![]() PART I

PART I

Text/image: The Infinite Dialogue![]()

Chapter 1

What Is an Image?

Foreword

In Vermeer’s Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid (1670) in Dublin’s National Art Gallery, a woman, facing the viewer, is sitting at a table covered with a heavy red tapestry. She is holding a goose quill that she is applying to what must be a sheet of paper that her left hand holds flat while her right hand is writing away. She is totally engrossed in her activity, cut off from the rest of the world. In the background, a woman wearing a green dress and a blue apron—the maid who has just brought the note that can be seen by her mistress’s elbow—stands at the window. Looking out with her mouth open, she no longer seems to pertain to the world of the painting but to the world outside, or rather to her vision of the outside as it merges with her reverie. This painting, I suggest, may be read as an allegory of concentration and daydreaming, halfway between tension and release, since it shows creative activity as split between two characters. The mistress, bent over her letter, may be writing what her dreamy maid silently dictates, or the letter-writer may be a source of inspiration for the musing maid. Behind the two women, on the back wall, a painting within the painting stages several characters, including two naked ones, surrounding a woman holding a child. The painting has been identified as Sir Peter Lely’s The Finding of Moses, which relates a profane miracle before the sacred miracle of Incarnation. The painting explores the tension palpable in the mute dialogue between the mistress and the addressee of the letter; in the respective attitudes of the mistress and the maid, in the dichotomy between interior and exterior, visible and invisible; between the window within the painting and the painting as window; and between Lely’s painting and the subject matter of this more recent painting by Vermeer. The tension can also be felt in the black and white squares of the floor-tiles on which the characters and the décor are arranged as though on a chessboard, the game of chess being here that of perspective and representation.

In Vermeer’s Lady Writing a Letter, the text is not visible; it is the image which takes over. This process is the opposite of what I will focus on in the following pages, since we will concentrate on the opening of the image’s eye within the visible/legible text. Nonetheless, the painting suggests a story, and the infinite dialogue between the painting and the letter, between the image and the text, between inspiration and creation, finds one of its most beautiful illustrations in a work of art whose shades of green, blue, pale yellow, brown, and dark red, toned down by gray, suggests the silence of reverie, this Silence habité des maisons which, across time, inspired Matisse. Matisse’s book, the silent dweller of houses, is a response to Vermeer’s letter.

The poetic reverie triggered by the irruption of an artistic image—a painting, an engraving, or a photograph—as well as the pleasure of “mentally contemplating” an array of colors and forms, a writing of light, have guided the choice of texts which form a language together with the image, creating with it an “infinite relationship” akin to this “infinite rapport” that Foucault evokes while contemplating Velasquez’s Las Meninas. Las Meninas are the princess’s servants, just as the image is the “the servant of the text,” bringing its magic to the service of the text. Image and text are therefore inextricably related in this celebration of the eye of/in the text.

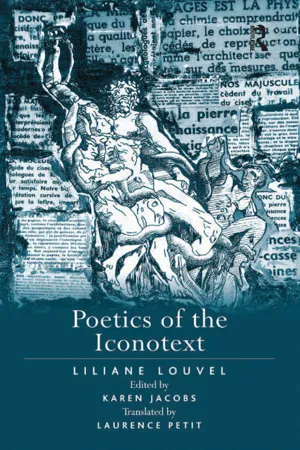

The following pages will focus on the issues raised by this infinite relationship between text and image when the image generates the text or when, as a textual inclusion, its insertion within the text interrupts the narrative flow and causes a cinematographic “freeze-frame” effect. I have deliberately chosen to exclude the works in which text and image were conceived, if not together, at least as a homogeneous work though a fertile exchange between two artists. Those are the “iconotexts” as defined by Alain Montandon,1 i.e. “inseparable entities” like those of Miro and Breton, Bazaine and Tardieu, Montebello and Saura. To this type of iconotexts could be assimilated such seminal works as William Blake’s illustrations and intricate enfolding of word within image or vice versa.2 But this would be closer to “illustration” as studied by Hillis Miller in the wake of illuminated medieval manuscripts and nineteenth-century illustrated novels “combining two kinds of signs.”3 To this tradition Vanessa Bell’s illustration of her sister’s Kew Gardens for instance would pertain. She borrowed from Blake, who knew a thing or two about word and image—as his engraving of the statue of Laocoon he chose to surround with a lacelike intricate web of words testifies to. In the same way this book will not study such occurrences of word/image conjunctions found in comic strips, graphic novels, or series. Again, these are works conceived together often by two different artists and they require a thorough, specific study.4 I will focus on such occurrences of word/image apparatus as are exemplified in fiction under the guise of images translated or converted into words or visible images included in a novel as a prop to fiction. My concern is primarily with literature including two-dimensional works of art: painting, photography, miniature, engravings … or vision-related artifacts: mirrors, optical devices, all kinds of reflection.

