- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

French Connections in the English Renaissance

About this book

The study of literature still tends to be nation-based, even when direct evidence contradicts longstanding notions of an autonomous literary canon. In a time when current events make inevitable the acceptance of a global perspective, the essays in this volume suggest a corrective to such scholarly limitations: the contributors offer alternatives to received notions of 'influence' and the more or less linear transmission of translatio studii, demonstrating that they no longer provide adequate explanations for the interactions among the various literary canons of the Renaissance. Offering texts on a variety of aspects of the Anglo-French Renaissance instead of concentrating on one set of borrowings or phenomena, this collection points to new configurations of the relationships among national literatures. Contributors address specific borrowings, rewritings, and appropriations of French writing by English authors, in fields ranging from lyric poetry to epic poetry to drama to political treatise. The bibliography presents a comprehensive list of publications on French connections in the English Renaissance from 1902 to the present day.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access French Connections in the English Renaissance by Catherine Gimelli Martin,Hassan Melehy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Translating and Transferring Gender

Chapter 1

“La Femme Replique”: English Paratexts, Genre Cues, and Versification in a Translated French Gender Debate

A.E.B. Coldiron

Some of the first and strongest connections between France and England in the early modern period are to be found in the many poems translated personally by, or under the general auspices of, the earliest printers in England. Before the mid-century organization of the Company of Stationers, many early printers in England were francophone appropriators of the materials, texts, and textual aesthetics of French print culture. William Caxton, Wynkyn de Worde, Richard Pynson, Robert Wyer, and others generated the first century of English printed poetry in significant measure from French raw materials and literary habits. Before 1557, many more English printed poems were translated from French than were translated from Italian—about six times more, according to William Ringler’s count—and this fact has a number of far-reaching implications for the periodization and canons of English Renaissance poetry (and for the practice and theory of literary history more generally).1 But this essay only looks across the English Channel at one especially curious instance of that wider appropriative process, an early gender-debate poem translated from French. Examined as a pair, the Interlocucyon, with an argument, betwyxt man and woman and the Débat de l’homme et de la femme exemplify the filtered, altered, individuated character of many of the early printer-translators’ appropriations from France. Here I argue that the verbal and visual strategies of translation in the Interlocucyon reveal the early English printers’ varied, experimental appropriations of certain elements of French gender discourses and their refusal of others. The French and English versions participate in their respective literary cultures, but these elements position each differently within its own culture. In other words, the same content comes to mean something rather different because the apparently slight interventions of the printer and translator have much larger stylistic and literary-aesthetic consequences.

One of Wynkyn de Worde’s many imprints about women and gender relations, the Interlocucyon betwyxt man and woman … is a translation of Le Débat de l’homme et de la femme written by Guillaume Alexis in about 1460 and printed at least seven different times before 1530.2 Unlike most of Wynkyn’s other output, however, this little book is notable for giving the woman the last, longest word. Well before Gosynhill’s Schole House for Women and Mulierum Paean break out the traditional arguments into separate he-said-she-said treatises, this work voices a male and female speaker in direct debate, flinging stanzas at each other inside one poetic work. The work’s early appropriation of French gender discourses, and particularly its amplified female interlocutor, anticipates the better-known English debates of the mid and late sixteenth century.3

Michel-André Bossy and Diane Bornstein have provided excellent, foundational readings of this work, well worth brief review here. Bornstein summarizes the positions of the two speakers:

In the debate both the man and the woman base their arguments mainly on scriptural authority. The man begins with Eve to demonstrate the evil of women. In turn the woman counters with the Virgin Mary, an example she uses several times.… The man uses all the traditional anti-feminist jibes: women paint their faces and waste money on clothes; they deceive men, flatter, and lie; they speak too much, scold, gossip, contradict men, and reveal their secrets; they are avaricious … The woman … [enumerates] the virtues of women: they are chaste, religious, and merciful; they are good nurses and mothers; and they are generous patrons when they own property. (viii)

Bornstein points out that “for most of the debate the woman is on the defensive” until the long final section in which “she cites a series of negative male examples … men are aggressive, violent, deceitful, and ungrateful; they often act as murderers, tyrants, criminals, and war mongers; instead of slandering women, who are their mothers and nurses, they should be grateful to them” (ix). Bossy, writing about the French version, explains that while Alexis’s oeuvre is generally anti-feminist, this work defends women even though it appears to debate the question.4 The long final section’s unanswered condemnations of men and the French version’s verbally adept female speaker create this unusual result.

