eBook - ePub

Costuming the Shakespearean Stage

Visual Codes of Representation in Early Modern Theatre and Culture

- 210 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Costuming the Shakespearean Stage

Visual Codes of Representation in Early Modern Theatre and Culture

About this book

Although scholars have long considered the material conditions surrounding the production of early modern drama, until now, no book-length examination has sought to explain what was worn on the period's stages and, more importantly, how articles of apparel were understood when seen by contemporary audiences. Robert Lublin's new study considers royal proclamations, religious writings, paintings, woodcuts, plays, historical accounts, sermons, and legal documents to investigate what Shakespearean actors actually wore in production and what cultural information those costumes conveyed. Four of the chapters of Costuming the Shakespearean Stage address 'categories of seeing': visually based semiotic systems according to which costumes constructed and conveyed information on the early modern stage. The four categories include gender, social station, nationality, and religion. The fifth chapter examines one play, Thomas Middleton's A Game at Chess, to show how costumes signified across the categories of seeing to establish a play's distinctive semiotics and visual aesthetic.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Costuming the Shakespearean Stage by Robert I. Lublin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Ancient & Classical Drama. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Sex and Gender

dost thou think, though I am caparison’d like a man, I have a doublet and hose in my disposition?

As You Like It (3.2.194–6)

Before an actor on the Shakespearean stage delivered his first words in performance, the audience would have seen how he was dressed and understood whether the character he was playing was male or female. This seems obvious, but it is also significant and has far reaching consequences for how meaning was constructed in performance and received by audiences in early modern England. Since all of the actors in the public playhouses were male, the costume one wore served to establish, not merely reflect, one’s sex in performance.1 I say “sex” instead of “gender” (although it is anachronistic to draw a distinction between the two at this point in history) to highlight the fact that there was no biological basis to appeal to when all of the characters were played by male actors. Quite simply, as Stephen Orgel has stated, “clothes make the woman, clothes make the man: the costume is of the essence.”2 Since the biological sex of all of the actors was male, the essence or root basis of a character’s sex lay overwhelmingly in the manner in which costumes were employed onstage.

To explore this phenomenon, this chapter will begin by presenting the basic apparel that was common to early modern England and most frequently seen on its stages. What becomes immediately apparent from such a survey is that clothing from the period can only be presented logically by first dividing the articles according to whether they belonged appropriately at the time to men or women. The clothes themselves held gendered associations, ones they carried onto the actors who wore them in performance. The second part of the chapter will explore these associations and consider the consequences they had for the playwrights who considered them when they wrote the plays, the actors who donned them when they took part in productions, and the audiences that interpreted them when they observed performances. What becomes apparent from such a study is that sartorial choices served to construct notions of sex and gender every bit as vigorously for the stage as did the spoken lines of any play.

Clothing Essentials

Whether or not Shakespeare’s plays are for all time, they were originally written, as were those of his contemporaries, for a very particular time and place, specifically the professional stages of early modern London. The spatial and temporal specificity of the period’s drama becomes particularly conspicuous when we look at the frequent references made to apparel, which nearly always mention contemporary items commonly worn in England. For modern readers to engage with the manner in which plays signified to their original audiences, it is crucial that we familiarize ourselves with the articles of clothing that were worn at the time.

Throughout the period from 1567 to 1642, there were a number of basic components of clothing for men and women that altered in style but remained staple items. The fundamental garments of the Elizabethan and Jacobean period were the same ones that had maintained for over a hundred years and would remain so until the latter half of the seventeenth century.3 The list of garments that follows makes no attempt at comprehensiveness. There are innumerable additional articles of clothing and fashion trends that could be listed and described.4 Here, I merely wish to establish a starting point from which we can consider the visually based semiotics according to which early modern audiences understood the apparel worn on English stages.

