- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

How do precarious workers employed in call-centres, universities, the fashion industry and many other labour markets organise, struggle and communicate to become recognised, influential political subjects? "Media Practices and Protest Politics; How Precarious Workers Mobilise" reveals the process by which individuals at the margins of the labour market and excluded from the welfare state communicate and struggle outside the realm of institutional politics to gain recognition in the political sphere. In this important and thought provoking work Alice Mattoni suggests an all-encompassing approach to understanding grassroots political communication in contemporary societies. Using original examples from precarious workers mobilizations in Italy she explores a range of activist media practices and compares different categories of media technologies, organizations and outlets from the printed press to web application and from mainstream to alternative media. Explaining how activists perceive and understand the media environment in which they are embedded the book discusses how they must interact with a diverse range of media professionals and technologies and considers how mainstream, radical left-wing and alternative media represent protests. Media Practices and Protest Politics offers important insights for understanding mechanisms and patterns of visibility in struggles for recognition and redistribution in post-democratic societies and provides a valuable contribution to the field of political communication and social movement studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Media Practices and Protest Politics by Alice Mattoni in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Advocacy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Theoretical Reflections on the Study of Grassroots Political Communication

Introduction

The precarious workers of the Precari Atesia collective self-produced a radical magazine entitled Sfront End in which they told the stories of ordinary precarity within the call-centre. The activists who organised the Serpica Naro fashion show infiltrated the Milan Fashion Week, a highly newsworthy event, and denounced the diffused exploitation of precarious workers within the fashion industry. During one of the two Reddito per Tutt* direct actions in a mall on the outskirts of Rome, activists distributed flyers to costumers in which they explained the necessity of income re-appropriation by precarious workers. Students struggling against public education reform during the mobilisations against the Ddl Moratti created their own blogs to clarify why they were part of the precarious workers’ struggles in Italy. Some social movement groups that participated in the Euro Mayday Parade set up a live radio broadcast with activists from a number of European countries so as to clarify that precarity was not just an Italian problem.

These snapshots, which I deepen in this book, exemplify activists’ engagement with a diverse range of communication and mediation channels employed to render precarity a visible social problem for different audiences. They are yet another example of an unrelenting trend in contemporary societies: the passage of political communication through a wide range of media outlets, from the press and television to internet platforms and web applications. Mass media and television, in particular, still function as crucial gatekeepers between citizens and political actors. However, from the 1990s onwards, the emergence of information and communication technologies transformed mainstream-dominated media systems into multifaceted media environments. The configuration of the media ecology changed and today a number of media outlets and technologies coexist and recombine in the daily lives of individuals. Proliferation processes (Dahlgren 2009) have rendered the media more multiple, interconnected and diverse than in the past. This leads to the transformation of political communication, which also passes through a variety of media channels and media texts. Election campaigns, for instance, entered a stage in which political parties pair the use of digital media, from personal websites to social networking platforms, with the employment of mass media (Norris 2000).

While the political communication of institutional political actors has been widely investigated in recent work (Negrine 2008; McNair 2003), there is a lack of research on non-institutional political actors, including social movement groups and social movement organisations. As the five snapshots mentioned above also suggest, these actors play an active role in the creation of political messages in different types of media outlets and technologies. To date, however, systematic theoretical reflections and comprehensive empirical investigations on how they engage in mediation processes have not appeared. This is rather surprising since informal political participation has increased in importance in western countries, especially amongst young people (Spannring, Ogris and Gaiser 2008). Citizens have lost trust in institutional political actors (Dogan 2005) and engage less often in conventional political activities such as voting, party membership and campaigning (Dalton 2002). Yet this is only one side of the story: many individual and collective actions are intrinsically directed to the political level, although they are not usually interpreted as formal political participation. Peaceful and legal actions such as signing petitions or striking, or more disruptive forms of engagement such as occupying a building or blocking the streets with sit-ins are usually either instrumental or symbolic expressions of political involvement (Topf 1995; Marsh 1977). The who, what and where of political participation has shifted towards non-institutional forms of engagement (Norris 2002). Although citizens have moved away from electoral participation and grant less trust to the main actors of representative democracies, they still engage in a variety of political activities which nevertheless tend to challenge and redefine the very idea of democracy (della Porta 2009). In other words, in recent decades there has been a displacement of politics which has shifted to more and more non-institutional sites such as individuals or local groups of citizens involved in political consumerism (Micheletti, Follesdal and Stolle 2004; Stolle, Hooghe and Micheletti 2005; Micheletti 2003), and transnational social movement networks protesting against international summits and organising social fora (della Porta 2007; della Porta et al. 2006; Tarrow 2005). Social movement scholars have proved that informal political participation enhanced by social movement processes is more frequent than in the past (Soule and Earl 2006; Rucht 1998). At the same time, specific forms of legal and peaceful non-institutional political participation have gained legitimacy in western democracies, and are increasingly important channels to promote or resist social, political, economic and cultural change in ‘social movement societies’ (Meyer and Tarrow 1998; Taylor 2000; Rucht and Neidhardt 2002).

