![]()

Chapter 1

Of Artifacts and Organs: World Telegraph Cables and Ernst Kapp’s Philosophy of Technology

Frank Hartmann

The Nascence of Global Media

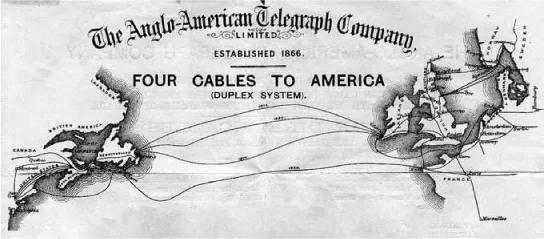

By 1850 the electric telegraph had spread all over England, Europe and the populated areas of North America. Now began the ambitious endeavor of “wiring the abyss,” to put it in the words of science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke (1992). This was to use submarine telegraphy first to connect England with the continent, and second the two continents of Europe and North America—or Newfoundland with Ireland, to be exact. In fact there was no abyss at all. The idea of laying a transatlantic cable was based on recent oceanographic findings showing: “There is at the bottom of the sea, between Cape Race in Newfoundland and Cape Clear in Ireland, a remarkable steppe, which is already known as the telegraphic plateau” (Maury 1855, 317). The oceanic submarine cables, whose successful functioning required much trial and error from the engineers side, not only meant the generation of enormous revenue, but also laid foundation for the first global telecommunications hegemony of the British Empire (Hugill 1999).

The structure of the new global telecommunications order was based on old trade routes with connections and nodes at geopolitically important locations, with London eventually as the logical center of the colonial world. As this new kind of technology brought the world closer together than as never before, it created the new task of finding international standards and technical codes of exchange. This led to the first International Telegraphy Congress in Paris in 1865. But even in 1851 with the emergence of international World fairs such as the “Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations” in the Crystal Palace in London, new technologies like photography and telegraphy were being popularized through demonstrations in this new environment, though not Charles Babbage’s new calculating machines, much to the discomfort of their inventor who reported on the Great Crystal Palace Exhibition (Babbage 1851).

In these years of building an international network of communication cables, the notion of “communication” itself changed significantly from personal, direct communications to its modern, mediated form. Tele-technologies now were conceived of as extensions of mankind and as forming an environment for a culture of modern fluid aesthetics. We see this stated by Charles H. Cooley, the first sociologist of communication:

By communication is here meant the mechanism through which human relations exist and develop—all the symbols of the mind, together with the means of conveying them through space and preserving them in time. It includes the expression of the face, attitude and gesture, the tones of the voice, words, writing, printing, railways, telegraphs, telephones, and whatever else may be the latest achievement in the conquest of space and time (Cooley 1909, 61).

What would this new infrastructure mean for human communication and thought? Could it be related to the new and much discussed theory of evolution by Charles Darwin? Was there some kind of co-evolutionary relationship between technology and biology? Could technology fit into a process of forming an intelligent network for which later the term World Brain would be employed?

The aggregation of technologically mediated experience in the nineteenth century came as a challenge to the philosophy of mind that had originated with Immanuel Kant and Georg W.F. Hegel just a few decades before. In 1855, a report in Scientific American could state triumphantly: “English telegraph engineers deserve great credit for the boldness and enterprise they have exhibited in laying down so many ocean lines. They have made the ocean a highway of thought.”1 However, in the mainstream academic traditions of the times there was little interest in reflecting theoretically on the epistemological impact of the new technology of the telegraph with its capacity to build a “highway of thought” all around the world.

Unlike most academics, however, German geographer and philosopher, Ernst Kapp, had indeed been reflecting on the shift towards a global form of communication through “universal telegraphic” technology for which he used the term Weltcommunication. Moving away from his orientation as a left-wing Hegelian, he created a form of materialistic philosophy for which he first used the term Philosophie der Technik (Philosophy of Technology). He proposed that there was a specific relationship between biology and technology which he called Organprojektion (organ projection), thus anticipating by about a century the notion of media technology as “extensions of man” (cf. McLuhan 1964).

