![]() PART I

PART I

Institutions, Social System and Political Economy![]()

Chapter 1

Institutional Interactions in an Evolutionary System Perspective

When used in conjunction with the social, the term systemic, in view of its mechanic and stern overtones in the normative subconscious, stands on the knife’s edge. For this reason, to conduct an institutional analysis from a systemic perspective, a dynamic trade-off should be established between formal and informal institutions with respect to their inter-repulsive and inter-complementary inclinations and among micro-constituencies of a social system, such as individuals, groups and organisations, and macro-constituencies, such as governments, the bureaucracy, and so on. This is because the static and sharp-edged analytic apparatuses of mainstream social systems theory have prompted system analysis to lock in the monolithic, univocal and unidirectional premises of structural functionalism.

Societies are complex systems comprising mutually contingent interrelationships of individuals, organisations and social groups of various types. These relationships generate certain structural principles that bind the overall clustering of institutions across time and space. As the holistic manifestation of this clustering, a social system is the interwoven and interacting stock of formal and informal institutions evolving in a specific timespace. What distinguishes a social system from other systems, such as biologic, ecologic, physical and so on, is that its constituent parts are human-established or artefact institutions based on non-routine and unpredictable behaviours in complex interaction. The latter comprises the mechanic amalgamation of commensurable units such as atoms, cells, microorganisms and so on.

As the basis of social systems, the institutionalisation of social interaction, in an accumulating fashion, paves the way for structuration across time and space. In this sense, institutions, in evolutionary terms, are structure-forming properties of social systems. And a social structure takes on a systemic form because it mediates the patterned or ordered intersections between institutions, thereby obtaining an integrative scope (Giddens, 1984: 16–24). Structures, however, are discontinuous systems, as their principles or institutional underpinnings are subject to constant change. Dynamic structures may contain the changing and evolving character of social systems, but they also fail to capture inter-temporal changes. Thus, including a structure, with its cyclical changes, in an analysis demands a process-based approach. This is because the ‘process is a structure in time’ (Dopfer, 2005: 17).

In terms of the conceptual basis of a systemic analysis of social structures, there are two points that should be clarified. The first is to identify the contradistinctions among structures, regimes and social systems in institutional terms, as these three terms are used interchangeably in an ambiguous manner. According to Andersen (1990: 2), for example, a social policy regime refers to ‘the relations between state and economy, a complex of legal and organisational features are systematically interwoven’. The fundamental prerequisite for a regime is hence an embedded institutional structure that relies on a coherent and inter-complementary, but not necessarily an effective, relationship among its constituents. In this regard, a regime can be defined as a structured ordinariness of institutional interactions.

In political economy terms, the term system, unlike regime, does not require a coherent interconnection, but rather lasting and relational interaction among its constituents. The inter-constituent liaison in social systems, contrary to functionalist structuralism, can generate stable or unstable, but not static or functionally dissipated, structures. Stability and equilibrium are not preconditions for a system to exist or evolve. Rather, social systems arise based on the institutionalisation of norms and values at the formal or informal levels, and the inter-repulsive and inter-complementary tensions between these institutions are mediated by organisational, economic or political actors. (The term inter-repulsive denotes that two or more constituents interact in a way that suppresses or restrains each other’s abilities to enforce certain aims, respectively.) Thus, I will use the term system, in a social sense, to denote structures that have individual or organisational constituents interacting through value-rationally or purposive-rationally in shifting proportions and evolving inter-complementarily or inter-repulsively over time and space.

In brief, structures are static elements of a social system, while regimes signify the patterned alignment of these structures. Social systems are patterned or unpatterned structures in evolution, intersecting with the relational interactions between its formal and informal constituents. Social systems might exhibit regime characteristics, but a lack of these characteristics would not eliminate their systemic nature.

