- 222 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

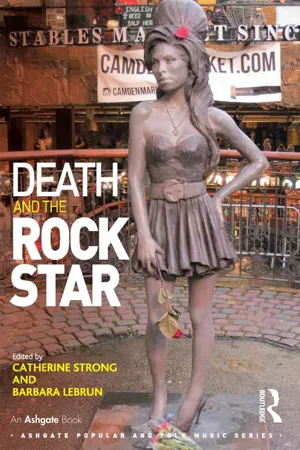

Death and the Rock Star

About this book

The untimely deaths of Amy Winehouse (2011) and Whitney Houston (2012), and the 'resurrection' of Tupac Shakur for a performance at the Coachella music festival in April 2012, have focused the media spotlight on the relationship between popular music, fame and death. If the phrase 'sex, drugs and rock'n'roll' ever qualified a lifestyle, it has left many casualties in its wake, and with the ranks of dead musicians growing over time, so the types of death involved and the reactions to them have diversified. Conversely, as many artists who fronted the rock'n'roll revolution of the 1950s and 1960s continue to age, the idea of dying young and leaving a beautiful corpse (which gave rise, for instance, to the myth of the '27 Club') no longer carries the same resonance that it once might have done. This edited collection explores the reception of dead rock stars, 'rock' being taken in the widest sense as the artists discussed belong to the genres of rock'n'roll (Elvis Presley), disco (Donna Summer), pop and pop-rock (Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston, Amy Winehouse), punk and post-punk (GG Allin, Ian Curtis), rap (Tupac Shakur), folk (the Dutchman André Hazes) and 'world' music (Fela Kuti). When music artists die, their fellow musicians, producers, fans and the media react differently, and this book brings together their intertwining modalities of reception. The commercial impact of death on record sales, copyrights, and print media is considered, and the different justifications by living artists for being involved with the dead, through covers, sampling and tributes. The cultural representation of dead singers is investigated through obituaries, biographies and biopics, observing that posthumous fame provides coping mechanisms for fans, and consumers of popular culture more generally, to deal with the knowledge of their own mortality. Examining the contrasting ways in which male and female dead singers are portrayed in the media, the book

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Death and the Rock Star by Catherine Strong,Barbara Lebrun in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

MusicChapter 1

The Great Gig in the Sky: Exploring Popular Music and Death

Death and the Rock Star examines the ways in which the deaths of popular musicians trigger new affective, aesthetic and commercial responses to their life and work, focusing on a range of interested parties that includes fellow artists, industry professionals, the media, political representatives, fans and family members. Our curiosity in this topic stems from our common interest in artists who committed suicide, whose musical identities we have examined elsewhere – Kurt Cobain of the grunge group Nirvana (Strong, 2011), and the Franco-Egyptian pop singer Dalida (Lebrun, 2013). Beyond music genres and generations, as well as beyond gender and continents, these two deaths have tended to seal the identity of the singers as ‘tragic’, in line with the Western, romantic fascination with the figure of the doomed artist. The manner of their deaths and the way they were mediated have, then, considerably restricted the musical meanings of their outputs. Meanwhile, their deaths have also triggered touching displays of empathy among fans worldwide, and greatly expanded the commercial possibilities of their music thanks to posthumous releases, covers, tributes and other forms of memorial processes that generate new pathways for emotional attachment, and additional revenue. It is this paradoxical power of death, its capacity to simultaneously restrict and expand meaning and possibilities, that this book addresses.

This is not a radical or novel ambition. Rather modestly, this book seeks to complement and expand our understanding of the ways in which our societies respond to the death of music celebrities, and how an artist’s death affects the promotion, mediation and reception of their music. It does so by inserting itself into the growing trend for the study of popular music and death, and of popular music and death-related topics such as illness and ageing (Bennett and Hodkinson, 2012; Forman and Fairley, 2012; Jennings and Gardner, 2012). Specifically, the majority of our contributors acknowledge their debt to the rich and lucid collection by Steve Jones and Joli Jensen, Afterlife as Afterimage: Understanding Posthumous Fame (2005), which was the first to deal in depth with the fact that death modifies the celebrity status of popular music artists and the reactions of their fans. The present collection is less based in fandom and celebrity studies, but adds to Jones and Jensen’s volume by covering several disciplines ranging from sociology and ethnography to film studies, cultural studies, legal studies and musicology. In doing so, this book addresses some of the important cultural and technological changes that have taken place since the publication of Afterlife as Afterimage.

