- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Explorations in Neuroscience, Psychology and Religion

About this book

In the 1990s great strides were taken in clarifying how the brain is involved in behaviors that, in the past, had seldom been studied by neuroscientists or psychologists. This book explores the progress begun during that momentous decade in understanding why we behave, think and feel the way we do, especially in those areas that interface with religion. What is happening in the brain when we have a religious experience? Is the soul a product of the mind which is, in turn, a product of the brain? If so, what are the implications for the Christian belief in an afterlife? If God created humans for the purpose of having a relationship with him, should we expect to find that our spirituality is a biologically evolved human trait? What effect might a disease such as Alzheimer's have on a person's spirituality and relationship with God? Neuroscience and psychology are providing information relevant to each of these questions, and many Christians are worried that their religious beliefs are being threatened by this research. Kevin Seybold attempts to put their concerns to rest by presenting some of the scientific findings coming from these disciplines in a way that is understandable yet non-threatening to Christian belief.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Explorations in Neuroscience, Psychology and Religion by Kevin S. Seybold in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Neuroscience

The Society for Neuroscience is a professional organization that was formed in 1970 with around 500 charter members. Today the Society has over 36,000 members from around the globe and is the largest group of scientists devoted to studying the brain. At a recent annual meeting in San Diego, California, nearly 31 000 people attended the five-day convention meant to provide a means of disseminating the very latest research results on the brain, the most complicated organ of the body. To go to an annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience is to be impressed by the size and range of the research that takes place in the neurosciences. Alzheimer’s disease, ion channels, memory, long-term potentiation, motor systems, gender, membrane receptors, mood disorders, vision, pain, the immune system, ethics, cell division, neurotransmitters and Schwann cells are just a few of the topics one could read or hear about at the annual meeting. So many researchers present their findings at the convention that only the largest of the convention centers in the United States can hold the throng. A relatively small number of researchers present their work orally in ‘paper sessions’ attended by a few dozen to a few hundred interested peers. The vast majority of the research is reported in ‘poster sessions’. The results of literally thousands of research studies are presented on six-foot by four-foot standing posters that fill the floor of the convention center. Researchers roam from poster to poster to read the latest findings in the areas of investigation that interest them. In addition to the poster and paper presentations, there are more informal and relaxed social gatherings of people interested in similar subjects. Thus, there is the Vision Social, the Cajal Club Social, the Hippocampus Social, the Songbird Social, and the ominous-sounding Cell Death Social, among many others. There really is something for everyone.

Despite its enormous size, the convention is remarkably well run. Transportation is provided from outlying hotels to the convention center, food is easily available at the convention center itself or the many restaurants in the surrounding area, and the program runs from mid-morning to late evening. Attending an annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience is both mentally stimulating and physically exhausting. It does have, however, a kind of bazaar-like feeling, with people moving from poster to poster or seminar room to seminar room listening to the spiel of the scientists ‘hawking’ their research results.

A Brief History of Neuroscience

As suggested by the tremendous growth in the Society since its founding, scientific interest in the brain increased significantly in the latter part of the twentieth century. The number of graduate programs in neuroscience also grew during this same period, as did the number of academic journals devoted to research on the brain. Despite this recent surge in interest in the brain and nervous system, evidence from paleontology suggests that early humans already suspected that damage to the brain could not only produce disabling injuries, but could also lead to death itself (Finger, 1994, p. 3). Trephines, holes drilled in the skull, indicate that humans 10 000 years ago believed the brain was somehow involved in the higher mental functions, in that the trephines were associated with rituals whereby the survivor was seen as having special or perhaps magical mental powers. Another view of the trephines is that the boring of the holes in the skull was a treatment for headaches, mental disorders or perhaps even demon possession (Finger, 1994, p. 5).

In ancient Egypt and Greece, as well as in ancient China, there were differences of opinion as to which organ of the body was the most important in so far as the ‘mental’ capacities of the individual were concerned. Some believed that the brain was the center for mind or soul, but a significant number of others held that the heart (or perhaps the liver) was the seat of the faculties associated with soul. The Greek philosopher Plato (c. 427–347 BC), for example, argued for a three-part soul, one part of which (the vegetative) was associated with the liver, one (the vital) with the heart, and one (the immortal, rational soul) with the head. Plato’s student Aristotle (384–322 BC), however, held that while the soul was the form of the body (it was both everywhere and nowhere), the heart was the center of intellectual activity (Marshall and Magoun, 1998, p. 27). This made sense to Aristotle, in that, being an anatomist and embryologist, the heart was the first organ he could see in the embryo (Zimmer, 2004, p. 13). In early Christianity, the heart became the site for the passions as well as for moral conscience (Zimmer, 2004, p. 16). In the famous painting ‘Light of the World’ by William Holman Hunt which hangs in St Paul’s Cathedral in London, it is at the heart’s door that Jesus knocks, waiting to be let in.

