eBook - ePub

Digital Games as History

How Videogames Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice

- 290 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Digital Games as History

How Videogames Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice

About this book

This book provides the first in-depth exploration of video games as history. Chapman puts forth five basic categories of analysis for understanding historical video games: simulation and epistemology, time, space, narrative, and affordance. Through these methods of analysis he explores what these games uniquely offer as a new form of history and how they produce representations of the past. By taking an inter-disciplinary and accessible approach the book provides a specific and firm first foundation upon which to build further examination of the potential of video games as a historical form.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Digital Games as History

1 Introduction

Mr. Everyman is stronger than we are, and sooner or later we must adapt our knowledge to his necessities. Otherwise he will leave us to our own devices, leave us it may be to cultivate a species of dry professional arrogance growing out of the thin soil of antiquarian research. Such research, valuable not in itself but for some ulterior purpose, will be of little import except in so far as it is transmuted into common knowledge. The history that lies inert in unread books does no work in the world.

—Becker (1931, para. 22)

I am told it is June the 6th 1944, 6.35am, just off the coast of Normandy. The sky is grey, the water a little choppy. The other soldiers huddling in the landing craft all look scared. Ahead, one of them nervously taps his rifle against the floor. A commanding voice shouts ‘Clear the ramp, thirty seconds!’ Suddenly, I hear the whistling of distant artillery shells answered nearby by crumps of impact and jets of water. Soldiers flinch with each explosion. The occupants of another close-by landing craft all fall injured or dead, strafed by a swooping enemy fighter-plane. We speed past. With a bang our transport stops. The ramp lowers to the sound of artillery and ricocheting machine-gun fire. Suddenly we are underwater. There are soldiers, some dead, some struggling with wounds and the water is filled with blood and whizzing bullets that leaving spiralling patterns in their wake. Breaking the surface I run forward onto the beach. There are bodies everywhere and in the distance huge concrete bunkers spew machine gun fire. The sounds of explosions, gunfire and men screaming are intense and confusing. I can feel the vibrations of these explosions and each impact is met with a geyser of sand. My objective is only to survive. I run towards a crater occupied by one of my compatriots. With a loud bang the air is filled with fire. I pause for a second, startled. Now the crater is empty, its sole occupant vaporised. Just as I am about to reach the comparative safety of the depression, machine-gun fire stitches the sand in front of me. The beach turns black as my perspective falls to the floor, side-on. There is a distant call for a medic, but it is too late. Abruptly I am confronted by two words: ‘continue’ or ‘exit’.

I put down the controller and sat back almost feeling breathless, turning to my friend who had shown me the game and was waiting eagerly to hear my reaction. We sat for a few minutes, inspired at least partly by the sense of disempowerment we were unused to games instilling in us and excitedly discussed how terrible and violent D-Day must have been and what a massive undertaking it was. This was not normally how games made us feel, this was not normally what games made us think. Put succinctly, this experience had stimulated our interest not only in the game itself but also the past that it represented. When I try and think of the first time I had the palpable sense, however basic, that maybe videogames could be history, it is this first encounter as a seventeen year old with Medal of Honor: Frontline (a WWII first-person shooter – ‘FPS’) that springs to mind. Look back at the game through the lens of today’s games and its limitations are so noticeable as to be almost laughable. But for us it was meaningful. It had offered us something we couldn’t express, but it was something different to the ways we normally engaged the past. We hadn’t read history or seen history. Instead, we had played it. Our role was not subsumed. It was in fact the exciting point.

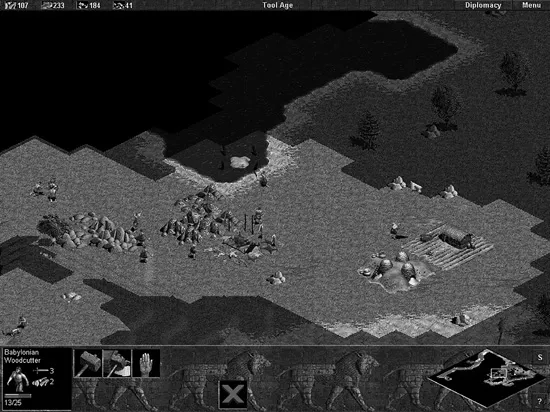

Figure 1.1 Screenshot of Age of Empires.

