eBook - ePub

The Housing Question

Tensions, Continuities, and Contingencies in the Modern City

- 322 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Housing Question

Tensions, Continuities, and Contingencies in the Modern City

About this book

In the wake of the Great Recession, housing and its financing suddenly re-emerged as questions of significant public concern. Yet both public and academic debates about housing have remained constricted, tending not to explore how the evolution of housing simultaneously entails basic forms of socio-spatial reproduction and underlying tensions in the political order. Drawing on cutting edge perspectives from urban studies, this book grants renewed, interdisciplinary energy to the housing question. It explores how housing raises a series of vexing issues surrounding rights, identity, and justice in the modern city. Through finely detailed studies that illuminate national and regional particularities- ranging from analyses of urban planning in the Soviet Union, the post-Katrina reconstruction of New Orleans, to squatting in contemporary Lima - the volume underscores how housing questions matter in a wide range of contexts. It draws attention to ruptures and continuities between high modernist and neoliberal forms of urbanism, demonstrating how housing and the dilemmas surrounding it are central to governance and the production of space in a rapidly urbanizing world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Housing Question by Edward Murphy,Najib B. Hourani in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Residential Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Putting High Modernist Planning in its Place

Chapter 1

Modernity Unbound: Tol’iatti as the New Soviet City Par Exellence

Modernity has had to bear a lot of work over the years. In this chapter I use the concept in two related senses: as it figures in international architectural history and as it was applied for much of the Soviet period within the USSR itself. It is crucial to keep in mind both usages in order to understand how Soviet architects and town planners could be among the chief beneficiaries of the increasing identification of the USSR as a modern society. For, operating in the name of a Socialist modernity that they identified as an extension of the most progressive features of international modernism, the architects, engineers, and urban planners who designed new Soviet cities in the 1960s and ’70s occupied a powerful technocratic and transnational space. They used this discursive space to redefine urban physical spaces within the USSR, particularly, though not exclusively, in new cities. The failings of the First and Third World versions of international architectural modernism have been attributed to excessive (or “high”) modernism; those of its Soviet socialist application were not, as some would argue, the result of insufficient modernism, but rather insufficient socialism.

What, though, did modernity look like in the Soviet and more broadly the socialist Second World context? What was its materialization? If, as John Urry (2005: 25) has written, the automobile was the “quintessential manufactured object produced … within 20th-century capitalism,” then my candidate for the state socialist Second World equivalent would be the large, prefabricated ferro-concrete panels, the characteristic building material of apartments from the late 1950s onward, in cities not only in the USSR but all across state socialist space. Standardized ferro-concrete panels—the Russian word, tipizatsiia conveys the process of determining the sizes and shapes to be used—became the demotic mode, the vernacular, of Soviet and East European domestic architecture, whether in Bucharest or Bishkek, Timisoara or Tol’iatti.

Tol’iatti, a city in the middle Volga region 800 kilometers (500 miles) to the southeast of Moscow, exhibits two cardinal features of Soviet town planning dating from the 1960s. First, nowhere else, at least in the USSR, did ferro-concrete apartment buildings assume such prominence and nowhere else was a brand new city of ferro-concrete apartments built on such a scale as in Tol’iatti. Tol’iatti in other words got closer than any other Soviet city to realizing the aspiration of building a modern rationalized society with homogenized, standardized social institutions and patterns of daily life.1 A second related feature of Tol’iatti’s cityscape was the mikroraion (micro-district), essentially an autonomous, self-enclosed unit of apartments, stores, schools, playgrounds and the like—an approach to urban planning that, like ferro-concrete panels, typified the Khrushchev and especially the Brezhnev eras. Not long ago, Stephen Kotkin (2007: 520) noted that along with “cheap track suits worn by seemingly every male in Uzbekistan or Bulgaria, Ukraine or Mongolia,” and “children’s playgrounds—all made at the same factories, to uniform codes, … apartment buildings (outside and inside), schools, indeed entire cities” were sufficiently identical that “studying the urban design and construction of tiny Albania can allow one to generalize about more than one-sixth of the earth’s surface.”2 Such was the appeal of the ferro-concrete panels of the mikroraion that this is only a slight exaggeration.

