eBook - ePub

Approaches to Byzantine Architecture and its Decoration

Studies in Honor of Slobodan Curcic

- 330 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Approaches to Byzantine Architecture and its Decoration

Studies in Honor of Slobodan Curcic

About this book

The fourteen essays in this collection demonstrate a wide variety of approaches to the study of Byzantine architecture and its decoration, a reflection of both newer trends and traditional scholarship in the field. The variety is also a reflection of Professor Curcic's wide interests, which he shares with his students. These include the analysis of recent archaeological discoveries; recovery of lost monuments through archival research and onsite examination of material remains; reconsidering traditional typological approaches often ignored in current scholarship; fresh interpretations of architectural features and designs; contextualization of monuments within the landscape; tracing historiographic trends; and mining neglected written sources for motives of patronage. The papers also range broadly in terms of chronology and geography, from the Early Christian through the post-Byzantine period and from Italy to Armenia. Three papers examine Early Christian monuments, and of these two expand the inquiry into their architectural afterlives. Others discuss later monuments in Byzantine territory and monuments in territories related to Byzantium such as Serbia, Armenia, and Norman Italy. No Orthodox church being complete without interior decoration, two papers discuss issues connected to frescoes in late medieval Balkan churches. Finally, one study investigates the continued influence of Byzantine palace architecture long after the fall of Constantinople.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Approaches to Byzantine Architecture and its Decoration by Mark J. Johnson,Amy Papalexandrou, Robert Ousterhout in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & History of Architecture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArchitectureSubtopic

History of ArchitecturePart I

The Meanings of Architecture

1

Polis/Arsinoë in Late Antiquity: A Cypriot Town and its Sacred Sites

Amy Papalexandrou

The site of modern Polis (ancient Marion/Arsinoë), situated in northwest Cyprus on the Khrysochou Bay, is endowed with archaeological remains attesting to nearly continuous human activity in this region of the island from the Archaic period through the Middle Ages. The material from Polis has been under investigation by a team from Princeton University since 1983, with ongoing research and analysis continuing to the present day.1 The site has proven particularly rich in Late Antique remains, including two Early Christian basilicas discovered near the modern town, the first of which was excavated during the 1980s while Slobodan Ćurčić served as the team's resident authority on all matters Byzantine. It was his initial reading of the Late Antique material at Polis that sparked my own interest in the site, and accordingly this chapter owes much to his guidance and scholarship.2

In the years since Ćurčić's participation on the project, a second church has been discovered at an approximate distance of 200 m from the church he helped to excavate. The proximity of the two buildings, along with their similarities and differences — of form, function, and surrounding context—have become points of interest and invite comparative analysis as a means to better understand not only their respective histories but also the nature of the small urban settlement within which they existed and operated. I offer this brief chapter to Danny in gratitude, in admiration, and in the spirit of inquiry he has helped to foster for the allied fields of archaeology, architectural history, and Byzantine studies.