The Roman doctor Galen (130–c. 200) suggested that the liver, heart and brain together are involved in the soul-like powers of the body. The liver filled the blood with natural spirits which were then passed on to the heart, where they were pumped, along with the blood, to the various muscles and organs of the body to be used as nourishment. Some of the blood, however, went from the heart to the head, where the blood passed through a series of vessels called the rete mirabile (marvelous network). Passing through this network transformed the natural or vital spirits in the blood into animal spirits which were capable of thought as well as sensation and movement (Zimmer, 2004, p. 15). These animal spirits filled the hollow cavities in the brain called the ventricles, so while the brain was recognized in Galen’s scheme, it was actually the ventricles that were crucial. The brain, like the heart, served as a pump; intellectual capacity itself was located in the hollow cavities within the head.

Galen made his observations from the dissection of animals and random encounters with wounded soldiers. (Human dissection was prohibited in the Roman Empire.) Relying on these observations, and despite his reverence for Aristotle’s work, Galen identified the importance of the brain over the heart, based upon his tracing of the nerves from the sense organs to the brain. While these dissections were crucial to the development of his theory, the fact that he did not perform dissections on humans resulted in errors and limitations in his theories. For example, the very important role of the rete mirabile in the transformation of vital spirits to animal spirits in the brain is diminished when one recognizes that there is no marvelous network in humans (Finger, 2000, p. 47).

Galen’s view of the soul was still dominant into the 1600s. During this century, however, the work of Thomas Willis (1621–1675) clarified the importance of the brain itself, not the ventricles, in intellectual and mental functioning. Willis was a physician and experimentalist. Some of his patients experienced various kinds of mental or intellectual disturbances during their lives, and when these patients died, Willis was often able to convince the next of kin to allow him to perform an autopsy or post mortem on the body. As part of this procedure, Willis would remove and dissect the brain in an attempt to correlate the person’s intellectual or mental impairment with an observable lesion in brain tissue. As a result of his investigations, Willis increasingly was able to demonstrate that the functions normally attributed to an immaterial soul (located in the heart or brain) were actually performed by the physical structure of the brain itself.

The extent to which these mental and intellectual functions are localizable to specific brain regions became an important area of investigation after Willis and into the twentieth century. (Actually, it remains a controversial topic even today, as we will see in later chapters.) Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828) believed that the cortex of the brain was composed of several distinct regions, each of which was responsible for a particular mental faculty. For example, there were regions, unique to humans, which controlled wisdom, kindness, religious sentiment, even poetic talent. In addition, there were faculties humans shared with animals such as pride, vanity, sense of place, and affection. In total, there were 27 different faculties of mind in humans, each with a particular region of the cortex responsible for it. The movement known as phrenology was based upon the notion of localization of function and spread throughout Europe and America. Phrenology, a term never used by Gall but popularized by his disciple Johann Spurzheim, proposed that a person’s mental and intellectual capabilities could be determined by feeling a person’s skull. The skull, the phrenologists incorrectly believed, corresponded to the underlying brain surface. Excesses in a particular brain region would produce a ‘bump’ on the skull over that brain area. Deficiencies in a mental or intellectual function would produce a depression in the skull over that region. Thus, one could ‘read’ a person’s skull and determine in what mental and intellectual faculties they excelled or were wanting.

Other brain scientists investigated the role of the cortex in movement and sensation. Eduard Hitzig (1838–1907) discovered that electrical stimulation near the front and on the top of a dog’s cortex produced movement of the dog’s leg, face or neck muscles on the side opposite the stimulation (Finger, 2000, p. 161). David Ferrier (1843–1928) identified areas in the temporal lobe that seemed to be responsible for hearing and smell, and eventually corroborated the finding of another scientist suggesting the importance of the occipital lobe in vision (Finger, 2000, p. 165). These experimentalists, along with many others, were showing that there were indeed specialized areas of the cerebral cortex, even if the more extreme beliefs of the phrenologists were false.

