eBook - ePub

Challenging History in the Museum

International Perspectives

- 262 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Challenging History in the Museum

International Perspectives

About this book

Challenging History in the Museum explores work with difficult, contested and sensitive heritages in a range of museum contexts. It is based on the Challenging History project, which brings together a wide range of heritage professionals, practitioners and academics to explore heritage and museum learning programmes in relation to difficult and controversial subjects. The book is divided into four sections. Part I, 'The Emotional Museum' examines the balance between empathic and emotional engagement and an objective, rational understanding of 'history'. Part II, 'Challenging Collaborations' explores the opportunities and pitfalls associated with collective, inclusive representations of our heritage. Part III, 'Ethics, Ownership, Identity' questions who is best-qualified to identify, represent and 'own' these histories. It challenges the concept of ownership and personal identification as a prerequisite to understanding, and investigates the ideas and controversies surrounding this premise. Part IV, 'Teaching Challenging History' helps us to explore the ethics and complexities of how challenging histories are taught. The book draws on work countries around the world including Brazil, Cambodia, Canada, England, Germany, Japan, Northern Ireland, Norway, Scotland, South Africa, Spain and USA and crosses a number of disciplines: Museum and Heritage Studies, Cultural Policy Studies, Performance Studies, Media Studies and Critical Theory Studies. It will also be of interest to scholars of Cultural History and Art History.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Challenging History in the Museum by Jenny Kidd,Sam Cairns,Alex Drago,Amy Ryall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Museum Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Museum StudiesPART 1

The Emotional Museum

Historically, museums developed as Enlightenment (or post-Enlightenment) institutions grounded in reason and intellect and, within this framework, came to house the greatest and most significant cultural artefacts in line with those values. The museum’s role quickly developed into one of preservation, of collections and ideas, and communication, of a narrative – an interpretation – of our past achievements and failures (Bennett 1995). Historical, economical, political and cultural factors have shaped these complex and diverse narratives, and it is this combination of variables that has made museums and their collections such nuanced and absorbing subjects to deconstruct.

If museums were ever radical it was in the period of their birth as institutions that distanced themselves from accepted interpretations of history based on both tradition and dominant religious viewpoints. Over time, and as there was a general societal shift toward secularism, museums lost this radical edge, as their emphasis shifted toward exploring and maintaining their cultural value and communicating this to their visitors.

In this mode museums have a tendency to look backwards, towards the past. Their collections are steeped in ideology and entrenched in meta-narratives that are so embedded that most museums have become conservative, traditional and slow to embrace change. That said, this approach has generally worked in the favour of museums. Not only does it reinforce the value of the collection, both culturally and economically, which in turn justifies the museum’s privileged existence, but it also reinforces the expertise of the curator and endows them with their own ‘aura’ to complement that of the museum object (Benjamin 1936).

One significant development in museological history has been in the strategic repositioning of museums as learning institutions (Hooper-Greenhill 2007). In an era in which formal learning was largely characterised by the one-way delivery of information from teacher to student it is no surprise that the prevailing museum-as-learning-institution model that developed (and has endured) has been similarly so: the museum-as-expert imparts specialist technical information to the visitor who passively receives.

With this in mind, then, the traditional museum exhibition tended to be about specific subjects. A visit may be interesting, even inspiring, sometimes exhausting, but with any luck visitors will leave a museum having learned more about a subject. It has been a rare thing indeed to visit a museum to learn how to do or become. A museum may be a learning institution, but it is certainly no school, college or university.

Part 1 of this volume seeks to explore what happens when museums are asked to do more. To make visitors feel, inhabit and engage in ways that are emotional and often embodied. It picks up on those questions identified in Kidd’s Introduction about how, why and on what basis empathetic engagement with heritage is seen as desirable.

Given their long history of prizing reason, intellect and objectivity, the idea of provoking emotional engagement may be something of an uncomfortable one for many museums, introducing a lexicon that makes us squeamish. Emotion, empathy, experience: are these outcomes not too difficult to articulate, to ‘measure’? Perhaps, and we should acknowledge these challenges, but it is also important to recognise that museums can offer much more to their audiences than the traditional passive learning experience described above. Museum learning should be a more active process, an engagement with experience that results in a changed perception or behaviour for the learner. Accepting this definition casts new light on the museum’s current and potential future role as a learning institution and empowers museums to engage responsibly with the lexicon noted above.