The second conceptual problem is related with a seemingly minor but analytically major distinction. The asymmetric structuration of subdivisions, their relational interaction in a social system and the cross-interactions among various social systems in multiple periods pose a formidable challenge in developing a systemic conceptualisation. This quandary purportedly circumvents a non-functional analysis of social systems. An underlying reason is an analytic misapprehension of the contradistinction of systemic and systematic. Systematisation relies on the functional hypothesis that the (rational) behaviours of A and B have kindred characteristics consisting of linear, measurable and predictable variables; their overall causes and effects and institutional manifestations would be gauged quantitatively by standard benchmarks, and the normative implications of these tenets are not an independent variable in the conduct of social action (Buckley, 1967: 76).

For example, the game-theoretical explanation of institutional interactions is rooted in the fact that institutions jointly regularise social behaviour, and this regularised conduct of behaviours enables each actor to assume that ‘his opponents are rational, that they mode the game exactly as he does, and that they assign the same correct priors’ (Greif, 2006: 129). In other words, in a game-theoretical analysis, it is pre-accepted that players have a common knowledge of rationality, the mainstay for an equilibrium game to be played by rational actors (Greif, 2006: 124). The institutional environment consists of a restricted web of regularised rules that provide the actors with common (standard) knowledge for making the rational choices. As a result, ‘games need to be kept very simple: few actors, few options’ (Pierson, 2004: 61). This denotes that in analytic terms, the cognitive complexity of identifying Nash equilibria falls short of making a holistic analysis in case the number of independent players and the variety of their strategic options increase beyond a very few. Furthermore, the sequence or evolution of inter-actor games cannot be interrupted because ‘sequence, in these models, refers to an ordered alternation of “moves” by “composite actors” with preferences and payoffs fixed in advance’ (Scharpf, 1997: 105).

For these reasons, the game-theoretical methodology is far from enabling us to develop such a systemic perspective. (It is true that as noted above, institutions are the products of societal norms and values. But this fact cannot be used as the main basis for a determinist, functionalist explanation of inter-actor relationships under an ex ante restricted and standardised setting.) Because a systemic analysis of institutional interactions should include: (i) the potential and irregular extension or contraction of the boundaries of an institutional environment; (ii) all major actors that exert impact on the conduct of a system, their changing pro-cyclical and countercyclical positions under changing composition of coalitional constellations, and the irregularity of their reactions to each other at each institutional system cycle; (iii) changing composition, density and trajectory of power relationship between the actors; and (iv) the ex ante undeterminable and unsystematic sequence of path-dependent change dynamics in timespace. (Each of these analytic points will be elaborated in due course.)

Of particular importance for a systemic analysis of social action, in addition to the above listed ones, is the incorporation of informal institutions (norms and values) into analysis as an independent variable rather than a means to regularise or communise the purposive-rational action. For example, Weber (1947: 168) proposes the commonly employed measures of rational economic action as follows: the systematic acquisition, production and distribution of utilities. If one presupposes that the core of systemic analysis relies on the systematic delineation of the normative implications of social interactions, then developing a non-functional system analysis of an institutional whole becomes inconceivable. Systemic analysis, nonetheless, does not or must not rely on the systematised or imbricated (regularly overlapped) resources of social knowledge. Its essence is to include the combined impact of the normative or rational implications of inter-institutional interaction in the analysis.

Systematicness cannot be systemic in this sense, as it omits both the purely normative and normatively contingent or value-rational implications of social conduct. When adopting a systemic perspective, a social analyst should presuppose that there are cryptic constellations, ineffable niches of social phenomena, in these interactions that would not be standardised by numeric measures. Instead of generating abstract knowledge at the expense of theoretical concretism, she/he aims to conceptualise institutional interactions in terms of their intersectional implications at the level of the social system and its subdivisions. This would, in effect, help the researcher to understand and identify the framework of the overall stock of institutions and manage the co-evolution of formal and informal institutions to determine the best available combination of mutual-enforcement. (The latter does not refer to top-down design but rather the orchestration of the institutional structure.)