Each instance of political participation usually includes and sometimes overlaps with at least one instance of political communication, even where non-institutional political participation such as petitions, boycotts, strikes and street demonstrations is concerned. Despite the existence of broader definitions of political communication as a field of study (Franklin 1995; for two traditional definitions in this direction, see Graber and Smith 2005), the very definition of what can be considered part of the realm of political communication is usually narrow and only recently have some authors in the field defined political communication in broader terms, also considering social movement groups and social movement organisations as active subjects of political communication (see for instance Kriesi 2004; Sanders 2009). This book follows the same broad definition of political communication and analyses how non-institutional political actors such as social movement groups and social movement organisations communicate within and beyond their milieu. The focus is, thus, grassroots political communication, here intended as the wide range of politically oriented media practices performed by those groups of individuals that engage in informal political participation.

In the remainder of the chapter I shed light on the existence of a twofold cleavage that contributes to the fragmentation of knowledge on grassroots political communication. I then discuss early attempts to move beyond this fragmentation considering the formation of public discourses and media-related strategies among social movement actors. Finally, I propose to look at grassroots political communication by acknowledging the existence of a media environment in which different categories of media objects, media subjects and communication flows intertwine, and adopting the media practice perspective to look at how social movement actors interact with the media environment.

Cleavages and Clusters in the Study of Social Movements and the Media

Individual and collective actors that engage in social movement processes are the example par excellence of non-institutional political actors that develop grassroots political communication. The literature on social movements, however, provides only fragmented insights about interactions between social movement actors and the media. When it comes to this topic, a ‘divorce’ still exists between media studies scholars and those belonging to the field of sociology, history and political sciences (Downing 2008, 1996), with social movement scholars still paying only ‘tangential attention to media dynamics’ (Downing 2008, 41).

Regardless of the specific field scholars belong to, the literature on social movements and the media seems to form four clusters around two cleavages. Each medium is both a technological object that occupies a space in the daily environments of individuals and a means that connect individuals to the symbolic world of messages (Silverstone 1994; Silverstone, Hirsch and Morley 1992). This peculiarity, also named ‘double articulation’ (ibidem), renders it difficult to investigate the textual and contextual level of the media in order to impart this intertwining of the material and symbolic sides of mediation processes (Livingstone 2007). Studies addressing social movement processes also face this challenge, which leads to the presence of two main cleavages.

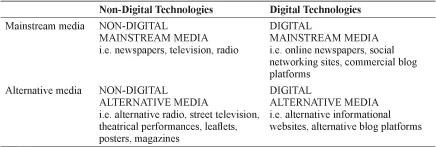

A first cleavage is related to the articulation characterising the media as technological objects. In this regard, the literature on social movements and media organisations and outlets, based on non-digital or analogue technologies, is usually disconnected from literature on social movements and more recent media organisations and outlets based on digital technologies. A second cleavage rests on the articulation characterising the media as means that connect individuals, or better audiences, to different worlds of messages: either mainstream and dominant or alternative and counter-cultural. This leads to a separation between the literature on mainstream media and social movements on the one side, and the literature on alternative media and social movements on the other.