It is not our intention to suggest that we dispense with traditional core institutional values wholesale and replace them with intellectual subjectivity and emotional exploitation. Rather, the chapters in this section on the emotional museum respond to a recognised need within the sector to offer alternative means of engagement. Indeed, they recognise that, to varying degrees, emotional ‘work’ is what museums have been doing all along, not least in programmes that seek to deal with challenging histories. Such engagements offer one means by which challenging museum objects or narratives might be better interpreted, taking visitors from a ‘So what?’ response to a position where they can better connect with their significance.

The contributions that follow are not dismissive of the values that have made museums such important institutions. Instead, being deeply respectful of them, they fully acknowledge the curatorial expertise that gives them their authority, as well as the need to find ways of engaging with emotions appropriately and ethically.

On an institutional level, David Fleming’s work on the concept of the emotional museum has revolutionised National Museums Liverpool. While it has its critics, this approach has been hugely successful, and Chapter 1 highlights the potential for transformative institutional impact when a museum better understands its audience, their needs and expectations as related to their locality and its specificities and infuses the galleries with this knowledge.

Onciul’s case-study of the representation of indigenous history in Canadian museums in Chapter 2 and Rosendahl and Ruhaven’s comments on the challenges associated with delivering an appropriate visitor experience at Stiftelsen Arkivet, a former Gestapo regional headquarters in Norway, in Chapter 5 raise interesting questions and sensitivities about the interpretation process in dealing with difficult and challenging histories, the importance of relationships with their communities in delivering this, and the role that museums can play in community cohesion, whether local or global.

Storytelling is a universal human language, and its role in exploring difficult and sensitive histories is assessed in the work of both Bryan (Chapter 4) and Powers-Jones (Chapter 3). Bryan’s work on theatrical performances inside the museum highlights the medium’s power to re-animate collections and spaces and therefore history itself, asking questions about authenticity and its consequences. Through the writings of Hugh Miller, Powers-Jones explores the use of the personal narrative as a means of engaging visitors on an emotional level with those who witnessed historic events.

While these chapters represent individual responses to specific challenges or areas of interest, there is sufficient complementary evidence to suggest that museums are becoming more astute, intuitive and capable of successfully using emotion as a means of engaging visitors within their spaces. But it is not solely within the physical spaces of the museum that emotional responses are being courted.

Explosive growth in the use of social media and the recent proliferation in mobile ‘smart’ technologies, while undoubtedly falling short of transforming democracy itself, is at least revolutionising communication, making information infinitely more accessible and redefining personal relationships on many levels. While the initial fear was that museums would lose control of their authoritative voice, there has instead been a collapse in the distance between expert and audience and the emergence of a global community who want to interact with museum experts in ways that reinforce, even as they re-negotiate, that authority in the museum.

Through such media, groups and individuals are finding new ways of defining themselves in relation to object heritage, of using collections to tell stories, to curate their own archives and construct their identities. In so doing, they are not only involved in a creative exploration of notions of authenticity as they relate to the museum, but they are also creating and participating in a variety of experience.

This brief foray into the online space is a useful reminder that museums do not exist in isolation. They are now part of a consumer industry and a leisure society in which emotion, not particular products or services, is currency. This trend, although not new, has now achieved hyper-real ubiquity. I see this daily in my work at the Tower of London, where both formal and informal learners arrive fully expectant of ‘experience’: emotional, immersive and engaging. Indeed, those learning programmes that deliver the deepest transformational outcomes do so precisely because the audience’s learning journey is specifically designed to be an immersive, emotive and purposeful ‘experience’.

At the time of writing, an economic depression has enveloped much of the globe. This has had a significant impact on museums through the withdrawal of public funding, and, while this is a significant economic challenge, it also highlights a political challenge – how do museums position themselves to maintain innovation and relevance? The immediate response has been to institute cutbacks, often retrenching education and outreach programmes, and focusing on income generation. This generally means squeezing more out of the same audiences: cafes and shops become less an afterthought and more a destination, while a clear emphasis on delivering blockbuster exhibitions has emerged (for those that can). In this climate, audience-engagement work risks becoming again a marginal activity in the museum. In light of this assertion, it might be pertinent to be more wary of seeking emotional responses than ever. If we are not confident that we have the capacity for reflexivity, ethics, responsiveness and above all clarity in our agenda as we work with emotion and ask people to ‘feel’, then perhaps there are serious questions to be asked about the purpose of the museum.

