![]()

Part I

Theories

![]()

1 Globalization and changing conceptions of Colombia’s Llanos frontier since 19801

Jane M. Rausch

The Llanos are an extensive region of seasonally-flooded tropical plains consisting of grasslands and forests shared by Venezuela and Colombia. Artificially divided by the international boundary between the two countries, they in fact comprise a single ecosystem that stretches in a northeast direction from the foothills of the Colombian Andean Mountains and along the course of the Orinoco River nearly to its delta in the Atlantic Ocean. Limited by the Andes in the west, the Venezuelan Coastal Range in the north, and the Amazonian wilderness in the south, the region covers some 451,474 square kilometers. Around 39 percent (176,359 sq. km.) lies within Colombia accounting for 17 percent of that county’s territory, while 61 percent (275,115 sq. km.) make up 31.2 percent of Venezuela’s territory (Rivas et al. 2002, 265). During the dry season (November to April) the land is parched and the grass brown, brittle, and inedible while during the rainy season much of the area is inundated. Notwithstanding this harsh climate, the region teems with wildlife, harboring more than 100 species of mammals and over 700 species of birds. The Llanos also harbors the Orinoco crocodile, one of the most critically endangered reptiles on earth, along with other rare species including the Orinoco turtle, giant armadillo, giant otter, and several species of catfish.

Until recently geographers and historians who studied the Colombian portion of this region, known as the Llanos Orientales, have regarded it as a frontier territory, for isolated as they were by the Eastern Andean Cordillera, these tropical plains appeared to be a peripheral area of little consequence in the evolution of national history, despite the fact that towns, ranches, and missions established there have been interacting with the region’s aboriginal inhabitants since the sixteenth century. Since the 1980s, however, the rapid exploitation of petroleum in the plains by multinational companies, the arrival of thousands of migrants, and consequent urbanization have brought significant changes to the region’s demographic composition, social structure, and political dynamics. This impact of globalization has prompted some scholars to modify the concept of “frontier” when referring to the Llanos, while others prefer to regard the plains as “Orinoquia” (a trans-national region including the Llanos of Colombia and Venezuela), and still others have suggested that the area should be analyzed as an international borderland. Since each of the three approaches provides new insight, the object of this chapter is to suggest some ways twentieth-century social scientists have employed these models to analyze the role of the Llanos frontier in the shaping of the Colombian nation.

The frontier in U.S. historiography

In 1973 when I first began to study the history of the Llanos Orientales, it is perhaps not surprising that, as a young North American gringa, I chose to adopt a variation of a North American model, the Frontier Thesis proposed by Frederic Jackson Turner, as a framework interpreting my data. In 1893 Turner delivered a seminal speech entitled “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” which was to have an enormous impact on the study of U.S. history. In this address Turner suggested that a major theme in the history of the United States was a “moving frontier” which he defined as the line between “civilization and barbarism” (Billington 1973, 18). He argued first, that this line moved westward across the continent offering “free land” to North Americans seeking to make a new life, and second, that their struggle for survival required them to rebuild their societies afresh. In short Turner maintained that the two social processes of settling and surviving on free frontier lands shaped American character and institutions, and that “to the frontier, the American intellect owes its striking characteristics of inventiveness, practicality, inquisitiveness, restlessness, optimism and individualism” (Turner cited by Weber and Rausch 1994).

For much of the twentieth century U.S. scholars regarded the Turner Thesis as the single most useful concept for understanding the distinctive features of North American civilization, and it was not until the 1980s, that a new generation of historians emerged who were willing to challenge the idea of “frontier” as a useful category of analysis (Weber and Rausch 1994, xxxii). Taking into account their earlier numerous (and valid) objections, John Mack Faragher in 1992 concluded that “Turner’s thesis long ago found its way onto the trash heap of historical interpretations” (Faragher 1992, 30), but others such as Martin Ridge and Richard Slatta argued that “reports of the trash heap may be premature.” They pointed out that Turner’s thesis continues to attract those who find it useful in modified form, and that the frontier remains a compelling heuristic device used even by Turner’s detractors (Ridge 1991, 76). In his book, Comparing Cowboys and Frontiers: New Perspectives on the History of the Americas (1997), Richard Slatta suggests that, revisionist historians notwithstanding, the frontier as an analytical construct remains important in framing the history of the Western Hemisphere. He writes, “I believe it is counterproductive to bury the concept of frontier simply because Turner’s formulation has proved incorrect.” In fact, the study of frontiers “has been enriched by framing them within the process of incorporation . . . Frontier social changes and interaction need more probing. Even if we acquiesce to burying Turner, we should demur from burying the concept of the frontier with him” (Slatta 1997, 131).