Indeed, the last 10 years have seen the quick succession of high-profile deaths by artists such as Michael Jackson (2009), Amy Winehouse (2011), Whitney Houston, Donna Summer, Ravi Shankar and Robin Gibb of the Bee Gees (all 2012), Lou Reed and JJ Cale (2013) – several are discussed here. There have been key technological improvements allowing for the mock-resurrection of artists through audio-visual duets between the dead and the living. Social media platforms such as Twitter, which launched in 2006, have also allowed for new fan-driven mourning activity. Increasingly, too, local and national authorities have recognised the symbolic and commercial advantage of commemorating the death of popular music artists, whether by organising state funerals, sponsoring memorial monuments or dedicating key dates in the calendar to tributes.1 All these new trends, alongside older ones, are addressed here.

These trends are also examined through case-studies of artists drawn from the broad genres of rock, rap, pop, disco, punk and Afrobeat (the ‘rock star’ part of this book’s title must be taken loosely). The artists principally discussed are the British Freddie Mercury, Ian Curtis and Amy Winehouse; the Americans Whitney Houston, Donna Summer, Kurt Cobain, Michael Jackson, GG Allin, Elvis Presley, Nat ‘King’ Cole and Tupac Shakur; the Australians Paul Hester, Chrissy Amphlett and Rowland S. Howard; the Dutch André Hazes; and the Nigerian Fela Kuti. Beyond the diversity of their musical expression and their varying degrees of fame, these artists have in common the fact of being now dead, and the capacity of their death to infuse new meanings into their recorded outputs.

Before presenting the key themes, arguments and methods of each chapter, we provide some brief context on the intersection of popular music with death. Indeed, why death and popular music in the first place? What is the nature of the relationship between the biological reality of death and the artistic practice of popular music? Is popular music as a medium affected by death differently from other artistic expressions?

Death and Popular Music

Firstly, the definition of the term ‘death’ cannot be taken for granted. Pragmatically, ‘death’ is the cessation of life, the ending of vital functions in biological organisms. Beyond this simple definition, however, lurks a bundle of philosophical and empirical paradoxes, which affect cultural production and the social meanings attached to it. For death is also, as perceptively explained by Vladimir Jankélévitch (1966), simultaneously banal and mysterious: banal because every human body undergoes this process following their birth; yet mysterious because it is intangible until it happens, and it only ever affects an individual once. Death is familiar, regulated, an administrative formality to be declared; yet someone’s death is always unheard-of, a scandal, an extra-ordinary event. Death in that sense is ‘an always new banality’, a most profound metaphysical puzzle (Jankélévitch, 1966 pp. 6–8). Understandably, this puzzle has preoccupied human beings ever since they first comprehended their own mortality.

Attempting to define death thus involves thinking about the attitudes and behaviours of the living (Jankélévitch, 1966 p. 33), for only those who outlive the dead, who experience a person’s death by proxy, continue to make sense of the dead person, of themselves and of the world around them. Put slightly differently, one person’s death only takes on its meaning beyond itself, in the social practices of those around the dead, and these practices are, like all human behaviour, imbued with symbolism and belief (see Berridge, 2001 p. 268). It is the role of cultural activity, then, to deal with death, to explore and elucidate it, to confront and confound it, to forget and cheat it. It is even likely that, as Zygmunt Bauman suggests (1992 p. 31), our acute self-awareness as mortals explains all cultural activity in the first place: ‘there would probably be no culture were humans unaware of their mortality; culture is an elaborate counter-mnemotechnic device to forget what they are aware of’. Thus, from humble daily objects to precious or large-scale sculptures, through to whole cities and empires, human activity and cultural production can be seen as an attempt to defy our mortal condition by creating something that outlives us. By having their portraits painted, their deeds recorded or simply their patronage noted, patrons of the arts have, likewise, strived for a piece of immortality (Assmann, 2011).

Music is one artistic practice that has served to explore our relationship with death, and although all arts have had a similar preoccupation, the musical works that deal with death have taken arresting and influential forms. In the (post-)Romantic compositions of the 1870s (Saint-Saëns’s ‘La Danse Macabre’, 1874; Mussorgsky’s ‘Songs and Dances of Death’, 1875–7), like in twentieth and twenty-first-century popular music, death has been a key theme in the lyrics and compositions of many artists. Today, entire genres of popular music either are, or are perceived to be, fixated on it, including goth (Hodkinson, 2002), emo (Thomas-Jones, 2008) and several revealingly named heavy metal sub-genres such as ‘death metal’ (Phillipov, 2012) and ‘suicidal black metal’ (Silk, 2013). But the relationship between death and popular music does not stop at thematic inspiration. It also encompasses material constraints and symbolic meanings which distinguish popular music from other art forms, and which arguably tighten its links to both the concept and the physical reality of death.