References

Benjamin, W. 1936. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, trans. J.A. Underwood. London: Penguin [2008].

Bennett, T. 1995. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. London: Routledge.

Hooper-Greenhill, E. 2007. Museums and Education: Purpose, Pedagogy, Performance. Abingdon: Routledge.

Chapter 1

The Emotional Museum:

The Case of National Museums Liverpool

A few years ago I made my first visit to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC. As I ascended in the elevator to reach the displays, I found myself in the company of a group of teenagers, of both sexes, laughing and making a lot of noise. I could do with getting away from this lot, I thought, as I am on something of a pilgrimage, and the last thing I need is a gang of giggling teenagers distracting me from the serious business of studying the Holocaust. As soon as the elevator door opened, I shot off ahead, leaving the teenagers behind. Half an hour later, I encountered them again. This time they weren’t giggling. In fact, they seemed almost to be in a state of shock. Welcome to the emotional museum.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum is a social history museum, and it might be argued that all social history museums are challenging and emotional (or at least they ought to be), because they deal in human experience, in human behaviours. As a result, it might be said that visitors more readily feel an emotional attachment than they might in an art museum or a science museum or a natural history museum.

Julian Spalding wrote in The Poetic Museum, echoing museum traditionalists the world over, that collections are at the heart of museums (2002), but I believe that at the heart of social history museums are emotions – pride, anger, joy, shame, sorrow. Emotions which arise from an epic range of stories. Social history museums are about people not objects, and people are about emotions, not things. It is the contention of this chapter that emotions lie deeper within the museum psyche than collections.

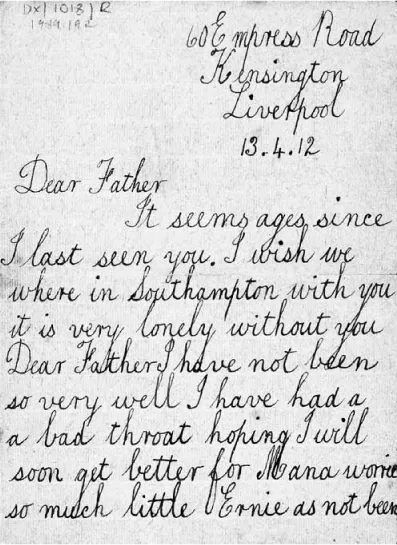

Another example: Birkenhead-born William McMurray, aged 43, lived with his wife and three young children at 60 Empress Road, Kensington, Liverpool. On 13 April 1912, his 10-year-old daughter, May Louise, sat down to pen her first-ever letter, to her father, who, like many Liverpudlians, worked away at sea and was often absent for long periods. This time, William McMurray had been away in Belfast for several weeks before taking up his job as a first class bedroom steward on a magnificent new White Star liner.

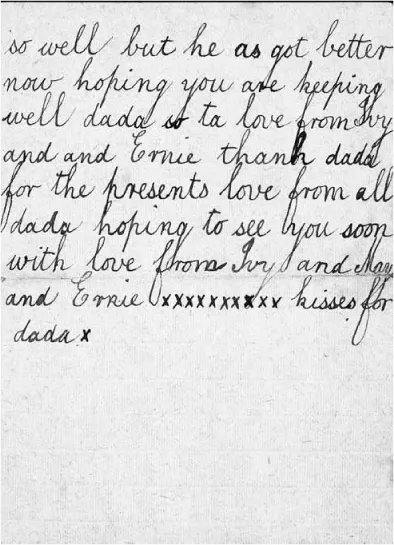

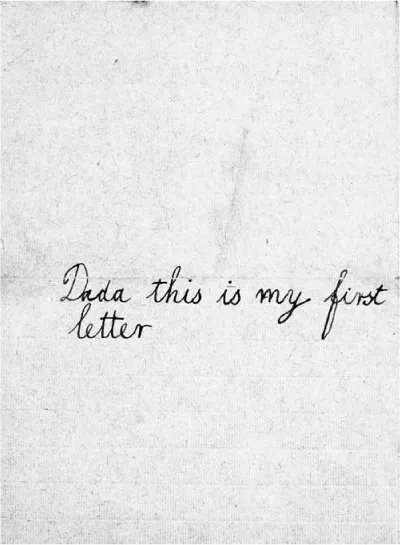

May Louise wrote, in her best handwriting (Figure 1.1):