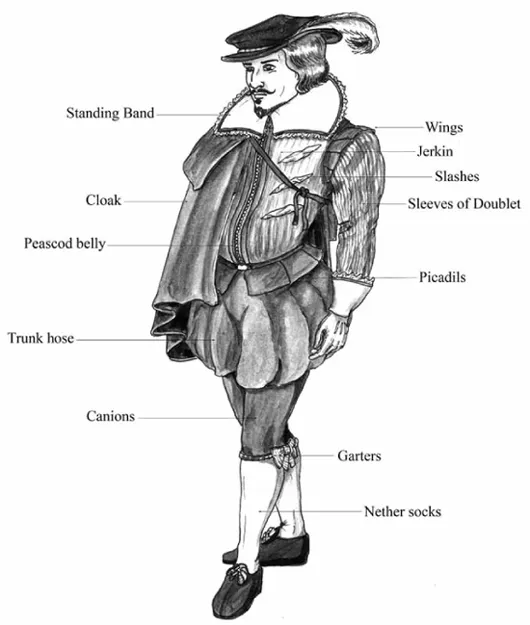

For men, the most commonly worn articles of apparel include the shirt, doublet, breeches, nether hose, jerkin, cape, robe or gown, ruff or band, hat, and footwear; for women, the chemise, dress or kirtle, farthingale, gown, ruff or band, headdress, and footwear. To clarify how this clothing actually appeared, Figure 1.1 presents a generalized Elizabethan gentleman. I urge readers to view this picture cautiously, for it suggests that the fine clothes depicted represent the norm at the time and threatens to occlude the enormous differences that marked people of different classes, a topic which will be pursued in Chapter 2. The picture is useful only for helping to familiarize readers with the particular articles of apparel. In much the same way that a wealthy man and a poor man in the twenty first century might both wear shirts, pants, shoes, and sport jackets yet look radically different, so was it possible for gentlemen and laborers in early modern England to wear the same basic articles of apparel yet present very different images.

Fig. 1.1 A Generalized Elizabethan Gentleman, drawn by Adam West.

The man’s shirt was typically made of white linen and served primarily as an undergarment until roughly 1625, after which time the fashion changed and it was more commonly seen through the doublet. It was usually cut full and gathered into a round or square neckline, having long, raglan sleeves. Even before 1625, the fabric of the shirt might be seen through the doublet if there were slashings or panes, cuts made in the outer garment that allowed the undergarment to be seen. Among the wealthy, it was common to wear shirts that were embellished with drawn-work and embroidery.

The doublet was a thick, quilted upper garment of velvet, silk, satin, leather, or other material, which extended from the neck to below the waist and was buttoned up the center. Until 1580, the doublet was snug against the body, at which time the practice of having a peascod belly, a swelling lower abdomen, became popular. This fashion lasted until roughly 1610 when form-fitting doublets once again became the norm.5 The sleeves of the doublet were sometimes detachable and would be connected by points, laces or ties which ended in small metal tips. Points were used to connect separate pieces of clothing at the time and required that a person receive assistance from others while dressing him or herself.

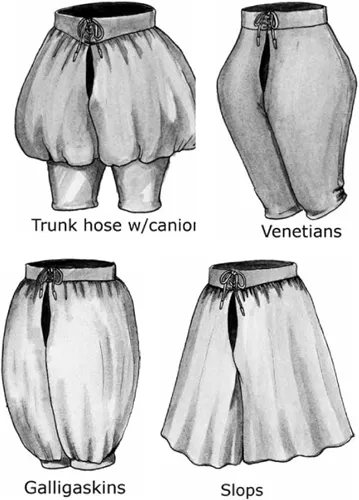

Breeches go by many names in the early modern period including: trunk hose, canions, Venetians, galligaskins, and slops. They constituted the upper part of the hose or stocks and served to cover the top part of the leg. The various terms for this article of clothing are used interchangeably in the drama of the period but distinguishable features for each can be identified. Trunk hose generally were well rounded and reached from the waist, where they were connected to the doublet by points, to the middle of the thigh, where they were connected to the nether stocks, which were much like stockings. Canions were close fitting extensions that were sometimes used to connect the trunk hose to the nether stocks; they typically reached from mid-thigh to the knee. Panes were often worn over the trunk hose and consisted of strips of fabric that reached from the waist to the bottom of the breeches. Venetians were breeches much like trunk hose but reached down below the knee. Galligaskins sloped gradually from a narrow waist to fullness at mid-thigh. Slops was a particularly slippery term that could refer to almost any breeches, but it could also refer to wide ones that were open at the knees. Breeches could follow the shape of the leg or be heavily padded with bombast, a stuffing made of almost any available fabric. The various terms defined here give some idea of the various fashions at the time, but we should be careful about assuming that we know how an actor’s breeches looked simply because the lines of a play say that he is wearing a particular style since the terms were sometimes used interchangeably, even indiscriminately.