I will, however, retain the term “iconotext” since it illustrates perfectly the attempt to merge text and image in a pluriform fusion, as in an oxymoron. The word “iconotext” conveys the desire to bring together two irreducible objects and form a new object in a fruitful tension in which each object maintains its specificity. It is therefore a perfect word to designate the ambiguous, aporetic, and in-between object of our analysis.

Let us place this discussion under the sign of two circular forms, those of two shields, Achilles’ shield and Perseus’ shield—two mirrors laden with ancient knowledge, reflecting what is at stake in the notions of representation and myth. These figures of representation, which are still in conversation and which we will use as emblems, come together through a very old trope, ekphrasis—the inclusion of a work of art within a text—which shows and designates at the same time as it describes, thus opening the legible to the visible and suspending time. Representation can therefore be seen as an apotropaic shield protecting both the artist and the reader/viewer against death.

Let me start with an observation: there is an abundance within texts—a mode of representation traditionally related to time—of references to painting, photography, and the graphic arts: references, in other words, to visual representation. This observation shows the limitations of the old dichotomy between spatial and temporal arts. We shall also notice that some literary traditions seem to be more influenced by the visual arts, particularly by pictorial art, than other art forms such as music. This seems to be the case, for instance, with French, English, and Italian literature. German literature, deemed more “expressive,” seems to have established a stronger connection with music. Is this a matter of cultural heritage? Aristotle described the sound of the flute and of the lyre as modes of imitation. So, ut musica poesis? Or ut pictura poesis? It is not sufficient to acknowledge the overwhelming importance of iconography within narration; one must question the poetic tradition to which this gesture belongs, and therefore question the poet’s obstinacy in wanting to blend two semiotic systems which are fundamentally heterogeneous. This amounts to saying that we will need to re-open the debate on ut pictura poesis, the Sister Arts rivalry, and Da Vinci’s Paragone, in which the agon opposes two related art forms. We shall try to establish a typology of the modes of insertion of images within texts which produce iconotexts, new hybrid artifacts whose modalities need to be studied.

With the help of a sample of literary texts, I shall attempt to define the modus operandi of such images so as to propose a “poetics of the iconotext.” Rhetoric shall have its place, as though conveyed by the “figures” and “images” whose very signifiers indicate the commonality between the verbal and the visual arts. The words “figural,” “figured,” “figurative,” and “figuration” are indeed so many ways of describing modes of knowledge about the visual and the verbal arts which are inextricably linked in their relation to the world. As an example, the ambiguous status of descriptions, halfway between discourse and story, according to Benveniste’s terminology, coincides with the postmodern questioning of history as a discursive construct, as illustrated in the novels of J.M. Coetzee and Salman Rushdie.

Old myths connected to representation—such as the myths of Medusa, Orpheus, and Narcissus—will come into play as we study the visual arts, and particularly paintings, in an attempt to account for their constitutive aporia in the dialectic between seeing and being seen. In a similar manner, we shall examine the interplay of the powers of the image, the roles of figures as figuration of the real, and the strategies of reproduction, mimesis, and phenomenological experience as they combine their energies. Geometry, structures, forms: these will be so many tools to outline visible and/or discursive patterns so as to conceptualize repetition as copy, rewrite, and representation—mostly the representation of its own signifying process. It is well known that the work of art does not represent the world; it signifies the way in which it perceives and conceives of it. A work of art is mostly self-reflexive, a medium scintillating in the interstices of its appearance/disappearance, like the blinking of an eye.

The reader will have to refrain from projecting a pictorial reference onto a text by association of ideas because a particular passage reminds him/her of this or that painting. The reader would then be in the position of a counterfeiter, giving a work of art a false identity. We shall examine the modes of inscription of paintings within texts as a specific modality of the descriptive seen as “pictorial,” since the description of a work of art is always the representation of a representation. This is the realm of ekphrasis, whether the work of art is “real” or fictitious. We shall also see that some descriptions have “pictorial qualities” without being overtly descriptions of works of art. In this case, a list of markers will have to be established so as to be able to affirm that we have an instance of oblique iconotextuality. The multiple framing effects, the focalization, the graphic elements, the pictorial lexicon, the topoi of painting such as Madonnas with child, entombments, genres (still lifes, marines, portraits), the mannerisms, as if conveyed by the text, will constitute a kind of pictorial subconscious of the text which cannot be ignored as it represents an essential dimension of the legible. We shall have to refrain, however, from the temptation of superimposing an image onto a text with which it does not have an organic or structural relationship. The presence and correlation of several markers will be the only way to affirm that this hypotyposis has a pictorial ...