Tol’iatti had the distinction of being a new town not once but three times. First, thanks to the construction of a massive hydroelectric dam in the early 1950s, it was relocated some 20 miles upstream and expanded to accommodate new petrochemical industries and a significantly larger population (Prokhorenko 1966).3 Then, in 1964, the town that up to that time had been known as Stavropol was renamed in honor of the recently deceased Italian Communist Party leader, Palmiro Togliatti. To be sure only a nominal change, this second rebirth nonetheless served to further detach the city from its eighteenth-century Christian origins. Finally, in 1966, the Council of Ministers of the USSR chose the city as the site for a new car plant, the Volga Automobile Factory (VAZ), courtesy of the Italian firm, Fiat. Needing to accommodate a workforce that would number in excess of 100,000 by the mid-1970s, the city added an entirely new district, Avtograd (auto-town), that more than doubled its pre-existing size and population.

The building of Avtograd—essentially a newer version of Tol’iatti—was characteristically Soviet in that, as noted by an official from the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, the USSR outpaced the rest of the world in building new towns (Underhill 1976: 8).4 A 1967 retrospective survey of town planning in the USSR cited a figure of 900 or so founded between 1926 and 1966, of which about a third could truly claim to be novostroiki, that is, built from scratch rather than as an extension or satellite of a pre-existing settlement (Posokhin 1967: 317). Of them, several were not just new towns, but “ideal Communist cities,” as described by a group of Moscow architects in a book by that name originally published in Russian in the late 1950s (Baburov and Gutnov 1971: 7).5 Also known as “model cities” (goroda-etalon) and initially as “socialist cities” (sotsgoroda), they included Zaporozh’e (Zaporizhzhe), Magnitogorsk, the original Avtograd which later became a suburb of Nizhni-Novgorod, Bratsk, Zelenograd, Tol’iatti and, a few years later, Naberezhnye Chelny.6 Like other once-upon-a-time “ideal Communist cities,” Tol’iatti garnered aspirations to transform raw rural recruits into model urban residents and to serve as an outpost of the future Communist society.7

But one might question the extent to which Tol’iatti was a specifically Soviet or communist-inspired city. Its transformational function mimicked that of Brasília, the subject of James Holston’s much celebrated book (1989) and the prime example of what James Scott has termed “the high-modernist city” (Scott 1998). For Holston, Brasília’s “design and construction were intended as means to create [“the New Age of Brazil”] by transforming Brazilian society” (Holston 1989: 3). In Scott’s dyspeptic analysis, Brazil’s president Juscelino Kubitschek intended to use “the building of Brasília … to transform Brazil, in order to transform the candangos [people “without qualities, without culture, vagabond[s], lower-class, lowbrow”] into the proletarian heroes of the new nation” (Scott 1998: 129).

As for living in the new Tol’iatti, prospective residents could look forward to conditions rarely if anywhere experienced in the USSR, and this too resembled the conception of Brasília “as a city of the future, a city of development” that “made no reference to the habits, traditions, and practices of Brazil’s past or of its great cities” (Scott 1998: 119). In a Soviet novel published in 1979 and dedicated to the building of the new Tol’iatti (Astakhov 1979), one of the characters emphasized the future city’s fulfillment of personal and familial as distinct from collective needs. He described it as a model city (gorod-etalon), a term he defined as follows:

Very simply, it’s a city where people will live comfortably and happily, where there will be no crowding—neither on the streets, nor in apartments, nor in the stores. And it will be beautiful—everywhere. It will be a city in which one can go by foot from one end to the other in an hour and do everything a person normally does: earn a living, pick up the kids from kindergarten, get a ticket to the sports palace or the cinema, have a look at the polyclinic, call on one’s mother-in-law, rest in a prophylactorium, make necessary purchases, order a table in a restaurant for Saturday, go on a yacht, swim in a pool, take a new novel off the shelves of the library … This is not some pipe dream but an iron-clad reality of engineering. (Astakhov 1979: 23, 36)

Or at least of town planning. Erstwhile Sovietologists might have pointed out that not many Soviet citizens “normally” got to “go on a yacht” or even “have a look at the polyclinic.” But more to the point is that the model offered here as the future “iron-clad reality” (courtesy of engineering) is in the form of a narrative of leisurely diversions and personal/familial consumption.