Table 1.1 The twofold cleavage in studies of social movements and media

As I illustrate in the table above, the combination of the two cleavages results in four distinct clusters of investigation that contribute to the fragmentation of knowledge on the topic (Rucht 2011). With a few exceptions (Coopman 2009; Dunbar-Hester 2009; Lester and Hutchins 2009; Rauch 2007), scholars addressing social movements and the media do not usually undertake comparative studies that aim to understand how social movement actors address different types of media organisations, outlets and technologies. Obviously, this body of research started life in a less differentiated media environment, where the boundaries between different technological supports and media messages were fewer and less blurred. Although useful for empirical and analytical reasons, the separations between the four clusters of literature and their related concepts make it difficult to grasp grassroots political communication as it develops in contemporary societies. Examples of multiplatforming content did already exist in the past (for example, Bonner 2009). But today more than ever, individuals deal with diverse media supports: from traditional newspapers and magazines to radio stations and television channels; from internet applications and portable multimedia supports such as mobile telephones, to transnational satellite television channels and web-radio stations. As a consequence, the format of the messages individuals deal with are also more diverse than ever before, they combine different types of languages and are conveyed using a variety of supports. Media messages seem to be more ubiquitous, scattered and less dependent on the technological object from which they originate.

To some extent, the diversity of media outlets and technologies is at the centre of theoretical and empirical research on the public sphere. From Habermas (1989) to his critics (Calhoun 1992; Fraser 1992), scholars studying the functioning of the public sphere suggest that the media play a crucial role in shaping democratic dialogue within societies, and constitute an important element of contemporary public spheres. In recent theories of the public sphere, however, the concept of ‘media’ does not refer only to mass and mainstream media. The general public sphere in which public discourses originate and circulate is seen to consist of three fora: daily encounters among people, public assemblies and the mass media (Gerhards and Neidhardt 1993, quoted in Gerhards and Schäfer 2010). According to Gerhards and Schäfer (2010), e-mail exchanges and private chats mirror the first forum, in which individuals meet and exchange opinions on a daily basis, while blogs, mailing lists and internet fora mirror the second forum of the public sphere, in which individuals gather in public assemblies since these means of communication support the creation of public discussions focused on specific issues amongst internet users. Search engines mirror the third forum, which is the mass media such as the printed press and television, in that they organise content for large audiences (Gerhards and Schäfer 2010). I suggest that the internet applications and web platforms listed by the two authors do more than mirror the offline public sphere. They cross and intertwine with the three abovementioned fora, according to which the offline public sphere is structured. The creation of ‘public sphericules’ based on new technologies may lead to the further fragmentation and segregation of publics in the general public sphere (Gitlin 1998; Sunstein 2002). At the same time, however, claims and discourses made by non-institutional political actors may travel across different technological supports and fora in the public sphere (Bennett 2003). Due to the intertwining of offline and online meetings and encounters, therefore, ‘parallel discursive arenas’ elaborated by ‘subaltern counterpublics’ (Fraser 1992) may also gain space and visibility in societies at large by entering the general public sphere. This is an important opportunity not only at the local and national levels, but also in transnational public spheres where mass media fora are extremely important in shaping public opinion beyond national borders (Downey and Fenton 2003).

The debate about the state of the contemporary public sphere(s) considers new technologies, and especially the internet, as forces capable of reshaping the processes of public discourse formation. It also suggests that to understand grassroots political communication in contemporary societies we should consider the theoretical and empirical musing on the diverse range of technological supports and messages by adopting a cross-media perspective. Similar concerns arise in media studies seeking to understand the mechanisms and dynamics of convergence cultures and transmedia storytelling, according to which cross-platform studies are more likely to capture current communication flows and mediation processes. While investigations related to the public sphere stress the diversity of media technologies and media outlets, media studies address the multifaceted nature of media environments from a different point of view. They recognise diversity, but at the same time stress the separation of the medium and the message on the one side, and the convergence of different media platforms on the other. Departing from these assumptions, scholars argue that individuals live in a ‘convergence culture’ following cultural and technological shifts with regard to how media messages are produced, diffused, received and then recombined once more (Jenkins 2006). There is the need, therefore, to move from a ‘platform-centred’ approach to a ‘content-centred’ approach to follow the travels and transformations of messages across different media devices (Jenkins 2009; Murray 2003).

Social movement studies usually focus on one specific media platform at a time. But social movement actors usually interact with different media organisations and outlets in the course of the same protest campaign. And while some tend to reduce asymmetry with mainstream media, others prefer to focus on reducing dependency on mainstream media and hence engage in the creation of alternative media channels (Carroll and Ratner 1999). The Quadruple-A model (Rucht 2004, 2011) also considers these patterns and maintains that social movement actors may use four types of strategies to react to their lack of resonance in mainstream media: abstention, when the focus shifts away from mainstream media to inwardly-directed group communication; attack, when social movement actors decide to openly criticise mainstream media and sometimes organise violent actions against them; adaptation, when the mainstream media logic is accepted and strategies towards mainstream media are developed accordingly; and alternatives, when social movement actors create their own media to establish a different space in order to communicate both amongst themselves and with broader audiences. Unlike other studies, this model suggests the existence of overlapping practices for dealing with the media, developed according to different logics and purposes. Mainstream media, however, remain at the centre of this model since all the strategies activists may adopt are seen as means to avoid their lack of mainstream media coverage. This book seeks to understand what social movement actors do with the media at large when engaging in mobilisations. In doing so, it departs from a different perspective revolving around the concept of the ‘media environment’ as a whole, in which and through which activists develop multiple ‘media practices’ that frequently overlap. The next section elaborates these two concepts further.

