- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reading the Architecture of the Underprivileged Classes

About this book

The expansion of cities in the late C19th and middle part of the C20th in the developing and the emerging economies of the world has one major urban corollary: it caused the proliferation of unplanned parts of the cities that are identified by a plethora of terminologies such as bidonville, favela, ghetto, informal settlements, and shantytown. Often, the dwellings in such settlements are described as shacks, architecture of necessity, and architecture of everyday experience in the modern and the contemporary metropolis. This volume argues that the types of structures and settlements built by people who do not have access to architectural services in many cities in the developing parts of the world evolved simultaneously with the types of buildings that are celebrated in architecture textbooks as 'modernism.' It not only shows how architects can learn from traditional or vernacular dwellings in order to create habitations for the people of low-income groups in public housing scenarios, but also demonstrates how the architecture of the economically underprivileged classes goes beyond culturally-inspired tectonic interpretations of vernacular traditions by architects for high profile clients. Moreover, the essays explore how the resourceful dwellings of the underprivileged inhabitants of the great cities in developing parts of the world pioneered certain concepts of modernism and contemporary design practices such as sustainable and de-constructivist design. Using projects from Africa, Asia, South and Central America, as well as Austria and the USA, this volume interrogates and brings to the attention of academics, students, and practitioners of architecture, the deliberate disqualification of the modern architecture produced by the urban poor in different parts of the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reading the Architecture of the Underprivileged Classes by Nnamdi Elleh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Context(s) and Theoretical Underpinnings

1

Reading the Architecture of the Underprivileged Classes

The goal of this book is articulated in its title: Reading the Architecture of the Underprivileged Classes. A basic definition of the word “read” in the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary is “to look at and understand the meaning of written or printed words or symbols.” From the definition of the word reading, it can be inferred that the essays in this book are taking another look at a widespread global type of architecture in urban centers that were built by people who do not have access to architectural services, albeit mostly in the developing parts of the world. In addition, from the word reading, we can infer that the essays in the book are grounded on the position that architectural forms can be read as social symbols that are imbued with meanings. It follows that the particular understanding sought in the collection is how the drive for social status gave impetus to architectural practitioners and scholars to maneuver with the terminologies used in the description of buildings that emerged in the early part of the twentieth century through the present time in order to determine which structures can be discussed in history books as modern types, and those that should be classified as neither known, definable, nor noteworthy. Unfortunately, it happens that those described as unknown, indefinable and not noteworthy happen to be almost all the varieties produced by underprivileged classes in the developing cities of the world.

There is a lot more to the title of the book: the idea of “underprivileged classes” implies that one of the intentions of the book is to focus attention to the housing problems of people who have little access to economic resources, and subsequently, to buildings designed by architects because they cannot afford architectural services, nor the land to build. If they were able to find a piece of land to build, the quality of the dwelling in the initial stages of establishment was so poor that it can be said no significant improvement was made to the quality of life experienced by the inhabitants of such houses and neighborhoods. Another characteristic the settlements have in common, regardless of where they are located, is that often the builders are new immigrants to the urban centers seeking employment opportunities. They may be unemployed, underemployed, or in full employment, but those in the initial stages of their settlement in their new environment do not earn enough to afford homes in planned and established settlements. Hence, the word “class” is used minimally in this context to describe a group of people and dwellings that share common economic characteristics and interests in the society. We are aware that in a post-Cold War and post-9/11 era when public buildings and infrastructure as well as urban design are being rethought from multiple perspectives pertaining to security, the term “class” can be polemical, and some might go as far as to say it is obsolete in architectural discourses. There is pressure to sublimate and substitute it in critical texts to politically correct words as if it no longer contributes meanings to contemporary architecturally inspired social discourses and consciousness.