In the 1830s, the cell theory, the notion that all living things are made of individual cells, was accepted (Finger, 2000, p. 201). This theory, however, did not immediately apply to the nervous system itself. With better staining techniques and stronger microscopes, the cell theory was also accepted for the nervous system by the mid-1860s. Camillo Golgi (1843–1926) developed a silver stain which turned approximately 3 percent of the nerve cells silver and black against a lighter yellow background (Finger, 2000, p. 204). This stain permitted a clearer view of the brain cell and its processes. Modifying and improving on Golgi’s staining technique, Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852–1934) showed that the brain consisted of many individual cells, a concept known as the neuron doctrine.

Obviously, there are many other scientists whose work contributed to the development of contemporary neuroscience, and anything approaching a complete and detailed history of the discipline cannot be attempted in this chapter. This chapter will, however, provide some of the essential principles of neuroscience so that a better understanding of its methods, assumptions and findings will be possible. One of the significant questions occupying philosophy for centuries is that of the relationship between the mind and the body. Today, that question is usually put in the form of: ‘What is the relationship between the mind and the brain?’ Neuroscientists typically respond to that question by taking a position of monism, which is the view that what we call the mind is actually the brain in action. There are variations of this monist position. There is a completely reductive monism which says that there is nothing but the brain (the mind is simply eliminated from all discussion and consideration). There is also a softer kind of monism which suggests that what we call the mind is a property that emerges from the physical brain. Either way, the material brain is clearly the focus of study in the neurosciences, and the goal is to understand behavior and mental functioning in terms of activity of the nervous system.

Another position taken by neuroscientists is that of naturalism. This view holds that explanations for phenomena, in this case the neural basis of behavior, are to be found in natural processes and mechanisms. Supernatural explanations are to be avoided because the methods of neuroscience, like the methods of other sciences, are only appropriate in the search for natural mechanisms. This is not to say that other, non-natural mechanisms are not possible; it is simply to state that if they exist, science is unable to uncover and detect them. As such, a reductionism in method is followed in the neurosciences. The way to uncover the natural mechanisms underlying the neural basis of behavior is to reduce the complex phenomena to simpler, more manageable pieces. By studying these simpler components, and discovering the natural mechanisms that govern them, one can then begin to put the components together to get an idea of how the larger, more complex whole works. This is the methodology followed, and this methodological reductionism needs to be clearly separated and distinguished from ontological reductionism, which is a philosophical position holding that all of reality can ultimately be reduced to the fundamental principles of chemistry and physics. Methodological reductionism is a way of looking for natural mechanisms underlying some phenomenon. It is not a philosophical position suggesting these underlying natural mechanisms are all that exist of the phenomenon. This view does suggest, however, that science is limited, and is only able to investigate and search for these natural systems.

Basics of Neuroscience: The Neuron

The human nervous system is divided into two basic components: the central and the peripheral nervous systems. The central nervous system (CNS) consists of the brain and spinal cord; the peripheral nervous system (PNS) consists of all neural structures outside of the brain and spinal cord. As mentioned above, the nervous system (both CNS and PNS) consists of individual cells. These cells of the nervous system are called neurons, and neurons are like other cells of the body in many ways. Like other cells (skin, liver, pancreas, and so on) neurons have a cell membrane which defines the cell and keeps some things in the cell and other things out. Neurons also have a cell nucleus which contains genetic information, mitochondria which produce energy for the cell, and many other structures that provide for the basic maintenance of the cell. While neurons share these structures and characteristics with other bodily cells, there is one way in which these neural cells are unlike any other cell in the body. Neurons generate and conduct electrical impulses, and these impulses make up the kind of information that the nervous system processes. Everything we perceive, feel, do and think is made possible through the processing of electrical messages generated by and carried along these cells of the brain, spinal cord and peripheral nervous system.