Looking back now, I realise that although this experience stuck in my mind, it wasn’t actually the first time that I had engaged history through games. Four years earlier, in 1998, I started playing Age of Empires (see Figure 1.1), a historical real-time strategy (RTS) game that focused on the period spanning from the Stone Age to the Iron Age. My mother, glad to see me playing a game with what she perceived to be a little more in the way of substance, was happy to chat about it. We discussed the difference between hunter-gatherer societies and agricultural societies, the changes that the Bronze and Iron Ages had brought about and the importance of technology in history, me drawing on my experiences in the game to do so. Again, we were asserting through our actions, if not our conscious recognition, that games could engage history.

These formative experiences perhaps account for why I have always been so interested in historical games, those games that in some way represent or relate to the past. For me, playing those games obviously felt fun, but I also felt that I gleaned something else from playing them, perhaps some kind of insight, perhaps just a stimulated interest in the past. I imagine that at least some other players (and probably some of the readers of this book) have had a similar sense at some point. Digital Games as History is at least partly generated by curiosity about this sensation. More specifically, this book seeks to examine digital games as a historical form by pursuing answers to three questions: How can we approach these historical games as scholars interested in them? How do they represent the past? What opportunities do they offer players in terms of actively engaging with history and historical practice?

Popular History

History, it is often claimed, is something in decline. The same anxieties seem to be repeatedly revisited. We worry about the state of history education, that too few study too little history and that the general public are disinterested and have too little knowledge of the past. Though these arguments undoubtedly sometimes have validity, generally they rest on the notion that “history” is a thing definable as only synonymous with official, educational, institutionalised and professional knowledge, forms and practices. This means that both the significance of the popular histories found in mainstream media and the nature of history as an active process of remembering performed by the public as well as professional historians, is often missed. Such perspectives generally ignore the role of the everyday, the local, the unofficial, the familial, the popular. Some scholars, journalists and political commentators, for example, are often highly critical and dismissive of popular history (see, for instance, the reactions of some historians to television history in Hunt 2006). These dismissals are often grounded in two common fears concerning popular engagements with history. First, that the public aren’t actually interested in history and that second, the ways in which the public receive history when they actually do so aren’t the ‘right’ ways. It is worth taking some time to examine both of these concerns.

First, it does not seem that the public and popular culture can really be accused of a lack of interest in the past. For example, Rosenzweig and Thelen (1998) discovered, in their seminal study of popular understanding and uses of the past, that (contrary to these perspectives) history was indeed important to ordinary Americans and a part of their everyday lives. This was not necessarily, however, the history found in textbooks. Instead, this was a history weaved with hobbies, collections, local and family history, museum visits and drawn from both multiple cultures (other than the typically rather monolithic national history) and cultural resources. Of course, what those who decry popular engagements with the past actually generally mean when they say that the public are not interested in history, is that the public don’t engage with what they have determined to be the ‘right’ history (whether in terms of accuracy or historical topic). This kind of perspective even infiltrates popular perceptions. An anecdotal example: a friend of mine a few years ago said, rather shamefacedly, that he sadly knew nothing about history. I pointed out that, on the contrary, he actually knew an enormous amount about music history, particularly the history of bands such as The Beatles, The Beach Boys and The Dead Kennedys, their members, performances, music and the genres they emerged from and influenced. Hundreds of hours of research (e.g. reading websites, books, magazines, eyewitness accounts, watching performances and interviews and listening to music – including of course rarer or less well-known demos or recordings) had gone into this knowledge and yet he did not consider this to be history because it didn’t match up with ‘proper history’ – the kind of history we would typically find in textbooks. And yet his dedication, practice and knowledge seemed to show many of the hallmarks of the kind of engagement that this ‘proper’ history is supposed to encourage. This example is hardly an isolated case, many of us know a great deal about the history of whatever we are passionate about, whether sports, cars, music or films, for example, yet many of us would probably similarly position ourselves as knowing little about the past.

It also seems rather strange to point to public disinterest in the past when history seems to be more popular than ever. Historical films such as 12 Years a Slave, Selma and The King’s Speech fill cinemas internationally. Historical novels such as Wolf Hall and The Other Boleyn Girl are bestsellers and have sparked a proliferation of similar novels, as well as being adapted for film or television (TV). Indeed, many of the most popular TV dramas, are also historical, series such as Mad Men, Boardwalk Empire and Downton Abbey. And these series can be found alongside huge numbers of historical documentaries and historical reality TV programmes. When in 2006 Cannadine pointed in History and Media to how in the late 1990s and early 2000s “more history was being produced and consumed than ever before” (1), he also noted that in retrospect these years might end up seeming to be “more like a blip than a boom” (2). However, ten years later, this unprecedented interest in history seems to be showing no signs of abatement.

