eBook - ePub

Redisplaying Museum Collections

Contemporary Display and Interpretation in British Museums

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Redisplaying Museum Collections

Contemporary Display and Interpretation in British Museums

About this book

This is the first book to examine, in depth, the multi-million pound redisplay and reinterpretation process in British museums in the early twenty-first century. Acknowledging the importance of the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) as project catalyst, Hannah Paddon explains and explores the complex process, from the initial stages of project conceptualisation to the final stages of museum re-opening and exhibition evaluation. She also provides an in-depth look, using three case study museums, at the factors which shape each museum redisplay project including topics such as museum architecture, government agendas and the exhibition team. Finally, the book offers discussions and conclusions around pitfalls and successes and thoughts about the future of collection redisplay.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Redisplaying Museum Collections by Hannah Paddon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arte & Architettura generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

Over the past twenty years, there has been a transformation in British civic museums, sparked by an influx of money from an unlikely source, the lottery. With this funding, museums have been afforded the opportunity to recreate their spaces, restore their collections and innovate their interpretations. The content of this book, based on empirical fact and museological theories, explores the transformations (or display renaissance) of three British museums and offers a different perspective on the redisplay process, as experienced by those directly involved in it. Interview snippets provide personal accounts of the positive and negative aspects of contemporary redevelopment projects and the factors influencing team members.

My anticipation is that the text will shed light on, and qualify, the current process of museum redisplay in British museums. To this end, the publication is a reflection of the museum sector, its funding landscape and the redisplay opportunities available during the late 1990s to the present day.

This book is not a manual to redisplaying collections; it does not illustrate how to progress through the redevelopment stage from start to finish (see Dean 1999, 2002, Lord and Lord 2001). However, the issues, and factors, raised in this book will guide decision-makers when considering aspects of collection redisplay. It is intended to fill a specific gap in published museological research, that is, explicating collection redisplay projects through case study examples whilst simultaneously exploring the factors affecting project decisions.

This book makes clear the fact that the process and factors affecting the redisplay of collections in the museums studied are generic and applicable to all British museums and their wide-ranging collections.

The Structure of this Book

This book is divided into two parts. Part I: The Process Guiding Collection Redisplay, brings together three chapters that present an in-depth examination of the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) as ‘catalyst’ of contemporary British museum redisplay projects, introduce three case study museums, which are subsequently used throughout the book to demonstrate key research findings, and provide a detailed theorisation of the contemporary collection redisplay process.

This first chapter provides a brief introduction to the book and an overview of each proceeding chapter. It also presents the reference system for direct quotes from research participants.

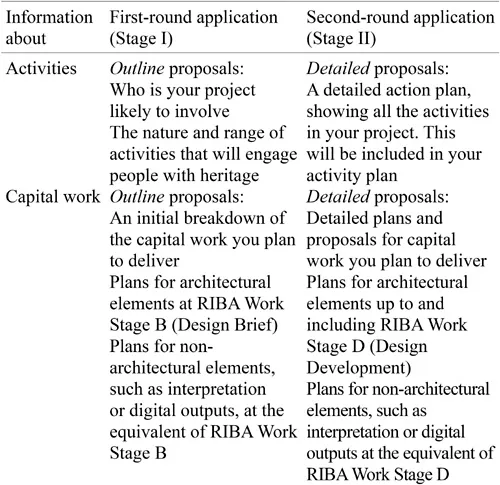

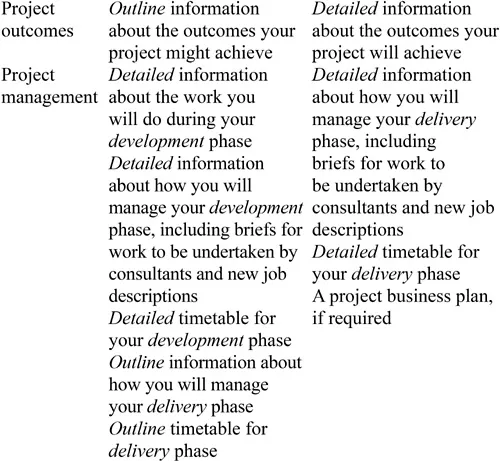

Chapter 2 offers a synopsis of the catalyst for the recent ‘renaissance’: the HLF. Set up in the 1990s, the HLF is a major funding source for museum projects, large and small. As a non-departmental government body, the HLF has revolutionised, and standardised, the way museums afford and carry out collection redisplays. This chapter takes the opportunity to explain the application process, partnerships and the overarching technical project management process in relation to the HLF Heritage Grants programme.

Building upon the first two chapters, Chapter 3 introduces three case study museums; the Great North Museum: Hancock, Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, and Royal Albert Memorial Museum. Details, including historical backgrounds, collection ownership, project backgrounds and the new display approaches provide context to the rest of the book.

Chapter 4 is concerned with drawing out the elements contributing to the structured process of museum collection redisplay. Qualitative research analysis highlights three key elements: decision-making, communication and teamwork. All three components shape project progress, working relationships and, most importantly, the display and interpretation of collections, making each project unique.

