afforded and indulged in once the hard business of the day was done.

But under the new model of culture that I have been talking about, cultural policy can no longer be confined to a small budget line and a narrow set of questions about art. On the contrary: if we understand culture in the terms that I have outlined – as a networked activity where funded, home-made and commercial culture are deeply interconnected – then we can start to appreciate the wider value of culture in and to society.

Let me give you three examples. The first relates to the economy. Creative work, brain work, added value from design and from cultural production are increasingly important features of successful economies. Indeed it is this part of the economy that has shown the most rapid growth over the last 20 years across the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). In London, for example, the creative economy is now equal in size to the financial services industries and employs just as many people, something that 20 years ago would have been unthinkable. In fact, these are old figures, and given the turmoil in the financial industries it’s likely that the creative and cultural economy is now relatively even more significant.

This strikingly successful performance in things like film, fashion and music has created enormous prosperity and huge economic spin-offs. Significantly, the areas of the economy that appear to be weathering the credit crunch best are related to the cultural and creative industries. Try getting a ticket to the National Theatre in London, try booking a good restaurant. Tourism is holding up. So, even looked at and valued from just this economic perspective, culture has become much more important both in its own right and also across a much broader economic canvas.

The second example of where culture has become much more important is in foreign relations. Mass tourism, 24-hour news, cheap flights, internet news and citizen journalism have combined to shrink the world. We are all having much more interaction with and exposure to other people and other nations. We encounter difference at every turn and what happens on the streets of New York one minute can lead to riots in Islamabad the next. In these circumstances we understand each other, and misunderstand each other as well, through the medium of culture. Which is why, for example, the way that a museum deals with objects from another country, or the fact that Israeli and Palestinian musicians can play together, or the way that Ancient Persians are portrayed in a Hollywood film, can become significant way beyond questions of aesthetics or artistic quality.

The third example of the increasing importance of culture is in relation to identity, where we now define ourselves not so much by our jobs – because those come and go – and not so much by our geography – because we commute and move around – but by our cultural consumption and production. I am who I am and you are who you are because of what we watch, read, listen to, write and play.

In all these three examples – the economy, foreign relations and identity formation – culture has moved from being something at the side-lines to something at the centre. That profoundly changes how we should value culture, and how we should judge the significance of culture. It also makes cultural policy a lot more complicated. For instance, whereas giving a 13-year-old schoolchild the opportunity to visit a museum might once have been a nice-to-have experience that brought a civilising influence to bear on a young mind, now a visit to a museum is an essential part of plugging that young person into the network of tripartite culture. And that will affect that young person’s job prospects, their ability to operate in a globalised world and their sense of their individual and communal identity.

And just as cultural policy is now interconnected with wider issues, so too do those wider issues affect what happens in culture. For instance, we need to be thinking about how visa policies affect visiting artists and hence international relations, and how planning policies act to create or destroy the growth of creative industries. Above all, we need to think about how educational policy can release the creative talents of everyone and not just those destined for careers in the arts.

Cultural policy interventions then are becoming much more complicated because they need to happen in all sorts of places right across this mix of funded, commercial and home-made culture, and indeed beyond.

I think it’s essential that we understand how culture works, what it means and in particular what it means to different people before we think about how culture is valued. Because the value of culture and how you describe that value and measure it differs depending on who you are.

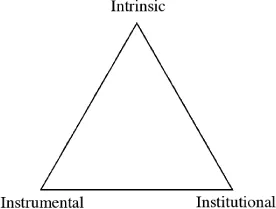

I have in the past put forward a simple triangle to try to articulate the different values that culture can have to different groups in society.

Figure 1.1 Types of cultural value

Put briefly, the argument is this: that you can look at the value of culture in three ways, using different sorts of language in each case. These three viewpoints are not mutually exclusive – on the contrary, they are complementary – but depending on who you are, they are more, or less, important.

Let me explain. At the top of the triangle is intrinsic value. Intrinsic means integral to, or an essential part of. So this implies that museums, dance, theatre and so on have a value unique to themselves. In particular I have argued that intrinsic value establishes the arts as a public good in their own right and that we should value dance because it is dance and poetry because it is poetry, and not just for other reasons, such as their economic and social impact.

But intrinsic value is also used to describe the way that art forms have individual, subjective effects on each of us. Intrinsic value is what people are talking about when they say ‘I love to dance’ or ‘that painting’s rubbish’ or ‘I need to write poems to express myself’.

Now, intrinsic value is notoriously difficult to describe, let alone measure, and the rational econometrics of government simply can’t cope with it because this aspect of culture deals in abstract concepts like fun, beauty and the sublime. It affects our emotions individually and differently, and it involves making judgements about quality. It really doesn’t fit with the hard-headed machismo that is supposed to dominate in business, politics, sport and the media. These days, if you can’t count it, it doesn’t count, and how do you put a number on something like Olafur Eliasson’s Weather Project at Tate Modern?

But to me, or to you, as an individual, it is our subjective response to culture that really matters. When I sit in a darkened auditorium listening to, say, Benjamin Britten, my feelings are awakened and I think ‘this is lovely, it’s amazing, it’s astonishing.’ I don’t sit there thinking ‘I’m so glad this performance is driving business prosperity and helping to meet tourism targets.’

So if we are talking about the value of culture to individuals, we need to talk about quality, excellence, physical and intellectual access and audience demographics. We need to take qualitative factors into account – to argue about what is good and bad art, what excellence consists of and how audience experiences can be improved.

It’s important to realise that when we are talking about intrinsic value we are using value as an active verb. I value something, you value something, they value something. And that process of valuation is subjective. You can tell me that a painting is good and try to explain why you think it is. You can give me the statistics that show that dancing will benefit me in all sorts of ways from making me healthier to making me happier. But only I can value the painting or the dance. This, I think, is a crucial point.

Because when we turn to the second type of value, instrumental value, we are dealing with an objective concept, so here we have to think about value differently. Instrumental value is used to describe instances where culture is used as a tool or instrument to accomplish some other aim – such as economic regeneration, or improved exam results, or better patient recovery times. These are the knock-on effects of culture looking to achieve things that could be achieved in other ways as well. This type of value has been of tremendous interest to politicians and funders over the last thirty years or so and at ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- About the Editors

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 How We Value Arts and Culture

- Chapter 2 Barcelona’s Cultural Policies Behind the Scenes: New Context, Renewed Strategies

- Chapter 3 Agenda 21 for Culture

- Chapter 4 If Agenda 21 for Culture is the Answer, What Was the Question?

- Chapter 5 Cultural Policies, Human Development and Institutional Innovation: or Why We Need Agenda 21 for Culture

- Chapter 6 The City of 2030

- Chapter 7 Luxembourg and The Great Region: A Cultural Challenge

- Chapter 8 The City of Bologna – A City of Culture

- Chapter 9 The Possibilities of Cultural Policies

- Chapter 10 Cork, Culture and Identity – A City Finding its Voice

- Chapter 11 To Experience and Create

- Chapter 12 Design: From Making Things to Designing the Future

- Chapter 13 City Museum and Urban Development

- Chapter 14 Museums and Globalisation

- Chapter 15 New Challenges for Museum Exhibitions

- Chapter 16 The Visitor Appears

- Chapter 17 Art, Education and the Role of the Cultural Institution

- Chapter 18 Art Education Practice

- Chapter 19 Marketing Cultural Services for the Public Sector

- Chapter 20 Creative Industries

- Chapter 21 Measure for Measure

- Chapter 22 Eindhoven – A City as a Laboratory

- Afterword

- Resources and Bibliography

- Index