- 920 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

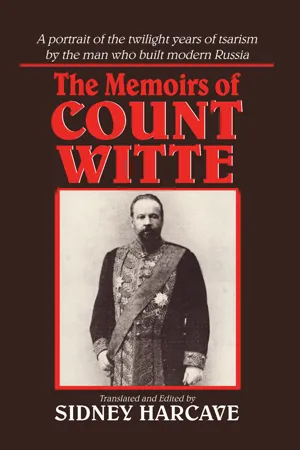

The Memoirs of Count Witte

About this book

A portrait of the twilight years of Isarism by Count Sergei Witte (1849-1915), the man who built modern Russia. Witte presents incisive and often piquant portraits of the mighty and those around them--powerful Alexander III, the weak-willed Nicholas II, and the neurasthenic Empress Alexandra, along with his own notorious cousin, Madam blavatsky, the "priestess of the occult".

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Memoirs of Count Witte by Sergei Iu Witte,Sidney Harcave in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

VOLUME I

1849–1903

I

My Family

Parentage

I was born in Tiflis in 1849 and am now sixty-two.1 My father, Julius Fedorovich Witte, a member of the nobility (the dvorianstvo)2 of Pskov province, was born a Lutheran, in the Baltic provinces. His ancestors were Dutch who had settled in the Baltic provinces when they still belonged to Sweden.3 After graduating from the University of Dorpat,4 he studied agriculture and mining in Prussia. It was as an agricultural expert that he went to Saratov, where he fell in love with my mother, Catherine Andreevna Fadeeva. She was one of four children of the governor of Saratov province, Andrei Mikhailovich Fadeev, and Princess Helen Pavlovna Fadeeva, née Dolgorukaia, the last of the senior branch of the Dolgo-rukii princes; she was descended from Gregory Dolgorukii, a senator during the reign of Peter I, the brother of the famous Jacob Fedorovich Dolgorukii.

My grandparents were married when they were very young. Where, I do not know, but I know that my grandmother’s relatives belonged to the nobility of Penza province. When they married, my grandmother’s father, Paul Vasilevich Dolgorukii, blessed them with an ancient cross that, according to family tradition, had belonged to Michael of Chernigov. It is said that Michael died a martyr’s death (for which he was canonized) for refusing to bow before the idols carried by a Tatar khan who was marching on Moscow. It is further said that, as he went to his death, he entrusted a cross to some boyars with instructions that it be given to his. children; this cross, according to tradition, was handed down from father to son in the senior Dolgorukii line.*

Grandfather Fadeev was under his wife’s moral domination, so that, in fact, she was the head of the family.

For her time she was an exceptionally well-educated woman. She was a great nature lover and put together a large collection of Caucasian flora, which her heirs were to give to Novorossiisk University. It was she who taught my brothers and me to read and write and who instilled in us the fundamentals of the Orthodox faith. She was already paralyzed by the time I was a boy, and I always remember her as being seated.

The eldest of their four children, Helen, was fairly well known in the Belinsky era as a writer, under the pseudonym of “Zinaida R.” My mother was the second of the four. The third, Nadezhda, is about eighty-three, and lives in Odessa with my surviving sister. The fourth was the eminent writer on military themes, General Rostislav Fadeev.

My grandparents were ardent members of the Orthodox faith (genuinely Orthodox and not Orthodox in the Black Hundreds sense of the word) and would not hear of their daughter marrying out of the faith. So my father was converted to Orthodoxy, either before marrying or shortly thereafter. Because my father became an integral part of the Fadeev family and did not retain close ties with the Witte family, and because he enjoyed several decades of marital bliss with my mother, he became completely Orthodox in spirit.

When grandfather accepted a post in the Chief Administration of the Caucasian Viceroyalty5 and moved to Tiflis [in 1846], my parents joined the Fadeevs in their move. In time father was to become the director of the Department of State Domains. This was at a time when few were eager to take civilian posts, even very high ones, in the Caucasus, because it was an isolated region, ablaze with uprising, where the mountain passes were still held by hostile tribes, a region marked by frequent conflicts with the Turks. However, military men and others who liked to be where there was fighting were attracted to the Caucasus. Perhaps my grandparents were eager to go there for that reason.

The Wittes and the Fadeevs shared the same household, which was one of the largest and most hospitable in Tiflis. It was located on a side street, the name of which I do not recall, that ran from Golovinskii Prospekt to Mount Davidovskaia. Grandfather lived on a lordly scale. Even though I was very young then, I can clearly recall that just the household serfs (most of them Dolgorukii serfs) numbered eighty-four.

The Witte Children

I was one of five children, three boys and two girls. The oldest was Alexander [b. 1844].6 He studied at the Moscow Cadet Corps and spent almost all of his career with the Nizhegorodskii Dragoons, who still sing songs about the brave Major Witte, whose eyes radiated kindness.