The Media Environment

Some authors interested in social movements and the media have recently acknowledged the need to consider different types of media technologies and messages at the same time. The internet, for instance, should not be considered independently from the traditional mass media (Bennett 2004) and, more generally, some scholars have noted that to understand the role of media in informal political participation, the complexity of the communication flows that shape contemporary societies should be borne in mind (Gillan, Pickerill and Webster 2008; Cottle 2008; Cammaerts 2007a). Drawing on these assumptions, I start from a broad definition of the media environment characterised by three dimensions: the role of media subjects; the type of technological objects; and the direction of communication flows.

Media Subjects

The media environment involves individuals who use technological objects for different purposes and, therefore, play different roles in their regard. In their study on new media in contemporary anti-war movements, Gillian, Pickerill and Webster start from a definition of a (war) media environment revolving around the concept of ‘information sources’. Accordingly, they speak about the existence of an information environment defined as a ‘full range of information resources available to the public, which may extend from recollections of returning combatants to newspaper reportages, from personal experiences of conflict to satellite television coverage’’ (Gillan, Pickerill and Webster 2008, 19). However, Couldry (2002) suggests we overcome the classical division among media producers, media sources and media audiences when dealing with the media. This is even more important when considering contemporary societies where individuals simultaneously play different roles with regard to the media, especially in particular situations of protest, mobilisation and claims making.

Broadly speaking, individuals assume three roles with regard to the media environment: as media audiences they look for information and consume media content; as media producers they create information and originate media content; and as media sources they provide information to other individuals who then elaborate new media content. The three roles are more blurred now than in the past with regard to both portable and fixed digital media devices. On this, for instance, expressions such as ‘prosumers’ (Burmann and Arnhold 2008) indicate the merging of the consumer and producer role in marketing and advertisement studies. An activist, for instance, is (part of) a media audience when sitting in her living room watching a political discussion show about precarity, a media producer when she posts on her Facebook profile information on the next demonstration about precarity in her city and a media source when a journalist interviews her during that same demonstration. Again, however, it is also true that the three roles continue to be separate. Not only because some individuals are more media productive than others, such as professional journalists, but also because the same individual usually experiences the three roles – producer, audience and source – in different situations and contexts. These experiences are particularly important because they are not exhausted in interaction with the media environment. As I will show in Chapter 4, activists also employ their experience as media producers, audiences and sources to interpret the media environment in which they act: they construct semantic maps in which the political and technological dimensions of the media environment combine.

Technological Objects

The media environment includes diverse technological objects that make up the infrastructure within which communication and mediation processes develop. To recognise differences in the type of technological objects is, thus, a first step towards an encompassing definition of the media environment. According to the ‘pervasive communication environment perspective’ (Coopman 2009), media environments include fixed and portable, analogue and digital media platforms that coexist and intertwine. Combining the two dimensions, four main technological objects populate the media environment: fixed analogue media devices like television and radio; fixed digital media devices like computers; portable analogue media devices like newspapers and magazines; and portable digital media devices like smart phones and laptops. The four categories sometimes combine and increasingly converge. The launch of tablet computers, for instance, rendered newspapers and magazines not only portable, but also digital and, as such, certainly more hyper-textual and interactive t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Abbreviations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Theoretical Reflections on the Study of Grassroots Political Communication

- 2 The Discursive Context and Contentious Field of Precarity in Italy

- 3 The Construction of Precarious Subjects in Mobilisations Against Precarity

- 4 Reflections in the Mirror: Media Knowledge Practices

- 5 Surfing Media Diversity: Relational Media Practices 91

- 6 The Construction of Public Identities: Media Representations of Protest

- 7 Conclusions: The Circuit of Grassroots Political Communication

- Methodological Appendix

- References

- Index