Firstly, music is, like film, an ‘art of time’ rather than of space, a medium that unfolds sequentially through, and is limited by, time (Elleström, 2010 p. 19). This technical constraint means that a song always foretells an end, and always entails the metaphoric and symbolic death of a human voice. The French chanson theorist Stéphane Hirschi (2008 pp. 33–4), for instance, considers that interpreters and audiences are always aware of a song’s imminent end, and describes each song as an ‘agony’ on one level.2 By contrast, there is no ‘end’ to the still art forms of painting, sculpture and photography, and even a book, whose narrative does end after the last word, remains materially present. When a song reaches its end, however, it is gone. A song’s recorded format and capacity to be played again and again actually heightens that impression, as we emphasise below.

Secondly, and even when visual identity and performance are inseparable from the medium, popular music remains a primarily sound-based art form, relying on musical instruments and a singer’s voice to exist. A singing voice, as Barthes (1992 p. 251) has eloquently theorised, implicitly mobilises the whole body of the singer, by necessitating breathing and by making the singer’s physiological, individual asperities to be heard. Therefore, singing specifically evokes a human’s capacity to be alive, while foreshadowing their (symbolic) mortality due to its time constraint.

The impression that a singer is wholly ‘alive’ may be particularly poignant during an aptly named ‘live’ performance, as in dance and theatre, but the paradox that a song evokes the artist’s capacity to be alive, or their ‘liveness’ (Auslander, 1999), and their mortality as well, is enhanced during audio-recording. Indeed, from its inception in the 1890s, the sound recording technique has had the capacity to ‘freeze a moment in time and move it into the future’ (Laing, 1991 p. 3), thereby allowing listeners to ignore the biological condition of the speaker and to engage with them regardless of whether they are actually alive or dead during the broadcast. Thus sound recording, in addition to producing a strikingly fleshed out form of aural intimacy with another human being, seemingly reverses mortality itself, forging the uncanny experience of simultaneous absence-presence (see Sterne, 2005). If popular music in general evokes human life (the voice we hear is unique, and moving through time), and foretells mortality (a song is about to finish), then recorded popular music in particular evokes death (the singer might as well be dead) while ignoring it (the singer’s death is irrelevant since we can still hear them). The idea of death, then, is core to the conceptualisation and technical possibilities of popular music as a medium.

In addition, the physical reality of death is central to popular music as a practice due to its performative element, its physical embodiment in the gestures of singers and musicians. Indeed, popular music artists project their bodies in a presumably more wholesome, direct way than other performing artists whose art also unfolds sequentially, like screen and stage actors. While the latter follow scripts that are rarely self-penned, and knowingly create the illusion of identity through their role-playing, popular musicians and especially singer-songwriters are partly required, and largely perceived, to transmit through their performance something of their ‘real’ emotional self (Weisethaunet and Lindberg, 2010). This corresponds to the imperative of ‘authenticity’, one of the most powerful conventions to have framed popular music since the Second World War, at least in the West, and whose prestige has been central to all the popular music genres since rock music. ‘Authenticity’ remains a key concept in music criticism and popular music scholarship today, despite significant reservations concerning its meaningfulness (Machin, 2010 pp. 14–18).

Nevertheless, this expected overlap between life and art in popular music explains that large segments of the audience frequently develop what they believe to be intimate connections with an artist, sensing that the artist’s life unfolds in their creative works. As several of the following chapters demonstrate, audience members can find themselves profoundly lost when an artist dies, and this sentiment is particularly troubling, and sometimes perversely satisfying, when the artist displayed, during their lifetime, a creative interest in death. For instance, striking effects of ‘authenticity’ whereby life appears to imitate art occurred when the singer-songwriters Ian Curtis (1956–80) and Kurt Cobain (1967–94) committed suicide after composing songs with death-obsessed lyrics, including ‘Existence, well what does it matter?’ in Joy Division’s ‘Heart and Soul’ (1980), and Nirvana’s seemingly programmatic (but actually tongue-in-cheek) ‘I Hate Myself and I Want To Die’ (1994). Likewise, when the American gangsta rap artist Tupac Shakur, who often described and occasionally glorified gang violence in his lyrics, died in a shooting that many believe was caused by a gang feud, the connection between death and popular music took on a strikingly ‘real’ and sinister turn, which later artists have themselves enjoyed exploring (see Williams in this volume).