The Late Antique Town

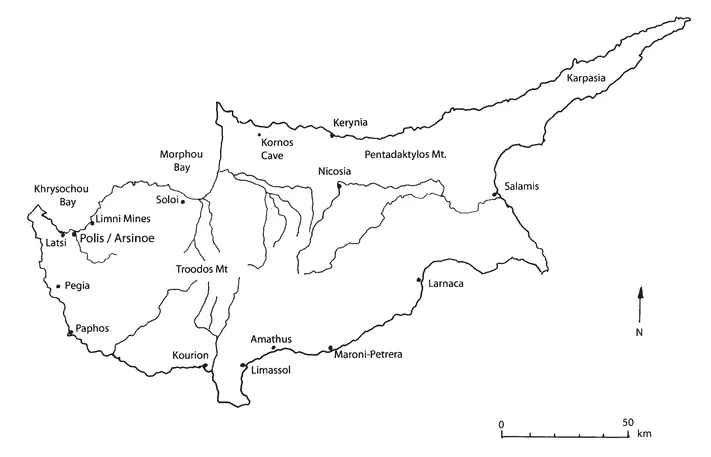

Polis, or Arsinoë as it was known in Late Antiquity, is attested in the historical and epigraphic record as a bishopric from as early as the fifth century CE.3 Aside from its appearance in a single inscription and a few early lists, however, it is seldom mentioned and does not appear in the sources again until much later, following the reorganization of the island under Latin domination.4 The modern tendency is to consider the region — and hence the town — as isolated and provincial. This is based on its current reputation as a sleepy tourist village as well as its remote location, some 35 km north of Paphos near the rugged Akamas peninsula (Figure 1.1). In Late Antiquity, however, as in earlier centuries, it must have been a thriving, if not bustling community. The copper mines at Limni (5 km to the northeast, now defunct) played a considerable role in its economy, and the town's position on a low bluff overlooking the Khrysochou Bay ensured easy access to the sea. Of the latter, a small, as yet uninvestigated, harbor 4 km to the west, at the modern-day fishing village of Latsi, offered maritime communication with the island's nearby cities as well as the ports of the Mediterranean basin beyond.5

Figure 1.1 Map of Cyprus showing locations of Polis and other sites mentioned in the text (drawing: Brandon E. Johnson).

The town's importance is further attested by the excavated remains of shops and/or workshops, wells, water channels and drains, a small network of streets, a modest tetrapylon, and, not least, the existence of multiple churches that served a burgeoning Christian population. Arsinoë must have had at least three and perhaps more ecclesiastical structures, two of which are known from the Princeton excavations and one that was hurriedly investigated by Rupert Gunnis in 1927 near the center of the modern town.6 The metropolitan church of the aforementioned inscription has not been located, although it is conceivable that it was the building explored by Gunnis. The site of the metropolitan church is often said to be the open field behind the present-day excavation house, this due to the periodic discovery there of sculptural fragments and at least one very large 'Theodosian' capital. Traces of what may indeed be an apse wall were pointed out by our foreman in 2008, but no firm evidence supports the notion of a basilica in this location. The small size of the excavated basilicas likely precludes their possible designation as cathedral.

This abundance of ecclesiastical buildings should come as no surprise since it is common to find multiple churches in close proximity within late antique urban centers, even small ones. A body of cultic buildings at Polis/Arsinoë is therefore not exceptional, but at the same time the presence of a number of churches further underscores the importance of the site within a hinterland context at the northwestern margins of the island. Hence, our conceptual image of Late Antique Cyprus should be rethought, with Arsinoë finding its rightful place on the map as an active player in the island's network of coastal cities. This is especially important in view of the seventh-century Arab incursions and the subsequent, profound transformations of settlement and society that these events are traditionally thought to have engendered.

Basilica A and its Cemetery

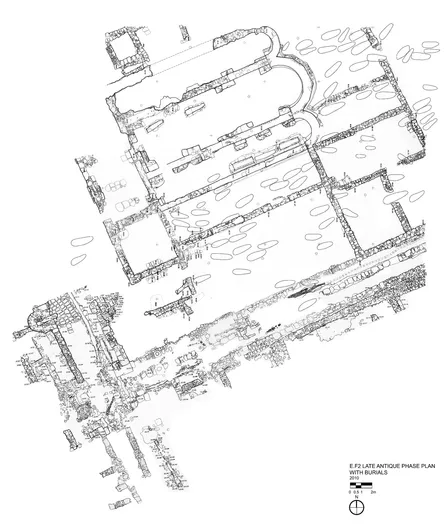

The first major building discovered at Polis (designated here as "Basilica A") was a modest, three-aisled basilica (23 m x 12.5 m) situated just north of the modern town center and directly adjacent to the main road that descends to the sea. Its poor state of preservation has left no walls visible above the level of the plaster floors. In form and decoration it is typical of the myriad churches built during the massive building boom that took place across the Mediterranean Basin, Cyprus included, during the late fifth and early sixth centuries CE.7 It has been dated only approximately to the years around 500 on the basis of fragmentary finds and the historical circumstance of the island's religious autonomy after 488.8 Preceded by a narthex to the west, its three aisles were divided by two colonnades that terminated in three semi-circular apses at the east, the central one externally polygonal (Figure 1.2). The whole was covered by a wooden trussed roof and its interior space outfitted with mosaics and imported marble decoration, many fragments of which survive.