The nether stocks were worn like tights and showed off the leg of the wearer. They were held up with garters, lengths of cloth or silk that were tied around the leg, either above or below the knee. The brief fashion for cross-gartering, already outdated when Malvolio adopts it in Twelfth Night, consisted of wearing either garters both above the knee and below the knee or a single band rolled back on itself so that it would serve as a garter above the knee and below the knee and be crossed behind the leg.

The jerkin was a jacket-like garment that was worn over the doublet. In many of the paintings from the era, the jerkin is made of the same material and follows the same pattern as the doublet. As a result, it is sometimes difficult to tell if a jerkin is being worn. Jerkins frequently had short puffed sleeves or no sleeves. Most paintings of the era show the jerkin drawn in to the waist, but sometimes it had a peplum or basque, i.e., a skirted extension that covered part or all of the breeches.

Fig. 1.2 Breeches, drawn by Adam West.

English capes or cloaks were regularly half-length, extending from the shoulder to the middle of the body and are shown in most paintings to be slung over the left shoulder only. They often had fake sleeves attached. Capes or cloaks were apparently considered indispensable traveling gear for the gentility, for mention is made of men who are compared to tapsters for appearing without their cloaks.6 Later in the sixteenth and into the seventeenth century, longer cloaks came into fashion in England.

Robes or gowns in early modern England reached to the ground and typically had large funnel-shaped or hanging sleeves. Before the middle of the sixteenth century, short gowns that reached to the hips were common and many depictions of Henry VIII show him wearing one. Pictorial evidence suggests that after 1550, the practice of wearing short gowns was replaced by the fashion of wearing a cloak. Full length gowns were the common attire of the professions: academicians, lawyers, judges, physicians, clergy. They were also commonly worn by older men and by members of the middle class on ceremonious occasions.7

The ruff was a popular fashion for most of the Elizabethan and Jacobean period. It appears merely as a small cambric, holland, lawn, or lace frill at the neck in illustrations prior to 1570. After that time, particularly as a consequence of the introduction of starch into England in 1564, the ruff expanded greatly. The starch held the ruff in a particular shape and kept it from bending.8 In Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist (1610), Subtle describes a man wearing a large ruff: “He looks in that deep ruff like a head in a platter” (4.1.24).9 James Laver notes that the ruff, growing sometimes to a quarter of a yard in radius, was an article of clothing worn exclusively by gentlemen since it emphasized the fact that its wearer did not need to work.10 The enormous ruffs that became more common towards the end of Elizabeth’s reign may lead one to wonder how the wearer managed to eat. And yet, this article of clothing is so common in the portraits of nobles and gentry in the era that we must understand it to be common apparel of widely accepted taste. Instead of wearing a ruff (or even in addition to it), Englishmen sometimes wore collars, called bands. One could wear a falling band which folded down from the neck or a standing band that would stand out from the neck with the aid of starch. Matching ruffs or bands are often seen on sleeves in paintings from the period. By the 1630s, the band had largely replaced the ruff in English clothing.

Two types of hats were most popular in the Elizabethan and Jacobean period. The first, a bonnet, is low-crowned, made of soft material, and often decorated with a feather. The second is high-crowned, made of a stiff material, and built in sugar-loaf form.11 Flat caps were also widely worn, primarily by citizens and apprentices. They were round, had a narrow brim, and were flat across the top. In 2 The Honest Whore, Dekker explains how flat caps were understood at the time by stating that “Flat ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Sex and Gender

- 2 Social Station

- 3 Foreigners

- 4 Religion

- 5 “An vnder black dubblett signifying a Spanish hart”: Costumes and Politics in Middleton’s A Game at Chess

- Works Cited

- Index