Alexander was rather stout and awkward, of average height, average intelligence, average education. But he possessed a remarkably fine soul. He was a very sympathetic, good-natured person. All of his brother officers—even those with whom he occasionally quarreled—loved him.

Sometime before the Turkish War [1877–78] Alexander killed Westmann, an officer in the Severskii Regiment, in a duel. (Westmann’s father served as assistant minister of foreign affairs under Gorchakov.) At the time of the duel both Alexander’s and Westmann’s regiments were stationed in Piatogorsk, a popular spa. The duel arose over a young lady whose family was visiting Piatogorsk and with which Alexander was on close terms. Westmann was in love with the young lady, and although he was handsome and Alexander was not, he saw him as a rival.

According to Alexander, the incident that led to the duel took place during a ball at the officers’ club, of which he was chairman. He had been sitting at a table with the young lady, when he was called away on business. On his return he found Westmann sitting in his chair, but now there was an additional chair beside the young woman, which she had evidently ordered to be placed there for him to sit in when he returned. After Alexander sat down, Westmann asked if he had done so to overhear their conversation. Alexander replied that he didn’t think there was anything to overhear and that, in any case, he was quite ready to leave. West-mann then called him a scoundrel.

The next day Alexander sent two of his fellow officers to inform Westmann that he, Alexander, knowing that Westmann had been drunk when he had insulted him, would take no further action if he apologized to him before the officers. Westmann refused, saying that he had intended his remark to produce the usual result. Alexander thereupon issued a challenge to a duel, which was accepted.

The two agreed that the duel would continue until one of them was killed or so severely wounded that he could not hold his pistol. The first signal to fire was given when they were eighty paces apart. Alexander told me (and this was later confirmed at his trial) that at the first signal he fired into the air, but that Westmann’s shot just missed his ear. When my brother sent his seconds to see if Westmann was ready to apologize, Westmann refused. Each then advanced ten paces and fired on signal: again Alexander fired into the air; Westmann’s shot grazed his other ear. By this time my brother was very angry, but once more he sent his seconds to ask Westmann to apologize. Again a refusal. They advanced once more and fired on signal. Westmann’s shot was close; Alexander’s was fatal.

My brother was then tried and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, but, as I recall, he had served no more than two months when war with Turkey broke out and he was released on the order of the Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich, viceroy of the Caucasus, so that he could join his regiment in combat.

Alexander distinguished himself during the war, in which he first commanded a squadron, then a battalion. Best known among his exploits was one that took place near Kars. General Loris-Melikov, the corps commander, sent him on a reconnaissance mission, with two Cossack companies under him. Using a map provided by the General Staff, they were to proceed toward Kars by one route and return by another. En route they suddenly encountered several Turkish battalions. Since Alexander’s orders were to proceed on that route, he ordered his men to attack. They broke through, with few casualties, and galloped on till they came to a deep ravine not shown on their map. There was no way to go around the ravine. Faced with a choice of riding into it, which would have meant certain death, or turning around and attacking the Turks, who had just arrived with reinforcements, he ordered his men to attack. Again they were successful, but this time at the cost of heavy casualties. Throughout the engagement Alexander held on to his unit’s flag.

According to regulations Alexander should have received the St. George7 for his courage under fire, but if he had it would have come out that the officers of the General Staff had prepared a faulty map and it would have been necessary to try them. So Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich, who liked my brother, summoned him and told him they would have to “pretend that the whole episode had never occurred.” However, amends were made after the war, when the facts could be revealed. At the first St. George celebration after the war, which my brother attended with other officers from the Caucasus, Emperor Alexander II (who had been told of the facts by the Grand Duke) took off his own small St. George decoration and gave it to my brother, saying that he had long ago earned it.

Despite the constant dangers to which he had been exposed, Alexander had gone unscathed until the very end of the war, when he suffered a concussion from a Turkish bomb and was presumed to be dead when he was taken to a hospital. In fact the Grand Duke sent a telegram of condolence to my mother. But Alexander regained consciousness in the hospital and was able to leave it soon. Unfortunately, the concussion left him unable to open his eyes in daylight, and he had to sit with his eyes shut during the daylight hours. I consulted the finest doctors about his condition and was warned that he could die of a stroke at any time.

Because of his disability he was given no more than the command of a reserve cavalry cadre stationed in Rostov. One sad day I received a telegram from Dr. Pisarenko, the unit’s doctor, informing me that my brother had died in his sleep, of a stroke.

I loved Alexander more than I did any other member of my family.

We often talked about fighting. Alexander told me not to believe those who said they did not experience fear before going into battle: everyone was afraid, at least until the fighting started. That, he said, was his experience. Before the battle he would be anxious, but once the fighting began he would slash away at the enemy with less feeling than if they were sheep. General Skobelev, whom I knew, had much the same experience: he was always frightened before the battle, but once he took his place before his men and the shooting began, his fears would vanish.