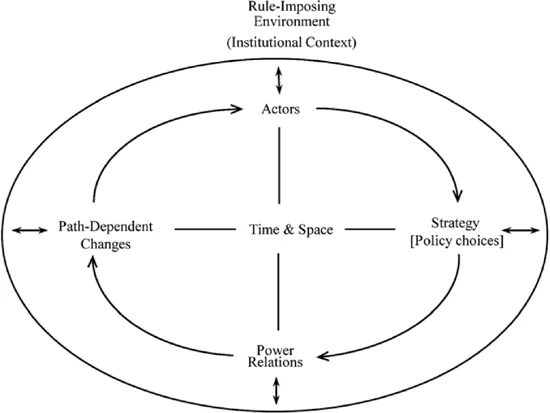

Ultimately, a systemic analysis of institutions should neither be overvalued nor undervalued because it is implausible to expound entire institutional interactions (through a panacean systemic analysis), especially given their informal implications. It would nonetheless be tenable: (i) to perform a reciprocally dependent and inter-repulsively or inter-complementarily contingent inquiry into institutional interactions within a social whole; and (ii) to ascertain the interlaced and process-based evolution of these interactions over time and space. In this book, the institutional system analysis is proposed to be a framework for performing these two interconnected objectives in an evolutionary perspective. As can be seen in Figure 1.1, the main constituents of this analysis are composed of institutions, actors and their strategies, power relations between the actors and path-dependent changes arising out of these relations. What makes this institutional analysis systemic is that it first offers a holistic perspective that interconnects these four constituents and then explains their interactional dynamics in a co-evolutionary perspective.

Figure 1.1 Evolutionary rhythm of the institutional system

Therefore, while proposing such an analysis, on the one hand, in addition to constructing its general framework, I will also try to explore a combined way of thinking over institutional environment, actors, power relations, and offer new patterns of path-dependent changes. Besides, I will naturally utilise the available concepts, definitions or investigations proposed in the relevant area of research. While citing these concepts or definitions or exploring the others, my ultimate purpose is to bring the four constituents of institutional system analysis together in tandem with its general explanatory framework.

Institutions as Interaction Channels

In a systemic analysis, institutions are the core constituents of the integrated structures of societies because they are the interaction channels that give life to the embodiment of a social system. Ascertaining and clarifying the definition of an institution is therefore a significant primordial step for institutional theory, as the former specifies the trajectory along which the latter’s analytic path develops. In a systemic perspective, institutions can be defined as the building-blocks of social order; they represent mutually related rights and obligations enforced by specific categories of actors to regulate, liberate or expand individual and collective action (Streeck and Thelen, 2005: 9; Commons, 1959). An underlying feature of this definition is that, as interaction channels, institutions structure mutual relationships among individuals and organised actors. In this sense, they are constitutive of social and economic intercourse (Bromley, 2009: 45).

Institutions are constraining and enabling, namely liberating and expanding the right to act in certain forms. Here, constraint is used in the sense of structural constraints. It refers to the structuration of social systems as spaces of asymmetric power, denoting that constraints allow or disallow some actors from instrumentalising the structure’s resources to enforce their goal and aims (Giddens, 1984: 170–176). In Streeck’s words (1997: 197), (beneficial) constraints exist because ‘a society requires a capacity to refrain advantage-maximising rational individuals from doing things that they would prefer to do, or to force them to do things that they would prefer not to do’. The object of constraint-contingent structuration is to sustain the trilogy of the social optimum (economic efficiency, social equity and individual liberty) by proactively regulating destructive interactions of unfettered utility-maximisers.

This is a structural crossroads where institutional interaction encounters the trilogy of conflict, dependence and order (Commons, 1959: 118). In the economic realm, for example, every economic transaction is bound to set off a conflict of interests because each actor or economic unit intends to obtain as much, and give as little as possible. On the one hand, such a mutually destabilising interaction creates dissensus among its participants. On the other, for social systems to maintain their existence there should be a trade-off point, an order, upon which workable mutualities can be predicated on the basis of mutual dependencies. As orders, especially the capitalist order, are barely sustained by voluntary action, there should thus be collectively binding arrangements to compel each party in the interaction to comply with the prerequisites of the social order by exhibiting performance, avoidance or forbearance.