Figure 1.1 Letter sent by May Louise McMurray to her father William McMurray, 1912

Source: National Museums Liverpool.

[Dear Father

It seems ages since I last seen you. I wish we where in Southampton with you it is very lonely without you Dear Father I have not been very well I have had a bad throat hoping I will soon get better for Mama worries so much little Ernie as not been so well but he as got better now hoping you are keeping well dada so ta love from Ivy and and Ernie thank dada for the presents love from all dada hoping to see you soon with love from Ivy and May and Ernie xxxxxxxxxx kisses for dada x

Dada this is my first letter.]

McMurray never received the letter from May Louise, because it arrived in Southampton after his brand new ship had sailed, bound for New York. Two days later he was one of more than 1,500 passengers and crew who died in the Titanic disaster. On 17 April, the date of her wedding anniversary, William’s wife received the shattering news of the loss of her husband. May Louise’s letter to her father was returned to Liverpool and treasured for many years by her family. It was donated to Merseyside Maritime Museum in 1989 by her own daughter. The letter is now on show in the museum.

There is no doubt that May Louise’s letter is an important piece of evidence. But it is its emotional impact that is its true value: the way in which it helps us get inside the minds of the people concerned. This is not just a letter, it is the only letter ever written to her father by a young girl, who only a few days later learned of his death. It speaks to us about family, love, childhood and loss. The letter breathes life – it breathes emotion – into what has become a historical narrative: the sinking of the Titanic.

Here, we touch upon a fundamental issue about museums, which is their very role in society – why we have them, why we fund them, indeed how we run them. We need to consider what we, the people who run museums, think we are here to do.

Museums have to connect with and have an impact upon the public. If they do not do that, there is not much point in having the museum in the first place. This may seem obvious, but if so, it does not explain why most UK museums still do not appeal to most people.1 I want to consider the mission and values of my museum service, National Museums Liverpool (NML) in the UK.

Our mission statement reads: ‘To change lives and enable millions of people, from all backgrounds, to engage with our world-class museums’ (NML 2012). Our values include the following statements:

• We believe that museums are fundamentally educational in purpose.

• We believe that museums are places for ideas and dialogue that use collections to inspire people.

• We are a democratic museum service and we believe in the concept of social justice: we are funded by the whole of the public and in return we strive to provide an excellent service to the whole of the public.

• We believe in the power of museums to help promote good and active citizenship, and to act as agents of social change. (NML 2012)

We acknowledge that museums can change people, and the underlying premise is that it is what museums do to people, their impact, that is important. Giving access to ideas and provoking an emotional response is, arguably, the most important function of museums – and this can be applied to all types of museum not just those concerned with social history.

Let us look at some other examples of emotion in the museum, continuing in Liverpool. In 2003, at Merseyside Maritime Museum, we created an exhibition on the Liverpool Blitz. The Maritime Museum was in those days rather a dispassionate place, with an emphasis on the technology of shipping and the maritime industries, which some liked, but which caused many never to go near the place. It had the distinction of losing visitors even after free admission was introduced for the first time in 2002. As the new director of NML, I noticed that the museum did not have a special exhibitions space and suggested to our maritime staff that they might like to have one. They bit my hand off and told me that because so few people ever visited the old ship model displays, they wou...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Contributors

- Introduction: Challenging History in the Museum Jenny Kidd

- PART 1: THE EMOTIONAL MUSEUM Alex Drago

- PART 2: CHALLENGING COLLABORATIONS Amy Ryall

- PART 3: ETHICS, OWNERSHIP AND IDENTITY Miranda Stearn

- PART 4: ‘TEACHING’ CHALLENGING HISTORY Samantha Cairns

- Index