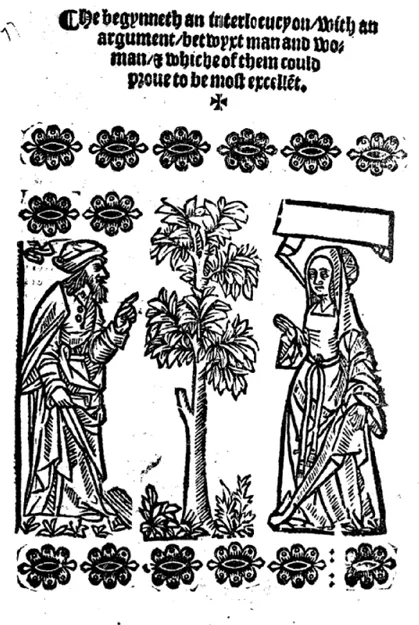

In their content, the French and English versions differ very little. But the English translation, even while preserving content, makes meaningful changes to the French text. Paratextual changes, for instance, may not alter a work’s content, but they matter a great deal in how French gender debates are conveyed to English readers. In the case of the Interlocucyon, the printer and translator create a complex and specifically literary set of frames for the English version of the debate. First, the translation passes itself off as an English work: in the framing paratexts, at least, there is no mention of a source or of the French version. (In Lawrence Venuti’s terms, it is an “invisible” translation, pretending to be a native; this debate is to be claimed as English.) While most extant French imprints include in the title or colophon Guillaume Alexis’s name and status as a monk (the “Prieur de Bucy”), Wynkyn’s edition bears no author’s name. Many of Wynkyn’s other translated works are invisible in the same way, so this suppression of Frenchness and of authorship are not unusual in Wynkyn’s output.5 Wynkyn’s habit, like that of many early English printer-translators, was to adopt not only texts but layouts, page design, woodcuts, book design, typefaces, and so on; this imprint is no exception. The English Interlocucyon does include two woodcuts, and Wynkyn may have taken the design concept of this work from one of the many extant French imprints.6 The title cut Wynkyn uses (Figure 1) resembles a stock woodcut found in French marriage complaint poems, and its male figure also appears in the title cut of another early translated French debate poem (The Seyenges of Salomon and Marcolphus, 1529). Bornstein thinks that the title cut to the Interlocucyon signals the printer’s understanding of the work as anti-feminist (vii). I think it also indicates his understanding that both imprints are part of a general area of interest for his readers—“woman questions”—a topic that can be usefully advertised to customers with such commonly reused woodcuts, part of a strand or sub-genre of discourse that will be identifiable and marketable. The title woodcut depicts the poem exactly: a debate between a man and a woman; but it may do more than that, whether as part of a plan or because of a technological problem in the woodcut.

Several colleagues have suggested to me that the blank speech banner above the woman’s head is a sign that she is silenced, but I would argue the contrary: blank banderoles were common above early interchangeable cuts. Furthermore, the woman has both a speech banner and a speaking hand gesture, while the man, who does have a speaking hand gesture, has clearly had his speech banner obliterated by two pieces of border design that are asymmetrical, obvious additions. Other uses of this same factotum man, such as the Salomon and Marcolphus title cut, do allow him his speech banner. (Perhaps it was thought easier to debate a king than a woman; or perhaps the speaking figures supplicate, while the silent figures are the more powerful.) Was it really a selling point for Wynkyn’s book that the woman silences the man on the title page? Was it even deliberate on Wynkyn’s part—or might the inserted, asymmetrical border design have merely been used to try to cover a problem with the woodblock or in the printing process? (The male figure’s reappearance in 1529 appears to be a re-cut, but I have not examined the original to be certain.) What is certain is that the title cut to the Interlocucyon is not only a more direct representation of text than Wynkyn usually gives, but also a more specific one, since regardless of the printer’s motives, the image illustrates, with the obliterated speech banner above the male factotum figure, that the woman will be the dominant speaker in this debate (which she in fact turns out to be, in her long last-word finale section). That important final element of the French debate poem, the woman’s long unanswered catalogue of bad men, is not only translated verbally but is represented visually in the title image.