Frontier historiography and the Colombian Llanos

Before 1970 the scholars who attempted to apply Turner’s view of the frontier to the Colombian Llanos were North American geographers. They noted that while the Spanish conquistadors quickly incorporated into their New World Empire the Amerindians living in the high Andes and along the coast, their impetus was checked by the barrier posed by the Eastern Andean Cordillera, the inhospitable jungles of the Amazon Basin, and the equally unattractive tropical plains broken up by the Orinoco River. Blocked by a combination of geographic obstacles, deadly climate, native resistance, and lack of material incentives, the Spanish contented themselves with extending nominal control over thousands of miles of unexplored tropical wilderness. These geographers observed that although settlers did move into the tropical plains as early as the seventeenth century, they quickly found themselves isolated from the altiplano (highlands) by the rugged Andes and were forced to resign themselves to a self-contained existence based on cattle ranching and subsistence crops. Unlike the situation in the U.S. West, in the Llanos during the next three centuries there was little expansion eastward, thus giving rise to the notion of a “permanent” as opposed to a moving frontier (Bowman 1931, 84; Brunnschweiler 1972, 88).

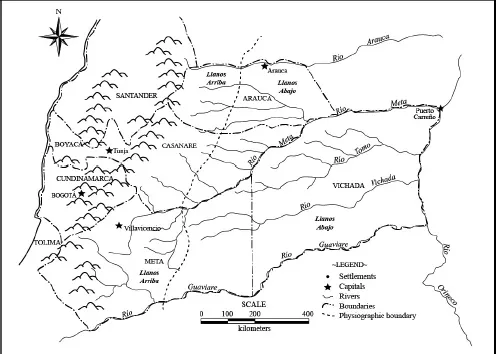

To test the concept of a “permanent frontier,” between 1984 and 2013 I wrote four books that traced the history of the Colombian Llanos (a region which includes the present day departments of Meta, Casanare, Arauca, and Vichada) from the Spanish conquest to the present. Covering developments up to 1950, the first three volumes largely substantiated that the frontier line established by the seventeenth century along the edge of the Eastern Andean Cordillera, expanded eastward only slightly despite improved health conditions and technology that made the topical lowlands potentially more accessible by the early twentieth century.2 The settlers of plains might rightfully be called pioneers even though they had lived on farms or in villages occupied by their families for generations. The Llanos frontier with regard to Colombia’s population center in the Andes was characterized by its immobility.

This immobility, I argued, did not keep the region from participating in the gradual evolution of the nation. Although traditional histories ignore its role, it is certain that, in the colonial period, Casanare was a major supplier of cattle to Boyacá and that some of its inhabitants took an active part in the Comunero Revolt of 1781. Llaneros were a decisive force in the War of Independence and the War of the Thousand Days. In the 1930s, President Alfonso López Pumarejo signaled out the Intendencia del Meta as a key area for development during his so-called Revolución en Marcha. Much of the fighting during La Violencia (1948–1964) took place in Meta, Casanare, and Arauca, and one needs only to read José Eustacio Rivera’s La vorágine or Eduardo Carranza’s poems to appreciate the contribution of the Llanos to Colombian literature (Rausch 1988, 32–40).3

The transformation of the Llanos in the twentieth century

The last decades of the twentieth century witnessed a sharp rise in national awareness of the significance of the Llanos. The Department of Meta was of special interest for, as a result of improvements in the Bogotá–Villavicencio highway, it had become a major supplier of cattle and agricultural commodities to the vast market in Cundinamarca. Although the Violencia compelled at least 6,000 people to abandon the plains between 1948 and 1953, they were soon replaced by the arrival of 16,000 new emigrants fleeing violence in other parts of Colombia (Ojeda Ojeda 2000, 187, 205). During the National Front (1958–1974) improvements in health measures and communication, the availability of public lands and the organization of colonization programs prompted thousands of settlers to move out to the Llanos with the hope of beginning a new life for their families. By 1993 the population of the four departments was 1,077,711 or nearly double the number counted in 1973. Although this figure was less than one percent of Colombia’s total population of 40 million, in demography as well as economy, the region had emerged as one of the fastest growing segments of the country (Iriarte Núñez 1999, 134).