Whilst Part I: The Process Guiding Collection Redisplay, explains the process, Part II: The Factors Shaping Collection Redisplay examines the key elements in depth. Within the key elements of decision-making, communication and teamwork are a number of ‘factors’. These factors are explored in separate chapters and are based on empirical research findings across the case study museums. Factors include architecture, power struggles and design.

Chapter 5, the initial chapter in Part II, introduces the factors, and the way in which they are interconnected, through a diagrammatic representation.

Exploring overarching government acts and museum-related initiatives, such as the Disability Discrimination Act, Accreditation and the National Curriculum, Chapter 6 highlights one of the key factors determining the final outcome; stakeholder agendas.

In Chapter 7 the key players in the immediate project team are examined in turn; the curator, educator, designer and project manager. Blended with direct quotes from research participants, the chapter charts the change in the curator’s role from totalitarian redisplay controller to egalitarian team player with a specific team function. The external team member, the designer, has different relationships with each museum team member; in some cases the relationship between curator and designer is limited, and monitored, by the project manager and in other instances the designer is free to discuss visions and issues with the curatorial teams. What is clear is that for each project, the interaction between team members is managed by the project manager in a unique way and, therefore, a unique manner of working is developed.

In ‘Shifting Power: The Audience in the Museum’ (Chapter 8), an in-depth examination of the role the museum audience plays in the development of gallery spaces is detailed. Front-end, formative and summative evaluation is introduced to the reader, with examples of each stage of evaluation illustrated by the case study museums. Whilst this chapter explains the consultative process, it does not detail the intricacies of audience evaluation on aspects such as text, story selection or objects. Audience consultation data was not available from any of the case study museums at the time of this research. However, it is acknowledged that such data may now be freely available, as all three projects are complete. Further research could be conducted to explore the extent to which audiences are impacting decisions such as story and object inclusion.

Chapter 9 explores the multitudinous dimensions of visitor-centred goals; from learning in the museum to cultivating practical skills for use outside the museum. Visitor experience in the museum is a driving factor in the redisplay of collections, as demonstrated by the case study museums.

As part of the move to make galleries accessible to more audience groups, museums are considering the holistic visitor experience. In an effort to be more inclusive, the case study museums are offering different learning opportunities. One of the most notable opportunities is the provision of specific learning spaces in the museums; where members of the public can access collections and members of staff. These factors are dealt with in Chapter 10 of this book.

Balancing the requirements of stakeholders is extremely difficult. Chapter 11 explores the idea that museums in Britain are playing it safe, when it comes to design and themes, to satisfy as many stakeholder groups as possible.

Following on from the previous chapter, Chapter 12 builds on the interplay between stakeholder groups to chart the decision-making difficulties facing museum project teams. Working to balance the desires of funders and demands from external partners, they must also maintain their original project aim and objectives. This juggling act imposes certain stresses and strains on the team. This chapter examines the conflicts of interest between stakeholders; how conflicts erupt and are, in the main, resolved.

Physically impacting the redisplay and reinterpretation process is the Victorian and Edwardian architecture of many local and regional museums in Britain. Chapter 13 investigates the influence aging architecture has on the design of galleries and new interpretive frameworks. It also elaborates one specific finding from the research; the reclamation of space in the buildings for display and the subsequent move of stored collections to off-site storage facilities.

Chapter 14 focuses on the flexibility of these new displays, considering the longevity of previous galleries cases, themes and ‘interactives’. New philosophies are examined and a conversation about the creation of flexible displays brings a new dimension to the decision-making process for redevelopment project teams.

Chapter 15 has been dedicated to the display of biological collections in the twenty-first century. Beginning with a historical overview of biological display from the very origins of the ‘museum’, the chapter continues to characterise displays through the eras culminating in best-practice examples of contemporary display. The chapter then moves to explain the twenty-first century display of biological collections in the case study museums, with examples of emergent topics such as mascotism, design influences and storytelling.

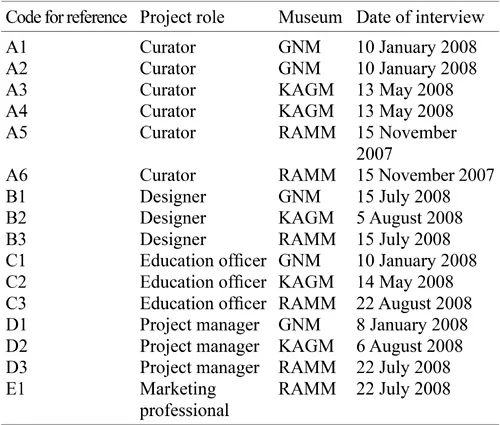

Table 1.1 Referencing system for project team member quotes

Note: All interviews were conducted with the project team members in person at their respective museums, or in the case of the designers, at their offices.

As implied by its title, ‘Lessons Learnt’, Chapter 16 reflects on a variety of issues raised and problems encountered throughout the process of collections redisplay. The experiences of museum professionals and designers presented here can help new projects, and their teams, to avoid pitfalls and realise the importance of remembering the aim and objectives of a project from the outset.