Fig. 1 Title page from Interlocucyon, with an argument, betwyxt man and woman, & which of them could proue to be most excellẽt. Anon. (London: de Worde, 1525). © British Library Board, Shelfmark W.P.9530. All rights reserved.

The next woodcut in the work, on the title verso, is a famous, oft-used cut of the cleric-at-desk. However odd it seems to modern readers at first glance, this cut may be a visual gesture to the authorship, genre, and literary history of the French source. The French versions generally mention Guillaume Alexis as author in colophons or titles, if not by name, then as the Prieur de Bucy. While there is no mention in the English version of Alexis or of any French author, this verso image at least puts a monk-figure at the threshold, thus placing the work in a clerical or scholarly tradition of “woman question” treatises, perhaps in the line of Mathéolus or Jerome. This dual-woodcut presentation makes a certain kind of sense, signaling readers first that the work is a gender debate in which the woman dominates strongly, and next that the work may have clerical origins and may be expected to trot out the standard misogynist topoi for popular consumption.

However, while the poem itself fulfills entirely the promise of the debate-scene title cut that the woman’s part will overpower the man’s, and while the male speaker’s part of the poem fulfills the verso cut’s promise of clerical misogyny, the poem’s verbal frame—a frame added by the English translator—adds a third, rather more complex implication. The new English framing speaker overhears the man and woman debating as if in a chanson d’aventure or (day)dream-vision poem. The new verbal frame thus positions the work differently still: this will indeed be a debate, with male misogyny silenced by female speech, but it will also locate itself against courtly as well as scholarly traditions. The English-added frame begins

When Pheb[us] reluysa[n]t / most arde[n]t was a shene

In the hote sommer season / for my solace

Under the umbre of a tre / bothe fayre [&] grene

I lay downe to rest me / where in this case.

As after ye shall here / a stryfe there began

Whiche longe sys endure / with great argument

Bytwyxte the woman / and also the man

Whiche of them coulde proue / to be moost excellent.

The man.

The fyrst whiche I herde: was the ma[n] that sayde

…

At this point the actual debate begins. After 49 quatrains (the last 11 of which are spoken by the woman), the translator adds the following framing lines to end the poem:

The auctor.

Of this argument / the hole entent

I marked it / effectually

And after I had herde / them at this discent

I presed towardes them / incontynently

But when they sawe me / aproche them to

Lest I wolde repreue / theyr argument

Full fast they fledde / then bothe me fro

That I ne wyst / whyther they went

Wherfore now to iudge / whiche is moost excellent

I admyt it / unto this reders prudence

Whyther to man or woman / is more conuenyent

The laude to be gyuen / and wordly [sic] magnyfycence.

The chanson d’aventure frame is also, of course, French-born. Related to the medieval dream vision (even though this speaker never actually admits to falling asleep), this frame places explicit responsibility on the readers to draw their own conclusions (“I admyt it unto this reders prudence”). Both dream-vision and chanson d’aventure frames allow the narrating or authorial speaker a safe distance from the topic and an appearance of neutrality. So the translator frames Alexis’s bare debate with a revised authorial persona—not the author named in th...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Permission Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part 1 Translating and Transferring Gender

- Part 2 Textualizations of Politics and Empire

- Part 3 Translation and the Transnational Context

- Appendix: Ronsard in England, 1635–1699

- Bibliography: Scholarship on the Anglo-French Renaissance

- Index