Frontier historiography and the Llanos since 1980

After 1980 the increasing importance of the Llanos thanks to the petroleum boom, and the activities of drug cartels, guerrilla groups, and paramilitaries has prompted some Colombian scholars (all either born in the Llanos or with close ties to the plains) to offer new conceptual models of the region. Five of them concentrating primarily on Meta have employed variations of the Turnerian definition of frontier to interpret the recent history of the department. Others have suggested that all four departments should be regarded as Orinoquia i.e. as a “region” that transcends national boundaries to encompass the Llanos of Venezuela as well as those of Colombia, while a third group, focusing on Arauca and Vichada propose exploring Llanos history from the standpoint of an international frontier or borderland with Venezuela (see Figure 1.1).

Neo-Turnerians

The first five scholars (who I regard as “neo-Turnerians”) agree on essential points but diverge in their emphasis. In his 1997 book, Un pueblo de frontera: Villavicencio 1840–1940, historian Miguel García Bustamante challenged the traditional view that the Llanos formed a permanent frontier by pointing out that, notwithstanding the geographical difficulty of intercourse between them, the proximity of Villavicencio to Bogotá had from the seventeenth century involved a reciprocity characterized by unequal relations since Villavicencio was dependent politically on Bogotá, and its export economy of cattle and food commodities was directed almost exclusively to the national capital (García Bustamante 1997, 11). In 2003 García Bustamente refined his analysis further to suggest that the Llanos region per se consisted of two different frontiers. The piedmont area or Llanos arriba was a frontera provisoria or temporary frontier characterized by constant interaction with the highlands, while the grasslands east and north of the piedmont or the Llanos abajo remained a permanent frontier where development took place much more slowly (García Bustamante 2003, 40–41).

Anthropologist Nancy Espinel Riveros in her books has emphasized that Villavicencio is a frontier city from the standpoint of the east as well as the west, for just as it receives a constant stream of migrants from Colombia’s highland departments, it continues to be the western terminal for cattle regularly driven from the northern and far eastern plains of Casanare and Arauca to be sold eventually in Bogotá. Since its founding Villavicencio has been a mixture of two distinct cultures—Andean and Llanero—a duality that persists to this day. In her view the city has been converted into a human “crucible” in which are mixed both these distinctive traditions (Espinel Riveros 1997, 201–202).

Describing the same phenomenon of a dual plains frontier, economist Alberto Baquero Nariño takes a dependency point of view in El caso llanero: Villavicencio, but he substitutes the term frontera interior for Bustamante’s frontera provisora. He suggests that Villavicencio exhibits the characteristics of a frontera interior because “immigrants pass through the city with little desire to settle in it; residency is impermanent; there is little substantial financial investment in the region, and the inhabitants do not display a sense of civic concern” (Baquero Nariño, 1990, 32–34). Still worse, from Baquero’s point of view, is that, although Villavicencio is the center of Llanero economy, that economy since 1950 has been characterized by “savage capitalism” by which he means that it is dominated by “continual export of economic products and the absence of a genuine agro-industrial economy that could generate wealth for the region.” The transport of cattle on the hoof for Bogotá and the predominance of rice and African palm oil produced by large corporations are characteristics of an extractive economy of very little regional value and minimal generation of employment (Baquero Nariño 1990, 69).

Writing in 1990 Baquero Nariño does not include the impact of the petroleum boom in his analysis, but it is evident from publications by historian Reinaldo Barbosa Estera that, first in Arauca and then in Casanare and Meta, oil exploitation has been similarly skewed to profit multinational corporations rather than the economic growth of the Llanos. The plains have a proven reserve of 500 million barrels of oil, but in those locations where it has been extracted, petroleum taxes have not fulfilled the promise of generating expected local revenues. Barbosa further asserts that the decision by the Ministerio de Minas y Energía to hand over the pipelines to multinational companies for 99 years “can be seen as a rebirth of colonialism” (Barbosa Estera 1998, 164–168).

In contrast to the previous four scholars who focus attention on the Department of Meta, economist Fredy Preciado has been exploring the reasons for Casanare’s arrested development—a lack of growth that is especially striking when compared with the rapid change occurring in nearby Meta, and he offers a solution. Conceding that the exploitation of oil in Casanare has only reinforced its dependency, Preciado sug...