Lastly, the convergence between death and popular music is particularly striking in sociological terms. For instance, popular musicians tend to die sooner, more unexpectedly and more violently than other artists (and than the rest of us), due to the lifestyles they adopt and the risks they can face. In the UK and USA at least, ‘famous’ rock and pop stars have died younger than the general population and continue to do so until 25 years after they first become famous (Bellis et al., 2007). Similarly, Dianna Kenny (2014) has found that the lifespans of popular musicians were ‘up to 25 years shorter than the comparable US population’, and that ‘[a]ccidental death rates were between five and 10 times greater. Suicide rates were between two and seven times greater; and homicide rates were up to eight times greater than the US population’. Indeed, rock music has claimed young victims from its first days in the 1950s, when artists died violently in plane and car crashes, most famously the Big Bopper, Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens who were all killed on the same flight, aged 29, 25 and just 17 respectively. Popular musicians have also frequently suffered from overdoses of various substances (Jim Morrison, Whitney Houston, Amy Winehouse), or died on and off-stage in sudden ways, from being electrocuted (Leslie Harvey of Stone the Crows), suffering a heart-attack (Mark Sandman of Morphine) or being shot by a crazed fan (John Lennon; Dimebag Darrell of Pantera). The coincidence that many died at the age of 27 has also given rise to one of the most popular conspiracy theories, that of the ‘27 Club’ (see Bennett in this volume).

Thus it is that death, whether as an artistically fruitful theme, as a symbol embedded within audio-recording techniques, or as a physiological reality, has become a central element in popular music generally, and in the mediated ‘star texts’ (Dyer, 1998 p. 63) of popular singers and musicians specifically. Death can be, as in the examples explored in this collection, so intimately tied to an artist’s songs, life and star image that it confers a heightened emotional charge to the discourses that surround them. Death can be particularly fundamental, as this book insists, in the meaning-making processes that the entourage of the dead engage in, whether these people are colleagues, fans, journalists or other parties. Examining these processes produces insights not only into how we understand these artists, but also into the ways in which our society relates to death itself.

To facilitate this exploration, this book is divided into four parts: ‘Death and Taboo’, ‘Mediating the Dead’, ‘The Labouring Dead’ and ‘Resurrections’, a grouping we discuss below. Beyond this practical divide, however, all the chapters share a number of similar arguments. In particular, all our authors demonstrate that, once an artist has died, the immediate overwhelming tendency is to pay homage to the dead, to express respect for the musical skills and the creative individuality of the artist, and to mourn through a vast range of new words, gestures, rituals and objects. These can be obituaries by press journalists (Hearsum; Fast), tweets by grieving fans (Miller), covers or new songs by fellow artists (Bennett; Madeley and Downes; Williams), including duets (Williams; Brunt; Arnold). They can be museum exhibitions and stage shows (Gardner), biopics and TV series (Spirou; Miller), memorial sites including street signs (Strong) and statues (Stengs), and of course eulogies and funerals (Dumbauld; Stengs; Miller). The vast majority of these memorialising practices are well-intentioned and generous, artistically inventive and even joyful. They can also be self-centred, however, as when an artist’s death provides an opportunity for record producers and copyright holders to maximise profit (Madeley and Downes), or when fellow artists benefit from the dead’s aura of prestige (Brunt; Williams). Typically, too, memorial practices appear restrictive in reducing the full complexity of an artist’s life and work to a much smaller set of signs, with the tendency to ignore certain aspects and to essentialise others. This book’s chapters develop this point with reference to very different artists.

Part I: Death and Taboo

For many centuries, at least in the West, humans have had a great physical proximity with death, as several generations usually lived together and family members died in the home. This, the cultural historian Philippe Ariès (1974 p. 544) has argued, led to a relationship with death that was relatively comfortable and familiar, as its reality was ever-present. This proximity unravelled progressively, however, first with new inheritance laws in the Early Modern period, then with advances in medicine and hygiene in the second half of the twentieth century. This resulted in the old and the sick dying predominantly in hospitals and care homes, only exceptionally at home, and in our contemporary lack of familiarity with death. Death turned into an ‘unnameable thing’, ‘the ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Contributors

- General Editors’ Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Great Gig in the Sky Exploring Popular Music and Death

- Part I Death and Taboo

- Part II Mediating the Dead

- Part III The Labouring Dead

- Part IV Resurrections

- Index