Biographical Sketch

Ernst Kapp (1808–1896) had an unusual career. After academic studies in philology, he took up a post teaching at the gymnasium in Minden where he became fascinated by the new science of geography of Alexander von Humboldt and Carl Ritter. It was especially Ritter who influenced Kapp to think of geography in a physiological way in which elements of the earth were considered to be like inter-related organs. He developed these ideas in his two volume Vergleichende allgemeine Erdkunde which he published in 1845. This General Comparative Geography anticipated “what might today be called an environmental philosophy” (Mitcham 1994, 21).

Kapp was less an academic thinker than an unruly intellectual and libertine. In 1849 he published a treatise against political despotism which, following the revolutions of 1848 in the German states, made him an inconvenience to the authorities. He was prosecuted for sedition. As a political dissenter, he sought refuge in the United States where he joined a German pioneer settlement in central Texas. There he built a house and worked as a farmer. Nearby he also began to operate a spa called Badenthal where he offered “Dr. Ernst Kapp’s Water-Cure.” This involved hydropathy treatment and gymnastic exercises.2 To understand Kapp’s philosophy of technology, Carl Mitcham stresses the fact that during his years in Texas, he “led a life of close engagement with tools and machinery.” In 1865 he paid a visit to Germany again. But suffering from bad health, on medical advice he decided against traveling back to Texas and died in 1896 in Düsseldorf.

After his arrival in Germany Kapp had taken up his academic interests again. “He revised his philosophical geography and then undertook, through reflection on his frontier experience, to formulate a philosophy of technology in which tools and weapons are understood as different kinds of organ projections” (Mitcham 1994, 23). The outcome of his studies was published 1877 in Germany as Grundlinien einer Philosophie der Technik. Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Cultur aus neuen Gesichtspunkten [Fundamentals of a philosophy of technology; The genesis of culture from a new perspective].3 As the subtitle indicates, this philosophical approach to technology tackled the origins of culture in a new way. What Kapp proposed was the concept of a relationship between biology and technology in which the latter was discussed as a bold yet unconscious externalization of human nature which gave rise to culture and civilization in general.

Technology as New Culture

As mentioned above, this philosophy of technology was published only a decade after the transatlantic cable came into full operation. The submarine lines had not only changed international relations, but they had also created a world of telecommunications that changed the way in which human beings experienced their existence. We see in this that the information society was already beginning to emerge and mature.

Figure 1.1 1880: Anglo-American Telegraph Company North Atlantic map4

Some decades before the advent of this technological phenomenon, Johann Gottfried Herder had published his Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit [Outline of a Philosophical History of Mankind, 1784–1791]. In this work he suggested that mankind was still a project in the making, subject to underlying organizational and existential changes. But while he mentioned the role of arts and crafts in the histories of different peoples, it was not until the mid-19th century with the rise of new media technologies, such as photography, sound recording and the electric telegraph that human cognition and the idea of communication itself began to change: “The far could now speak to the near, and the dead could now speak to the living” (Peters 1999, 138).

Thus technologically-induced change led to new instruments which were thought of either as potentially dangerous prostheses or as auxiliary organs which help to conquer space and time. This was observed by Alexander von Humboldt in his popular Berlin Kosmos-lectures (1845–62) which Kapp quoted:

Creating new organs (tools for observing) increases the mental, often also the physical strength of humans. In its closed circuit, electricity carries thoughts and volition faster than light. Forces, the gentle powers in elemental nature, such as the tender cells of organic tissues, yet still escaping our senses, are recognized, used, and determined for higher purposes. They are aligned in the unforeseeable array of means, which draws us closer to the mastery of particular domains of nature and the lively cognition of the world as a whole (Humboldt in: Kapp 1877, 105).

