![]()

1

Displaced in the Sun

Landscape—that, in fact, is what Paris becomes for the flâneur. Or, more precisely: the city splits for him into its dialectical poles. It opens up to him as a landscape, even as it closes around him as a room.1

There is an outside and an inside, and myself in the middle, this is perhaps what I am, the thing that divides the world in two, on one side the outside, on the other the inside, it can be thin like a blade, I am neither on one side nor on the other, I am in the middle, I am the wall, I have two faces [surfaces] and no depth.2

Before architecture, before the scourge of a populace, the landscape, or more specifically, the ground itself, functioned as an unyielding constant for the making of colonial histories. With the horizon, as both line and marker, individuals were bound to the landscape. While the first marks of human occupation were those that simultaneously registered the specificity of a location, such recordings also ensured the boundaries of it. The ground, functioning as both a physical entity as well as a metaphoric medium, effected the composition of these histories via exploration and occupation. Having situated oneself in the landscape, the potential of custodial license was measured. As Walter Benjamin infers, that which follows the landscape—the city may also enclose oneself in a room within which knowledge is collected and then dispersed. One need not a room to provide shelter, but draw themselves within an ever-evolving map of their own making, thus ensuring a coalescence of the landscape, vision and the body.

Apart from its connotations of the picturesque and empirical framing, the colonial landscape was maintained as a defining framework for the wielding of power the agency of the map as a longstanding arbiter of topologies governed persons and the environment. Once topographic contours and destinations are transposed onto a two-dimensional plane, the asymptoptic lines that connote a person’s apprehension of a place also signify a kind of ownership. Valerio Toccafondi describes the formation of early Italian colonial maps in East Africa as functioning within a number of registers: “A truthful graphic representation of the ground [terreno] constitutes the fundamental element for any successive planning, this military campaign is like an economical plan of development or, more simply, a rational administrative displacement [dislocazione].”3

Between these graphic indicators are multiple scales, grounds. And one’s knowledge of these hidden geographies yields narratives of spaces public and private, seen and invisible. “Once knowledge can be analyzed in terms of region, domain, implantation, displacement, transposition,” Michel Foucault contends, “one is able to capture the process by which knowledge functions as a form of power and disseminates the effects of power.”4 What happened to the description and composition of the East African landscape when it became a condition of an Italian colonial spatial history is the focus of this chapter. Beyond broad reaches of land and its borders, there also exists a landscape that has yet to be fully mapped graphically and textually. From 1888 until 1941, a number of personal narratives witness the evolution of la colonia primogenita, Italy’s “first born” colony. The map intersected with the physical construction of Asmara, conveying the furthermost edges of the modern colonial city. From its first conception as a proving ground for the Italian military protecting commercial interests to a burgeoning center for mercantile and political exchange, Asmara was built first among the written narratives by visiting Europeans. This chapter asks how the ground of Eritrea and the city of Asmara were mapped and visually mastered within these narratives.

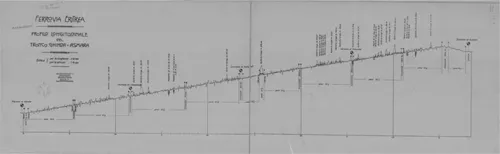

1.1 Ferrovia Eritrea: Longitudinal section of coastal Eritrea from Massawa (Taulud) to Ghinda (Asmara, 1914)

Commencing with some of the earliest written descriptions of the region, the chapter unfolds as a (dis)continuous set of travelogues across the varied, and often harsh, physical and psychic geographies of the colony. Rather than commencing with the first known travelers’ journal entries from the late sixteenth century, the chapter narrows the scope of investigation to those writings that began shortly before the founding of the Italian colony.5 It seeks to identify the originary modern spaces of the colony that endured among rhetorical postures made by successive colonial administrations. These narratives at once signify the inscription of an Italian colonial atmosphere [atmosfera] and character [carattere] in Asmara. Jointly defined as that which constitutes italianità or Italian-ness, these literary tropes aid in competing definitions of the modern colonial city. To move beyond their formal linguistic derivation is important as such notions fall within that which Edward Said calls “imaginative geographies.”6 These terms became the benchmark for both colonial architects and subjects alike in Asmara. For some, these became the derivations of Italy’s posto al sole or “a place in the sun.” The deployment of an “Italian atmosphere” and an “Italian character” among the early narratives transformed the meaning and form of colonial urbanism over time across diverse representations.

1.2 Postcard; View of piazza in Massaua (Massawa), Eritrea

The chapter describes how Asmara was constituted first in text and then became an adaptable setting for the making of a colonial and later Imperial city. Much like maps, previously unseen or unknown spaces are opened up and revealed by colonial descriptions. The map as text and text as map both involve the registration of symbolic languages in space. Michel de Certeau elucidates an essential distinction between the map and the tour by which shifts occur among meanings between two-dimensional representations and the passage of space across time. He affirms, “Maps, constituted as proper places in which to exhibit the products of knowledge, form tables of legible results.”7 The early narratives of Eritrea are stories of arrival and departure, identification and dislocation. Like maps, subsequent narratives of Italian East Africa, “display the perceptual categories and the patterns of inference which determine the colonizers’ view of the colonized; they indicate the desires, investments and projections that are central to the settlers’ existence among the indigenous population of the new empire. Above all, they reveal the limitations of the imperial rhetoric of which they, the travel texts, are part.”8 Italian colonization sought to remake the landscape while simultaneously reshaping its inhabitants. These narrations of a colony-in-the-making took on a moral stance while being didactic. The chapter thus interrogates the social, geographic, and representational mechanisms that generated Italian colonial space in Eritrea. In turn, the chapter illustrates how the assent or rejection of specific components within narratives of form, of landscapes, eventually affected the building of divergent modern visions in Asmara.