I experienced similar feelings during the six months that I was premier when I was in constant danger. I would be warned to remain at home for a few days or not to go to this place or that, but I ignored the warnings and when I was advised to avail myself of a guard I would not. Yet I must admit that many a night I went to bed frightened and shaking, thinking of the next morning when I would have to go downstairs, get into my carriage, and go somewhere where there would be a crowd. But as soon as I would take my seat in the carriage and it would begin to roll my fears would vanish and I would feel as calm as I do now, dictating these lines. It was at such times that I truly understood the feelings about which my brother had spoken.

My other brother, Boris [my elder by a year], did not distinguish himself. He graduated from the faculty of jurisprudence of Novorossiisk University and was chairman of the Odessa Superior Court at the time of his death.

My two sisters, Olga and Sophia, were younger than I. They were very close and lived most of their years together, in Odessa. Sophia, the younger sister, who contracted tuberculosis, is alive but is very ill. Olga, who nursed her, contracted the disease and died of it, two years ago. Those of the Fadeev family who are still alive are I, Sophia, and my aged aunt Nadezhda, who lives with Sophia.

I was my grandfather’s favorite and Alexander my grandmother’s. The family treated me kindly but, on the whole, with indifference. Boris was my parents’ favorite and was more spoiled than the rest of us. Olga, too, was favored by my parents, being their first daughter after three sons. Sophia, although treated affectionately by everyone, was not spoiled.

I clearly remember a few events from my early childhood. I remember that when I was a few months old and there was an epidemic in Tiflis, my father took me in his arms and mounted his horse, on which we rode to a place outside the city. My mother and my sisters would laugh at me when I spoke of this recollection, saying that I could not possibly have remembered this incident, but my old wet nurse, whom I saw only a week ago (she lives with my sister in Odessa, where I go on holidays), thinks that I am not imagining it.

I recall another episode from my very early years. I was in a room with my nanny when first my mother, then my grandfather, my grandmother, and my aunt came into the room sobbing over the news of the death of Emperor Nicholas Pavlovich. This made a strong impression on me; one can sob like this only when one has lost someone very close. My family was always extremely monarchist, and this trait is part of my inheritance.

The Zhelikhovskiis

My mother’s oldest sister, Helen, who married Colonel Peter Hahn, died at an early age leaving a son and two daughters, Helen and Vera. The son was a nonentity; he was a justice of the peace in Stavropol at the time of his death. Helen and Vera were taken into my grandfather’s home after their mother’s death. Shortly thereafter Helen married Blavatskii, the lieutenant-governor of Erivan, and Vera married Iakhontov, a landowner in the province of Pskov.

After Vera’s husband died, she returned to the Fadeev household in Tiflis. There she fell in love with Zhelikhovskii, a local gimnaziia teacher. The Fadeevs, who were not devoid of a kind of boyar arrogance, naturally would not hear of her marrying the man. So she fled home, married him, and never again set foot in the Fadeev household. It was only after the death of my grandparents that my parents began to receive the Zhelikhovskiis.

Vera wrote books for young people. To this day mothers talk to me about her books and express regret that she is gone and that books suitable for young people are no longer written. I must confess that I have never read any of her books.

She is survived by two sons and three daughters. One son is a colonel in a dragoon regiment. The eldest daughter married an American journalist named Johnson; when I was in the United States they called on me.

The other daughters live in Odessa; one of them married a seventy-year-old corps commander a few weeks ago. They are the kind of women my sisters would not receive, nor would I. My sister Sophia calls them disgraceful types. Even though I am not especially censorious about morals I consider them contemptible: they may in fact be Okhrana [political police] agents, and they were on very good terms with Tolmachev, the prefect of Odessa.

Blavatskaia

Now I want to dwell on the personality of Vera’s sister and my cousin, Helen Petrovna Blavatskaia [Madame Blavatsky], who for a time made quite a stir as a Theosophist and writer.8

I have no recollection of her in the years just following her marriage [1848], but from stories I later heard at home I know that she soon abandoned her husband and returned to the Fadeev household. No sooner had she appeared there than Grandfather Fadeev sent her packing to her father, who then held a military command somewhere near Petersburg. Since there were no railroads then in the Caucasus, he sent her in a hired coach-and-four, accompanied by a steward chosen for his reliability and three other servants. They were to go by coach to Poti and from there to a southern Russian port, and from there proceed to her father’s residence.

When they arrive...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction by Sidney Harcave

- Countess Witte’s Foreword

- I. V. Hessen’s Introduction: Excerpt

- A. L. Sidorov’s Introduction: Excerpts

- Volume I 1849-1903

- Volume II 1903–1906

- Volume III

- Editor's Notes

- Sources

- Bibliography

- Name Index

- Subject Index