Almost nothing remains of the robbed-out north aisle, but the situation to the south is clear: a portico running the entire length of the building was added to the south aisle soon after the church's initial construction. This space was originally open and articulated with large piers along its south façade, though these openings were subsequently filled in. A square chamber was also added to the south wall of the narthex at the same time the portico was constructed. The narthex did not communicate with an atrium to the west (a situation not unknown in Cyprus), but the south portico opened onto a walled courtyard south of the church.

Basilica A underwent a series of subsequent renovations, all of which involved the addition of piers and accumulation of wall buttresses intended to support masonry vaulting overhead, either as barrel vaults or a dome or both. This will not concern us here other than to suggest that these alterations may have occurred soon after construction, with subsequent renovations into the eighth or ninth century.9 This conclusion, a revision of Professor Ćurčić's earlier dating, is based on the lack of ceramic evidence within the church that would support a later date. Small-scale production and domestic settlement dated to the eleventh and twelfth centuries is apparent in the surrounding structures to the north and south, but within the church itself only a small area at the west end of the south aisle revealed evidence of later occupation, apparently due to squatters. The complete absence of late Byzantine pottery here is interesting and suggests that the population shifted elsewhere at this time—perhaps south toward the modern town center and certainly north to the area of Basilica B. The transformation to vaulting likely followed a general trend on the island, the dating of which remains controversial.10 I turn instead to the contextual surroundings and their eventual funerary function in order to consider the building's role within the Late Antique environment as a whole.

Basilica A was positioned within an area of the city that was traditionally a nucleus of activity, whether industrial, commercial, or both. A kiln had been firing terracotta lamps (under study by Dr. Christopher Moss of Princeton) immediately east of the south apse in the early second century CE, and Roman buildings south of the open courtyard seem to have operated as glass and bronze workshops at this same time. Additional structures, possibly shops, lined a major thoroughfare—complete with covered storm drain and water conduits—running E–W through the southern edge of the excavated area. Two additional streets have been discovered running east and west of the basilica. The church, then, was part of the surrounding urban environment which survived and, for a time at least, continued to function well into the Late Antique period (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Polis, Basilica A and surroundings, site-plan (drawing: Krista Ziemba, Princeton Cyprus Expedition Archive).

An impressive apsidal well-house to the southwest likely dates to this time as does a series of long cobble walls east of the church. The latter belonged to ancillary structures—of unusual, elongated shape and unclear function—that abutted the apses (Figure 1.3). The possibility exists that these may have been storehouses of some type, a suggestion made more interesting by the physical connection of these variously functioning buildings to the church itself. In any case, Basilica A should clearly be viewed as an urban building, one that was superimposed within an area traditionally given over to the production and perhaps retail of various types of small-scale goods. The extent to which this artisanal activity was carried into the Late Antique buildings south of the basilica will be clarified through study, currently undertaken by Dr. Maria Parani of the University of Cyprus.11

The sacred boundaries of the ancient city were no longer at issue in the years following the basilica's construction, a fact made clear by the inclusion soon afterward of burials within the building. A series of three masonry tombs lining the south aisle are the most prominent of these and certainly housed eminent members of the community, whether clerics or lay patrons. These tombs were initially considered later intrusions (Middle Byzantine or later), but their contents suggest a date not long after the building's construction. The central of the three tombs contained a coin dated to the fifth or sixth century (Burial 17: Polis inv. no. R396/NM276), and ceramic evidence is Late Antique. The interment of individuals near the sanctuary is in line with contemporary practice and can be seen in other churches on the island, such as the church at Maroni-Petrera and Campanopetra at Salamis.12

Figure 1.3 Polis, Basilica A, ancillary structure with later burials east of church, from east (photo: Princeton Cyprus Expedition Archive).

Less well-appointed graves were sunk into the plaster floors of the central aisle, narthex, and especially the south porch. The bulk of interments, however, were found around the periphery of the church, where the surrounding buildings and infrastructure of urban life gradually fell into decay and gave way to a large burial ground (Figure 1.2). This is significant, for up to now there have been few self-contained community...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Abbreviations

- A Tribute to Slobodan Ćurčić, Scholar and Friend

- Introduction: Approaches to Byzantine Architecture and the Contribution of Slobodan Ćurčić

- Part I: The Meanings of Architecture

- Part II: The Fabrics of Buildings

- Part III: The Contexts and Contents of Buildings

- Part IV: The Afterlife of Buildings

- Bibliography of Published Writings

- Index