There is another perspective from which the words underprivileged class are used to read the architectural productions of people. The emergence of terminologies like ghetto, favela, shantytown, and townships, cannot be traced to an organized conspiratorial single ideological trajectory among the diverse interest groups. Engineers, urban reformers, politicians, philanthropists, religious leaders, industrialists, writers, scholars, governing authorities, revolutionaries, sociologists, workers in factories and the general urban dwellers use those words to describe the residential environments they witnessed. If the varied groups had anything in common, regardless of whether or not their paths crossed each other or they agreed and disagreed with each other, sometimes violently in revolutions, it was the fact that they were living in a world that was rapidly being transformed by industries. The words they used to describe the environments were their way of expressing the social and the physical benefits and the disadvantages of the industrial environment they were witnessing. In this sense, as we saw in the writings of Frederic Engel (1845 and 1987), Ebenezer Howard (1902 and 2008), Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier (1986 and 1987), and (Fishman 1999), architectural objects are analogous to tableaus displaying relief of social contexts and conditions in which destitute urban dwellers were living, and how urban reform was imagined.

For that reason, the words “underprivileged classes” in the title of the book were carefully chosen to demonstrate how the absence or presence of the architects in the design of the built environment reinforces certain social stereotypes when non-architects with little economic means construct their own dwellings in the emerging urban centers around the world. Most importantly it ironically shows how despite the absence or presence of architects’ services in the making of the environments where people of the economically underprivileged classes dwell, the profession has always benefited from remaking neighborhoods that are deemed economically and socially challenged. This observation is more urgent than ever due to increasing urbanization in the twenty-first century, and the anticipation that many architects’ jobs would be created in the underdeveloped parts of our cities. The existing body of literature on the architecture of the underprivileged classes is an opportunity for adopting a reading strategy focusing on the sources of architectural practices that were available in the different localities before the emergence of the types of architectural structures we are studying in this book.

This careful historical reading presents the perspective that the emergence of the architecture of the economically underprivileged classes probably began with the advent of the industrial age in the eighteenth century, when the large coastal global cities in the developing parts of the world began to expand and were gradually being connected to each other by trading linkages. Fortunately, many travel accounts by early explorers provide a plethora of sources from which to draw.

PRE-MODERN CITIES AND TOWNS WITHOUT THE RECORD OF THE TYPES OF “SLUMS” IN OUR DISCOURSE

To verify if architectural historians and scholars have omitted the architecture of the underprivileged classes from history books in the twentieth century, we should first examine what explorers saw when they visited many parts of the world where these structures are still developing. The accounts of the explorers are salient because they were written before the dawn of the industrial age and when the regions rapidly began to participate in trade that stretched across the globe. The trajectory of thought here does not sanitize the cities found by the explorers as settlements free of poor folks and dwellings. No, that is not the idea nor the position of the essays in this book. Instead, it reinforces the existence of vernacular ways of building the environment for the rich and the poor, wherein vernacular is understood here as something made locally by the people with their own technologies and skilled labor. Usually, the building materials and technologies were drawn from the local surroundings. No single account exists of structures built with metallic sheeting and roofing, asbestos, plywood, cement, recycled plastic coverings, glass, straws, sticks and clay as we would find today in the architectural productions of the underprivileged classes.

Consideration of the description of the ancient Empire of Ghana by Abdallah ibn Abdel Aziz, a Muslim scholar based in Cordoba, Spain, who was also known as Abu Abaid, and most popularly by the alias El Bekri, in 1067, grants us insight to an ancient African environment. El Bekri did not mention buildings constructed with manufactured and natural objects as we commonly find in the settlements we are studying. Davidson (1970) reminds us that El Bekri was writing when the Muslim rulers of North Africa were still struggling to conquer more lands southwards in the parts of West Africa that was known in history as Western Sudan where economic interests were high, especially the control of trade routes. The lucrative articles of trade included gold, salt, ivory and spices. In El Bekri’s accounts the capital of Ghana fell in 1076 to the Almoravid leader, Abu Bakr. Moreover, El Bekri wrote that:

This capital had two cities six miles apart, while the spaces between were also covered with dwellings. In the first of these cities was the king’s residence, “a fortress and several rounded huts with rounded rooves, all being enclosed by a wall.” The second, which also had a dozen mosques, was a merchant city of Muslims. (Davidson 1970: 85)

We also get a glimpse of life and protocols in the king’s court from El Bekri’s accounts in a scene that reads like a cinematic stage. He writes that:

When he [the king] gives audience to his people, to listen to their complaints and set them to rights, he sits in a pavilion around which stands his horses caparisoned in cloth of gold; behind him stands ten pages holding shields and gold-mounted swords; and on his right hand are the sons of the princes of his empire, splendidly clad and with gold plaited into their hair … The beginning of an audience is announced by the beating of a kind of drum which they call deba, made of a long piece of hollowed wood. (Davidson 1970: 85)

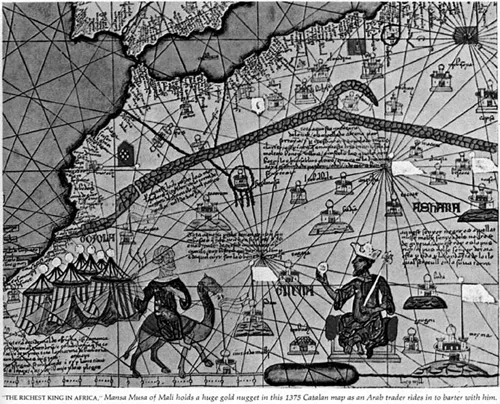

1.1 Abraham Cresques, map showing Emperor of Mali with his orb and an Arab Caravan Trader moving towards him, c.1375. Art work in public domain

Although El Bekri’s narrative of the ancient Kingdom of Ghana came from the distant middle ages, his suggestions on the wealth of the ancient Kingdom of Ghana were corroborated by the knowledge of the succeeding empire of Mali in the region. Davidson (1966: 198, 1970: 72) also writes about the 1375 Catalan Map of Africa, believed to be prepared by Abraham Cresques, showing cities beyond the Atlas Mountains and identifying certain important trading centers along the Niger River and elsewhere including “Tenbuck (Timbuktu), Ciutat de Mali, Geugeu (Gao), and Tagaza; all these, amid a host of others, would henceforth tease the interests and imagination of Europe until the earliest travelers, centuries after, could reach them at last”.

This map is detailed in its visual descriptions of places, people, wealth and activities, with King Mansa Musa seated in the middle of the map holding a golden orb and a staff of power. Bovill (1968) writes that the inscription next to him describes Musa as the King of the Negroes and the richest man in the world. Several centuries later, when the great explorers pioneered intercontinental sea routes around Africa to Asia and from Europe to the Americas, the narratives we received from many of them did not mention cities where buildings were made of asbestos, cement, zinc and aluminum, plastic, plywood, clay, sticks, thatched roof, and other natural materials like the ones built by urban non-trained architects whose works clearly derived from the modern industrial age. We neither find descriptions of such variedly built structures and settlements in African coasts in the compilation of early explorers by the London based publisher, Richardson (1789), about the famous travel of Bartholomew Dias from 1487 to 1488, nor his successor Vasco de Gama who sailed around the Cape of Good Hope during his travel to India from 1497 to 1498. Neither can we find descriptions of such urban environments in the writing of the Dutch explorer Olfert Dapper (1668) who prepared several maps and illustrations for his book, nor in the writings of William Bosman (1704) who spent time in West Africa. Dapper’s illustrations of a city in Morocco demonstrate the abundance of structures that were made of sun-baked bricks and stones that represent vernacular structures still found today in several traditional Moroccan Atlas settings. His illustration of the Oba (king) of Benin in a royal parade shows urban background images we can corroborate in bronze and brass plaques of Benin that predate that era. Buildings with high pitched stipples surmounted by large bronze sculptures of eagles and pythons that are as long as 12 feet running down the middle of the roof of the stipple with head facing the ground can be seen in the fore and the backgrounds of the illustrations.