Beginning with Hegel’s reflection on the technical as a kind of instrumental reason in which mind externalizes itself to form an applied system of means, the concept of technology in the continental philosophical tradition stands for the extension of subjective skills to industrial machines and apparatuses. It can be said that to free himself from the physical world, man developed master–servant relationships with one part supplying the needs of the other (cf. Hegel 1807, chapter IV). To do so—following Carl Mitcham’s interpretation—the servants

must undertake technological work, and through work realize their own inherent dignity […]. Slaves can transform the world, which is thus less noble than they are. From such realization comes the drive for technological progress that can free the slave too from the physical environment and create the idea of a new society of free and equal citizens. In the spirit of this analysis, Kapp’s history is not the necessary unfolding of [Hegel’s] Absolute Idea, but the differential record of human attempts to meet the challenges of various environments—to overcome dependence on raw nature. This requires the colonization of space (through agriculture, civil engineering, etc.) and of time (through systems of communication, from language to telegraph). The latter, in its perfected form, would constitute a ‘universal telegraphics’ linking world languages, semiotics, and inventions into a global transformation of the earth and a truly human habitat (Mitcham 1994, 22–3).

In Grundlinien, Kapp argued that the constructions of machines is not an arbitrary process but follows an unconscious process which he described as an “externalization.” Mechanical engineering displayed morphological parallels to the human organism: first, analogies of tools with body parts are obvious (e.g., a hammer as the extension of the fist); and second, mechanical systems resemble organic arrangements (e.g., the railroad system as an extension of the circulatory system and the telegraph of the nervous system). These parallels do not follow a conscious pattern and can be observed only after the fact. Engineers constructing tunnel supports probably have never seen the longitudinal cut of a femur, yet unconsciously they follow nature’s construction principles. For Kapp it was

the intrinsic relationship that arises between tools and organs, and one that is to be revealed and emphasized—although it is more one of unconscious discovery than of conscious invention—is that in the tool the human continually produces itself. Since the organ whose utility and power is to be increased is the controlling factor, the appropriate form of a tool can be derived only from that organ. A wealth of spiritual creations thus springs from hand, arm, and teeth. The bent finger becomes a hook, the hollow of the hand a bowl; in the sword, spear, oar, shovel, rake, plow, and spade one observes sundry positions of arm, hand, and fingers, the adaption of which to hunting, fishing, gardening, and fields tools is readily apparent (Kapp 1877, 44–5, transl. by Mitcham 1994, 23–4).

Kapp was thus inverting the Cartesian tradition of regarding the organic as a mere mechanism by considering mechanical artifacts as unconscious projections of organic potentiality. As mechanical tools are unconscious projections of the osteomuscular apparatus and instruments are eventually projections of human organs, the international cable networks can be explained as projections of the nervous system. The various uses of the new technologies, he believed, would lead to a morphology of cultures and rewriting cultural history would be a necessity in terms of a co-evolutionary process. Humans unconsciously apply the form and functionality of their bodies to the objects they create. They only become conscious of this post factum. “This creation of mechanisms based on organic models, and also the understanding of organisms by means of mechanical devices, as well as the accomplishment of the principles of organ projection for fulfilling the objectives of human productivity, is the thesis of this work” (Kapp 1877, Preface).

Technology and the Unconscious

This attempt to reconcile technology and biology makes Kapp a philosopher, not of industrial society, but of the nascent information age. Traces of his Grundlinien can be found in the concepts that were developed by 20th century philosophers, among others ranging from Sigmund Freud—for whom man, with the help of his “auxiliary organs,” has become “a kind of prosthetic God” (Freud 1962, 39)—to Martin Heidegger’s questions concerning technology and to Marshall McLuhan’s concept of the media as extensions of man. Also Kapp’s notion of the “universal telegraphic,” mentioned by Mitcham, invokes the idea of telecommunication networks and anticipates the world being online. At the time of the publication of the Grundlinien, telegraph networks had already developed far beyond the experimental period. Extended internationally, they were redefining geopolitics and global communications (Hugill 1999). With the maturing of the telegraph, communications boomed in administrative and business contexts. An incredible number of technical inventions and applications, to which Humboldt had earlier referred to rather hypothetically, were created in the period of the belle époque. Society changed, and as Hegel had stated earlier in his Lectures on the Philosophy of History, “the technological appears, when the necessity exists.”5

New tools and instruments ...