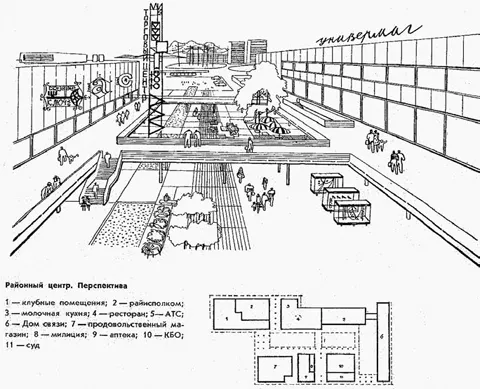

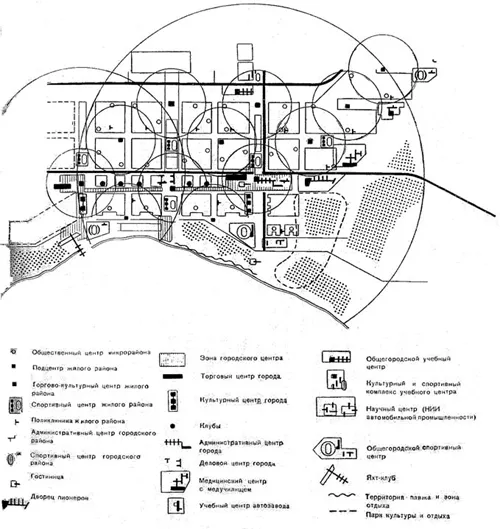

So, let’s take a look at the plan developed by a team of architects and engineers from the housing and town planning divisions of the Central Scientific Research and Design Institute under the direction of Boris Rubanenko and Viacheslav Shkvarikov. This too is a narrative of sorts, a narrative less about the heroism of building a city or the pleasure of partaking of its amenities than about the rationality, efficiency, and above all, modernity of the architects’ design (Rubanenko et al. 1968).8 Soviet authorities found it difficult if not impossible to acknowledge any resemblance between bourgeois and socialist modernity, but architectural principles were another matter. The plan, accompanied by line drawings and models characteristic of the period in which they were produced, called for a town stretching from east to west in parallel strips or zones beginning at the shoreline of the artificial sea and proceeding through park land, a residential zone, and an industrial zone containing the VAZ complex. Broad boulevards, some as wide as 600 meters, would separate the residential from industrial zones and carry traffic—mostly buses—efficiently and safely to and from the factory entrance. The entire new town would be bounded by a green zone several kilometers wide, separating it from the former new town (renamed the Central District because of its location between Avtograd and the remnants of old Stavropol). It would be subdivided into micro-districts and configured according to a recursive system of services differentiated according to frequency of use, and laid out according to strictly geometric patterns. The main construction material would consist of prefabricated large-panel components. Every feature of this plan—from its districts and micro-districts that in the words of a leading French urban sociologist “permitted the application of a very rigid grid of public facilities,” to its linearity and grandiosity—reflected the latest trends in Soviet architectural thinking (Merlin 1991: 96).9 Not for nothing was Rubanenko’s and Shkvarikov’s team awarded a national prize for their efforts, and their general scheme made “mandatory course material for generations of architecture students in the USSR and the GDR,” according to architectural historian Elke Beyer (2011: 115, 132).

Figure 1.1 Detail from Shkvarikov and Rubanenko’s General Plan, 1968

Source: Togliatti City Archive.

The praise lavished on Tol’iatti’s Avtograd signified to architecture critic Aleksandr Vysokovskii (1995: 10) that it belonged “in the premiere class of Soviet architecture.” It also signified something else—that the time of international modernism in Soviet urban architecture had arrived. Like the heroic Communist narrative, this could be rendered in diachronic terms as a chain extending from Moscow’s avant-gardist technical studios (VKhUTEMAS) and the Bauhaus in the 1920s, through Le Corbusier’s Athens Charter of 1933 and back to Soviet new town planners of the 1960s, with some “points of contiguity” along the way, such as the application of CIAM’s (the Congrès Internationale d’Architecture modern) modernism to Brasília, the Punjabi city of Chandigarh, and other major Corbusier-influenced new towns of the postwar era (Kogan 1967: 39–43, Osterman 1967: 30, Kazarinova and Romm 1968: 39–43, Barkhin 1974: 176).10 Unlike the heroic Communist narrative, it was explicitly and unapologetically transnational.