The final chapter in this book draws conclusions about, and provides final thoughts on, the process and factors involved in the contemporary redisplay of museum collections in Britain. The future of collection display is discussed, alongside its process and the factors that shape redevelopment.

Case Studies

In order to explore the complexities of the collection redisplay and reinterpretation process, three case study museums were examined: Great North Museum: Hancock, in Newcastle upon Tyne (GNM); Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, in Glasgow (KAGM), and Royal Albert Memorial Museum, in Exeter (RAMM). This involved interviewing four types of project team members (given the same titles here for ease of comparison): project managers, education officers, curators and external design consultants (designers). There was also one interview with a marketing professional.

Within this book, first-hand experiences expressed by team members and project-specific information is interwoven with theoretical museology. To allow for ease of reading, a referencing system has been devised whereby superscript alpha-numerical references will appear after any quote made by a member of the project teams (see Table 1.1).

Part I

The Process Guiding Collection Redisplay

Part I of this book examines the process of collection redisplay in British museums, the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) as catalyst, the RIBA Plan of Work stages, and the overarching key elements of decision-making, communication and teamwork.

Chapter 2

Catalysing Change: The Heritage Lottery Fund

The Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), which was established in 1994, has been funding heritage projects since its inception. Since that time, the non-departmental public body has awarded over £276.7 million to ‘exhibitions, interpretation, collections management, learning and outreach programmes’ in museums (HLF 2014: 2). And between 1996 and 1997, the HLF embarked on a major funding initiative to grant monies to capital projects for 45 museums and galleries across the UK (HLF 2003).

As a heavy-hitting proponent of the heritage sector, the HLF has affected the museum landscape in Great Britain physically, financially and procedurally. Cities have witnessed their Victorian and Edwardian museums being transformed as a result of the catalytic HLF. For some, the impact has been extremely positive:

… enabling development on a major and visionary scale; putting the museum on the map with all stakeholders; assuring [the] long-term viability of [the] museum; giving non-discretionary access to all collections and services; securing the collections for the future; preserving and extending the useful life of Listed buildings; securing and developing employment opportunities directly and indirectly; enhancing [the] museum’s contribution to [the] local economy. (Selwood et al. 1995: 23).

Grants from the HLF can vary in size (see the ‘Programmes’ section below), but it is in the area of building and collection projects that the HLF has been a leader amongst heritage funding bodies. The HLF’s large grant scheme, Heritage Grants, has been instrumental in propelling capital building projects on an unimaginable scale.

To this end, the HLF has, in the eyes of most, catalysed and enabled sensational change in terms of collection display. It has also facilitated a change in the roles of museum professionals in redevelopment projects.

Programmes

Aware of the need to provide funding for a variety of heritage-based projects, the HLF maintain a range of grant programmes covering a number of heritage areas, with varying levels of funding and criterion (see <www.hlf.org.uk>). Most museums will have been redeveloped as a result of gaining a grant from the Heritage Grants programme. This particular programme supports projects seeking £100,000 or more. One of the caveats to this programme is that the project’s own organisation contributes to the overall project fund; those requesting upwards of £1 million are expected to contribute 10 per cent of the total cost (in cash, non-cash and volunteer time contributions) (HLF 2012a: 8). This competitive programme has a two-round application process (explained further below).

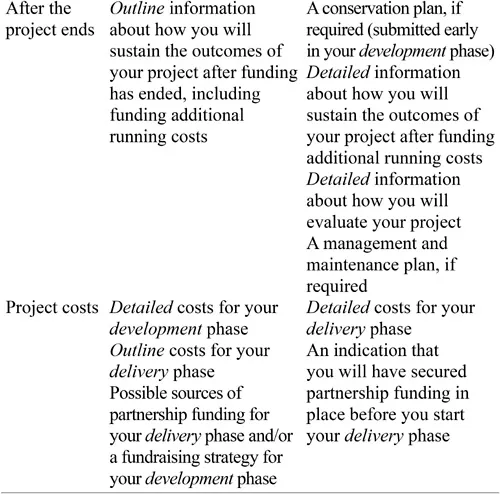

Table 2.1 First-round application information required

Source: HLF 2012a: 10.

Partnership Funding

Because the HLF Heritage Grants programme will not cover the entire cost of a project, museums must look to other sources for grants; they must secure partnership funds. Potential trust and foundation funders are swayed to invest in a project if it has received the proverbial ‘thumbs up’ from the HLF: ‘that was a core bit of funding that was needed to kick start the whole thing and helped us to get match funding.’C1 Funders such as the Clore Duffield Foundation awarded the Great North Museum (GNM) substantial funds for a ‘multi-purpose Clore Learning Suite’ (Clore Duffield Foundation 2013). Other funders of museum redevelopment projects include Arts Council England, CyMAL, DCMS/Wolfson Museums and Galleries Improvement Fund, Designation Challenge Fund, Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, Friends’ groups, Garfield Western, local and regional councils, Museums Galleries Scotland, Northern Ireland Museums Council and Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB).

Whilst larger partnership funding is generally sourced from arts-foc...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- List of Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- Part I The Process Guiding Collection Redisplay

- Part II The Factors Shaping Collection Redisplay

- Bibliography

- Index