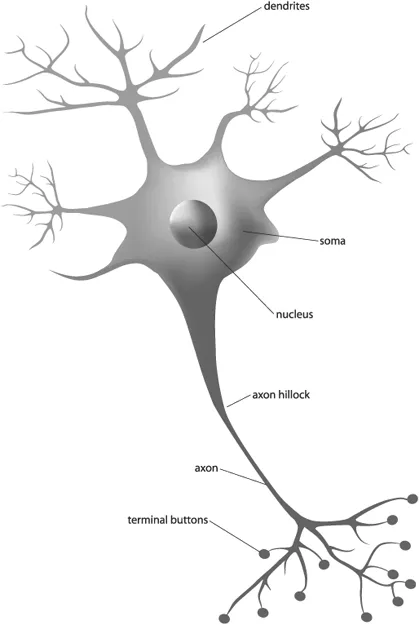

Neurons come in various shapes and sizes. Some are microscopic in length; others can reach a length of several feet. Despite the variations in their size and shape, all neurons have four principal structures: a soma, dendrites, an axon and several terminal buttons (see Figure 1.1). The soma (or cell body) of a neuron contains the nucleus and many of the structures the neuron shares with other cells of the body. The dendrites are those parts of the neuron that typically receive information from other neural cells. (On average, a given neuron in the brain will receive this information from around 10 000 other neurons.) The axon of the neuron is a singular tube-like process that carries information from the soma of the neuron to the terminal buttons, which send the information to other neurons. (On average, a given neuron in the brain will send information to around 10 000 other neurons.) It is estimated that there are between 100 billion and 1000 billion neurons in the human nervous system (Carlson, 2007, p. 30), and some scientists speculate that the number of possible ways these neurons can be interconnected exceeds the number of atoms in the universe. (It is the complexity of the interconnections among neurons that gives the brain its processing power and that results in the emergence of mental states such as consciousness.) The point at which neurons ‘interconnect’ is called a synapse, and this junction between neurons is usually between the terminal button of one neuron and the dendrite of the next. While the term ‘junction’ suggests actual contact between the neurons, in fact they do not touch. There is a small gap, called the synaptic cleft, which separates the two neurons, and this cleft, as discussed below, is an important feature in how these neural cells communicate with each other.

Figure 1.1 The neuron and its principal structures.

Neurons do not exist in isolation, they group together. Within the CNS, a group of somas or cell bodies that are located together is called a nucleus (plural nuclei). A bundle or group of axons that are traveling together from one location to another within the CNS is called a tract. Within the PNS, a group of cell bodies is called a ganglion (plural ganglia), and a bundle of axons is called a nerve. Information traveling toward the CNS (or from a lower area to a higher area within the CNS) is called afferent information, and information traveling out of the CNS (or from a higher to a lower area within the CNS) is termed efferent information. So an afferent nerve is carrying electrical impulses toward the brain or spinal cord, and an efferent nerve is carrying electrical impulses away from the brain and spinal cord. An afferent tract is carrying electrical impulses from a lower brain region (for example, the medulla) to a higher brain region (for example, the thalamus), and an efferent tract is carrying these impulses in the opposite direction.

Additional important vocabulary includes directional terms such as anterior (toward the head), posterior (toward the tail), dorsal (toward the top or back), ventral (toward the bottom or front), and medial and lateral (toward the middle and side respectively).

Neurophysiology and the Electrical Impulse

The only kind of information the nervous system can process and understand is in the form of electrical impulses, and these electrical messages are generated within the neuron as a result of the movement of charged molecules through the cell’s membrane. Some of these molecules, or ions, have a positive charge, others have a negative charge. The most important of these ions are sodium (Na+), chloride (Cl-), potassium (K+) and a group of negatively charged ions given the label A-. The membrane of the neuron is semi-permeable, some of ions can pass through, others cannot. In its unexcited state (that is, the neuron is not generating any electrical impulses), the neuron has a relatively large amount of K+ and A- ions, and small amounts of Cl- and Na+ inside the cell. Outside the cell, there are relatively large amounts of Na+ and Cl-, and small amounts of K+ (A- is only located inside the cell, as these molecules are too big to pass through the semi-permeable neuron membrane.) The distribution of these ions inside and outside of the neuron creates an electrical potential across the cell membrane, known as the resting potential, and is measured at around -65 mV. (The voltage value is preceded by a negative sign because the inside of the cell is negatively charged in comparison to the outside, and by convention the voltage is based upon the charge inside the neuron.) The distribution of the ions is a function of two forces that are present: the force of diffusion and the electrostatic force. Diffusion tends to force the movement of molecules from regions of higher concentrations to areas of lower concentration. As a result, diffusion would tend to push ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of llustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Introduction

- 1 Neuroscience

- 2 Psychology

- 3 Religion

- 4 Philosophy of Science

- 5 Integration Issues

- 6 Brain and Religion

- 7 The Self

- 8 Evolutionary Psychology

- 9 Religion/Spirituality and Health

- 10 The Future?

- Bibliography

- Index