How, given repeated assertions of systemic difference and incompatibility, was such explicit acknowledgment of indebtedness to bourgeois architects and town planners possible? Convergence theory, which emerged among western social scientists during the 1960s, can provide some insight, for one of the things that impressed Pitrim Sorokin (1960), Marion Levy (1966), John Kenneth Galbraith (1967), Alfred G. Meyer (1970), and other proponents was the rise of a new technocratic elite and the increased reliance within “mature industrial society” on pragmatic and scientific methods to solve social issues or “tasks.” To be sure, Soviet commentators repeatedly rejected the notion of systemic convergence, although they did concede that technologies and administrative structures (“of production”) were transferable (Kelly 1973). This concession was not insignificant. Indeed, it—the relative autonomy of the technical—underpinned much of what was propagated at the time as the “scientific-technological revolution.”11 Just as VAZ’s “hyperfactory” would represent the latest word in integrated production based on the adoption of Fiat auto-technology, so Tol’iatti’s Avtograd would exemplify the best principles of urban planning, wherever their inspiration came from.12 Ideologists regarded both projects as essentially technical.

The emphasis among architects like Rubinenko and Skvarikov on geometric abstraction facilitated such an interpretation. It also enabled them to earn the USSR international plaudits just as other white collar workers in other fields—nuclear physicists, ballistics experts, obstetricians pursuing their psycho-prophylactic method of pain relief, biologists after the fall of Trofim Lysenko, the designers of products rapidly filling up Soviet apartments, members of dance companies, Olympic gymnastic squads, and other elite teams– did by applying techniques to improve their performance or that of the materials with which they worked. Whether one should go so far as many convergence theorists did to interpret their increasing prominence as evidence of the growing power of the Soviet “technostructure” is another matter. “Latitude” or, as already suggested, professional autonomy, seems more appropriate. Even if their work had profound effects on the Soviet public, helping to redefine the “Soviet way of life,” they could be interpreted as providing “only” technical services and it was on this basis that their expertise was permitted to rule.13 Within these discursive limits, the power of the urban technocrats was considerable. Nobody, in fact, was more powerful than they in shaping the Soviet Union’s massive urbanization project during the 1960s and ’70s.

Figure 1.2 Detail from Shkvarikov and Rubanenko’s General Plan, 1968

Source: Togliatti City Archive.

Convergence theorists’ projections of the two vectors meeting at some not-so-distant point proved illusory. While the Soviet vector would continue along the modernist-industrial path, western capitalism was about to veer off in another direction, away from Fordism and toward more “disorganized” technologies resulting in time-space compression (Lash and Urry 1987, Harvey 1990, Maier 2000). In the meantime, the French Marxist social geographer Henri Lefebvre propounded another version of convergence, arguing that in terms of conceptions of space, it had essentially already occurred in the 1920s. Whether in the Communist East or the capitalist West, the principles governing the “production of space” were the same: “technicist, scientific, and intellectualized.” Even though the approach pioneered by the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier “was looked upon at the time as both rational and revolutionary … it was tailor-made for the state—whether of the state-capitalist or the state-socialist variety”—and essentially repeated a yearning for taming social disorder as old as the Spanish colonialists in the Americas. Its characteristic feature—the fracturing of space via “the cult of rectitude in the sense of right angles and straight lines”—represented a fair description of the new Tol’iatti (Lefebve 1991: 43, 53–55, 124, 303–308).14

If, as I have been arguing, Tol’iatti represented the apogee of such thinking, what are the larger implications? Although the historiography of the post-Stalin decades is not extensive, I have noticed a tendency to distinguish the sixties from subsequent decades. If the sixties represented “promise,” the seventies and eighties represent the sixties’ unfulfillment. Perhaps this interpretative framework originated already in the 1980s with Petr Vail and Aleksandr Genis’ highly influential book on the “World of the Soviet Man” (Vail and Ginis 1988). Or maybe it seeped into scholars’ consciousness by analogy with what the sixties have meant in the West, to wit, “the sixties are no more, long live the sixties!”

But there are two reasons why the application to the USSR of such a notion would be misleading. First, in political terms, the Soviet sixties came to an end well before the decade did. With Khrushchev’s ouster in October 1964, the “men of the sixties” (shestidesiatniki) whom he had cultivated (or at least tolerated), found themselves marginalized, and while some claim that it wasn’t until Soviet tanks entered Prague in August 1968 that the intelligentsia irrevocably lost its illusions about being able to influence political authorities, the influence they may have exercised previously was not great.15 Second, in other respects, the big changes either came earlier—during the “Thaw” of the 1950s and early 1960s—or, as I have been arguing, continued to develop well after the end of the sixties (Bittner 2008, Dobson 2009, Ilic and Smith 2009). In drawing up their general plan for T...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Housing Questions Past, Present, and Future

- Part I Putting High Modernist Planning in its Place

- Part II The State of Uneven Geographic Developments

- Part III Spaces of Home in the City of Rights

- Part IV Final Reflections

- Bibliography

- Index