Accounts of the northeastern region of Africa, often deemed the Horn of Africa, produced locations in the early twentieth century that were considered an intersection of a mythic and commercial imaginary. The first documented Italian exploration in the northeast region or “horn” of the continent is dated to the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries when travelers passed through areas of Abyssinia.9 Antonio Bartoli, a Florentine trader, entered the region in 1390. Seventeen years later, Sicilian Pietro Rombulo is known to have visited zones of Abyssinia as well. Two Italian cartographers, Pietro del Massajo and Fra Mauro, also endeavored to plot an Ethiopian geography during the medieval period in 1454 and 1469 respectively. Much later, the search for the source of the Nile River also brought a number of expeditions to the region.10 Several groups of explorers are known to have traversed territories along the Red Sea coastline in the mid-seventeenth century but it is unclear if they passed farther than the mountain chain that divides coastal Eritrea from its highlands.11 The first Italian state-sponsored geographic expeditions to the Eritrean coastline occurred over a long period in the late 1870s with full-scale occupation beginning in 1885. However, initial attempts at establishing a semi-permanent Italian settlement were spearheaded by a small band of Lazarist missionaries and militiamen in Assab and Massawa in 1869.12 Led by Giuseppe Sapeto and the Genoa-based Rubattino Shipping Company [then part of the Navigazione Generale Italiana], a small plot of land was purchased in Assab for 8100 Maria Theresa Thalers from Sultans Ibrahim and Hassan Ben Ahmed. By 1888, one of the first published accounts of Enrico Tagliabue, political hand and explorer, a former resident of Massawa for a decade, was published in Milan to critical acclaim. Dieci Anni a Massawa [Ten Years in Massawa] is one the earliest written descriptions of the Eritrean highlands and Asmara by an Italian resident. A combination of field report, memoir, and public reckoning for colonial and militaristic intervention, Tagliabue’s meditations on the landscape and peoples he encountered in his frequent expeditions from Massawa foretell a landscape that is soon to be occupied by Italian forces.

On the heels of Tagliabue’s successes (he had in fact returned to Italy soon after the publication) a number of other books and reports concerning Northeast Africa were published in Italy. Fueled by the longing for images of the far-flung reaches of Italian wherewithal, such documents described the military conflicts and meditations of explorers. While diverse, these texts allocated the potential economic windfall if and when the Italian government was to fully engage in a colonial effort. Adolfo Rossi’s 1894 L’Eritrea com’è oggi [Eritrea is (like) Today] is a collection of his personal impressions as an Italian military officer crossing Eritrea during his return from the bloody skirmishes at Agordat in western Eritrea. Although he ultimately does return to Italy, Rossi’s fleeting, occasionally perceptive commentary on the cultural and social landscapes of Eritrea can be described as influencing a number of other expeditions to visit the area that began in the first years of the twentieth century. Such is the example of geographers Olinto Marinelli and Giotto Dainelli, who, under the auspices of the newly created Società Geografica Italiana, covered the greatest and most difficult of distances in Eritrea and the region as a whole. In their published reports of 1908, the landscape of Eritrea signifies transparencies across scientific and political associations. The landscape, despite its harsh realities, was documented by the team’s apparently simultaneous on-site photographs and written analysis. Independent of Marinelli, Giotto Dainelli’s writing, often taking the form of personal letters or journal entries, proceeds from a fundamental understanding of the Eritrean landscape as an innately “savage” zone into which only an Italian “civiltà” may begin to alter that which remains elusive.

Indeed, the colonial government installed first in Massawa and later transferred to Asmara will bring about manifestly different social and physical changes to the imaging of colonial Eritrea. The first civilian governor named in 1897, Ferdinando Martini, kept a profusion of personal and governmental writings that still resonate among historians of post-independent Eritrea. The first volume of his diaries, published upon Martini’s return to Italy after a decade abroad, can be read as invested with the author’s own mal d’africa [Africa sickness], a spiritual disease of longing for that which once was.13 The term mal d’africa has its foundation among the early writings by adventurers and colonials on the continent. Part melancholy, part irritation, the phenomenon has been adopted colloquially by contemporary Italians and other travelers who, upon returning to their respective countries, feel a loss for the places and persons visited. Martini’s authority within the embryonic colony, as a plenipotentiary civilian among other civilians, will establish the course of Eritrea for successive years.

One of the most significant colonial texts during these years remains the 1901 memoir and autobiography Tre Anni in Eritrea [Three Years in Eritrea] by Rosalia Pia...