A social analyst who disregards the inter-complementary quality of the conflict, dependence and order is likely to make a bounded definition of institutions. For example, to North (1990: 3), institutions are ‘the rules of the game in a society or, more formally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction’. And the economic institutions ‘define property rights, that is the bundle of rights over the use and the income to be derived from property and the ability to alienate an asset or resource. The function of rules is to facilitate exchange … Political institutions … reduce uncertainty by creating a stable structure of exchange …’ (North, 1990: 47–50). The boundedness of North’s definition stems from his failure to even tangentially address the issue of power and its role in the process of economic change and performance, as he concentrates on smooth economic processes rather than their rough political manifestations at the level of social economics and social politics.

In political economy terms, does it matter that a rule in a country’s constitution stipulates that the state should take the action necessary to ensure and sustain equality of opportunity if there is not a level playing field for the underprivileged to obtain this opportunity? Within this context, Streeck and Thelen (2005: 11) draw attention to the authority, obligation and enforcement-creating nature of institutions. For a rule to impose a workable constraint upon an action, it should hence have systemic, complementary linkages to other constraining tools within a structure to enforce its aim. This is the precondition for an institution to be an effective institution, the de jure presence of which then becomes a de facto constraint on actors. In this case, the actors will become aware that it is highly likely that they will be sanctioned for a potential noncompliance. The reverse is true for ineffective institutions.

Formal and Informal Institutions in Interactional Perspective

Institutions, formal or informal, are not mutually exclusive but inter-complementary or inter-repulsive (Dopfer, 2005: 26). Formal institutions such as state-enforced rules (legal frameworks, constitutions and so on) or organisational procedures regulate social action. This need not come in the form of a purely rational initiative, but may also be a normatively contingent rational initiative. As an integral part of culture, informal institutions such as norms, values, habits, standard practices, customs, traditions and conventions are the products of communicative action among individuals (Mantzavinos, 2001: 101–52). They are, in this regard, socially shared rules, namely forged, communicated and enforced through social interaction.

Informal institutions are, in a broad sense, composed of values and norms. Values are conceptions of the preferred or desirable combined with the construction of standards through which existing structures or behaviours can be compared and assessed. A value system is, in other words, a rule that an individual uses to select which of the mutually exclusive actions he/she will undertake (Arrow, 1967: 3–4). Norms, including ethical and moral codes, specify how things should be done. They define legitimate means to valued ends (Scott and Meyer, 1994: 58). As they appear in socially shared expectations, norms are benchmarks for a given pattern of behaviour (Elster, 1989: 97).

Values are shared beliefs regarding what is good/bad or true/wrong, and therefore underlie the structure of a society and the variety of its culture. Internalised values also determine the action orientations of individuals, groups and so on. In conjunction with values, norms are created to monitor and enforce cultural values, shared rules of conduct, that orient individuals regarding how they should act in specific situations (Horne, 2001: 4). The normative defines the domain of these shared rule-conditioned or value-rational actions (Elster, 1989: 150–151).

When it comes to a systemic perspective, the interactional explanation of formal and informal institutions becomes paramount as it is an analytical priority to shed light on the structuration, restructuration or destructuration of social institutions in terms of their inter-complementary and inter-repulsive inclinations. Habermas’ conceptualisation of communicative action can be suggested to be the best available means for making such an interactional explanation of institutions.

The communicative action literature stems from Mead’s symbolic interactionism, Wittengstein’s concept of language games, Austin’s theory of speech acts and Gadamer’s hermeneutics. As the contemporary proponent of this tradition, Habermas (1984, 1987) contextualises communicative action within three societal constituencies – personality, culture and society – into the lifeworld and social system, two areas of interaction that unfold in an inter-repulsive process. Personality denotes the competences that make a subject capable of speaking and acting. Culture is the stock of knowledge that supplies its participants, persons, with interpretations during communication as they attach meanings to something in the lifeworld. Finally, societies are the systemicall...