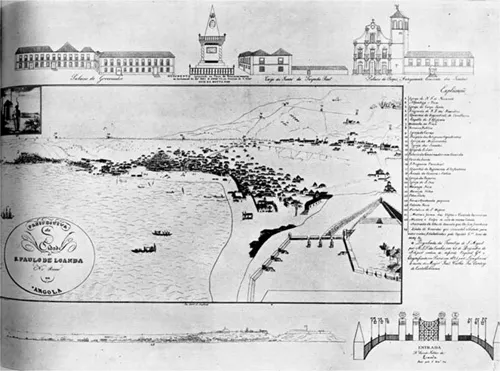

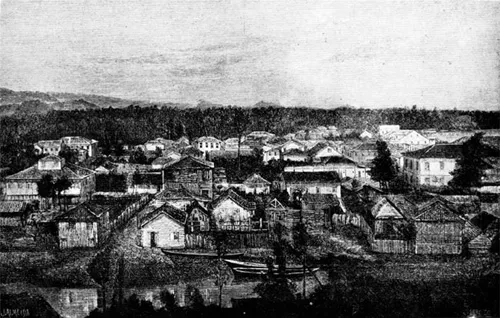

While the bodies of the bronze pythons on the stipples of the buildings have not survived, several heads in Museums in Berlin and Leipzig, Germany, corroborate Dapper’s illustrations. Moreover, an illustration of Lovango, an early Portuguese planned settlement now present day Loanda, Angola, shows that well-built structures and thatched buildings stood side-by-side.

Some of the buildings were built with stone and timber. Subsequent descriptions of cities of the Western Sudan by Mongo Park (1771–1806), Hugh Clapperton (1788–1827), Rene Callie (1824–1828), and Felix Dubois (1896) do not contain structures made of materials that were manufactured in factories or those obtained from the environment. A Felix Dubois description of Timbucktoo was nostalgic and historical; he made several sketches of the cityscapes and of buildings as well as people and how they used their spaces. Yet we find no account of structures built with materials that were manufactured in factories, or of natural materials.

Africa is not the only continent where early explorers recorded forms of settlements. Portuguese explorers’ documentations of the environments they saw in Asia and Asia Minor (parts of the world we now know as the Middle East), and Latin America, especially Brazil, did not mention settlements where building materials manufactured in factories were juxtaposed with materials that were locally resourced. Luis Silveira’s Ensaio de Iconografia das Cidades Portuguesas do Ultramar (Iconographic essays on Portuguese overseas towns), is probably the most complete in terms of visual documentation and the most ambitious despite the fact the large four-volume folios were compiled in the middle of the twentieth century, c.1950. Silveira drew from original travelers’ documents which date from the fifteenth century and through the twentieth century when Portuguese urban colonial settlements were being challenged in Africa. Volume One of Silveira’s documentation focuses on Morocco and the archipelago islands of Madeira and the Azores. In Volume Two, Silveira catalogued Portuguese settlements in parts he describes as “Africa Occidental” and “Africa Oriental.” Volume Three describes Portuguese settlements in Near and Far East, while Volume Four focuses primarily on Brazil.

1.2 Bronze head of a python reminiscent of those illustrated by Dapper in his portrayal of the royal buildings in Benin. Photo by the author

1.3 An illustration of Portuguese settlement in Loanda, Angola. Work in public domain

1.4 Sketch of Portuguese settlement in Loanda, Angola where different well-built structures stood next to thatched structures. Work in public domain

The Portuguese settlements described by Silveira share certain commonalities. The earliest ones were located on major Islands, or along the coastal towns in Africa, India, and Latin America, and they were first and foremost port settlements. Some were located on existing fishing ports or near where they could have access to supplies for the ships as they called on one port and another. Portuguese-built settlements could be easily distinguished from local built settlements due to the huge financial investment by the King of Portugal and wealthy investors who had stakes in the emerging trade and explorations. Portuguese main structures were state-sponsored; they were not constructed like shantytowns although they eventually mushroomed in the vicinities when individuals seeking opportunities and trade with the foreigners began to pitch camps around the settlements. The most prominent, earliest and largest was established in West Africa. Now in present-day Ghana, Fort Elmina (Fort of Mine of Mina) was established in 1482 in order for the Portuguese to take advantage of trade, especially gold. The differences between the architecture of the fortress and t...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Contributors' Biography

- Preface

- Introduction Keeping the Mission of Modern Architecture in Focus

- Part I Context(s) and Theoretical Underpinnings

- Part II Sustainable Shared Spaces and Experiences of Modernity

- Part III Politics and Urban Regulations: Demolished and Refurbished Neighborhoods

- Conclusion

- Index