History Beyond the Academic Word

This brings us back to the second common objection to popular history. The reason that there are still concerns about popular disinterest, despite this proliferation of popular interest in the past, is that these examples (although sometimes engaging the ‘right’ histories) are often dismissed because they occur in forms that emerge from popular culture. More specifically they are not the academic history book that is all too often seen as the only appropriate way to represent and engage the past and therefore as synonymous with history itself. This perspective rests on two problematic assumptions “first, that the current practice of written history is the only possible way of understanding the relationship of past to present; and second, that written history mirrors ‘reality’” (Rosenstone 1995, 49). As Schama notes, this first assumption that “real history is essentially coterminous with the printed book … that only printed text is capable of carrying serious argument” (Schama 2006, 23) is a mistake, because western written history both emerges from oral history and is weaved with a number of continuing performative traditions of engagement with the past. But also because perspectives based on the primacy of the word underestimate the power and capabilities of images (often a part of these popular forms), ignoring work in fields such as iconography and iconology. This ignorance, Schama continues to explain, leads to an understanding of images as only expressive of culture (e.g. politics, economics and religion) rather than also possessing the power to constitute it. Furthermore, “If it is true that the word can do many things that images cannot, what about the reverse – don’t images carry ideas and information that cannot be handled by the word?” (Rosenstone 1995, 5). This is an important idea that will be returned to throughout, that perhaps comparisons between historical forms should therefore not be focused on judgements about what is ‘better’ or ‘worse’ but what is different and what types of engagement with the past this allows. After all, even “language itself is only a convention for doing history – one that privileges certain elements: facts, analysis, linearity. The clear implication: history need not be done on the page” (Rosenstone 1995, 11).

Although this means that the chosen form is an important part of how history is constituted (as this book argues), the changes that other forms introduce are not to the extent, epistemically speaking, often imagined by critics. As Munslow explains, “in turning the content of the past into a form like film we are actually not doing much that is very different in narrative-making terms than historians do when they write (2007a, 568)”. For example, historical filmmakers, just like historians, “use preferred arguments, sift the past ideologically, emplot, select the sources to be offered ‘in evidence’, focalise, contract and extend time, make decisions about the relative merits of structure over agency, use rhetoric, acknowledge the role of the reader/viewer, employ inference, and so on” (Munslow 2007a, 569). The same can be said of historical TV drama makers, authors of historical novels, and as I will argue, digital game developers. All these producers of history, regardless of form, make meaning out of the past, they both engage and produce the larger historical discourse and their produced histories are referential – that is to say they are constructed in relation to other narratives about, and evidence of, the past. Problems with identifying these other popular forms as capable of being history only arise when first, as Schama argues in relation to historical television, we judge them “by the degree to which the preoccupations of print historians are faithfully translated and reproduced” (2006, 24). Comparisons of this kind, across not only forms but also differing arenas of historical practice (i.e. the professional and popular), are unfair and comparing the content of popular history in its multitude of forms to professional printed history tells us nothing about the possibilities of these forms.

As these arguments hint at, the rejection of popular history is often not only based on the idea of the primacy of the written word but also the sole primacy of the academic word. However, this ignores that even the claims of academic history as to its mirroring of past realities, capturing the complete truth, have become more uncertain. As Rosenstone puts it, “historians tend to use written works of history to critique visual history as if that written history were itself something solid and unproblematic” (1995, 49). However, the linguistic turn and various postmodernist perspectives have questioned the supposedly unimpeachable authority of written academic history over the past few decades. This is not the place to rehash these debates and the legacy of postmodernism is still arguably undecided. However, it is probably not too much to say that it is more difficult to find a historian in the contemporary landscape of the discipline that does not harbor at least some doubts about the capability of even academic history to truly and entirely capture and reflect the past. Most historians probably (hopefully) have a sense, for example, that history is always constituted under moral and ideological assumptions or decisions, that “all history is situated, positioned and for something or someone” (Munslow 2007b, 41). That history as a narrative pursuit, even on the page, is partly subjective and therefore “has never simply reflected or captured the meaning of the past, but has always created meaning for the past” (Rosenstone 2007, 594). And that history is therefore a fictive construction, neither entirely factual nor (still being based on evidence) ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- PART I Digital Games as History

- PART II Digital Games as Historical Representations

- PART III Digital Games as Systems for Historying

- PART IV Digital Games as a Historical Form

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Digital Games as History by Adam Chapman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.